the brain: the new big trick

The engagement, to an obsessive degree, with the human (and not only) genome within technoscientific laboratories around the world is rather well known. And one doesn’t need to be a specialist to have an idea of the relevant developments. Popular science books, documentaries, newspaper articles and, of course, the mass culture mega-machine called cinema never miss an opportunity to enlighten us about the miracles (or traumas) of genetics.1 However, there is another side of biotechno-capitalist development that (wrongly, in our opinion) does not always receive equivalent attention. Perhaps because, at least for now, it does not have practical applications to show to a comparable extent and with the corresponding effectiveness. We are referring to all those scientific branches that fall under the broad term “neurosciences.” As a specialized branch of biology, it is not particularly new. The birth of neuroscience in its modern form, which focuses essentially on the brain and neurons as the basic functional unit of the nervous system, dates back to the end of the 19th century and to the experiments of Golgi and Cajal that allowed the visualization of neurons and their ramifications. And from this perspective, neuroscience is somewhat older than genetics.

Without having particularly researched the history of neuroscience, our sense is that it did not follow the frenzied course of genetics2. However, something that has begun to change in the last three decades. From a technical point of view, at least two factors contributed to the renaissance of neuroscience. On one hand, it was the development of new methods for recording brain activity (such as the dubious reliability, or rather ambiguous interpretability, imaging techniques, like fMRI) and on the other hand, the increase in computer power that opened the way for the development of computational models of biological neural networks. From a technical point of view… Because this alone is not sufficient to explain the neuro-revival. But we will discuss the non-technical causes of this renaissance below.

For those who may not know, therefore, the 1990s had been declared by the American government as the “decade of the brain.” In (scientific) practice, however, this declaration did not really mean much, as it appears that its goal was more the dissemination of the results of neuroscience research to a broader audience. Or, to use less rounded and euphemistic words, propaganda and proselytism and whatever else can fall under the term “ideological preprocessing.” The next (and more serious) steps were taken much more recently, following the model of the Human Genome Project from genetics. In 2013, the American government under Obama announced the launch of the BRAIN initiative, a relatively long-term funding program aimed at the systematic study of the brain. The complete mapping of neurons and their interconnections is considered a key stake of the program, through and via the development of exotic (by today’s standards) technologies for measuring brain activity and interacting with it, such as nanodevices and devices based on synthetic biology. In the same year, the European Union announced the launch of its own (and correspondingly ambitious) brain study program, the Human Brain Project. It is important here to understand that these are not simply pile-up funding programs, like so many that come out every year, but programs considered as fundamental pillars of scientific research. Indicatively, we note that the European Human Brain Project holds the position of flagship project, that is, it is a central program of enormous scope and funding. And there are not many such projects. In fact, apart from the Human Brain Project, only one other holds the corresponding position – Graphene, for the study of the properties and potential applications of graphene.

Thus, the brain is now officially transformed into a central focus point of techno-scientific attention. And the ambitions of those involved in related programs seem to have no limits. A simple listing of the relevant scientific (or pseudo-scientific) fields that have emerged and bear the prefix “neuro-” is enough to give an idea of the extent of these ambitions: neuro-psychiatry (expected), neuro-anthropology, neuro-linguistics, neuro-economics (Mars would hardly be missing from Lent!), neuro-education3, neuro-aesthetics, neuro-theology (oh yes, indeed!), social neuroscience, and the list goes on. In this article, we will focus mainly on the last member of the above list, so-called social neuroscience.

are you your brain (;)

Like every branch with excessive ambitions, neuroscience has not avoided the well-known ideological trick: it presents itself with grandiose statements, as if it were something unprecedented in the history of humanity, which will lead to unprecedented discoveries about human nature as a whole – or, to put it in terms of a Hegelian-Marxist philosophy, it presents the partial as universal. We will limit ourselves to words that come exclusively from the lips of neuroscientists themselves, avoiding those of non-experts who could be accused of “misinterpretations.” As a neuroscientific “manifesto” informs us, then:4

“Thought and consciousness have not fallen from the sky; on the contrary, they have gradually developed during the evolution of the nervous system. Perhaps this is the most important knowledge that modern neuroscience has offered us.

