The following pair of texts, as a fictional juxtaposition of viewpoints, is directly related to two presentations/discussions organized by the game over assembly during the winter and early summer of ’14: nature as ideology (January 29, ’14, at the Physics department) and science and metaphysics (July 7, ’14, at MITHI).

The first text consists of selected excerpts from the book The Phantom of the Opera, by Gaston Leroux, (University of Crete Press – 2014).

As is generally the case with such fantastical confrontations in the spirit environment, so too here, the purpose is not to diminish the value of that which is being opposed in the eyes of those who hold the opposing view. Nor is it to distort the meaning of their opinion (the selection of excerpts always carries such a risk). Mainly, we “take occasion.” We take occasion for counterarguments that are now considered demode.

one side

… Let us turn to the present day to ask ourselves … what is the position of science in societies that emerged as a result … of the scientific revolution that began with Galileo and was completed with Darwin. To what extent is the modern person’s worldview shaped by the scientific approach to nature and, furthermore, to what extent has the scientific mindset – the one that gives precedence to facts over our opinions and beliefs (political, religious, ideological or others) – become an organic part of the general culture of citizens. Unfortunately, empirical data leaves little room for illusions: irrationality and belief in paranormal phenomena constitute a “majority current” among the general population. One of the many polls conducted from time to time in the United States yields chilling results on this matter. The percentages of the population that believe in the strangest things are – for a few indicative cases – as follows: personal psychic experience 71%, belief in ghosts 34%, ghosts are souls of the dead 56%, haunted houses 37%, telepathy 31%, influence of stars on our lives 32%, extrasensory perception 41%, communication with the dead 35%, etc. etc. And so that we are not lulled by the idea that all this happens only elsewhere, a recent pan-European opinion poll conducted on the occasion of the Darwin year showed that we are second only to the United States in terms of rejecting our evolutionary origins. Darwin has no significantly more friends in Greece than in the U.S.!

The dominance of irrationality and pseudoscience in the public sphere is also undeniable, as evidenced by the widespread popularity of related television programs and a plethora of similar publications of all kinds, which together constitute a parallel world that “official society” simply refuses to acknowledge. It is one of its dark sides.

We are therefore facing a massive failure of our educational system to fulfill its educational mission. In an era of supposed triumph of science – or perhaps only of technology? – a constantly increasing number of citizens emerge from the educational system ready to surrender without resistance to the most extreme forms of irrationalism…

… Defending science today – not just its achievements but also its methodological core – is not particularly “fashionable.” It risks being characterized as a soldier of the past war. A remnant of another era. A supporter of the Enlightenment, for example: an outdated idealist! I am not a historian of science or ideas to attempt a documented interpretation of this phenomenon. How, that is, did the value sign of science change so much and so quickly – mainly over the last fifty years? From positive to negative, or at least neutral. From a liberating force and fundamental component of our civilization to being viewed by most as merely a driving force of technological progress that – as many believe – no longer serves genuine human needs but rather the unchecked expansion of a globalized economic system that sedates the very future of the planet as the cradle of life.

Under these new conditions, it is not surprising that some of science’s traditional enemies—religion and extreme conservatism—have been joined by former allies. Among them is a segment of academic thought. I am not, of course, referring to critical stances or radical questioning of technological innovations and the lifestyles and forms of social organization that these promote and ultimately impose. I mean the questioning of science itself at its epistemological core: the fundamental assumption that the scientific method—that which prioritizes empirical and experimental data over our theoretical constructions—is a valid source of knowledge about our world. That it provides objective knowledge of a cumulative nature. New knowledge does not invalidate the old, but extends its boundaries and redefines the conditions of its validity.

In the name of a strict epistemological approach to the problem of valid knowledge, this type of critique directly challenges the decisive role of experiment as an external arbiter of theory and as a guide for formulating increasingly better theoretical models to describe the natural world. Experiment — such a critique claims — is permeated by the terms of the theory to be verified, and therefore does not constitute a truly independent test of it. In its most extreme version, this critique practically claims that the game of verification is “rigged.” Experiment “sees” only what theory allows it to “see.” The claim of “Western science” to be considered objective, and therefore superior to other forms of science, is unfounded. Our science — Western science — is simply one of the many equivalent sciences created by human cultures to “familiarize” themselves with the world around them. Ultimately, “everything is relative.”

