The cyberspace did not leap fully armed from the head of the informatics Leviathan. It was constructed, developed, and infiltrated every field of human activity in a methodical and by no means “anarchic” way, despite the relevant philology that wants prophets, visionaries, and pioneers to play a central role in its formation. The first computer networks and the first attempts to fuse computing machines with their human operators resemble images of a primitive era. They resemble, but they are not; already from the early stages, when the construction of cyberspace was a matter of military laboratories and academic institutions within the framework of strategic planning, it had inscribed in its hard core, among other things, certain characteristics that remain unchanged to this day (and this is an issue we have repeatedly highlighted through these pages). We now know without any doubt whatsoever: what was being built then would not constitute a field of unlimited possibilities for human communication and creativity, but a mega-machine of manipulation and control aimed at subordinating social relations to the new bioinformatics paradigm.

Therefore, a crucial question for warfare in cyberspace is whether, already from the time when it was traversing its early stages of socialization and before it grew irreversibly, the hype could have been set aside and criticism could have focused clearly on the essence of this digital mechanism. This is not a philological question or an exercise in hypothetical scenarios: either the bioinformational restructuring and generalized digital intermediation are proceeding at such a speed that any confrontation with them is futile, or we must remain in a constant state of critical readiness to promptly anticipate developments. Moreover, social media, the Internet of Things, smart cities, or cyberwarfare are not the final, definitive stage of cyberspace. However, they can become…

1994 belongs to an era when cyberspace was still taking shape around the relatively recent construction of the internet. It had not yet been fully weaned from state support, nor had it been socialized to today’s explosive dimensions. The World Wide Web appeared in 1991, and the first browser in 1993. In the United States at that time, users numbered about half a million, and for reference, in Greece (among the late adopters, but not the most delayed), there were 200 users in 1992 (the year ITE introduced the internet) and only 4,000 by 1994.

humdog is probably a person you ignore. At that time, humdog was not a “pioneer,” that would be an inaccurate characterization, but literally a tracker of a new and largely unknown field, in which ideology had already managed to invest a plethora of mythological characteristics. She was one of the most active members of the online community The WELL, one of the earliest formations of the internet, within which the idea of the “digital utopia” and cyberspace as a tool for liberating communication was systematically cultivated. In 1994, although she had established herself as a significant figure in The WELL’s electronic forums, humdog, with her text “pandora’s vox: on community in cyberspace,” decided to break with her digital community. She was perhaps the first to clearly and sharply identify and expose the “dark” points of the supposed and much-advertised electronic utopia. She writes about the commercial dimension of cyberspace, its control by service providers and the control-censorship exercised by these companies over communication; about the commodification of human interaction; about the reproduction of divisions in the digital universe; about the central role of the white, middle-class and its ideology; about the voluntary surrender to policing. Even the examples she uses are characteristic, in light of how “communication” on the internet has evolved. Cases that were then, 25 years ago, novel and subject to harsh criticism, today constitute the definition of common practice in cyberspace, to the extent that paranoia and hysteria have become the leitmotiv of online “dialogue.”

Her critique does not exhaust what could already then be reasonable conclusions. She foresees that cyberspace is an attempt to invest representation with the gravity of reality; that the subjects that star are not people with their social relations and their interactions, but constructed identities, images, phantoms, in search of other such constructions for consumption; that fetishism and hysterical identifications are the norms that govern digital communication. She ultimately writes that despite the chatter, cyberspace is a place of silence and its language is a frozen language, thus echoing the sunbeams in the scorched city of a decade earlier: here, to “speak” you must deny yourself communication, and to “communicate” you must deny yourself speech…

As expected, the text of humdog caused a wave of angry reactions, since it directly challenged the ideology of digital utopia. Adopting her perspective required a fundamental intellectual “shake-up,” at a time when more and more people were choosing the easy comfort of electronic numbness; consequently, she was soon categorized among the “strange” and the marginal. However, the fact remains that, regardless of how little or lesser impact her view may have had, humdog’s opinion—whether we agree with it or not—nonetheless represents the kind of militant criticism that the biopolitical restructuration demands. And just as it was feasible 25 years ago, it is equally necessary today.