…

This means that we can now consistently and unambiguously treat thought, consciousness, emotions, intentional actions, and free will as natural processes, since they are based on other processes that are biological.

…

The results from brain research will lead us to a change in the image we have of humanity. Gradually, they will eliminate dualistic perceptions, such as those regarding the separation of body and spirit.

…

All this progress, however, does not mean that we will end up with some form of neural reductionism. Even if we someday reach the point of clarifying all the neural processes underlying the compassion we feel for other people, love, and moral responsibility, these ‘inner perspectives’ of humanity will maintain their independence. For, even if someone has precisely understood the way a Bach fugue was written, our enthusiasm for it does not diminish at all. Brain research must clearly distinguish what things it can speak about and what lies outside its jurisdiction; just as musicology has something to tell us about Bach’s fugue – to stay with this example – but must remain silent regarding what it is that gives it its particular beauty.”

And a scientific handbook on social neuroscience states in its introduction5:

“Social neuroscience deals with fundamental questions regarding cognition and the dynamic interactions it has with both the brain’s biological systems and the social world in which it is situated. It is a field that studies the relationship between neural and social processes, including those of the intermediate information processing components at both the neural and computational level of analysis.

…

The assumption that social neuroscience makes… is that… the mechanisms underlying cognition and behavior will not find a complete explanation through an approach that is either purely biological or exclusively social. Perhaps a multi-level and integrative analysis and a common scientific language – based on the structure and function of the brain and biology – could help achieve this goal. Every human behavior, at one level, is biological; something that however does not mean that a biological reduction offers a simple, unique, and satisfactory explanation of complex behaviors or that molecular forms of representation provide the only or best analysis for understanding human behavior.”

Much could be commented on the above excerpts. We will start with a simple and “naive” question. Exactly where does the conviction of neuroscientists arise that the study of the brain can not only contribute to understanding consciousness and social behavior, but also that it will radically change the image we have of human beings? On what exactly is it based? Leaving aside for now various philosophical issues that arise here, it is worth noting from the outset the following very basic point that is not emphasized enough: all these manifestos and declarations are not based on experimental data. Without this of course meaning that experimental research is not being conducted in such directions.

To explain this “paradox,” we will give an example, related to the famous “mirror neurons”:

“There is an increasing body of literature that appears to confirm the idea that we understand the behavior of other people, partly through simulation… Imaging studies show that observing and mimicking the actions of another person activates the premotor cortex. This activation is somatotopic with respect to the observed body part performing the action, even when the observing subject is not performing any visible action. Indeed, so-called ‘mirror neurons’ have been discovered in both humans and monkeys. These neurons respond both when the subject performs a specific action and when they simply observe another person performing the same action. Damage to the somatosensory cortex results in difficulties recognizing complex emotions through observing facial expressions…”

«Cognitive neuroscience of human social behaviour», Nature (Neuroscience Reviews), 2003

The image below shows the relevant experimental results. Broadly speaking, the redder a brain region is (unfortunately we are noir here – you should look for the image on the site…), the more “likely” it is that damage to that region will result in an inability to understand another person’s emotional state. The reason we mention this example along with the image is not to dwell on the technical details of the experimental procedure, but because this example is a typical sample of such research and its logic. These are studies which, especially in social neuroscience, rely heavily on methods of imaging brain activity (mainly fMRI and PET). From such images obtained from a series of subjects, some averages are then calculated, a “mean” brain image, and finally this image is statistically correlated with this or that disorder or peculiarity. One does not need to be a mathematician to understand that such a process requires special attention both regarding the correlations derived and the way these should be interpreted. For example, the phrase “Lesions in the somatosensory cortex result in difficulties recognizing complex emotions” could very easily mean that six out of ten of those who had such lesions also exhibited the associated disorder. Which in turn means that it is not unlikely that some had such lesions but no disorder at all. But at a second level, such a correlation, even with very high probability, does not imply a causal relationship. The lesion correlated with a disorder may simply be a side effect of some other, deeper lesion, which is the real cause. These observations do not, of course, bring owls to Athens. At least in theoretical terms, it is assumed to be common knowledge among scientists in every field. Practice, however, shows the opposite. The misuse of these correlation-extraction methods has reached such a point within the neurosciences that criticisms have now begun to emerge even from within – and they have been given the appropriate name: voodoo correlations. However, from our perspective, our purpose is not to wag a finger at neuroscientists in a schoolmasterly manner to bring them back in line. The very fact that so many questionable studies are published is indicative of a specific trend: a “strategy” that attempts to place the brain in a central position in relation to the study of the “phenomena” of consciousness and social behavior, without there even being solid experimental findings supporting such centrality.6