The project is well-known and worn out. Another “deconstruction” from the safe ones. Because, of course, none of the deconstructors turn to the “tribal magician” for medical help, but to doctors and medical technologies that rather rely on this “damned” western science!

…

In my opinion, there is no doubt that we are witnessing a massive retreat of science and the scientific mindset as a fundamental component of citizens’ general education…. In an era of supposed triumph of science, a steadily growing number of people are emerging from the educational system ready to surrender without resistance to the most extreme forms of irrationalism and pseudoscience. Easy prey for related television programs as well as a plethora of similar publications of all kinds that constitute on their own a parallel “universe” of mystery and madness. Which the “official society” simply refuses to acknowledge. Or pretends not to see. It is one of its rejected aspects.

However, this is certainly not solely the fault of… detractors or traditional enemies of science. A large part of the responsibility also lies with a significant “mutation” that has emerged within the scientific community—mainly in the natural sciences—over the past fifty years. Initially imperceptible, but later accelerating at a rapid pace. This refers to the emergence—and eventual dominance—of a new type of scientist: highly specialized and efficient in performing specific “duties,” yet often devoid of any broader education, even within the immediate scope of their own field. The non-intellectual scientist. The technician of science. This is now the predominant type of person representing the scientific profession and its dominant ideology. This ideology certainly includes many new things—among others, concepts such as innovation, entrepreneurship, spin-offs, patents, European programs, etc.—but only a vague notion of science as a fundamental value of our civilization. Of science as an intellectual good and as a liberating force for humanity, as envisioned by the Enlightenment and the great intellectual tradition it created. The enemies of science—old and new—are certainly somewhat to blame; however, if science today is retreating as an intellectual movement, the responsibility lies equally both within and outside of it.

…

the other side

Is there something that can be precisely defined as science, transcending the various historical (or social) determinations of the last 5 or 10 centuries of “Western” history? Historians of science themselves seem to answer “yes,” defining the line of distinction between “science” and “non-science” (whatever that latter might be) in relation to method rather than to conclusions, their applications, their successes and failures, inconsistencies, or the duration of validity of the “truth” of this or that scientific theorem. However, such a definition (of the sort “science is experiment plus mathematics”) is highly debatable. Especially if one happens to witness fierce disagreements and arguments among “scientists” — someone who does not hold that supposedly sacred title. In such cases, the category of “anti-scientific” is the mildest label that can be hurled among them; which means, at the very least, that what constitutes “science” remains relative even among those who claim to serve it.

As if these were not enough, and to make things even worse, the distinction between “science” and “technology” has almost disappeared. There are certainly strong connections between them, and there always have been. But as “technology” (or, more accurately, certain fields within it) continuously produces more and more machines/devices for everyday use, shaping what some have called a technological ecosystem, it also constructs and adopts representations of the “general public”; ideology, more accurately.

For technology, the prevailing idea is practical. It works: machines “work” (or break down). For science, the prevailing idea is much more philosophical. It is the truth. The “truth of the world,” to a sufficient (though not always acknowledged) degree the “immutable truth of how things ‘are’ (that is, how they ‘function’).” Although many (including Mr. Trachanas among them…) claim that the defining element of anything that can be called science is experimentation (along with the verification or refutation of a given hypothesis or theory), in our view the main characteristic is something else. It is the secularization of the “laws (of nature).” That is, the ability of the human mind to conceive/understand/analyze/translate them, as opposed to the religious notion that such “laws” do exist (and indeed very strict ones), but that they are known only to some god, and thus inaccessible to human understanding.