The voice of Pandora: for the community in cyberspace

by humdog (1994)

When I entered cyberspace, I went in thinking it was a place like any other place and that it would be a human interaction like any other human interaction. I was wrong to think that way; it was a terrible mistake.

The first time I realized it wasn’t a place like any other and that the interaction would be different was when people started addressing me as if I were a man. When they wrote about me in the third person, they said “he.” I found it interesting that there were people who thought of me as “he” instead of “she,” and so at first I said nothing. I smiled and let them think I was “he.” This went on for a while and it was funny, but after some time I started feeling uncomfortable. Eventually I told them that I, humdog, was a woman and not a man. They were surprised, and at that moment I realized that gender-based categorization was something that happened everywhere, and perhaps it was just very visible online.

I suspect that cyberspace exists because it is the purest manifestation of the mass as described by Jean Baudrillard. It is a black hole; it absorbs energy and personality and then re-emerges them as spectacle. People tend to imagine the mass as a virtual parade of hand-raising workers or wielding tools in their hands. However it may be, it is an image that draws its origin from Marx and is as romantic as a dozen red roses. The mass looks more like those faceless dolls you find in nostalgia-selling stores: limping, graceful, and silent. And when I say “graceful,” I include their macabre and laborious appearance in my definition.

It is fashionable to consider cyberspace somewhat like an island of the blessed, where people are free to satisfy and express their Individuality. Some people write about cyberspace as if it were a utopia of the ’60s. In reality, it is not true. Major online service providers, such as Compuserv and America on Line, systematically guide and censor dialogue. The differences have to do only with the method and degree. What concerns me, however, about this is that for the mass, the dialogue regarding freedom of expression exists only in terms related to whether you can or cannot say “fuck you” or look at sexual content photographs. I have a paradoxical perspective that makes me think that the discussion over the ability to write “fuck you” or the concern about the ability to look at photographs of sexual acts constitute The Smallest of the Problems surrounding freedom of expression.

Western society has a problem with appearance and reality. It insists on trying to separate the one from the other, to make the one more realistic than the other, to invest in the one with more meaning than the other. Nietzsche and Baudrillard have something to say about this. I mention their names in case someone thinks I’m making this up. Nietzsche believes that this dispute cannot be resolved. Baudrillard believes it has been resolved, and that is why some people think communities can be virtual: we prefer representation to reality. Image and representation exert tremendous power over culture. And it is this tension that runs through all discussions about the Real and the Non-Real, and contaminates cyberspace in all matters concerning identity, relationship, gender, dialogue, and community. Almost every discussion in cyberspace about cyberspace ends in some kind of opposition regarding “truth-in-packaging.”

Cyberspace is fundamentally a silent place. Within its silence, it is displayed as an expression of the masses. Someone might dispute the idea of silence in a place where millions of users’ digital identities parade around like angels of light, searching for whom they could, so to speak, consume. Silence is nevertheless present, and paradoxically present in the most deafening way at the moment when the user’s digital identity speaks. When a user identity posts something in a forum, it does so attached to the illusion that no one is present. Language in cyberspace is a frozen language.

I have seen people spill their guts online, and I did the same until I finally started to see that I was commodifying myself. Commodification means turning something into a product that has monetary value. In the 19th century, products were manufactured in factories, which Karl Marx called “means of production.” Capitalists owned the means of production, and goods were produced by workers under exploitative conditions. I was creating my inner thoughts as if I were the means of production for the company that owned the forum where I posted, and this product was sold to other commodified/consumer entities as entertainment. This means I was selling my soul as if it were a pair of athletic shoes, and I wasn’t even profiting from the sale of my soul [note: in 1994, The WELL had been acquired by the founder of an athletic shoe brand]. People who regularly post on forums seem to know they are factory equipment and athletic shoes, and sometimes they exchange messages about how their contributions aren’t recognized by management.

As if that weren’t enough, all my words had become immortal through copying into digital media. Even more so, I was paying two dollars an hour for the privilege of being commodified and displaying myself. Even worse, I was exposing myself to the risk of thorough scrutiny by such friendly types as those from the FBI: they can, and have already done so, download almost anything they fancy into their archives. The rhetoric in cyberspace is that of a language that liberates; the reality is that cyberspace is an increasingly effective tool of control with which people have a voluntary relationship.

