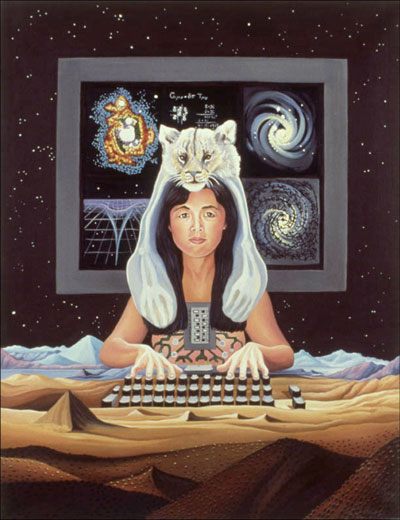

Cyborgs are ether, the quintessence

We are now traversing the sixth decade since the writings of Manfred Clynes and Nathan Kline gave substance to the cyborg construct/artifact. Today, although it has been somewhat undermined by more fantastical imagery, such as that of the digital self, it continues to exhibit remarkable vitality. This is undoubtedly due to the dual nature of technology; it is simultaneously technical and ideology. And while it is with the former form that it provides the most solid, imposing, but also terrifying examples—such as a combat drone that kills dozens of defenseless people controlled from thousands of kilometers away—it does not cease to produce equally cohesive results with the latter, without even needing reference to any tangible version.

The cyborg is a characteristic such case. For half a century now it has been circulating among us like a ghost that intervenes in behaviors, mindsets, social relations and worldviews, to the point of being more real and effective than an army of chemically doped mercenaries in Baghdad. And while many of the technical or/and ideological products of new technologies are met with justified repulsion, the cyborg is among those that inspire fear if not fascination. One reason this happens is because the cyborg has a dual origin. The one and obvious is the laboratories of the military-industrial complex, and if it were the only one then the cyborg would only retain its repellent aspect. But the second is the postmodern left-wing thought which, seeking new meanings and interpretations for a world that -according to its opinion- the class war has ended, if it ever existed, class analysis has gone bankrupt and the proletariat has disappeared, discovered in the cyborg the vehicle of a new post-capitalist “narrative”. Thus the cyborg was politicized in the left’s universe not as a negative force, a technical representation of the enemy, but as a promise of unlimited possibilities and a potential agent of empowerment and liberation. In the following lines we will try to find out how this began, that is, how the cyborg became an argument against class analysis.

We are all cyborgs (;)

The beginning of the 1980s was a difficult period for movements, a time of large-scale rearrangements. The great counter-offensive of the bosses had already begun, and the movements, after an exceptional period of inflationary explosion of denials and competition, had found themselves in a position of retreat, if not decomposition. In the USA, “Reaganism” policies dominated (a brother model of “Thatcherism” on the other side of the Atlantic – the name derives from then-president Reagan), and among these, the “Star Wars,” the futuristic military doctrine then under formulation, was a matter of daily order.

Amid this context, in 1983 the American journal Socialist Review invited a series of socialist feminist women to submit their views on the future of the feminist movement in light of the decline of the left. Donna Haraway1, a well-known activist and intellectual of the socialist/marxist tendency of the feminist movement, responded to the call with a text that caused shock and awkward reactions. Its title was “A Cyborg Manifesto”2 and the journal refused to publish it for political reasons, deeming it extremely controversial, intellectualist and ultimately anti-feminist. It was eventually published two years later by another editorial team of the journal (and in 1991 in its final form in Haraway’s book “Simians, Cyborgs and Women”).

Already from the opening lines of the text, Haraway’s provocative and incendiary disposition is evident:

My ironic faith, my blasphemy, has at its center an image, the cyborg. […] At the end of the 20th century, in our times, mythical times, we are all chimeric constructs, theoretically and technologically crafted hybrids of machine and organism; in short, we are cyborgs. The cyborg is a condensed image of fantasy and material reality simultaneously, of the two articulated centers that structure every possibility of historical transformation.

