How the tools built for the U.S. census fueled the Nazi genocide, concentration camps, and state racism—and helped launch the digital age.

On a frozen December day in 1896, an American inventor was rushing to catch a train outside the Russian city of St. Petersburg. He wore a fur cap and a heavy coat with a huge collar that buttoned up to his ears. It covered his mouth and his thick mustache, leaving only a small part of his face visible to the outside world.

Hollerith was a hypochondriac who preferred to stay at home with his wife and mother-in-law, busy with his inventions. He hated traveling and hated traveling in Europe even more. Like an early version of a technology guru, he was obsessed with efficiency and mocked the locals for their attachment to ancient traditions that wasted time. “They live exactly as they did thousands of years ago,” he wrote to his wife from Italy. “I saw them cutting wood in the street from Naples to Pompeii, and when I reached Pompeii, I found frescoes depicting exactly the same way of cutting wood.”

Despite his reluctance to travel, the inventor had come a long way in life. Hollerith was only 36 years old, raised by his widowed mother in a humble house in New York, and yet he had just spent weeks mingling with aristocrats of one of the world’s most mythical royal dynasties. And now he was returning to his homeland with a lucrative contract for his new business ventures.

A few years earlier, Russian Tsar Nicholas II had issued an imperial decree ordering his ministers to complete the first census throughout the country. With the final deadline of 1897 approaching, they were racing against time. They knew they had a monumental task ahead of them – and one that was perhaps impossible to accomplish.

The Russian Empire had a population estimated between 100 and 200 million people, a range that explains why the tsar needed a census. The country stretched from Europe all the way across Asia, an area almost three times the size of the United States. To count all these people, census takers would need to travel to extremely isolated areas and question people in dozens of dialects. And problems were already brewing. Muslim Tatar communities in southern Russia saw the planned count as a secret tsarist conspiracy aimed at converting them to Christianity, while some Orthodox sects viewed the census as a sign of the antichrist and swore they would burn alive rather than submit to such blasphemy.

Conducting the census was only half the job. The data would need to be organized and analyzed. The tsar wanted the census conducted using the most modern methods – to include information about age, education level, gender, nationality, place of birth, residence, and employment. It was every bureaucrat’s worst nightmare.

The census officials knew that the only way to finish the job within a reasonable timeframe would be to use the most advanced technology available on the market. And this is where 36-year-old Hollerith enters the story.

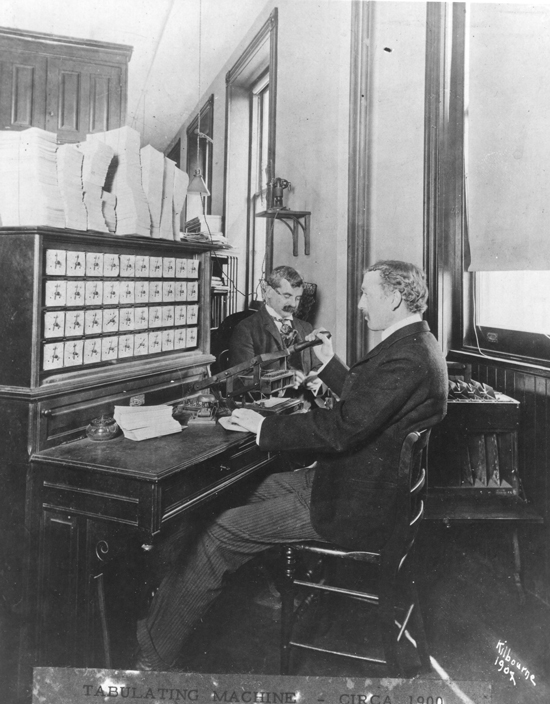

A few years earlier, while working for the American census office, Hollerith had developed the first mass-produced operational computer: the Hollerith tabulating machine. An electromechanical device, the size of a large office, that used punched cards and a clever arrangement of gears, selectors and electrical contacts, which processed data with amazing speed and accuracy. Work that previously took years to complete by hand, could now be finished in a few months. As an American newspaper described it, “with the help of the machine, 15 ladies are enough to count half a million people per day”.

Russia was not the only country that had shown interest in Hollerith’s computing technology. He had established his headquarters in New York a few years earlier, but had already become known among the highest circles of bureaucrats around the world. Canada, Germany and Norway were eager to rent his machines, while a company in Austria was trying piratically to copy the designs and offer them to European governments at a lower price.

