“In the event that intense climate change phenomena occur, that is, an average global temperature increase of 2.6 degrees Celsius by 2040, then large-scale non-linear environmental events will cause large-scale non-linear social events. In this scenario, the magnitude of the changes and their catastrophic consequences, such as pandemics, will bring nations around the world to a point of suffocation. Their internal cohesion, even in the case of the U.S.A., will be put to the test, both as a result of a dramatic increase in migration and due to changes in agricultural practices and water availability. Coastal floods worldwide, especially in the Netherlands, the U.S.A., southern Asia, and China, may create cracks in local and national identity. Armed conflicts between nations over access to natural resources, such as the Nile and its tributaries, cannot be ruled out; even nuclear war is possible. The spectrum of social consequences ranges from the rise of religious fanaticism to absolute chaos. Based on this scenario, climate change will bring about a permanent change in the relationship between humans and nature.”

Where does the above excerpt come from? Various kinds of ecological organizations would be an easy guess. Or perhaps some green party. It would even fit organizations of the extra-parliamentary left. If we told you it belongs to one of the Greek parties, could you, with some, even slight, certainty, tell which one it is? Difficult. In any case, the answer lies on the other side of the Atlantic and concerns a 2007 report co-signed by the Center for Strategic and International Studies and the Center for a New American Security,1 both think tanks specializing in geopolitical analyses and closely linked to the U.S. military-police complex. This little quiz is enough for one to understand the extent to which climate change rhetoric has permeated the thinking of citizens in Western societies. Climate change now constitutes a self-evident fact (roughly like the fact that the Earth is round) which anyone can (but also should) adopt as such. The political space to which someone belongs seems almost irrelevant in the face of such an existential threat—although it is more convenient to belong to the liberal (whether right- or left-leaning) and “sensitive” middle classes of the West; the “fight” against climate change helps one sleep at night.

The reality of course is slightly more complex than the simplistic scheme that starts from your car’s broken catalyst and ends with the collapse of human civilization within the next few decades. It is a fact that among scientists there is a strong majority consensus regarding both the existence of climate change, that is, the increase in global average temperature, and its causes, which are attributed to increased levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere due to the burning of fossil fuels. The consensus is majority, but not absolute. Objections have from time to time been raised against all the links in the chain of reasoning that starts from pollutant emissions and leads to global temperature increase. Even the “simple” measurement of global temperature does not always have the necessary reliability one would expect, since it is not naturally a measurement but a weighted calculation that extends both spatially, across the entire planet, and temporally, throughout the course of a year, with all the uncertainties such calculations entail. When such measurements refer to previous centuries, when they must be made indirectly (e.g., through the rings formed by tree trunks), then the range of uncertainty increases even further, especially when we are talking about temperature variations of the order of half a degree Celsius – approximately the amount by which temperature increase is estimated compared to the pre-industrial era. The discussion becomes even more complicated when it comes to the issue of causal (or non-causal) relationship between carbon dioxide levels and temperature. Here we no longer speak of measurements and experimental results, but of mathematical and computational models based on specific assumptions, such as, for example, that an increase in carbon dioxide also brings about an increase in water vapor, which is the atmospheric component that actually leads to temperature increase. Moreover, such models have the problem that they are not easy to verify or falsify, except in a highly simplified form.

We neither have the ability nor the inclination to follow the relevant scientific discussion in all its details. There are, however, certain disagreements that are hard to overlook, even if one starts by accepting the increase in temperature and its human causes as given. If climate change is considered something certain, what is by no means certain are its consequences, which lie beyond the predictive capabilities of any computational model. Contrary to any apocalyptic scenarios, it is by no means obvious that the outcome would be some kind of ecosystem collapse, a hell-inspired inferno with endless fires around the equator and permanent floods across larger geographical latitudes. Equally convincingly, one could support the scenario of the planet returning to temperatures particularly favorable for the further expansion of rich and dense forests, as was indeed the case during the age of dinosaurs when temperatures were significantly higher than today’s. The disagreements in the discussion about climate change become even more apparent when it shifts to socio-political issues, as in the excerpt we started with. When behind the guise of scientific-type “objectivity” the entire arsenal of a revelatory horror is mobilized, featuring diseases, wars, and the collapse of entire states, then one is justified in suspecting that the above-mentioned (is there any other?) management of the climate change issue at an ideological level carries the metaphysical flavor of a quasi-religious delusion. Much like in the most recent case of artificial intelligence and the terrifying threats under which it is supposedly going to place humanity, from job elimination to complete human extinction (the same scenario again, what a coincidence!). Or, as was fashionable a few decades ago, similar to the scenarios of a global nuclear war. The difference being that the anti-nuclear movements had indeed started from the grassroots, and that the dystopian scenario of the time did not concern some overheating, but the opposite: the probability of a nuclear winter, as a result of using atomic weapons. Times change (metaphorically speaking…), but so do fashions.