Before we delve into the details, you should definitely keep the following in mind. The manifesto is the foundational act of birth of the political cyborg. If Clynes and Kline are the ones who shaped the mold of the “cybernetic organism” by mixing flesh and machines, it is Haraway with her manifesto who crafted the political and social characteristics of the cyborg, and for this reason, to this day it is considered an emblematic work in the relevant literature. It is the manifesto that took this construct out of NASA’s laboratories and first introduced it into the field of anti-institutions and social struggle. From Haraway in 1983, a thread begins that reaches until today, a thread that weaves together on one hand techno-fetishism and on the other hand the belief that technology, the change in the organic composition of capital, produces new revolutionary subjects and conceals possibilities for handling.3 Moreover, even if readers ultimately judge the manifesto to be now “old” and therefore of little need for critique, let us keep this in mind: the rhetoric that Haraway first developed is the same that, in one way or another, constantly returns and revives tirelessly over the last thirty years, sometimes with a more liberal and sometimes with a more anti-authoritarian approach, but always with the same purpose. To prove that the proletariat is now a disarticulated ghost of its former self.

Ode to the post-human

Being of Marxist descent, Haraway did not randomly use the concept of “manifesto” in the title of her text, directly referring to the communist manifesto, since her ambition was for the cyborg manifesto to play a similar role. “It is the fantasy of a feminist speaking in idioms that spread terror through the circuits of the new right’s redeemers” she proclaims as another – modern – ghost over the primordial dominion.

The text is convoluted—and this isn’t even a negative critique. Intellectualist, hyper-condensed, and symbolic, filled with many uninterpreted neologisms and even more assumptions, with minimal references to anything that might point to a fact or evidence, it serves as a written confirmation of the motto “now theory speaks!”, which at the time was very popular in academic circles. It addresses insiders of the postmodern theoretical idiom, despite the claim that it constitutes a tool for direct political action; the thematic focus and argumentation constantly sidestep, backtrack, and get lost; it’s not complex, it’s deliberately tangled and contradictory; ultimately, it might be better judged as poetry or prose, or even as metaphysical catechism full of naive oversimplifications, rather than as a political text.

In the immediate field of feminism, Haraway attempts to overturn two entrenched conditions that she believes are centrally responsible for the movement’s decline. One is the fragmentation and polydispersion of the feminist movement along competing identity lines, and the other is the deeply rooted notion that the female gender is grounded in nature, in contrast to the male, which is based in culture; both of these, combined with the fact that all previous “unities” and “identities” are obsolete:

It is now difficult to characterize feminist views with a single adjective—or even to insist on that name in every instance. The consciousness of exclusion through naming has become acute. Identities appear contradictory, partial, and strategic. Gender, race, and class, with the painfully won recognition of their social and historical construction, can no longer serve as the basis for believing in an “essential” unity. There is nothing in the “female” that naturally connects women to one another. There isn’t even the condition of “being” female, which is itself a highly complex category constructed through contested scientific discourses on sex and other social practices. Gender, racial, or class consciousness are achievements imposed upon us by the terrible historical experience of the contradictory social realities constituted by patriarchy, colonialism, and capitalism. And who, really, counts as “we” in my rhetoric? Which identities are made available to establish such a potent political myth called “we,” and what would the motives be for recruiting into this collectivity? The painful fragmentation among feminists (not to mention women) along every possible line of division has made the concept of woman elusive, a justification for the matrix of dominations exercised among women themselves.

These lines suffice to reveal some basic elements of Haraway’s rhetoric. Class, then, is one among other “identities,” our “class identity” has been “imposed” upon us by the “horrible” and “contradictory” experience of capitalism, and we must found a new “myth” for “us.” That is, the awareness that the class system is the heart of capitalism, which serves the organization of exploitation and the individual appropriation of collectively produced wealth, is an outdated consciousness, an “identity” burden that we should voluntarily shed, in order to free ourselves from this “horrible” reality.

Regarding the question of available identities suitable for a new myth, Haraway devises the cyborg4 and answers both issues in the same way. No, there is no separation or distinction among women, because we are all hybrids, artifacts, cyborgs; no, there is nothing natural in the feminine and no special bond with nature, because we are all cyborgs.