Hollerith’s tabulating machines could work with any kind of data and be integrated into the organizational chart of any business that had information at the center of its operations. Railroad and insurance companies lined up outside Hollerith’s door to acquire machines customized to their needs.

Hollerith’s invention had caught the pulse of the second industrial revolution—a time of rapid automation and mechanization. It was the era of railroads, massive steamships, the telegraph, radio, electricity, large factories, and unprecedented real-time international communications. Coastal and railroad scheduling programs, complex banking data, actuarial tables, social security programs, government budgets—all were expanding at a rate greater than humans could keep up with. Information was king, and data processing was in constant demand.

In just a few years, Hollerith had become the extremely wealthy owner of a company that would launch the American computer industry. A few decades after his return from Russia, his technology would form the backbone of International Business Machines, or IBM—the global giant that for nearly a century would become synonymous with information processing and computer technology. Under the IBM banner, Hollerith’s technology would power governments, armies, and businesses around the world, crunch numbers throughout the Cold War, and persist until the dawn of the internet age. The world didn’t just use Hollerith’s tabulating machines—it became addicted to them and was transformed by them.

Hollerith was hailed as a genius. Many believed his invention was part of a larger data-driven technological revolution that would lead to a better, more efficient, and more harmonious world. A leading American statistician had predicted it would lead to an era of “global justice” and “make world wars impossible.”

Yet, despite all the utopian talk about Hollerith’s computers, information technology has dark roots.

the dream of “Make America Great Again”

The census in the US – which the constitution mandates to be conducted every ten years – is back in the news not only because it is scheduled to take place in 2020, but also because, as has often happened in the past, the census is a political issue with inevitable racial dimensions.

The current lawsuit concerns a plan devised by Trump’s former adviser Steve Bannon, to include a question about citizenship in the 2020 census. On the surface, it seems to be a minor detail. But there is a strong argument that this addition will have heavy political consequences for the entire next decade. (…)

A careful reading of the proposal by the Department of Commerce [note: the American constitution stipulates that the census be conducted by this particular department] to add this specific question, shows that the Trump administration wants to use the census to construct a first-of-its-kind registry for the entire US population – a decision that overtly exceeds the legal boundaries of the census. (…) Given the current administration’s hostile stance towards immigration, the fact that it wants to build a detailed database regarding nationality is extremely worrying. (…)

Whatever the courts ultimately decide, the latest dispute over the census is nothing new. For most of its history, the census—and the bureaucracy defined by the constitution that conducts it—has been intertwined with nativism, religious prejudice, and fear of the “other.”

The dark and ugly history of the census makes it a revealing witness to racial politics in the United States. The fact that the census simultaneously played a central role in the emergence of the information age 130 years ago is not unrelated and reveals how computers, mass surveillance, and racist policies were connected from the very beginning.

counting for democracy

Governments have been counting their citizens since the beginning of recorded history. There are descriptions of censuses in the Old Testament, on Sumerian tablets, and in the writings of ancient Greeks. Censuses were conducted systematically in Europe before modern times, and the American colonies also kept records of the population. Governments counted the population for two basic reasons: to increase state revenues and to declare war. They needed to know who and what they could tax, and they also needed to know how many military-age men could be called to arms. It was the American Constitution that added a third, and more modern, reason for counting people: representative democracy.

When the founders of the American system of government met in Philadelphia in 1787, one of the first things they established was a clause requiring a population census every ten years. The directive for the census appears at the beginning of the Constitution, even before the structure of government. For the Constitution’s drafters, the census came first because it would determine taxation and the balance of political power in Congress. According to the Constitution, the number of seats each state has in the House of Representatives is proportional to its population, which meant that the government needed to know the exact size of each state’s population.

The first census was conducted in 1790 and was overseen by Thomas Jefferson, who at the time served as Secretary of State. It was essentially a simple headcount, designed to barely meet the constitutional mandate. The entire process was expected to be completed in less than nine months. But despite its simplicity and the very small population, it took nearly two years to finish. From then on, things got worse.

With each passing decade, the census took longer and longer to complete. It was full of errors and faulty population estimates, a situation that led to major scandals and serious accusations that the data was being cooked for political purposes. By the end of the 19th century, bureaucratic problems had rendered the process useless: the census took almost ten years to complete, meaning the results were already outdated before they were even finished.