Supporters of the so-called “cyber-communities” rarely focus on the economic, business nature of the community: many cyber-communities are businesses that rely on the commodification of human interaction. They promote their products by feeding hysterical identities and fetishism, just like the companies that sell us $200 athletic shoes. Cyber-community supporters avoid mentioning that these discussion forums are rarely characterized by cultural or national diversity, although they are quick to support precisely this idea. They rarely comment on the white, middle-class demographic characteristics of cyberspace, unless these demographics conflict with the social advancement of white middle-class women within the framework of orthodox, academic feminism.

The ideology of the electronic community seems to include three elements. First, the idea of the social; second, the ecological/green [eco-greenness]; and finally, the assumption that technology equals progress in a way that recalls 19th-century logic. Beneath the analysis, all these ideas culminate in forms of conformity.

As Baudrillard has put it, socialization is measured based on the extent of exposure to information, particularly exposure to the media. The social, by itself, is like a dinosaur: people are increasingly withdrawing into activities that have more and more to do with consumption than with anything else. So-called electronic communities encourage participation in fragmented, mostly silent micro-groups, which primarily engage in dialogues to self-congratulate. In other words, most people lurk and those who post, congratulate themselves.

Eco-green is a social concept related to making people feel good. What makes them feel good is that they lend a hand in order to limit the pollution of planet Earth by the industrialists of the second industrial revolution. It is a good and desirable feeling, especially in an era when futurologists are trying to figure out a way to explain to people three hundred years in the future about radioactive waste. Eco-green is also a way to repackage Calvinist values in more palatable forms. Americans are Calvinists, sorry to say. They can’t do anything about it: it came with the Mayflower.

I also believe that the idea of electronic community is a manifestation of the triumph of symbolic value. There is nothing happening in an electronic community that is not infected by symbolic value. If the electronic community were anything other than an exercise in symbolic value, then hacking identity—which has everything to do with superficial symbolism—would be much more difficult. Symbols that proclaim electronic technology “green” abound in cyberspace: the behavior of political correctness; the “green” computer; the digital office; the illusion that identity in cyberspace can be manipulated in order to overcome gender, nationality, and other emblems of cultural divisions (the last of which is, of course, simultaneously the most persistent and the most ridiculous). Both these concepts, the social and the ecological/green, are directly fed by an idea of progress that would not be out of place in a 19th-century industrialist.

I will give you an example: the WELL, a network forum of dialogue based in Sausalito, California, is often advertised as an example of a “social formation” in cyberspace. Initially part of the Point Foundation, which is associated with the Whole Earth Review and the Whole Earth Catalogues, the WELL occupies a notable corner of the electronic communities market. It advertises itself as a discussion network for educated, book-loving, and creative people. It self-advertises as a catalyst for political change, but it is in reality Calvinistic and somewhat more than “green.” The WELL is also imbued with an old-fashioned hippie aura that results in some notably sensitive ideas about society and culture. However, no one should fool themselves into thinking that the WELL differs in any way from large corporations such as America Online or Prodigy—all of these are service-providing businesses, and these services are owned by large corporations. It’s just that in the case of the WELL, due to a sluggish operating system, this is somewhat less obvious.

In July 1993, in a case covered by the national press, a man’s reputation was destroyed on the WELL by people from the WELL because he had dared to be involved with more than one woman at the same time; and because he did not conform to the social protocol of the WELL. I won’t say that he didn’t conform to moral criteria, because I believe that the ethics of honesty in cyberspace are such that sometimes they render the word “moral” meaningless. In cyberspace, for example, identity can be a work of art. But the issues that emerged within this topic, under the name News 1290 (now archived), were extremely complex and directly revealed the heart of the cyberspace problem: the desire to invest representation with the weight of reality.