More revealing, however, is the reasoning according to which the cyborg emerges as a strong and compelling political proposal, capable of undermining radical and class-based analyses that are outdated, according to her. Thus, according to the author, the development of new technologies and sciences (primarily communication sciences and biologies) reached such a point in the late 20th century that a series of pivotal ruptures led to the disruption of deeply entrenched boundaries.

The first such rupture concerns the border between human and animal:

In scientific culture… the boundary between human and animal has been thoroughly breached. The last bastions of uniqueness have been contaminated, if not transformed into amusement parks: language, tool use, social behavior, mental events—none of these convincingly resolves the distinction between human and animal… The cyborg appears in myth precisely where the boundary between human and animal is transcended.

The second concerns the distinction between human and machine:

Machines before the cybernetic age could be decomposed; the shadow of the ghost hidden in the machine has always existed… The mere thought that machines were alien was paranoid. Now we no longer have the same certainty. Machines in the late 20th century completely blurred the distinction between the natural and the artificial, between mind and body, between self-development and external design, as well as between countless other distinctions that once applied to organisms and machines. Our machines have an annoying liveliness, and we have a terrifying inertia.

The third rupture concerns the distinction between material and immaterial:

The boundary between the material and the immaterial is very vague to us… Modern machines, in their quintessence, are microelectronic devices: they are everywhere and invisible. Modern mechanical equipment is an impudent upstart god, parodying the omnipresence and spirituality of the Father… Our best machines are made of sunlight; they are all light and clean, because they are nothing but signals, electromagnetic waves, fragments of a spectrum.

The result is to irreversibly destabilize all the frozen dualisms of civilizational reason (mind/body, matter/spirit, man/woman, nature/culture…) and to open the way for “polymorphous fusions” and “dangerous possibilities.” It is precisely through the gaps of violated boundaries, in this liminal zone, that the cyborg emerges. In Haraway’s epic, the cyborg has supernatural or non-natural dimensions (literally, according to its logic):

The cyborg is a creature of a post-gender world; it has no investment in the binary of sex, the pre-Oedipal symbiotic relationship, non-alienated labor, or any other seduction of organic unity.

[…]

The cyborg is committed absolutely to partiality, irony, intimacy, and perversity. It is oppositional, utopian, and completely without innocence. It is no longer structured by the polarization of public and private, and thus the cyborg defines a technological politics based partly on the revolution of social relations in the home. Nature and culture are reworked; nature can no longer be conceived as a resource to be appropriated or incorporated by culture. The relationships that form unities from parts, and among them the relationships of polarity and hierarchical dominance, are at stake in the cyborg world. Unlike what Dr. Frankenstein’s monster hoped for, the cyborg does not expect its father to save it by reconstructing the garden; that is, by constructing for it a heterosexual mate, leading it to fulfillment within a completed whole, a state, and a harmonious universe. The cyborg does not dream of community based on the model of the organic family, with the sole difference being the absence of the Oedipal complex this time. The cyborg would not even recognize the Garden of Eden; it is not made of clay and cannot dream of returning to dust. Perhaps that is why I want to see if cyborgs can subvert the apocalyptic doom of returning to nuclear dust, driven by the manic compulsion to name the Enemy. Cyborgs have no reverence; they do not reconstruct mnemonic members of cosmic harmony. They are troubled by holism, yet they seek connection—as if they inherently feel the tendency for a unifying front politics, but without a revolutionary vanguard party.

[…]

Humans have not come close to anything so fluid, as material and transparent. Cyborgs are ether, quintessence. These machine-belts of solar light are as deadly precisely because cyborgs are everywhere present and invisible. They are equally indistinct politically and materially. They have to do with consciousness—or the simulation of it. They are flowing signs traversing Europe on trucks, and their path can be blocked more effectively by the magical spells woven by the displaced and so unnatural women of Greenham Common in Britain5, who understand perfectly the cyborg networks of power.

[…]

How pure and light these new machines are! Their engineers are mystics of the sun who mediate a new scientific revolution connected to the nocturnal dream of a post-industrial society. These pure machines awaken illnesses that are “nothing more” than infinitesimal changes in the code of an antigen in the immune system, “nothing more” than the experience of intensity.

