This essay by Margaret Wertheim was published in Greek in the magazine futura no. 5, Winter 1998 – 1999, from which we republish it. It was included in the collective book Architecture of Fear (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1997). The translation into Greek was done by E. Matzaridou and the editing by V. Sotirior.

In 2000 Margaret Wertheim published a book with a similar title: The Pearly Gates of Cyberspace: A History of Space from Dante to the Internet.

Margaret Wertheim is an Australian writer, specializing in the history of physics and the cultural / ideological parameters of it.

The “pearly gates” are a Christian representation / fantasy of the entrance to paradise.

Born from military fears in the 1960s, cyberspace has, in recent years, broken out of the ivory tower and exploded into the public consciousness. With more than fifty million users surfing the Internet, cyberspace is, quite clearly, the “territory” that has grown faster than any other in world history. Once the province only of computer specialists, with the invention of the user-friendly World Wide Web, cyberspace has turned into a truly public space.

The mere availability of network technology, however, is not enough to explain why the public rushed to embrace cyberspace with such enthusiasm. People do not accept a technology just because it exists. A need must arise. There must be a latent desire waiting to be satisfied. What is the desire that cyberspace echoes? In short, what is the psychological void that the Internet fills? If the soldier’s motive was fear, what is the motive that drives this frenzied citizen’s rush into networked space? In this essay I propose, as a psychological phenomenon, that today’s sudden fixation on cyberspace can be seen as a modern parallel to the explosion of Christianity after the collapse of the Roman Empire. Specifically, I want to sketch an analogy between Cyberspace and the Christian conception of Paradise.

Just as the early Christians viewed paradise as an idealized kingdom beyond the chaos and decay of the material world – the degradation was so obvious as the empire collapsed around them – so today’s converts to cyberspace proclaim their realm as an ideal kingdom “above” and “beyond” the problems of the material world. While the first Christians spread the word that paradise is the kingdom where the human soul would be freed from the weaknesses and defects of the flesh, today’s cyberspace champions hail it as a place where they will liberate themselves from the limitations of physical existence. Like paradise, cyberspace purges us, supposedly, from the “sins” of the body. In short, cyberspace, like paradise, is announced as a supreme field; a metaphysical kingdom for the soul itself.

They also told us that age, race, and gender would become obsolete in the emerging digital democracy. Just as paradise is open to all who follow the teachings of Christ, so cyberspace is open to anyone who can have a personal computer and a relatively cheap monthly internet subscription. Like the kingdom of Christ, cyberspace extends its welcome to the entire human race—at least that is what it claims.

In his book Travels in Hyperreality, Umberto Eco sketches a parallel between the final years of the Roman Empire and America at the end of the 20th century. The weakening of centralized government, the gradual dissolution of national cohesion, and the collapse of the welfare state leave ancient Rome and America, at the end of the 20th century, open to internal rupture and collapse. “The collapse of the Great Pax (simultaneously military, political, social, and cultural) ushers in a period of economic crisis and a power vacuum.”1 In this vacuum Eco locates the seeds of feudalism, where, in place of central authority, people are left to be dominated by various fiefs. The modern counterpart of the feudal lord is, of course, the multinational corporation.

As secular power loses its prestige, people turn back to secret, magical, cultic and religious forms to give support to their lives. Ancient Rome was a cauldron of mystico-religious ferment, from the ascetic number-mysticism of Neoplatonism to the hedonistic cult of Dionysus, to the Eastern religions of Mithras and Astarte. During the same period, a great wave of religious passion swept in, bringing with it the followers of a certain Jesus of Nazareth.

Unlike the Jews, from whom they had split off, these “Christians” opened their religious group to everyone. One did not need to be born a Christian; a simple baptism sufficed. Historians have observed that Christianity was essentially a democratic religion, and in its early years it was particularly welcoming to women. In Judaism, notes historian Gerda Lerner, not only were women relegated to a separate women’s gallery and denied all education in the Torah, but the covenant with God concerned only men: it was the act of circumcision.2 Christianity, at first, showed no special treatment based on gender. Indeed, religion scholar Elaine Pagels demonstrated that some early forms of Christianity allowed women to become priests.3 Christianity’s major innovation was its promises of salvation and redemption for everyone, regardless of class, race, or nationality. The kingdom of paradise was open to all. All one had to do was embrace the teachings of Christ and, of course, abide by them. By the end of the 4th century Christianity had become the official religion of Rome. Sixteen hundred years later, Eco reminds us that “it is common currency in today’s historiography that we are living amid the crisis of the Pax Americana”.4

The rapid decline of the central government and the collapse of the “empire” are frequent topics in the daily news. The “barbarians” are at our gates: the “Latin hordes” from the South, who, we are told, will wipe out our social security and healthcare systems, and the “yellow hordes” of Asia that supposedly steal our jobs with their cheap labour and depress our economy with their counterfeit electronics and mass-produced clothes. The immigration legislation is our own Hadrian’s Wall.