When the first census took place, 3.9 million people lived in 13 states. By 1890, the United States had expanded to 42 states and had a population of 63 million—a sixteenfold increase in population over the course of a century. Never before had a country expanded so much in such a short period of time. Census employees—who still worked in traditional ways, with paper and pencil—struggled to keep up; they were drowning in data.

Meanwhile, in addition to having to count a rapidly growing population, governments began to burden the census with more and more questions: about employment, illiteracy, crime, health, homeownership, economic trends; as well as racial and immigration status with increasing detail. As the 19th century drew to a close, census officials had begun to transform what should have been a simple population count into a system of racial surveillance.

anglo-american supremacy

It was a different country then: smaller and largely rural, but rapidly expanding westward. The Civil War had ended, and the American army had turned to pursuing and exterminating Native Americans west of the Mississippi. Transcontinental railroads were connecting vast stretches of the country—eliminating time and distance and shifting economic power to the new business elite of banks and railroads. The country’s demographics, as well as racial policies, were also changing rapidly.

Slavery had been abolished, allowing millions of Black people to move freely, to try to take their chances into their own hands, and to play a greater role in political life. Migration was also intense. In the first half of the 19th century, free migration to the U.S. was primarily dominated by English settlers. But from 1850, the trend began to change dramatically. Millions of Irish peasants arrived in the country to escape famine. Millions of others were fleeing the crushing poverty of southern Italy and eastern regions of the Russian Empire. Chinese workers arrived in large numbers on the western coast to work on railroad construction.

The stream of immigrants was a blessing for the rising industrial oligarchy, as an inexhaustible source of cheap labor. But it was also a source of political instability. Deep inequality and exploitation led to mass movements demanding change. (…) The American political establishment viewed this upheaval with fear. In the masses of unfree blacks and Chinese, Jewish, Irish and Italian immigrants, with their strange languages, unknown religions, and their demands for a better life and political rights, they saw a threat.

Looking for a solution to grab onto, many found comfort in the quackery of pseudo-scientific racial theory, in its various versions. The so-called social Darwinists used a distorted version of the theory of evolution to explain why the poor and marginalized should remain as such, while the rich and successful deserved to exercise power without any challenge. Taking this theory a step further, supporters of eugenics fanatically believed that the natural superiority of Anglo-Americans was on the verge of extinction due to the hyper-fertility of the “degenerate” and immigrants. To avert this threat, they advocated the application of strict controls on reproduction and its regulation aimed at “quality,” in the same way that breeders do with horses and cattle.

These ideas were not marginal at all, but were openly and intensely supported by the cultural and political mainstream. In the circle ranging from future presidents such as Roosevelt, Hoover and Coolidge, to wealthy barons such as J. P. Morgan and Leland Stanford, to writers such as H. G. Wells and progressive activists such as Margaret Sanger, eugenics was “all the rage.”

In the first decades of the 20th century, 32 states had passed sterilization laws to address the threat of “genetic deterioration” – laws that were upheld by the highest courts. And few were as concerned about the threat of “genetic deterioration” as those in charge of the state census service.

police brutality

Born into a wealthy Boston family, Francis A. Walker served as a general during the Civil War, dabbled briefly in journalism, and eventually made a name for himself as one of the most influential economists and statisticians of the Gilded Age, ultimately becoming president of MIT. As a professional economist, Walker had a keen interest in the country’s changing demographics—and he was deeply troubled by what he saw. Like most upper-class Americans of his time, Walker believed that the original Anglo settlers had evolved to such a degree that they now constituted the superior race on the planet—even above the genuine English stock from which they originated.

To him, Anglo-Americans stood at the top of the global racial pyramid. He and his peers were, as he wrote, “so far in advance of the English, as the English are of the Teutonic race, which in turn is far above the Slavs and Celts.” He had declared of immigrants that “they are degraded men from degraded races; they represent the worst failures in the struggle for existence.” “They lack entirely the ideas and abilities appropriate to men capable of readily assuming the burden of self-care and self-government.”

He pushed not only for immigration restrictions to prevent what he viewed as Anglo-American “racial suicide,” but also supported forced sterilizations. “We must get rid of the blood of these races, not merely of the marks bequeathed by their evil and vicious past,” he wrote. “Scientific methods applied to physical diseases must be extended to mental and moral maladies, and all the power of the state must be exercised in a thorough excision and cauterization, for the good of all of us.”