Going one step further, let us first assume that a study such as that on mirror neurons does not suffer from experimental flaws and interpretative acrobatics. What exactly “revolutionary” does it have to offer for understanding human social behavior? To what extent does it “radically” change the image we have of human beings, as proclaimed and threatened by all sorts of manifestos in the field? That primary mammals (and not only) have a particularly strong mimetic ability, and that humans especially reproduce in their minds actions and events from both the past and the possible future, is something that does not require much wisdom to understand and accept. Likewise, it is not at all “astonishing” that the brain is involved. This is not an isolated case particularly related to this specific research. The majority of studies in social neuroscience (we would say all, but we reserve ourselves, since we are not specialists) follow the same pattern of presenting completely commonplace, even naive, findings of a “sociological” type, combined with experiments that correlate behaviors with specific brain regions or functions.

However, if such studies do not offer anything particularly profound—at least not to those who have read a couple of relevant books in their lifetime or have simply learned to observe human behavior—they still effectively perform another function, one of an ideological nature. They attempt, covertly, to subsume all social “phenomena” under the jurisdiction and methodology of the neurosciences. A phenomenon attains its “truth” and “reality” only to the extent that it can be neuroscientifically “verified.” The very existence of so many neuro-“something” branches (even neuro-theology!) indicates their tendency to be colonized by the neuron… pure and simple. A reverse example might be useful here. Radiometric dating methods are systematically used in several fields that require as accurate as possible age calculations of various samples, such as, for instance, archaeology and paleontology. And rightly so—the relevant fields do well to use such methods. Only, we have not yet succumbed to notions such as radio-anthropology, radio-economics, or radio-theology! Thus, despite the numerous (ineffective) warnings against neural reductionism abundant in neuro-manifestos, it is precisely this reductionism that remains the ultimate stake… in the final analysis.7

A final observation regarding the ideological aspect of these studies—which may be of lesser importance; or perhaps not. We have the impression that the centrality of imaging methods in social neuroscience tends to cultivate a “metaphysics of the image.” Practicing science in terms of spectacle appears, and to a certain extent indeed is, “counterproductive.” However, it can be extremely “productive” for a field in a phase of colonial expansion that needs to conquer territories and minds. After all, barely “only” a century has passed since the brain was popularly presented (?) as an “internal cinema,” modeled after that then-novel spectacle machine. Times have changed, and now it is presented as a “network” whose interconnections and interactions must be mapped and visualized—in other words, in the form that today’s spectacle machine has taken…

but your brain is a computer?

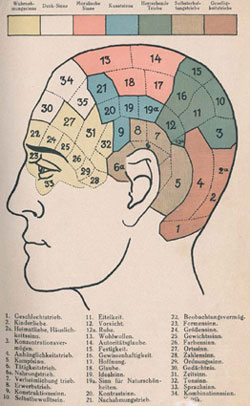

Given that specific brain regions were considered responsible for specific skills, the wisdom of phrenology claimed that an underdeveloped skill resulted in the enlargement of the corresponding brain region, which in turn influenced the shaping of the overlying cranial areas. Areas 2 and 2a are responsible for feelings of love towards children, home life, and the homeland!

From a German book of 1921, as republished in F. Vidal’s article «Le sujet cérébral: une esquisse historique et conceptuelle».