The interesting thing here is that the relevant research on climate change was available from then on, but no one seemed to care. The nuclear winter dominated the media and the minds of citizens. As early as 1967, the first articles had appeared in reputable scientific journals predicting an increase in global temperature by two degrees Celsius in the event of a doubling of carbon dioxide levels. Similar articles were also published in the following decades of the 70s and 80s, without any significant difference compared to today in terms of the type and accuracy of their predictions. No significant methodological change intervened in the meantime, nor were new data made available that would alter the results of previous research. Nevertheless, during the Cold War, global warming remained on the margins of attention.

A turning point in the ideological management of the “climate change” issue appears to have been the early 1990s, when, under the auspices of the UN (does anyone even remember this organization still exists?), the first large-scale conferences began to be organized for the planet’s salvation, most notably the 1992 Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro. It is worth noting here that these conferences were not prompted by pressure from environmental movements. On the contrary, they were a series of top-down initiatives, with some of the figures involved hardly being beyond ecological suspicion (such as Maurice Strong, an oil executive by profession, yet also a pioneer in the fight against climate change). Among other things, a stated goal of the Earth Summit was “to revitalize international cooperation on development issues after the end of the Cold War.” 2

In our assessment, and to put it less elegantly, the issue that urgently needed to be resolved after the collapse of the Soviet Union was the management (and plunder) of the remnants it left behind, as well as the rapid integration of large parts of it into global capitalist norms. For this endeavor to have a “happy” outcome, it first needed to be dressed in new ideas and lofty ideals, which of course had to be exported by the West. After the “collapse of the grand narratives,” the project of civilizing the “barbarians” (once again) had to disguise itself in a new version. One expression of this disguise went under the name “discovery of Islamic terrorism,” which became the primary legitimizing mechanism for the ongoing oil wars from then until today, right in the belly of the former Soviet Union. The other side of this disguise, the one with a more alternative persona, would be dressed in the green colors of climate change 3. Especially for the middle classes, who over time would realize that their position in the social pyramid was far from secure (a development that had already begun to emerge in the ’70s with the stagnation of real wages), the boogeyman of terrorism (for their right wing) and the specter of climate change (for the more liberal) would be called upon to function as the new great enemies, the Kavafian barbarians who would give some meaning to their struggles as well as an exit.

Apparently, the fight against climate change and the war for oil seem to have diametrically opposed goals. This raises a paradox. How is it possible for countries with the most voracious appetites and dispositions for oil to simultaneously champion (especially European ones) climate change resolutions and fund relevant organizations? This is a paradox only if one has a somewhat simplistic idea of the energy model of capitalism after the second industrial revolution and especially after the end of the Second World War. This model was indeed based largely on fossil fuels in general and more specifically on oil. As expected, the capitalist formations that were articulated around it had (and still have) every reason to impose controls on the flow of energy resources. However, we should clarify what is meant when we talk about “oil control.” Initially, of course, it must mean uninterrupted access to these resources by leading capitalist powers. A characteristic example of such a case is the post-war agreement between the U.S.A., the sole victor of WWII,4 and Saudi Arabia, which secured for the former access to what they considered strategically important oil reserves and for the latter the preservation of the Saud family in power and generous military aid.

However, unrestricted access does not necessarily mean unsanctioned production. On the contrary, depending on geopolitical conditions, oil reserve controls may include creating scarcity. For various reasons, some of which are obvious. The direct or indirect exclusion of competitive blocks from energy resources is one such reason. Another reason, not so obvious, but of great significance, is monetary and relates to the de facto primacy of the dollar as the global currency of trade transactions. As is known, it was the Bretton Woods agreement, which the U.S. imposed immediately after the end of World War II, that allowed the dollar to acquire this privileged position. In this way, for every transaction made in dollars, the American economy manages to extract a “seigniorage” and maintain an inexhaustible “credit” line, as long as the demand for dollars remains high. The “problem” with the Bretton Woods agreement was that it ultimately proved overly successful. With the stability it brought to international transactions, it allowed economies devastated by the war to get back on their feet and gradually become competitive even against that of the U.S. With the American economy entering the early 1970s in a prolonged period of trade deficits (which continues even today) and its needs for military equipment growing (see Vietnam War), Bretton Woods was now a burden. Since it was required, based on the agreement, to guarantee the conversion of dollars into gold, it was unable to extend this “credit” line in order to sustain its deficits and its monstrous military apparatus. It managed to rid itself of this burden simply by cutting the Gordian knot: it unilaterally and without warning withdrew from the agreement, thus freeing the dollar from gold.