The women involved in “case 1290” became recipients of a man’s interest on multiple levels: most importantly, they believed in the reality of the symbols he projected and invested them with meaning. They made love with his symbols, and there is no doubt that this relationship affected them and that they felt pain and unhappiness when it ended badly. At the same time, it appears that the man in question did not invest his own symbols with the same meaning that the women had invested in his, and it is also clear that all parties had not had any discussion about how each interpreted the other. Consequently, the non-communication that took place was attributed to the exploitation of the women by the man with whom they had been involved, and the conclusion drawn was that he had used them as sexual objects. The women, for their part, felt comfortable with the role of victim, and so the game began. Of the hundreds of voices heard on the subject, very few were sharp enough to support the idea that the events had actually been caused more by the media than by the individuals who had suffered the consequences of the events. People with this perspective supported the idea that crucial elements were missing, such as body language, tone of voice, and natural presentation. None of these, they argued, exist in cyberspace, and therefore people construct unrealistic representations of the Other. Nevertheless, such opinions were in the minority. Most people ended up with proposals that would have shocked the organizers of the Terror [during the French Revolution]. Even words like “criminal thought” were used, while proposals for lynching were not lacking.

Hysterical identification is a psychological mechanism that allows a person to take on the sufferings of others. Until the 1880s, it was considered a women’s problem. In our society, many decisions about who someone is are made through the mechanism of hysterical identification. In many cases, this is achieved through the miracle of commercial advertising, which invests products with magical properties, turning them into fetishes. Buy the fetish, and the identification promised by the advertisement will become yours. It is convenient, easy, and requires no other investment except money.

In October 1994, topic 163 opened with the theme of couples. In this topic, user Z appeared in order to discuss the problems of her married life, which included a daughter who was psychologically disturbed. The discussion started in the most common way for such issues, with the woman asking for and receiving advice on what to do. Within a few days, however, the situation escalated and the woman added yet another voice to the discussion, supposedly that of her daughter X. The alleged daughter exposed her problems and expressed her feelings about them, and the problems seemed to be threatening her own life. This appears to have triggered something uncontrollable within the discussion and a real orgy began as voices started to appear expressing their identification with the mysterious and troubled daughter X. The nature of the identification and the tone of the posts became increasingly bizarre, until user Z threw the final frightening pebble into the whole situation, posting a distorted lyrical monologue about maternal comfort and affection towards the virtual Inner Child who apparently had found refuge in her tender and protective embrace. The more the Inner Child mourned, the more the Virtual Mommy poeticized the situation and offered comfort. This spectacle, which horrified many trained mental health professionals who read it on the WELL, continued for many days and was discussed extensively in many instances and in suspicious tones. When the topic reached a breaking point, the Virtual Mommy withdrew reluctantly, insisting that only a barbarian would believe she would exploit her own tragedy for personal gain.

One of the interesting issues regarding both cases, for me, is that they were deleted from the discussions. The “news1290” exists in the archive. This means it has been archived in an electronic filing cabinet, much like the Vatican did with the transcripts of Galileo’s trial. It exists, but you have to search for it and the 1290 reference makes people at the WELL nervous. The “couples 163” was cleared and doesn’t exist in any form, except for backups on hard drives of individuals (like me) who downloaded it for their own reasons. What I identify here is that the electronic community aligns perfectly with the society’s growing trend of dehumanization: it wants to commodify human interaction and enjoy the spectacle, regardless of human cost. If and when the spectacle proves uncomfortable or dangerous, it engages in creative historiography, like any good banana republic.

However, this should surprise no one. Aesthetically, the electronic community of the kind exhibited by the mild, new-age type contains equally both elements of modernism – resistance to depth and fascination with surface – combined with the postmodern aesthetic of fragmentation. The electronic community leaves behind permanent records that are open to exhaustive scrutiny, while simultaneously maintaining an illusion of transience. In this way, it manages to somehow satisfy the needs of both the Orwellian and the psycho-archaeologist.

People can talk about cyberspace as if it were a utopian community, simply and only because it is a literary construction and as such is subject to syntactic revisions. The two previous topics, plus another where a woman’s death was choreographed as an online spectacle, made me think about what the electronic community is, and how it probably doesn’t really exist, except only as a kind of marketplace for the consumption of symbolic values.