In response, the Americans, like the Romans, turn back to religion for support in their lives. American society today is seized by a palpable yearning for spirituality, whether it is the doctrine of the Christian Coalition, California-style mysticism, or the pseudo-Native Americanism of an executive retreating to his secluded home. Cyberspace is not a religious construct; indeed, many net users may avoid religion per se. Nevertheless, its appeal can be understood mainly in religious terms. I argue that the role cyberspace plays in the contemporary popular imagination, while not the product of a conscious theology, is not dissimilar to that which paradise played in the early Christian imagination. While not an openly religious construct, it is nonetheless a “church”—because of the religious role it plays for many contemporary Americans. In the scientific age, overt displays of religiosity make many people uncomfortable. The appeal of cyberspace, therefore, lies precisely in this paradox: it repackages the old idea of paradise, but presents it in a secular and technologically approved way. The “perfect” kingdom awaits us, we are told, not beyond the pearly gates but beyond the gateways of the network. Behind the electronic doors labeled “com,” “net,” and “edu.”

The very fact that science itself has displayed a technological substitute for paradise should not surprise us, as the English philosopher Mary Midgley wrote, for example: “The idea that we can achieve salvation through science is old and powerful… Any system of thought that holds the dominant role science now holds in our lives must form corresponding myths and mark our imagination deeply. It is not simply a useful tool. It is also a model we follow at a deep level in trying to meet our imaginative needs.”5

The belief in salvation through science and its technological byproducts is nowhere deeper than in America. In a society passionate about technology, cyberspace almost inevitably becomes the modern vision of paradise—the metaphysical apotheosis of “technological” grandeur.

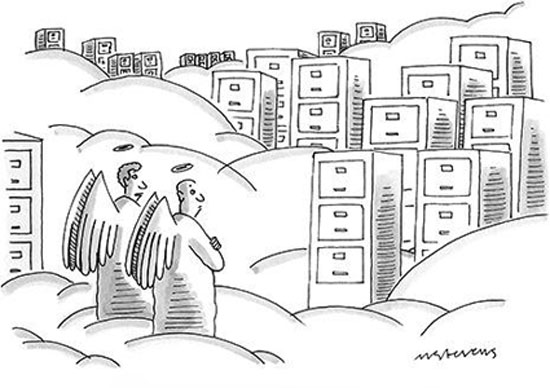

Having outlined the main points of my analogy, let me now express the parallels between cyberspace and paradise, because while some are immediately obvious, I believe others are not. Certainly one of the key similarities lies in the democratic promise of access to all. Men and women, the First and Third Worlds, North and South, West and East—cyberspace is equally open to everyone. At least at the beginning. Like paradise, cyberspace has no national borders; it is a space beyond “space,” where men and women from all nations can meet with mutual ease and equal access. Indeed, we have been told, cyberspace eliminates barriers such as gender, race, and nationality, turning each person into a disembodied digital stream. As with Christianity, there is something truly positive here for women and minorities. Many commentators have rightly pointed out that cyberspace may offer women freedom from the constant pressure of sexual harassment and gender-based judgment. A similar argument has been made for race. Therefore, we might agree with Laurie Anderson, who argues that in cyberspace one becomes, in a sense, an angel—an entity of the ether freed from the burden of gender and color prejudice. Hermaphroditic, racially amorphous, and chronologically indeterminate, the cybernaut, like the angel, is an “ideal” being. At least, that is the dream.

The irony is that cybernauts use a physical, muscular metaphor for their journeys in hyper-reality. To “surf” the net does not evoke images of disembodied everyday life, but a vision of physical power, both for the human agent and for the space itself. Where the cybernaut is endowed with the grace and dexterity of the surfer, the space is likened to the ocean. Here the paradox again comes to the fore. In a realm of disembodiment, we were promised the illusion of physical perfection. Angels, of course, were also perfect in form. Graceful, sublime and adorned with the ultimate stylish accessory—wings—they were the medieval “beautiful people.” Like an angel, the cybernaut is freed from the aesthetic sins of the body. Bad breath, ugly hair, acne, dandruff, lameness, squints, obesity and wrinkles: all forgotten in the material world. Cyberspace philosopher Allucquere Rozanne Stone has stressed that this aspect of cyberspace exerts a particular attraction on boys in adolescence. With their bodies undergoing frightening continual change, teenagers, she says, see cyberspace as a kingdom in which to escape the “sense of losing control” that accompanies the embodiment of the male “teen.”6 Unable to control their mutating flesh, they rush into a realm where they regain power and control. It is no accident that the pirates and surfers of the Net are, for the most part, male.