[…]

Perhaps paradoxically, we can learn from our fusion with animals and machines how not to be Human, the embodiment of Western Right Reason. From the perspective of pleasure in these multifaceted and forbidden fusions—which scientific and technological social relations have rendered inevitable—perhaps there can indeed be a feminist science.

[…]

It is unclear who constructs and who is the construction in the relationship between human and machine. It is unclear what is mind and what is body in machines that are analyzed into coding practices. To the extent that we know ourselves […] we discover that we are cyborgs, hybrids, mosaics, chimeric creatures. Biological organisms have become living systems, communication devices like others. There is no fundamental, ontological distinction in our official language between machine and organism, between technical and organic.

[…]

For us, in imagination and other practices, machines can be prosthetic inventions, personal accessories, friendly selves. We do not need organic holism to give us seamless integrity, the whole woman and its feminist variations (or perhaps mutations?).

[…]

The machine is not a thing to be animated, worshipped, and subjected. The machine is us, our processes, an aspect of our own embodiment. We have responsibility; they do not dominate or threaten us. We are responsible for the boundaries; we are they.

After these excerpts, it is redundant to observe that technology undoubtedly exerts unlimited fascination on Haraway. But no matter how enchanting the human-machine hybridism may appear, it is not sufficient to explain, unless it is addressing the most naive of readers, how these marvelous properties, these subtle psychisms, and these unparalleled capabilities of cyborgs arise. There is not even a single line of argumentation that convincingly explains why this evolving hybridism will produce a cyborg as desired by the author and not, for example, a debilitated bipedal humanoid, a merciless killing machine, or simply an overloaded gadget-laden petty bourgeois. Why, because it answers nothing of the central argument that permeates the entire manifesto, that it will happen this way because we imagine it this way, unless the goal is to allay the justified fear aroused by applied technology. And how else could it possibly answer documented, since the logic that continues Haraway’s rhetoric is precisely the one she wishes to exorcise. It is the logic of traditional bourgeois faith in science and technology, in their inherent rationality, and in the linear upward evolution of humanity toward progress. Nowhere are issues of content examined, nowhere are the deeply class-based purposes of new technologies examined, and everything is covered behind a veil of vague optimism, according to which all “boundary violations” are welcome and promising.

Unless we consider that Haraway’s position regarding “responsibility towards machines” and “responsibility in violating and drawing boundaries” implies that there is indeed a possibility that developments will not follow the noble vision of the cyborg. But this kind of political discourse, which refers to moral exhortations, is a constituent element and typical stance of the most established and proper left of the entire first world. Conflicts are set aside, creative destruction has ceased to be a strategy of capital, and all these pedestrian and outdated notions have been replaced by “social responsibility” (a popular motto of businesses now), “creativity,” and faith in progress.

Of course, Haraway’s technofetishistic stance is neither original nor even modern, despite all the cosmic futurism it carries. It is the same stance that Walter Benjamin had already warned against in a timely and accurate manner back in 1940:

The conformism, with which social democracy was familiar from the beginning, lies not only in its political tactics, but also in its economic conceptions. It constitutes one of the decisive causes of its subsequent collapse. Nothing has corrupted the German working class to such a great extent as the notion that it swims with the current. It faced technical developments as the bed of the stream, in which it was considered to be swimming. From there it was only a step to the delusion that factory work, which was supposedly tending to develop technologically, represented a political achievement.

Walter Benjamin, On the Concept of History – Theses on the Philosophy of History.

Read the entire text in the electronic library of Sarajevo.

Because faith in technology is essentially conformism, no matter how unconventional or pioneering it may pretend to be; and it is equally destructive today as it was almost a century ago.

However, we would be doing the manifesto an injustice if we do not note that, at least at one point, it does indeed acknowledge that there can be another path that leads to a revelatory destruction:

From one perspective, a cyborg world concerns the ultimate imposition of a control grid over the planet, the ultimate abstraction embodied by a Revelatory Star Wars… From another perspective, a cyborg world may have to do with lived social and bodily realities in which people do not fear their kinship with animals and machines, do not fear permanently partial identities and contradictory optics.