More and more, consumption becomes an object of micro-management, as Alvin and Heidi Toffler explained, speaking about “de-massification.” The self-proclaimed electronic community can be seen as a kind of social micro-marketing for a self-anointed elite. This condition excludes the possibility of human relationship, from which all authentic communities begin. If someone exists merely as symbolic value, as an empty letter, as a limited subset, then of course it is absolutely appropriate to speak of a community of symbols, nicely arranged, categorized, recorded, and ready for consumption.

Many times in cyberspace I felt the need to declare that I am human. Once, I was told that I basically exist as a voice in someone’s head. Many times I needed to see someone’s writing on paper, or a photograph, or have a phone conversation in order to confirm the human dimension of the voice, but that is the way I am. I resist being categorized and recorded, and I take William Gibson seriously when he writes about artificial intelligence and structures. I don’t like such things. I suspect that my words have been taken out of context, and when this text is published, they will be taken even more out of context. When I left cyberspace, I left one day early in the morning and forgot to take out the trash. I spoke with two friends later on the phone, and they told me that anyway, my address with my posts is still there. And they knew, as I knew, that it was possible for people to continue to be entertained by the contents of my address. Entertainment never ends, as Peter Gabriel wrote. Perhaps someday I will return to complain again, if something interesting comes up. Meanwhile, give my love to the FBI.

at the intersection of virtual and real world

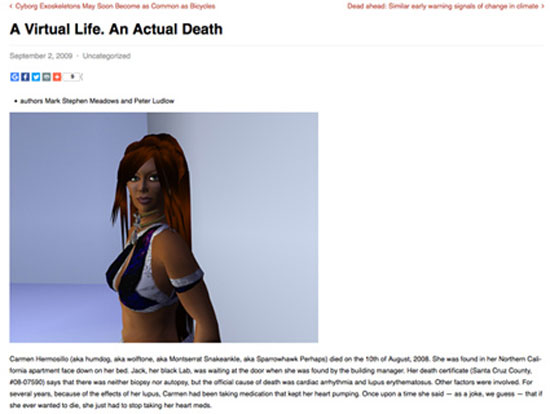

Humdog was the pseudonym of Carmen Hermosillo – author, essayist and poet among other things – with activity in cyberspace from when the internet had not even acquired its name. Her decision to suspend her online activity was not definitive, but every time she resumed participation in chat rooms and forums (basic forms of the internet then), her presence had explosive properties. Her attempt to strip the “digital utopia” of its false characteristics was unforgivable and the attacks from nerds and “pioneers” were relentless.

Her life itself had a dimension of tragic irony, since what she constantly warned against was the very thing that eventually destroyed her. In the final years of her life, humdog (or wolftone, or Montserrat Snakeankle, or Sparrowhawk Perhaps, as she was known by some of her other avatars) had “plunged” into the virtual world of Second Life. Her experience there was divided. On one hand, with the help of friends and collaborators, she had constructed an incredibly detailed medieval French city inhabited by a multitude of other avatars, engaged in an intricate role-playing game. She had written at length about this aspect of her experience in the book “I, Avatar.” On the other hand, Hermosillo had been absorbed by another extensive community within Second Life, called Gor—a community inspired by the eponymous fantasy book series centered on a planet where sexual slavery is institutionalized and widespread. There, humdog found herself alongside her partner (a relationship that began virtually and extended into the real world) and ultimately became his virtual slave. She was not unaware of the pathetic nature of her position and even documented her experience in detail in the essay “Confessions of a Gorean Slave,” writing there that it would not be long before suicides begin due to events and relationships in the virtual worlds of Second Life. She had gone so far as to set up a virtual “therapy center,” paying a psychologist out of her own pocket to help the “slaves” (some of whom could very well be men in the real world).

However, no matter how much wit and critical ability someone may display, the journey from a French city’s replica to a world of institutionalized sexual slavery is a spiral descent into the abyss. At some point, her virtual “friend” disappeared and abandoned her. Shortly afterward, humdog began deleting all her electronic accounts and was ultimately found dead in her home on August 10, 2008, having stopped taking her necessary heart medication days earlier. A virtual life that ended in an ordinary death.

Harry Tuttle