Every modern computer is, in essence, supposed to be a physical implementation of an ideal machine, the universal Turing machine that can compute any computable function. Extremely simple in conception, a Turing machine consists of a paper tape containing a series of symbols, a head that reads from and writes to the tape, a register holding the machine’s state, and an instruction table with a sequence of commands—moves (write, erase, read, shift)—that the head must execute. Turing machines were never built in this form for tackling real-world problems. They were the outcome of a thought experiment conducted by Turing in his effort to break down the process of mathematical proof into a series of very simple and “mechanical” steps.

But how did he come up with the idea for such a machine? What is that machine that looks overwhelmingly like the Turing machine? The humble little typewriter… The resemblance seems to be no coincidence. Biographers of Turing mention that his mother owned such a typewriter, which little Alan was thrilled with. They even say that he had the ambition to become a manufacturer and inventor of typewriters. The typewriter’s paper as the tape of the universal machine, the cylinder as the head, the shift key (from uppercase to lowercase and vice versa) as the state register. Most of the elements of the Turing machine already existed in the typewriters of his time. Alan only needed to add, for his own purposes, the ability to read (and not just write) from the tape, along with the instruction table.

There are such small anecdotes within the history of science that capture, in a nutshell, the complex relationships between techno-science and its social environment. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, typewriters were not simply a curiosity for those who wished to send more elegant letters. Along with the first filing systems, early mechanical calculators, and a range of other office devices (even cash registers), they constituted the arsenal of states and businesses in their effort to rationalize and automate “intellectual” labor in the office jobs of the time (and women secretaries were among the first to use them).

A thread, then, connecting the humble basements of labour restructuring with the high plateaus of the purest mathematical thought. Without typewriters, would there be no computers? Is that the conclusion? Not exactly. Something else would have been found as a vehicle for the universal machine. After all, another mathematician of the time, Emil Post, describing his own version of the computing machine, had used the example of a worker (that was the word, “worker”) in front of a chain of paper boxes. Yet it seems that, whether in the form of a typewriter or in the form of the assembly line, the generalised tendency towards bureaucratisation and automation of production (and “intellectual” production) at the turn of the century could not be ignored, even by the most high-minded mathematicians. It was there, in front of them, all around them, demanding to find its technological expression and completion. And computing machines were one facet of that completion.

Photos:

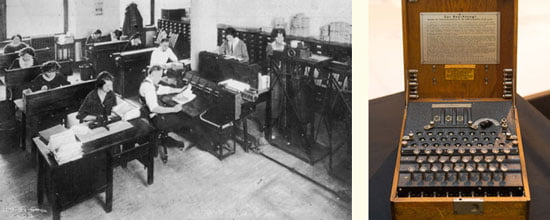

Left: a typical data-processing office with punched cards. 1920s, before Turing conceived his universal machine. How many office machines can you count?

Right: A highly advanced electro-mechanical typewriter was the tangible tool of the German army’s encrypted communications in World War II (“Enigma”). It was no coincidence but rather a kind of “historical determinism” that the machine which had impressed the young Turing (and thousands of others) reappeared before him as a “mystery”….