We are standing at a crossroads then: on the one hand Armageddon, on the other a world open, full of promises. Haraway’s answer to this dilemma begins with a deceptive metaphor and ends in a wish:

What complicates the situation with cyborgs, of course, is that they are essentially bastards of the military and patriarchal capitalism, not to mention state socialism. But bastards betray their origins with the above. At the end of the day, fathers don’t matter.

Impressive imagery, indeed, but it is a common scam. The technology of cyber-organisms is not a “bastard offspring,” as if it were a byproduct and random result of laboratory research, but a first-line construction of the military-industrial complex; it is drawn straight from the hard core of modern capitalism. And such an “offspring” does not betray its origins, nor is it about to, at least not with wishes and clever tricks. As for the “fatherless,” these specific ones are only such. The “military” and “patriarchal capitalism,” as they have proven in the most ruthless ways in the past, would prefer to turn the world upside down, to level and destroy rather than see the tip of their spear, their technological arsenal, turn against them and slip into the hands of their opponent.6

A naive approach to a fantasy, in the optimistic ’80s…

Circuit instead of classes

The rhetoric of the manifesto does not limit itself to the cyborg and its capabilities, but proceeds to interpret the new universal social model that emerged/was formed after the ruptures we discussed above. Ultimately, it provides specific political directions for the “oppositional” or “counter-political” (as it characterizes them) actions under the new conditions. Let us first examine the central points of this reasoning, and subsequently we will comment on it (the emphases are ours):

I defend a politics rooted in views about fundamental changes in the nature of order, race and gender, which are occurring in an emerging global order system that has such scope and is as unprecedented as that created by industrial capitalism; we live moving from an organic, industrial society towards a polymorphic information system – from everything as work to everything as play, play deadly.

Haraway characterizes this “polymorphic information system” as a “global system of production/reproduction and communications” or “integrated circuit” and calls it “informatics of domination”:

There are no objects, spaces, or bodies that are sacred in themselves; every component can be interconnected with any other, provided the appropriate model is constructed, the correct code for processing signals in a common language. The exchange in this world transcends the universal translation carried out by capitalist markets, which Marx analyzed so well.

[…]

The sciences of communication and modern biologies are constructed from a common movement – the translation of the world into a coding problem. […] The world is subdivided into borders with different permeability to information. Information is precisely that quantifiable element (unit, basis of unity) that allows universal translation, and therefore unimpeded instrumental power (under the name of effective communication). The greatest threat to such power is the interruption of communication. Every system collapse is a function of some pressure.

If that is the case, then capitalism—at last!—has found itself in an extremely precarious position, if it is not in immediate danger. Because if the “nature of order” has undergone fundamental changes; if the class system has been replaced by the “integrated circuit”; if labor has been replaced by “play-acting” (that is?); if the social issue is a matter of “sovereignty” and power that develops along the axis of “information”; if capitalist markets have been surpassed and no longer universally “translate” the world; if, on the contrary, the world today is now “translated” into a “coding problem”; if the greatest threat to the system is the “disruption of communication”; if, therefore, all these cataclysmic things are happening, then it simply means that the heart of capitalism, the class-organized extraction of surplus value produced by the labor of the proletariat, has ceased to function. It means that “communication technologies and biotechnologies” have become the genie that escaped from the bottle and turns against its master, and indeed right under his nose. It also means that the Leninist saying that “capitalism will make the rope with which we will hang it” comes true—only in this case, capitalism has trapped itself, in the most naive and simplistic way, and ultimately is about to hang itself. It ultimately means that everything we are experiencing today is rather an illusion or a bad dream, because otherwise it cannot be explained how the ruling class globally has not undergone any “fundamental change,” has not been replaced in its authority by “informational sovereignty,” has no “coding problem,” but, on the contrary, has been launching for thirty years the most ruthless attack against the global working class, drawing from its quiver all the “outdated” historical weapons of the past.