Such a bold move, however, carried risks for the dollar’s monetary sovereignty. To protect the dollar and maintain high demand for it, it needed to be tied to something equally strong as gold. This “something” that met the specifications of global circulation and high demand was, of course, black gold 5. Unlike gold, however, oil’s value is subject to fluctuations, since it is a commodity “like all others.” A significant drop in its price (as with the price of any other commodity priced in dollars), for example due to overproduction, would consequently result in a decrease in demand for dollars. As one can understand, such a thing naturally could not be allowed and oil could not become a commodity “like all others.” Mechanisms and strategies for controlling its production and distribution in global markets are needed. When Asia’s oil reserves were “liberated” after the collapse of the Soviet Union, they could not be left to chance and in the hands of competitors of the U.S., both for geopolitical and monetary reasons. We all know what followed, but a note is needed. The successive U.S. campaigns in Iraq and Afghanistan did not bring an oil flood to global markets. We repeat: controlling oil requires much finer balances compared to what a simplistic perception would expect and often aims at creating scarcity.

The discussion on climate change is doomed to remain desperately naive if it cannot be integrated into its geopolitical context and if the joints connecting it to capitalism’s energy model and any potential changes to it cannot be mapped. Whoever believes that the minds of Western citizens, otherwise deeply hypnotized and opiated, woke up one morning with ecological sensitivities probably also believes that in Greek football – the best kicker wins – and that championships have nothing to do with changes in power correlations among owners – gangs. The outbreak of interest in climate change – an interest directed from above – in the early 1990s should therefore not be considered unrelated to the broader geopolitical realignments of that era. In our opinion, some factors that contributed to the increase in interest are the following:

– The collapse of the Soviet Union created an ideological vacuum that needed to be filled. Climate change had the advantage of being a sufficiently vague enemy, largely controllable in terms of its management, but also global so that it could be invoked as needed and according to circumstances.

– A way had to be found to control Asia’s oil reserves, not always in the direction of overproduction, but also in the opposite direction of underproduction. Climate change could also function here as an ideological pretext for limiting the use of oil and minerals.

– A possible awareness on the part of elites – regardless of any climate change – that fossil fuel reserves are indeed finite and that in the long run, at least a partial change in the energy model would be required, was perhaps another factor that initiated the change in attitude towards fossil fuels 6. An attitude change that required the “consumer public” to be convinced with the appropriate ideological massage, especially since the development of new technologies usually involves high costs.

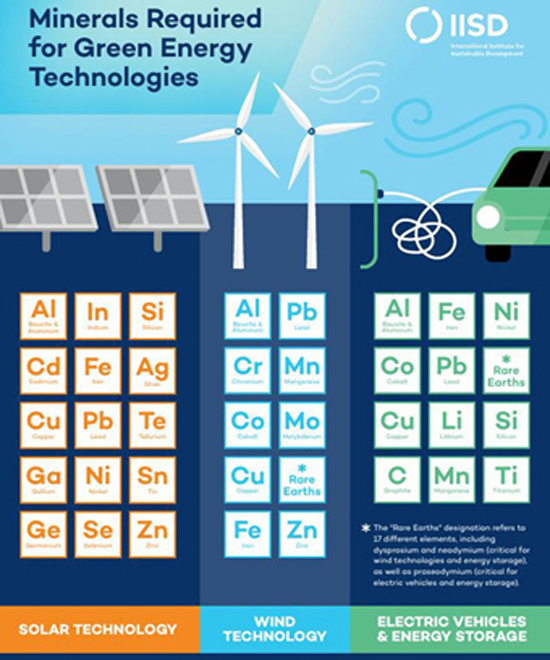

– Oil and fossil fuel reserves, despite the well-intentioned efforts of Western states, are not entirely in their hands. There were and still are significant reserves beyond their control capabilities, something that obviously provides significant maneuvering possibilities to their competitors. The rise of the Chinese economy that began in the 1990s was initially fueled by fossil fuels and based on old, widespread, and relatively easy extraction and processing technologies. Green technologies, being even more capital-intensive but also “material-intensive,” 7 had the ability to give a relative advantage to Western countries that developed them (and we say “had” because China now leads in this area too) and to function as a counter-pressure lever against countries that dared to demand development in an anti-ecological way.

– It is not rare for similar geopolitical frictions to appear even among developed states. For example, in contrast to the U.S., European countries, not having significant reserves of their own and without the military weight that would ensure them relatively trouble-free access to such reserves, show greater interest in transitioning to a more “ecological” energy model. As a result, their sensitivities towards ecological issues, such as climate change, even if they contain a grain of truth, are influenced and fed to a significant extent by such harsh and extremely capitalist calculations.