The commonplace idea, then, of natural law (from the “law of gravity” to…) and therefore of the inherent Truth (with a capital “T”) of every natural law, which is or can be understood by a small subset of this “nature” (the human species…), an idea that constitutes a secularization of another, the idea of the “world-creating god” and sole knower of the “laws,” is what inspires but also haunts scientists. At the heart of any scientific inquiry, theory, or method lies the ghost of a great clockwork mechanism; it matters not whether the gears have been sought in Mendel’s “laws of heredity,” Kepler’s “laws,” the “laws of quantum mechanics” in the Copenhagen interpretation, or now in the “laws of quantum entanglement.”

We are therefore entitled to raise the following question: if any “body of knowledge” defines its own ways, its own “internal rules,” its own “internal processes of verification or/and falsification,” is it automatically entitled to be immune to any external criticism? Christian religious faith claimed, at its best, to constitute the only valid form of knowledge, let us say “knowledge through revelation.” It had shaped not only the “internal rules” of the “path toward divine illumination,” but also institutions/mechanisms of “verification or/and falsification”: for example, episcopal synods (a kind of councils…) where heretics were often anathematized – that is, the “false believers,” the “deceived,” the “instruments of Satan.” Certainly, experimentation was not generally included in the repertoire of seeking divine illumination; but this did not make the church hierarchy less certain that it knew or was close to the “divine will” or the divine order of the world.

However (and the history of science is witness) even experimental scientists (various, indeed, particularly famous ones) lived and died with the certainty that they knew at least one of the fundamental – laws – of – nature; only for a later (initially “heretical”) new scientific truth to come and contradict them. Until it too is contradicted by a subsequent one.

As a collective adventure of human thought, these successive waves of discovering “laws of nature” and then disproving them—which characterize whatever might be called science—are particularly fascinating, even entertaining, up to a certain point at least. When it comes to the oath concerning the revelation of Truth, of immutable and unquestionable Truth-of-the-World, science is a collection of failures, no less than various religious collections. And perhaps here lies a pure (albeit unacknowledged) reason why, from a certain point in time onward (let’s say: in the wake of the twentieth century), even “learned scientists” become increasingly openly metaphysical, often of the worst kind. There probably exists a fundamental (intellectual) error in the belief (for it is indeed about belief) in the existence of a single, immutable, and unquestionable Truth (with a capital “T”) regarding the World. And if this is the case, this mistake is equally shared by scientists and theologians; which means they might be closer to each other than they themselves acknowledge. In the end, scientists are no longer justified by the joy of adventurous thinking, but by the applications they produce. By technology, that is.

After these brief and general remarks (there will also be some general thoughts at the end), let us turn to our specific subject. Mr. Trachanas, on page 22 of “the phantom of the opera,” writes:

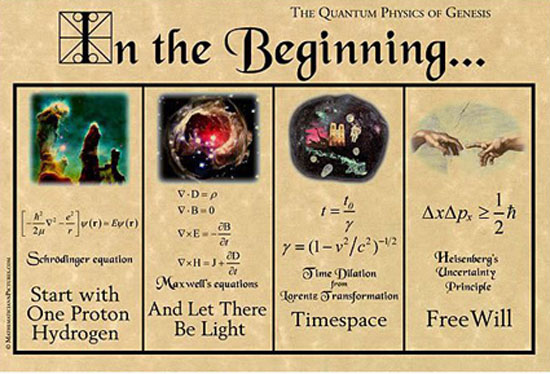

… I will attempt to defend … a fundamental scientific discovery that belongs to my own science, physics. I will attempt … to show why this discovery constitutes a supreme achievement of our civilization, worthy of inclusion in the short list of general education topics about which a cultured citizen of our time should know something. This concerns the famous Heisenberg uncertainty principle, or uncertainty principle, as it is also called, which was discovered in 1927 and has since constituted the foundation of microcosmic physics.