Words such as “sovereignty”, “integrated circuit”, “information”, “disruption of communication”, which Haraway systematically employs, may sound impressive and certainly fit the mood of the era, but not only do they fail to interpret the world, they further obscure it. The image of society as an integrated circuit, as a network of networks, is a flattening and equalizing projection that implies that all parts have an equal ability to interact with other parts and the system, systematically ignoring conflicts. Migrant workers who go on strike, armed foremen against them, police arresting the former and deporting them, and the judicial system that acquits the latter along with their bosses, do not constitute a “network” of four parties communicating information among themselves through feedback, but a conflictual episode of class war. Similarly, the figure of “sovereignty” may reveal certain characteristics of capitalist relations, but by itself it not only explains nothing, but misleads. The “worker” may exercise sovereignty over his family, and correspondingly the “supervisor” may be dominated by the company or the web of demands that regulate his role; everyone in a capitalist society can alternately or simultaneously occupy the position of “sovereign” and/or “dominated.” What such approaches ultimately serve is to muddy the waters and prepare the ground for “broader units” and cross-class alliances.

The world of Haraway’s vision emerges evolutionarily, linearly. The age of the cyborg has dawned behind the backs of the protagonists, the forces of history have been replaced by Technology (with a capital T) and conflicts have been replaced by communication and the flow of information. The old cracks and the new is already here, all without a trace of destruction. Without spilling a single drop of blood. Finally! The relentless class war ends, since the cyborg tears apart genders, sexes and classes.

Based on all of the above, it becomes clear that Haraway’s political call could have no relation to class-based or even feminist/radical characteristics; these belong to the outdated world of “civilized rational discourse.” New audiences take the place of the privileged subject:

Another basic assumption of mine is that never before has the need for unity among people trying to resist the global intensification of sovereignty been more urgent.

[…]

I would like to imagine… a cyborg society dedicated to building a political form which truly manages for a considerable period of time to hold together in unity witches, engineers, elderly people, perverts, Christians, mothers and Leninists, in order to disarm the state.

[…]

Cyborg politics is the struggle for language and the struggle against perfect communication, against a single, unique code that translates all meaning perfectly, against the central dogma of phallocentrism. For this reason, cyborg politics insists on noise, advocates for contamination, and rejoices in the anarchic fusions of animal and machine.

In Haraway’s imagination, political action becomes a hyped-up adventure of “resistance”, a technological extravaganza of “civil society”, which with unspecified tools of “noise” and “contamination” pursues maximalist goals of state disarmament. Haraway’s political manifesto is not a program, but a patchwork of sophistries that can cover everything under the umbrella of “cyborg politics”. From the “socially responsible” actions of NGOs to online petitions, and from non-violent demonstrations of political disobedience to crowdfunding and avant-garde political art videos on digital channels, everything is “noise”. Everything, but certainly not, for example, a workers’ demand, since it is an expression of an outdated “identity” and a consciousness that is obsolete in the hyper-technological new world.

If you find it difficult to grasp the possibility of a practical application of what Haraway advocates, we have an answer. Twenty years ago, what most likely represented the fullest concrete version of Haraway’s proposals began to shine within the social mainstream: the anti-globalization “movement,” which liked to characterize itself as the “movement of movements” (birth date: early 1990s – milestone date: 1999, Seattle – disappearance date: some time after 9/11, after a rapid decline and amid general indifference). All elements of the manifesto found fertile ground in anti-globalization: the representation of the movement as a “network of resistances,” the unity of all “resisters,” “globalization of sovereignty” as the ultimate enemy, global gatherings and the challenge of “noise,” new identities, tactical alliances, glorification of new technological capabilities, and political action as “playfulness.” But even then, the spectacular entrance of anti-globalization onto the stage could not hide the hollow foundations and the deceptive political agendas concealed behind the grandiose declarations. Indeed, this was the best the cyborg politics had to offer: unity among petty bourgeois and middle-class groups increasingly marginalized by the intensifying crisis/restructuring, and opportunistic alliances—sometimes with one state policy, sometimes another—depending on how much “anti-globalization” each bloc’s strategy could accommodate. Eventually, the entire “movement” turned to dust and dissolved when it became clear that “globalization” was a well-crafted collective delusion and imperialism began to bare its teeth again.7

The descendants

The rhetoric inaugurated by Haraway in 1983 regarding the cyborg as a potentially revolutionary subject did not end there, but over the past thirty years has experienced many revivals and enrichments. How else could it be, since the left-wing version of the “end of history,” that is, the “end of class analysis and the proletariat,” is an ideological component both of the crisis/restructuring and of the attack against the working class. Nor, of course, have the intellectual charlatans been absent, who, each time thinking they are riding the wave of modernity, don the prophet’s mantle and preach similar theories.