Apart from his other contributions to the American way of life, Walker also served as chief of two censuses, in 1870 and 1880.

the limits of technology

The census was an instrument of racial segregation from the moment of its conception, starting with the constitutional clause that mandated counting Black people separately from white people and assigning them a value of only three-fifths of a person.

Each decade brought increasingly more “racial” categories invented and added to the mix: “free colored men and women” and “mulattos” were counted, using subcategories such as “quadroon” and “octoroon” [one-quarter Black and one-eighth Black respectively]. Categories for Chinese, “Hindoo,” and Japanese people were added, as well as designations for whites such as “foreign born” or “native.” Gradually, the census expanded to collect additional demographic data, including education levels, unemployment statistics, and medical conditions such as those affecting individuals who were “deaf, idiotic, and blind,” as well as “insane and imbecilic.” All of this, of course, was categorized by race.

Most of these questions were added to the census in a disjointed manner. They were overtly politicized and arose in response to the specific racial fears prevalent among the ruling elite at any given time. A racial category for Chinese people was added when railroad companies began bringing cheap labor from China. Various categories for “mulattos” appeared when the abolition of slavery sparked panic over the dangers of racial mixing. Questions regarding mental health and race were added following a request from a Southern senator shortly before the Civil War erupted. The results apparently showed that free Black people living in Northern states were, on average, 11 times more likely to be insane compared to enslaved Black people living in the South. Such deplorable statistics were used by Southern politicians to support racist theories and argue against the abolition of slavery.

According to Walker, these early efforts achieved very little. As an economist and statistician, he wanted to collect and process more data, and also to standardize the process and make it professional. He wanted the census to be a proper, scientific, “national repository” – not a haphazard collection of data.

But his dreams kept running up against an insurmountable obstacle: technology. The census was still being conducted and analyzed by hand. The work was slow and limited; sophisticated analyses were almost impossible. The census needed drastic improvement. What was needed was a talented inventor, someone new and ambitious who would manage to mechanize a method for automating tables and processing data. Someone like Herman Hollerith.

the inventor

Hollerith was born in Buffalo, New York, in 1860. His father, a teacher of classical studies, died when he was a child, and he was raised by his mother. In 1879, upon graduating from Columbia School of Mines with a degree in engineering, he was immediately enlisted to assist in the statistical analysis of economic data from the 1880 census, which was directed by Walker.

In his new job, Hollerith, who had gained a reputation as an inventive engineer in college, was encouraged by census officials to study the enumeration process and propose solutions to speed it up. When the 1880 census was completed, he resigned from his position to take up a teaching post at MIT, following Walker, who had by then been appointed president.

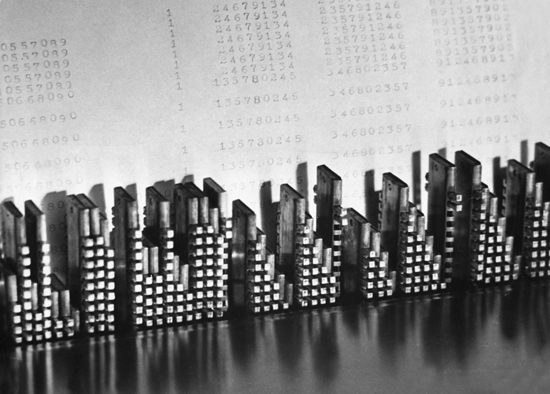

Hollerith continued experimenting with his invention and eventually settled on a plan to divide the enumeration process into stages. The first involved converting data into a format that could be read by a machine. He achieved this by punching holes in pieces of paper. The second concerned processing the data. This was accomplished by feeding the paper into a machine that read the number and position of the holes. Initially, Hollerith experimented with using a continuous strip of paper—similar to that used in the recent invention for transmitting stock prices via telegraph. However, the results were unsatisfactory.

“The problem was, for example, that if you wanted any statistics about Chinese people, you would have to run through a paper roll kilometers long just to count a few Chinese,” Hollerith later explained in a letter. The racial dimension was never out of his mind when dealing with his contraption.