… If the uncertainty principle deserves to be included in the short list I mentioned earlier, it is mainly for this reason: without this strange physical law – because it truly is a strange law – none of the fundamental conditions that make the emergence of life in the universe possible would be present. A universe without the uncertainty principle would certainly be a dead universe…

One could think that the universe – began – to – live only after 1927, when the German physicist Werner Heisenberg formulated what he called uncertainty principle… Not at all! The universe seems to manage just fine without Heisenberg, Bohr, Schrodinger, L. de Broglie, Planck and several other physicists who from the early 20th century began formulating theorems, hypotheses and possible “laws” around a completely novel (for the then known data) idea about the state of matter (and energy): the idea of quanta.

According, therefore, to Heisenberg the uncertainty principle consists in the belief that:

It is impossible to simultaneously and accurately measure, neither practically nor theoretically, the position and velocity, or momentum, of a particle.

[In contrast] to the principle of causality, according to the principle of uncertainty there are events whose manifestation is not dictated by any cause.

If the principle of uncertainty has a particular (social in general but also specifically scientific) value, it is not, therefore, because it gave breath to the universe. But because (in combination with other aspects of quantum physics) it overturned (and perhaps destroyed forever) the fundamental intellectual ground upon which the tower of scientific pursuit of Truth had been built until then. And this ground condenses, on the one hand, into the basic position that either this is true, or it is false – there are no (for science) intermediate states, “a little correct / a little wrong”; and on the other hand, into rigid determinism, into the direct correlation of result and cause.

Here then, on the eve of that historical period which “many people” would later remember as the era of the Great Depression (and subsequently of fascism and the Second World War), behold how the emergence of a new scientific paradigm, quantum mechanics, was silently overturning (albeit temporarily and within a relatively limited field of physics…) the fundamental certainties upon which the hitherto scientific epic had rested, in its entirety and as a whole: the certainties concerning a definitive (cosmic) Truth.

Here is what Heisenberg himself said in his work Physics and Philosophy (from Anagnostidis edition, 1971) somewhere in the 1950s. The emphasis is ours:

…

In classical thermodynamics, the concept “temperature” appears to describe an objective characteristic of reality, an objective property of matter. In everyday life, it is very easy to define, with the help of a thermometer, what we mean when we declare that a piece of matter is at a certain temperature. But when we try to define what is meant by the temperature of an atom, we find ourselves in a much more subtle situation, even in classical physics. Indeed, it is impossible for us to associate this concept of “temperature of the atom” with a well-defined property of the atom… We can associate the temperature value with certain statistical probabilities regarding the properties of the atom, but it seems questionable whether such a probability should be characterized as objective.

…

In quantum theory, all classical concepts… are linked to statistical probabilities; and this probability can rarely be equivalent to certainty. It is difficult to claim that a probability is objective. We could perhaps characterize it as a tendency or objective possibility, potentia, in the sense of Aristotelian philosophy. Indeed, I believe that the language used by physicists when speaking about atomic phenomena implies in their minds concepts analogous to the concept of potentia. Thus, physicists gradually begin to consider electronic orbits, etc., not as reality, but as a kind of potentia. The language has already adapted (at least to a certain extent) to this actual state of affairs. But this is not a precise language with which we can employ logical schemes; it is a language that creates images in our minds, along with the notion that these images have only an indefinite relationship to reality, that they… They do not represent anything but a tendency towards reality.The ambiguity of this language, which physicists use, led therefore to attempts to define another precise language, in full agreement with the mathematical framework of quantum theory.The result of these efforts by Birkhoff and Neumann, and more recently by Weizsäcker, can be expressed by saying that the mathematical framework of quantum theory can be interpreted as an extension or modification of classical logic. There is particularly one basic principle of classical logic, which seems to need modificationIn classical logic, when a proposition has even the slightest meaning, it is assumed that either it or its negation must be true. Between the propositions “there is a table here” or “there is no table here,” either one or the other must be true: there is no third possibility, this is the logic of the “excluded middle” or “tertium non datur.” It is possible to ignore which of the two is true, but in “reality” only one of the two is such.

In quantum theory, we must modify this logical law of “excluded middle.”.

…

The strong modification of the schema of classical logic would then be applied primarily at the level concerning objects.