One of the best continuators of Haraway’s work is undoubtedly Antonio Negri, mainly through his works The Labor of Dionysus (1994) and Empire (2000, together with Michael Hardt). In these works, Negri adopts and extends Haraway’s cyborg. The following excerpt from “The Labor of Dionysus” is indicative:

The production of subjectivity is always a process of hybridization, of boundary-reading, and in modern history this subjective hybrid is produced increasingly within the interaction of human and machine. Today, subjectivity, stripped of all its apparently organic qualities, emerges through the factory as a brilliant technological assembly. […] The machine is an inseparable part of the subject, not as an attachment, a kind of addition – as one more of its properties; rather, the subject is simultaneously human and machine even to its core, to its very nature. The techno-scientific character of the movement for AIDS and the increasing immaterial character of social labor in general bring to light the new human nature that moves through our bodies. The cyborg is now the only available model for theorizing subjectivity. Bodies without organs, humans without qualities, cyborgs: these are the essential figures produced by the modern horizon and that produce the figures of subjects who are today capable of communism.

Removing the author’s workerist references, the excerpt could very well be included in Haraway’s manifesto. Caffentzis responded to Negri in an excellent way in 1998 with his text The End of Work or the Renaissance of Slavery?8

Over the years, Negri defined Rifkin’s “knowledge workers” as “social workers” in the 1970s and later, in the 1990s, baptized them as “cyborgs” in the manner of Donna Haraway… The social worker is the subject of “techno-scientific labor,” emerging from the pages of the Grundrisse as the cyborgs of the late twentieth century, that is, “a hybrid of machine and organism that continuously traverses the boundaries between material and immaterial labor.” While the working time of the mass worker in the production chain was broadly correlated with productivity (in exchange value and use value) and alienation from the industrial system, the working time of the social cyborg is independent of productivity but fully integrated into the field of production. Rifkin sees the “knowledge class” of “symbolic analysts” as fundamentally identified with capital… Negri, however, reads the present and future of this class differently. The existence of social cyborgs is not only proof, according to Negri, that the dialectic of capitalist development has “broken,” but also that capital simply cannot “restore” it, because “the social worker has begun to produce a subjectivity that can no longer be grasped in terms of capitalist development, understood as a completed dialectical movement.” In other words, techno-scientific labor cannot be controlled by capital through the system of wages and labor discipline, perfected by the promise of entry into the highest levels of managerial, economic, and political power for the “best.” Not only because the cyborg is beyond the limits of capitalist time and the technical means of control applied to it, but also because it is the vanguard of the communist revolution. Why? Let us first read, and then interpret what Negri says:

“The collaboration, or the association of [cyborg] producers, is positioned independently of capital’s organizational capacity. Collaboration and the subjectivity of labor have found a point of contact outside the machinery of capital. Capital simply becomes a capturing mechanism, a phantom, an idol. Around it moves the radically autonomous process of self-exploitation, which not only constitutes an alternative basis for potential development, but also essentially represents a new constitutional organization.”

Negri argues that cyborg workers have escaped from the gravitational field of capitalism into a region where their labor and their lives essentially produce the fundamental social and productive relations that pertain to communism. These relations are characterized by “self-valorization”—that is, instead of having the value of labor power and labor determined on the basis of their exchange value for capitalists, workers confer value upon their labor power through their capacity to determine their own autonomous development—and this emerges during the period when techno-scientific labor becomes exemplary. In practice, Negri’s conception of “self-valorization” is similar to that of “a class for itself” or the “class consciousness” of more traditional Marxism. But this self-valorization distinguishes the cyborg from the mass worker and signals the arrival of the true communist revolution that ironically permeates the global internet rather than the (old and new) specters of the mass worker, the landless, and the inhabitants of the planet’s ghettos.