Eventually, he came up with a better idea: each person would have their own punched card—a notion he conceived while traveling by train. “I was traveling west and had a ticket with what I believe is called a photographic punch… The conductor, by punching the ticket, noted the passenger’s description—whether he had light hair, dark eyes, a large nose, etc…” he explained, adding that he would do the same.

the dawn of data

In March 1890, Hollerith’s machines were installed in a building in Washington, not far from the White House. He himself oversaw the installation, running around and barking orders at workers who were carrying boxes from the street up to the third floor.

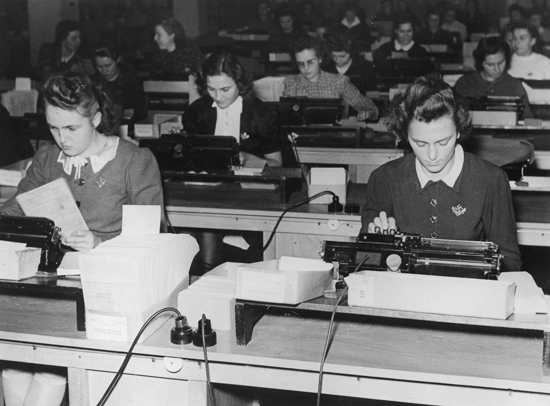

Soon, the building transformed from a drab office space into the bustling headquarters of the 11th census. Hundreds of clerks worked in shifts around the clock, collecting raw data from census takers and converting it into punched cards using special machines. The cards were then passed to another group of clerks who worked on the sorting and tabulating machines. Hollerith’s machines operated day and night, with employees crammed into the space like factory workers.

Newspapers sent reporters to observe these futuristic devices. Due to the poor efficiency of previous censuses, the press was filled with predictions of failure and incompetence. However, they were wrong.

The 1890 census—the 11th for the United States—was the most ambitious ever. It included 35 questions, ten more than the previous census, covering a broad range: literacy level, household size, occupations, the value of family property, and whether they rented or owned their home. Perhaps more significantly, it introduced a racial dimension. The census collected data on native-born Americans and those born abroad, categorizing them into multiple racial groups: whites, people of color, Chinese, Japanese, and “civilized Indians” (that is, Native Americans who no longer lived in tribal settlements). It was the first census to fully count Native Americans living within tribal territories. The census also gathered data on unemployment, fertility, citizenship, criminal history, illiteracy, and English language proficiency.

Despite the long list of questions and the need to compute a vast amount of new statistical data, the basic population count was completed in six weeks. It would take another four years to finish recording and processing all remaining data and to publish the report. This was a remarkable improvement compared to the previous census, which had taken nearly a decade.

It wasn’t only speed that Hollerith’s machines brought to the process. It was their ability to mine and sift through data, and furthermore, to combine different data sets. Such sophisticated analysis on a mass scale was absolutely unprecedented, and Hollerith’s machines had a tremendous impact on the American political elite, who were obsessed with racial issues.

Robert Porter, head of the 1890 census, who had overseen the introduction of Hollerith’s machines, was deeply impressed by their ability to classify immigrants and non-whites based on a range of demographic variables. He was particularly satisfied that it was now possible to analyze the three things that most terrified the masses obsessed with “racial suicide”: the scale of immigration, the fertility rate of immigrants, and interracial marriages (or “conjugal condition,” as it was termed in the census), all of which could now be analyzed based on age, race, literacy level, and nativity.

Simon Newton Dexter North, a former lobbyist for the textile industry who headed the 1900 census, was also astounded by the power of Hollerith’s tabulating machines. Like Walker and other census officials, he was fixated on immigration and racial mixing; he believed these phenomena corrupted and diluted the superior Anglo-American stock of the country and destabilized society.

“Immigration affects our civilization, our institutions, our customs, and our ideals,” he warned in 1914. “It has transplanted foreign languages, foreign religions, and foreign theories of government into our country; it has a decisive influence on the rapid disappearance of the Puritan way of life.”

North believed that bureaucrats and statisticians like himself were fighting a new kind of war—a war for the genetic purity of the United States. And Hollerith’s machine technology was a crucial weapon—an invention “ushering in a new era”—without which this war would surely be lost.

feeding the savage beast

At a historic moment, Hollerith’s machine technology had transformed the census from a simple population count into something resembling raw mass surveillance. For the racist political order, it was a revolutionary development. They could finally put the country’s ethnic composition under the microscope. The data seemed to confirm nationalists’ worst fears: poor, uneducated immigrants were flooding American cities, breeding like rabbits and overwhelmingly surpassing the birth rates of Anglo-Americans.