Let us consider an atom displaced inside a closed box, which is divided by a partition into two parts, while the partition has a small hole through which the atom can pass. In this case, according to classical logic, the atom is either in the left half or the right half of the box, there is no third possibility, there is an “excluded middle”. But in quantum theory we are forced to accept – when we use the words “atom” and “box” – that other possibilities exist, which are paradoxical mixtures of the two previous possibilities; this is necessary for us to understand the results of our experiments.

…

To understand this situation, Weizsacker introduced the concept of “degree of truth”… [This degree, as a “value”, can be 1 or 0, but it can also have intermediate values]… However, the applications of such a language raise a considerable number of difficult problems, among which are the relationship between the various “levels” of language [one for empirical observation, another for quantum mechanics] and the consequences of the implied ontology…

Truths – conditionally – in place of Truth; probabilities in place of certainty; more “intermediate” (or “complementary”) states of matter beyond the either it exists – or it does not: certainly the quantum physicists managed to synthesize these into a new scientific Truth… However, what a reversal, eh? The according to Heisenberg implied ontology (illuminated by science) was coming upside down, not yet in the eyes of the public, but…

And Heisenberg had the determination to demonstrate this reversal even more intensely. In the final chapter of Physics and Philosophy, titled The role of modern physics in the contemporary evolution of human thought, writes among other things (the emphasis is ours):

…

The general trend of human thought in the 19th century was the increasing trust in the scientific method and precise logical terms, leading to a general skepticism towards those concepts of ordinary language that do not fit into the closed framework of scientific thinking, such as religious concepts. Modern physics greatly reinforced this skepticism; but at the same time, it applied this skepticism by overestimating scientific concepts, clear and precise, with a very optimistic view of progress in general…

…

But… The spiritual openness of modern physics can, at some point, help reconcile ancient traditions and new currents of thought. For instance, the significant contribution that came from Japan to quantum theory since the last war may be an indication of a certain affinity between the traditional philosophical ideas of the Far East and the philosophical content of quantum theory. It is possible that it might be easier for them to adapt to the quantum concept of reality, having not gone through the mindset of naive materialism that still prevailed in Europe during the first decades of our century. We certainly will not consider these observations as an undervaluation of evil, which may have occurred or has occurred in ancient cultural traditions from the fires of technical progress. But since all this evolution has long escaped the control of human forces, we must accept it as one of the most essential characteristics of our time and we must connect it as much as possible with human values, which were the purpose in ancient cultural and religious traditions.

…

Having still very recently witnessed the incredibly criminal test of this weapon called the “atomic bomb” (for the development of which Heisenberg himself worked, during the Second World War, in the research centers of the Third Reich…), all quantum physicists could wonder, there in the middle of the 20th century, about whether there are (and what are) the moral limits of science… Hence also the appeal to “religious traditions,” a strange invocation otherwise to the old enemy of scientific rationalism.

However, the overturning of certainty regarding the existence of “objective Truth” and the (somewhat later) acknowledgment that the observer influences what is observed (meaning that the experiment had by now fallen far below the noble summit of hard objectivity), products of scientific theories and not of any irrational (or anti-rational) restoration, were undermining from within those things which Heisenberg could indeed, in retrospect, characterize as “naive materialism,” but which had historically constituted the foundation not only of physics but of scientific knowledge in general.

Demosthenis Dagklis, physicist, professor and philosopher of science, in an interview with “Efimerida ton Syntakton” on September 13/14, 2014, was asked and answered on the subject:

QuestionNearly a century has passed since the so-called “orthodox” or “dominant” quantum interpretation of the microscopic world was formulated in Physics. Since then, tons of ink have been spilled to formulate partial criticisms, radical oppositions, or even “alternative” theories. In your opinion, why does the gap between the classical and quantum interpretation of nature remain unbridgeable?

AnswerIt is known that, regarding the concept of “objectivity,” quantum theory brought about a much greater rupture with the past, namely Classical Physics, than Relativity did.