A cyborg political / science fiction

Although thirty years have passed since its composition and despite its contradictions, generalizations, simplifications and gaps, [10] the manifesto remains a fundamental reference text on the relevant subject matter. Perhaps the reason lies exactly in its characteristics: it is so ambiguous and tangled that it makes it very easy to selectively and as one sees fit adopt it; anyone who is fascinated by science fiction can find something in it that suits them.

Stripping away the postmodern fantastic acrobatics, the manifesto proves to be far less. Despite Haraway’s declared intention to prove the dissolution of bourgeois rationality, to cleanse from the throne the beast-king of the bourgeois world, the Self with its uniqueness, and to replace the kingdom with the dominion of networks, where we are all points, intersections and nodes, the manifesto does not “sow the seeds of terror.” Because what it ultimately accomplishes is to create a labyrinthine world, a technological labyrinth, where the beast can be imprisoned, but like another Minotaur it continues relentlessly to rampage.

“Better to be a cyborg than a goddess” is the final sentence of the manifesto and Haraway’s ultimate declaration. In response to this techno-nightmare, our answer is “primitive,” drawn from the finest traditions of our proletarian ancestors a century ago and adapted to today: Neither goddesses nor cyborgs!

Harry Tuttle

- Donna Haraway was born in 1944 in Denver, USA. She studied philosophy, history, theology, literature, zoology and biology in the USA and France. She taught epistemology and women’s studies at the University of Hawaii from 1971 to 1974. She then became a professor in the Department of History of Science at Johns Hopkins University from 1974 to 1980. From 1984 until her retirement in 2011, she was a professor in the History of Consciousness program at the University of California. She is considered a celebrity in feminist and academic circles. ↩︎

- For the purposes of this text we had started to translate the manifesto, but in the process the Alexandria editions released in Greek Donna Haraway’s book Simians, Cyborgs and Women (Anthropoeides, Cyborgs and Women, September 2014) which includes it. We left the translation work (with satisfaction!) and borrowed the excerpts we present from the Alexandria edition. We preferred, however, for aesthetic reasons, to keep the original term “cyborg” instead of the cacophonous “κυβόργιο”. Also, please note, we identified some errors in the translation, which perhaps may be due to carelessness. ↩︎

- Beyond its influences on others, the manifesto itself remains extremely popular, especially in academic circles. Indicatively, searching for the term “a cyborg manifesto” on google yields 280,000 results, while the corresponding search for “class war” only 250,000. The first one wins… ↩︎

- She has stated in an interview that she probably either overlooked or perhaps fleetingly heard the already existing term “cyborg” and that she had the feeling that it emerged while she was writing. Additionally, the manifesto is the first text that Haraway wrote on a computer. ↩︎

- It refers to the “peaceful women’s camp” that operated from 1981 until 2000 outside the military base of Greenham, as a protest against the decision to install American nuclear weapons in the area. ↩︎

- Among the various shortcomings, contradictions, and simplifications of the manifesto, we must also include the one that is perhaps the most obvious. On the one hand, the stated goal is the formation of a new feminist politics. On the other hand, according to what Haraway argues, the “boundary breakdowns” and “forbidden fusions” have brought the cyborg to the foreground, nullifying earlier distinctions and identities. If then, “we are all cyborgs,” the established separations have been overcome and we are called to enthusiastically adopt the identity of this animal-human-machine hybrid, then what is the reason for a specifically “feminist” politics? ↩︎

- Among the political movements influenced by the manifesto, let us also mention the current of cyborg-feminism, which however has negligible resonance and furthermore some critics classify it more among artistic rather than political currents and point out that it has replaced woman-as-nature with technology-as-woman. ↩︎

- George Caffentzis, The End of Work or the Revival of Slavery? A Critique of Rifkin and Negri. It is worth reading it in full and you will find it in the library of Sarajevo. ↩︎