A sentence such as “the amygdala is a structure that participates in the stages of post-sensory processing, as it receives processed visual information from the anterior temporal cortex and stores the codes needed for subsequent processing of sensory information in other brain regions”8 is a typical sample of the language one encounters when taking the trouble to read scientific articles from the field of (social) neuroscience. To the eyes of a non-specialist, the above most likely resembles a techno-scientific jargon, inaccessible to the uninitiated. From a non-technical perspective, however, what is particularly interesting is the description of the brain and its functions in terms of information, processing, storage, and code; with terminology that directly evokes computer science and cybernetics9. In other words, the internal mental states of an individual are perceived as those states in which a complex computational machine – the brain in question – can find itself during the processing of information received from the external world. Thus, behind a first-level neural reductionism, another type emerges, this time of an informational nature (in the relevant literature usually referred to as computationalism). Not only is (social) consciousness reduced to brain functions, but these in turn are reduced to computational steps of a machine. Only this second step of reductionism essentially constitutes a metaphysical theoretical commitment. It is theoretical in the sense that whether it is legitimate or not escapes purely technical assessment and is a philosophical matter, ultimately social and political. And it becomes metaphysical in degree to which it is uncritically accepted by the involved scientists as the unquestionable criterion by which the “truth” of any social “phenomenon” must be judged.

Or perhaps not? New brain imaging methods seem to have led to a resurgence of “phrenology,” albeit in a different form. They are extensively used to identify brain regions associated (always statistically…) with every kind of skill, disease, and dysfunction. Here, positron emission tomography (PET) imaging is employed to study mental retardation and depression (as republished in the article by F. Vidal «Le sujet cérébral: une esquisse historique et conceptuelle»).

What exactly does the notion that the brain – and ultimately consciousness – is a computing machine imply?10 A machine, in order to function as a computing device, must operate based on abstract, formal-type rules. In other words, such a machine is indifferent to the source of its input data, as long as these data have first undergone an abstract process of conversion into clear, unambiguous symbols. Therefore, a necessary condition is the existence of a gap between the machine’s “inner self” and the “outer world,” bridged through appropriate interfaces. The symbols and the rules for their processing preexist these interfaces; they are like a primordial ontological substratum. And why is this significant? Because if the brain is considered such a machine, then it must also be regarded as primordially detached from the world, folded inward into its own “self,” only secondarily bridging this gap through the interface called the “rest of the body.” The Ego is not a body but identifies with the brain, which has a body as an object to possess.

However, theoretically speaking, there is no reason to consider such a position as self-evident. We quote below a nice excerpt from a text by Tim Ingold:11

“Perhaps it is time for all linguistically naive and unlearned people to put linguists in their place. Because, unlike a linguist, a simple speaker is not only not a distanced, self-reflexive subject placed before an external reality, but is embedded within a world full of relational contexts, being absolutely immersed in it from the outset. For such a being, this world is already loaded with meanings: meaning is inherent in the relationships between the inhabiting being and the parts of the inhabited world. And to the extent that people inhabit the same world, following a common stream of activities, they cannot but share common meanings. This community of experiences, the awareness of living within a common world of meaning-laden relationships, establishes a foundational sociality that exists, to use Pierre Bourdieu’s words, on the ‘hither side of words and concepts’ and constitutes the cornerstone upon which all subsequent efforts at verbal communication are built. Because, despite the undeniable verbal conventions employed in speech, we do not receive these conventions ready-made. They are continuously in a process of construction and reconstruction, accumulating the history of their previous uses: each one represents an achievement of previous generations, through a hard and perilous struggle to make themselves understood by others. Each time we speak of the conventional meaning of a word, we essentially presuppose all this history silently, putting it ‘within parentheses.’ Thus, we tend to perceive usage as founded upon convention, whereas, in reality, it is only through usage that convention can be established and maintained. Therefore, to understand how words acquire their meaning, we must re-embed them within the original stream of their sociality, within the specific actional and relational contexts in which they are used and in shaping which they participate. Ultimately arriving at the realization that words are far from deriving their meaning through their attachment to mental concepts imposed from without upon a meaningless world of entities and events located ‘out there somewhere.’ On the contrary, they derive their meaning from the relational properties of the world itself. Every word is a story in condensed and compact form.”

Ingold here critically refers to the dominant linguistic theories of structuralist origin, for which the so-called arbitrariness of the sign is something like an article of faith. However, the same critique can be turned against the dominant neuroscientific theories, since both share the same cybernetic–informational substratum (in the same text, Ingold examines the concept of intelligence in a similar way). It is not only words that constitute histories in condensed and compact form, but also every thought and every social behavior. The celebratory proclamations about transcending Cartesian dualism between body and spirit are part of the daily agenda of neuroscientists; yet they seem to steadfastly adhere to another aspect of Cartesian philosophy: the centrality of the individual subject12.