It introduced randomness as the dominant characteristic element of the natural microcosm. It fully adopted the positivistic-empirical criterion of existence, namely “only what is observed exists.” It is also now considered that experimental conditions constitute a component of the “given,” making it impossible to distinguish the objective in its old meaning.

In other words, the objective is considered to be “realized” through observation – experiment. However, many reacted and continue to react to these radical epistemological changes…

However, the main problem is not so much the ontological assumption of the dominance of randomness in the microcosm or the empirical criterion of existence, but rather the direct consequences that arise from the combination of these two within the formalism of quantum theory.

In more “technical” terms, this refers to the “irreversibility” observed in experimental measurements, for which a “responsible” cause needs to be sought (given that the fundamental equation of the theory, namely Schrödinger’s wave function, expresses a classical, that is, reversible, deterministic, and continuous evolution).

If we exclude other proposed solutions (e.g., hidden parameters, Everett’s many worlds, which however are not currently favored), the responsible party that remains and emerges as the favorite is the cognitive subject itself, that is, the observer as “mind” or as “consciousness.” Some, like the renowned theoretical physicist Eugene Wigner (E. Wigner), initially considered this version more “respectable.” However, from this position to… “the embrace of Bishop Berkeley,” the step is almost negligible.

…

The last question and answer of the interview is also provocative. Our emphasis:

QuestionThe dynamics of modern science present an unprecedented “freedom”: it generates the most fantastic and counterintuitive objects, conceived precisely to satisfy purely theoretical needs. How legitimate—philosophically or methodologically—do you consider this modern scientific freedom to be?

AnswerYou are right. In our era, research into the microscopic world, always combined of course with the corresponding research in the field of Cosmology, has created an explosive situation regarding the hyperproduction of fantastic and bizarre theoretical inventions.

Terms such as “non-locality and superluminal speeds”, “teleological construction of the world”, “parallel universes”, “holographic universe”, “teleportation” and many others continuously ignite the imagination.

We live, we would say, in an era of scientific-theoretical “anything goes” (everything is permitted), always within the “kingdom of the violently disconnected.” An era completely opposite to that of the “conservative” Poincaré, for example, who, when he discovered – first of all – discontinuous functions, rejected them, characterizing them as “monsters.”

We should not, however, overlook a common characteristic that increasingly appears today with a growing tendency toward dominance. This refers to the persistent presence and strengthening of “idealism” in its various forms, as opposed to “materialism.” The well-known opposing pair that some now consider… outdated.

We readily acknowledge, of course, that even these opposing terms are not exempt from the broader historical evolution of human ideas. However, even if we adopt Engels’ suggestion that every major scientific discovery necessitates a modification of our understanding of “materialism,” this certainly does not imply the subordination of the latter to “idealism,” which usually constitutes “disguised spiritualism.”

Perhaps again, with reference to quantum theory, the modern distinction between “object” and “subject” might close its historical circle. The enormous significance of such a possible development is obvious and has been explored by many philosophers (starting with Nietzsche), but it is not within the scope of the present text to comment on it; surely, however, it reinforces the skeptical tendency of the “objections” to the dominant quantum mechanical interpretation.

It is therefore certain and by no means far-fetched to say that for several decades now, in ways invisible to the vast majority of capitalist societies, what has historically been called “science” has been experiencing extremely powerful upheavals—as neutrally as possible. And although it is easy to focus on the “ontological” consequences of these upheavals, in the name of clarifying such and such scientific theories (in a kind of internal dialogue or even war among scientists…), it is precisely these “ontological” consequences that inevitably spill over from the “scientific body” into whatever social environment. And this is so as long as the “scientific body” is nourished by its social environment. Consequently, it discharges into it even the “unpleasant residues” of its operations.