Cybernauts are liberated not only from the sins of their own bodies but also from those of others. In the age of AIDS cyberspace offers a place where one can have safe relationships. In the 1970s Americans went to bars and discos in search of partners. In the 1980s they went to gyms and clubs. But today such choices entail serious risks. Apart from catching a sexually transmitted disease, you run the risk of being raped or attacked at night while roaming a vast American city. It is so much safer to log on, where romance can be found without leaving your living room. Stories of cyber-romance and cyber-sex are plentiful. What could be safer or purer than absolutely disembodied love? A Christian ideal, if ever there was one.

According to the New York artist Adrianne Wortzel, cyberspace also liberates us from psychological constraints. In America today, she claims, many people do not feel they can express themselves freely in their real lives. She refers to how more and more Americans, living in a culture dominated by TV sitcoms, feel compelled to adopt a cheerful demeanor and present a caricatured face to the rest of the world.

But such a distortion of the real self cannot continue for long without wounding the soul, and Wortzel believes that cyberspace offers a therapeutic escape, giving an outlet to their “real selves.” And if you don’t know who your real self is, cyberspace is a place where you can simply create a character and try it out. Gender switching is perhaps the most common experiment tried by cybernauts, but by no means the only one. In MUDs players transform into witches, satanists, princesses, and monsters. Indeed, says Wortzel, such realms are populated by human-animal hybrids, as players experiment with the limits of the human. Even in ordinary “chat rooms,” the cybernaut can “be” anything for as long as he or she can adopt a convincing behavior. The shy, hesitant type can turn into a teaser, the neurotic into a sex diva. On the net, personality can be exercised and played to the fullest extent. Realizing and expressing the “real self” is, of course, a central religious theme, not only in Christianity. An additional aspect of the cyber-revolution that draws attention in any analysis of parallels with early Christianity is the emphasis placed on images. Although at the moment most communication and information on the net is still in text form, the situation is changing rapidly. With the arrival of the www and the new network tools, images are multiplying and many cyber-experts believe that the image is the future. Instead of sending text messages to one another, we will be able to send real-time video, or “agent” programs to interact on our behalf. The data itself will take the form of graphic landscapes, realizing William Gibson’s vision of an iconic datascape.7

Meanwhile, virtual schoolrooms and libraries are supposed to supply the inquisitive mind with an endless range of interactive visual innovations, designed to awaken even the most indifferent students and keep them alert.

Dr. Diane Ravitch, former official of the U.S. Department of Education, writes: In this new world of pedagogical abundance, children and adults alike will be able to select a program on their television and learn whatever they want, under conditions that best serve them… Young John may decide that he wants to learn the history of modern Japan, something he can do by calling up the authorities and experts on the subject, who will not only use exciting graphics and images but will also narrate the story in video, a fact that will stimulate the learner’s curiosity and imagination.8

The Internet will be an ocean of images, where everything will be converted into image form for easy mental digestion and maximum entertainment value. Why read when you can watch?

The emphasis on imagery was a medieval issue when churches became temples of art. At that time, ecclesiastical art was not merely decorative. In an era of ignorance and illiteracy it served the education of the population in the Christian worldview. The painted images with stories from the Bible, of Christ, the Virgin Mary and the saints were beautiful, but they did much more than that. Thus, just as television documentaries educate us today, religious art literally taught people about Christian cosmology. Not only cosmology, but also history, biology, agriculture, social sciences, ethics and metaphysics were embedded in religious art. The Christian era was nothing if not visual, and the Church Fathers understood well how to exert power through imagery.

So, just as images played an important educational role at that time, they likewise tell us now that images will fill the educational gap in the era of cyberspace.

In another sense, cyberspace signals a return to our medieval past, since cyberspace, like paradise, is a metaphysical rather than a natural construct. In this sense it represents a dramatic reversal of the last five hundred years of Western history, which, since the Renaissance—and particularly since the 17th century—has increasingly focused on natural thought.

The emergence of the individual that characterized Renaissance culture presupposes an awakening of the body and of physical space. After the metaphysical obsessions of the Middle Ages, the artists of the Renaissance turned their attention outward, to the material world: to the beauty of bodies, landscape and natural form. The development of perspective in representation was not merely an artistic invention. It entailed a systematic investigation of the nature of physical space, which prepared the Western mind for the revolution in the natural sciences carried out by pioneers such as Copernicus, Kepler and Galileo. The principal outcome of this revolution was to extract Europe from the metaphysical cosmology of the medieval period and to place humanity firmly within a materialist substrate – the mathematized physical cosmology inherited by us from Newton.