It is precisely this insistence on a notion of unmediated subjectivity that renders social neuroscience incapable of going beyond the formulation of familiar commonplaces. Even in the best cases, when the influence of factors exceeding the individual on consciousness is acknowledged, this influence is perceived in evolutionary terms: as the result of the phylogenetic history of the human species. During the evolution of the human species and through the pressures of the natural environment, individuals of the species have developed certain common and stable biological characteristics—brain structures that are “responsible” for their social behaviors. At first glance, there might not seem to be anything problematic about this kind of evolutionary explanation. As long as this first reading is not also the last. We will give a specific example regarding recent findings in social neuroscience on schizophrenia:13

“The evidence shows that social cognition in cases of schizophrenia is responsive to educational-type interventions. Moreover, the impact of the neuropeptides oxytocin and vasopressin on social cognition has led to several attempts to use these neuropeptides in cases of schizophrenia to improve social cognitive difficulties. Additionally, it has been demonstrated that non-invasive brain stimulation techniques, such as tDCS (transcranial direct stimulation), can improve social cognition in healthy individuals, thus suggesting that non-invasive brain stimulation may be beneficial for individuals with schizophrenia in addressing their social cognitive difficulties.”

If schizophrenia is considered to be the result of a disorder of certain stable structures and functions of the brain, a deviation from a phylogenetically determined normality, then what else remains from interventions such as those suggested by the above excerpt? Only that if the issue ends there, then it is a kind of social theory at its worst, which not only explains nothing, but additionally conceals the explanation of deeper causes that may exist. Because schizophrenia is not a disease of all humanity, in all cultures, but mainly a disease of “advanced”, western-type societies. And a social theory that wants to claim that it explains social “phenomena” must explain, beyond the stable characteristics, also the differentiations, without necessarily reducing them to deviations from a normality. However, from this point onward, the next step must also be political, since every definition of normality necessarily involves political dimensions. A step that would certainly be suicidal for social neuroscientists, if it is assumed that they would have the disposition to take it: because careers, privileges and money would be at stake.

… inside a universe of machines

From a social and political perspective, however, it may prove that it ultimately matters little whether social neuroscience has the credentials to lead to deep insights into human social behaviors. In our view, it may turn out that the stake lies in changing these behaviors and social perceptions regarding the body, the mind, and their relationships, something that does not necessarily require cosmogonic philosophical changes. Towards which direction? Towards that which would treat the mind as yet another field of interventions, similar to those that medical practice and biological theory have managed to render self-evident for the rest of the body. Without being advocates of some dualistic separation between body and mind, it remains a fact nevertheless that such a separation has maintained some force in social perceptions even today. As a consequence of this somewhat privileged position held by the “mind,” such interventions are inevitably still met with certain minor social resistances or at least discomfort. It is indicative that, in the excerpts from neuroscientists we presented at the beginning of the article, the authors take care to remain, even if awkwardly and ungracefully, within the bounds of today’s political correctness, exorcising neural reductionism, at least in words.

A tactical move that perhaps won’t even be needed in a short time. Because capitalism does not remain static and especially in its current, hyper-technological form, it runs at speeds often incomprehensible at its technical level. And no matter how much some forms of “resistance” endure, whatever form they may have, they “owe” it to themselves to bend. In the new, post-human paradigm14, genetics has a crucial tool to offer: the ability to intervene even at the molecular structure level of the body. Neuroscience, on the other hand, is on that line of attack called to conquer a different but necessary ground for the smooth fusion of human and machine. That of constructing the appropriate interfaces. Precisely because of the centrality (rightly or wrongly) considered to be held by the brain and nervous system in processing environmental information, any narrow type of human-machine interface must pass through the nervous system. And the nervous system must in turn become understandable as a field of interventions, so that the corresponding technologies can proceed. But if it has already been accepted that consciousness resides in the brain and that it is nothing more than a computational machine, then who would dare raise objections and on what grounds? It would be nothing more than two machines talking to each other. A “simple” technical issue that would equally “simply” fall within the jurisdiction of engineers…

Separatrix

What is depicted here is the so-called connectome of the brain, that is, the map that shows which areas are connected to each other.

The reference to the genome is clear, and equally ambitious are the aspirations for its “decoding.”