For centuries, science has cast aside the distant divine wisdom from its throne, promising not some worldly vagueness nor the gamble of daily life, but certainties—accessible to human observation and/or human thought. Science sidelined religious faith, promising not the relativity of truths, but Truths (with a capital “T”), provable again and again through practical, experimental means. Such were the terms by which scientists of the bourgeois class took the helm of ideologies for social use; such were the terms by which not only the disenchantment of the world but, above all, the creative liberation and enlightenment of human thought was attempted. Could this situation have officially, openly, and honestly changed at some point during the 20th century? Would it have been possible for scientists to step forward and repeatedly declare that what is considered certain (from a material perspective) consists of exceptions within an infinite uncertainty and, perhaps, mere illusions; that the world (and our species) consists of infinitesimally small particles existing probabilistically in one state or another; and that the only certain scientific knowledge is the recognition of scientific ignorance? To put it schematically: would it be possible to reconstruct “science as a spiritual movement” supporting a life (individual and social) with probabilities? And, on the other hand, capitalist societies could (and which, pray, subjects within themselves?) to adopt happily, liberatingly (we would dare to say: poetically in the literal sense of the word) a strong principle of uncertainty in individual and collective life?

It seems that scientists are trying to keep their demons as far away as possible from public knowledge. And their motives are self-serving. If the epistemological demons were recognized by “non-scientists,” then the renowned “scientific community” would risk losing, for an unknown transitional period, its special status, its respected hierarchy (and its generally high incomes); a status, hierarchies and incomes that were shaped in times of ironclad certainties. The cages of the demons aim to hide the (relativistic) anything goes behind the (absolute) all is well. One of these is technology and its applications: as long as these work (with whatever mysterious, even metaphysical, characteristics this “working” entails), then “all is well.” Another cage is the still prevailing educational system. This historical (urban/capitalist) epistemological process, which was the primary method of familiarizing/adopting the “scientific spirit” (its fundamental assumptions at early educational stages), maintained, in the form of “teachable material,” the heroic certainty of natural (and mathematical) Truths, simply doing propaganda. And leaving (the educational system) its victims to realize later, at a more mature age, if they show persistence, dedication, and endurance, that they have been epistemologically deceived: one and one do not necessarily make two! (However, one and one do indeed make two when it comes to thousand-euro bills…)

If, indeed, quantum theory (having acquired, as quantum mechanics, some extensive field of applications accessible to everyday life) is destined in the future to put the final nail in the coffin of the modern distinction between subject and object, then a certain ontological (ultimately social) restructuring, already underway for several decades, will have been completed, backed by a powerful theory. With consequences that we cannot calculate at this moment. The “transcendence of the subject-object distinction,” as it operates within commodity fetishism—as the realization of human relations in objects (including devices/machines)—will, first of all, be accomplished. Also (for the general public), the mythologization/re-enchantment of tools will be completed. Then, social irrationality will become invisible, since it will be overcome by the technical rationality of (including quantum) machines. In many ways, indeed, this is already happening, even without quantum applications.

Let’s recap. The capital utilization has become extremely dynamic, innovative and flexible, in a historically unprecedented manner over the past 4 or 5 decades. Both its dynamism and flexibility, as well as its metaphysical investment, have stemmed directly from the sciences, including the so-called “social” sciences; and the continuous search for applications of one theory or another. Science, speaking generally, has long ceased to be something like an intellectual appendage of biases and misanthropy. And this development is not the fault of the “deconstructionists” (even the use of this word refers to ideological evaluation, which is incompatible with “scientificity”…).

The opposite is rather true: there are quite a few who have identified not only the paradigm shifts within the body (bodies) of scientific truths, but also the general paradigm shift of science as such: of sciences not only as producers of “truths” with relative value, but also, primarily, of sciences as intentionalities at the outset of producing whatever “truths.” Only such an identification belongs much less to the realm of science and much more to that of political critique.

Of course, it is extremely telling that large segments of prehistoric societies believed in ghosts, in the influence of the stars on their lives, or in the virginity of the Mother of God. But the dynamic element of those same societies are those who believe in “enter,” “delete,” and “search”; in the immaculate conception of wealth; in “immaterial” labor and “immaterial” capitalism. Faced with these developments, the defense of science (of physics…) of the era of Galileo and of the radical, for social use, spirit of the Enlightenment, becomes sheer obituary.

Ziggy Stardust