Since the 17th century, Western science has been a process of gradually manipulating, with ever-increasing detail, the natural world that surrounds us. Today, scientists have mapped the physical arena at every perceivable scale, from the subatomic level to the cosmic. We have mapped every inch of our own planet (and a good part of Venus and Mars as well). In a way no member of our species ever managed in the past, we can now locate ourselves precisely—geographically and astronomically—in our universe; yet so far this obsessive exploration of space has been fruitless, for what we have discovered is mainly a vast, cold, empty void. Years of scanning the skies with radio telescopes have yielded no confirmed message from the stars. Unlike our medieval ancestors, who lived in a world teeming with other intelligent beings (angels, archangels, cherubim, seraphim, etc.), we find ourselves absolutely alone. The immense expanse of physical space—billions of light-years of emptiness and dust—renders this loneliness ever more unbearable and diminishes our hopes for cosmic coexistence. The relentless exploration of physical space and the concomitant materialist philosophy of nature that has become the defining principle of the “modern” Western era have turned us into meaningless organic cells in a sterile void.

Our dreams of space have long been accompanied by the belief that we would find friends among the stars. The shattering of that hope (brought low by NASA’s visits to the barren, lifeless planets of Mars and Venus, and by the absence of any clear response from the SETI program) has bred a certain hesitancy toward space exploration. People are disturbed by the void. Not only do they need companions, they need spiritual contact as well. Space offers us neither. Stripping the universe not only of angels and gods, but also of spiritual encounters, physical cosmology has confined us to being merely physical beings.

I suppose the massive appeal of cyberspace stems from the fact that many people hope it can fill that void in their lives. Thus, in a very special way, cyberspace represents a return to medieval perceptions because it shifts the focus again from the physical to the metaphysical, from the body to the soul—not only for the individual but for society as a whole. Because cyberspace is above all a field of communication, a gathering with other people—more than fifty million of them already, and it expands every day. Like paradise, cyberspace was sold to us as a common place where the orders of the faithful would communicate with one another in a “paradise” of brotherly love, liberated from the tyranny of distance and flesh.

In this era of alienation and social disintegration, is it strange that we feel fascinated by such a vision? Like paradise, cyberspace is a place where we are promised the joys of freedom, power, connection, even love; a realm where the weaknesses of the body will vanish, where the soul will be free to express itself fully, where image and imagination will merge, and where, through the development of online databases, everything will become known. In such a space we will not only be angels, but gods; not mere slaves, but masters of our fate.

Whether cyberspace can fulfill this vision is, of course, another matter.

We republish the above text not because we agree with its analytical approach, but because we consider it useful for reflection. Soon, however, we must present at least one fundamental disagreement. Wertheim compares cyberspace to the Christian church, but bypasses every form of “secular metaphysics” that has been cultivated and developed since the 19th century, within and for the sake of capitalism. She especially bypasses commodity fetishism and all its extensions into social relations. If the special allure of cyberspace and the mass dependence on digital virtuality are analysed as the most recent version so far of this metaphysics and this fetishism, then one may indeed uncover genealogical links with religion (Christianity, and not only that) but also much else.

Of course, in her 1997 essay Margaret Wertheim could hardly have taken into account the spectacular evolution of the internet regarding its social uses and the generalized digital mediation of these relations as they are today. She could not even have foreseen the role of this generalized mediation in mass surveillance. Thus, while we find the suggestion of a “sanctification” of the new (information) machines and their capacities interesting, we judge that there is much more to be identified beyond the mere comparison with medieval Christianity.

Ziggy Stardust

- Umberto Eco, Travels in Hyperreality (San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1986), 75. ↩︎

- Gerda Lerner, The Creation of Patriarchy (New York: Oxford University Press, 1986), 200-01. ↩︎

- Elaine Pagels, The Gnostic Gospels (New York: Vintage Books, 1981), 60-61. ↩︎

- Echo, loc. cit. 75. ↩︎

- Mary Midgley, Science as Salvation: A Modern Myth and its Meaning (London: Routledge, 1992), 1. ↩︎

- Allucquere Rosanne Stone, “Will the Real Body Please Stand Up?: Boundary Stories About Virtual Cultures”, in Cyberspace: First Steps, ed. Michale Benedikt (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1992), 107. ↩︎

- William Gibson, Neuromancer (New York: Ace Books, 1984). ↩︎

- Dr. Diane Ravitch, referring to Neil Postman “Princeton Architectural Press, Virtual Students, Digital Classroom”, The Nation (9 October 1995): 377. ↩︎