The above “cynical” observations are not intended to lead to the conclusion that the phenomenon of climate change is non-existent and therefore there is no reason for concern. It is not our intention to rinse the existing energy model of capitalism. However, the appropriation of ecological concerns in order to manage them from above safely can turn (if it has not already) ecological movements into yet another pawn on the geopolitical chessboard. Climate change proves to be one of the best candidates for such an intervention in ecological movements. Not only because of the inherent uncertainty regarding its results and the way to deal with it, but also because it must first be mediated by experts. Even if the predictions of mathematical models are correct, there is still a matter of interpreting them until they reach the non-specialized public. To put it in a “simplistic” question: if in a few years studies emerge that cast doubt on the so far conclusions about climate change, in what exact position will ecological movements find themselves, since they have placed their greatest weight on this issue? Will they self-destruct? It should be noted here that such a development would not be an exaggerated scenario. Since the American economy has fallen behind the Chinese in the race for renewable energy sources, both in raw materials and investments,8 while at the same time it has risen to first place in oil extraction, perhaps the time is not far off when it will start to feel uncomfortable with promises to limit carbon dioxide emissions (Trump has already given the first samples); hence it will have to find a way to change the “narrative,” even by commissioning convenient research for itself.

Therefore, choosing climate change, out of all the ecological disasters that have accumulated on the planet over two centuries of capitalist development, to place it at the center, rather than being one front of critique among others, ultimately seems very convenient in facilitating the transition to a new energy model, whenever and to whatever extent this is deemed necessary. If this is recognized as the quintessential ecological problem and if behind the term “anthropogenic causes” it essentially implies a technological inadequacy of today’s energy model, then there remains no room for discussion regarding the solution. It is offered ready-made, in the form of more, smarter, more efficient, and greener technology. With a small caveat. It might eventually prove that “green” technologies are not so ecological after all. We have already mentioned it. Being far more material-intensive, the ecological footprint they leave behind is disproportionately large due to the energy required for the extraction of these materials, without yet fully understanding the extent of the impacts from direct environmental contamination caused at the extraction sites 9. And of course, it would be naive to expect that geopolitical conflicts over access to the essential raw materials for new technologies will cease, especially given their geographical distribution which places the largest reserves outside Western countries (with the exception of Australia) 10. The likelihood of such developments should only surprise those “ecologically sensitive” souls who ultimately hope for a capitalism with a green face, just as a few years ago it was fashionable to speak of capitalism with a human face. Behind the facades, however, capitalism has a face; and that face is anthropophagous and ecocidal.

Separatrix

- The title of it is “The Age of Consequences: The Foreign Policy and National Security Implications of Global Climate Change”. ↩︎

- For details, see the report by Denis Rancourt, «Geo-economics and geo-politics drive successive eras of predatory globalization and social engineering». ↩︎

- But not only that. Techno-fetishism towards new technologies played a similar role, starting from the fans of the Whole Earth Catalog in the late 1960s and reaching a point of climax with the spread of personal computers and especially with the spread of the internet, from the 1990s onwards. ↩︎

- In 1951, with the “mutual defence agreement” the USA undertook to provide weapons and training to Saudi Arabia in exchange for the smooth supply of oil. ↩︎

- Oil is not the only commodity that imparts value and demand to the American dollar. Another such “commodity” is opium. Not coincidentally, the prolonged wars in which the U.S. has been involved in Vietnam and Afghanistan have made these regions the world’s largest producers of opium. ↩︎

- Many oil companies are at the forefront of developing technologies for renewable energy sources. They do not wait passively for their death. ↩︎

- We copy from the 2017 World Bank report titled “The Growing Role of Minerals and Metals for a Low Carbon Future”: “The report clearly shows that the technologies considered to be at the forefront of the shift towards clean energy forms – wind and solar systems as well as hydrogen and electricity systems – are in reality significantly MORE material intensive in their composition compared to traditional energy systems based on fossil fuels.” ↩︎

- See the World Bank report for data on material reserves, such as rare earths and other metals, as well as the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) report “The Geopolitics of Renewable Energy” (2017) for the scale of investments. In 2015, Chinese investments in renewable energy sources exceeded 8 billion dollars (by far in first place), with the U.S. at 3.8 billion. ↩︎

- For example, some recent studies show that maintaining a used, gasoline-powered car that has a good ratio of kilometers per liter of gasoline proves ultimately more environmentally friendly than replacing it with a new electric car, precisely due to the enormous environmental cost of manufacturing the latter. As another example of environmental destruction caused by green technologies, let us recall the recent fires in the Amazon which some linked to intense agricultural activity in the region for the production of… biofuels. ↩︎

- See the report by the International Institute for Sustainable Development “Green Conflict Minerals: the fuels of conflict in the transition to a low-carbon economy” (2018). ↩︎