Immediately following the census, a storm of laws from state and federal governments strictly limited immigration. It began with the Immigration Act of 1891, which established the first federal immigration and border control service and turned an uninhabited island south of Manhattan into a center for rigorous immigrant screening. It continued with the enactment of many more anti-immigration laws, including one that stripped American women of their citizenship if they married an un-naturalized foreigner. And it culminated in the Immigration Act of 1924—a landmark legislation that introduced racial quotas to immigration.

This plethora of laws gave immigration service employees the power to exclude almost anyone, including “idiots, imbeciles, and the mentally defective” or those who displayed “objective psychopathic inferiority” or were “intellectually or biologically defective.” Anarchists and socialists were automatically excluded, as were those from the “Asiatic barred zone” which encompassed most of Asia, India, the Middle East, and parts of eastern Russia. Meanwhile, migration from Europe was restricted by strict quotas based on the 1890 census data – the first census conducted using Hollerith technology. Combined with the anti-Chinese laws passed in the late 19th century, these new laws constructed a virtual wall around the United States, and migration rates nearly dropped to zero.

The data provided by Hollerith’s invention did not cause the racism, nativism, and eugenics that addressed issues of class and poverty through race rather than politics and economics. But it gave racist fears concrete and solid form – and provided the data upon which these fears could be based.

For some American bureaucrats, this data-driven meritocratic system was just the beginning. North, who headed the census office from 1903 to 1909, dreamed of the day when analytical racial data could be collected and analyzed for the entire world, guiding humanity’s genetic evolution. “The necessity of eliminating the genetically inferior classes and families from the functioning of reproduction is recognized as urgent,” he wrote in 1918 from his nest at the Carnegie Foundation for World Peace, as the first global war was coming to an end. “It is every true statistician’s dream that the day will come when demographic data will be equally available across the entire planet. When this dream is realized, when comparable international statistical data truly exist everywhere, then we will possess the laws that determine human progress and we will be able to apply them effectively.” His dream would soon become reality in Europe.

Hollerith goes global

The immediate success of his invention made Hollerith rich and famous. But this was only the beginning. In 1911, he sold the Tabulating Machine Company for $2.3 million to Charles Flint, a notorious venture capitalist.

Flint acquired Hollerith’s company, merged it with several other businesses that manufactured precision mechanical tools—clocks, cash registers, coffee grinders, and scales—in order to create a monopoly in the field of computing machines, and handed over the management of this new conglomerate to a new and ambitious manager named Thomas Watson.

As Hollerith was retiring into his wealth, Watson, with ruthless tactics, used the computing technology of the aging inventor to eliminate the competition and establish a global monopoly in the early market for computing machines. The result was International Business Machines, the company we all know by the initials IBM, which was founded in 1911.

Installed in factories, business offices, and civil and military bureaucracies, Hollerith’s tabulating machines not only accelerated calculations, but also drastically reduced labor costs. Companies, state and federal agencies were buying Hollerith machines by the dozens. Insurance companies relied on them to calculate actuarial tables. Railroads used them to schedule cargo transportation and organize train schedules. In one railroad company, a single Hollerith machine operated by two people replaced the work of 20 employees. These machines ideally represented the astounding efficiency and automation of the technological revolution of the Age of Progress. And nowhere was this more evident than in the Social Security Service, the most iconic creation of the New Deal.

President Roosevelt signed the Social Security Act in August 1935, creating the first retirement program for the elderly in the United States. The Social Security Act created a tremendous need for calculations and data analysis, both for businesses and the federal government. Businesses suddenly had to keep detailed records for their employees. They had to record salaries and Social Security deductions and forward this information to federal agencies. The government, for its part, had to process all this data. It had to track contributions to individual Social Security accounts throughout each person’s lifetime. And then, when retirement time came, it had to issue monthly checks to millions of Americans.

As soon as the law was implemented, companies lined up at IBM to buy the appropriate computing machines for payroll that would meet the government’s accounting standards. A member of Woolworth’s management complained to IBM that in order to complete the paperwork required for compliance with the insurance law, the company would have to pay $250,000 per year – $4.5 million in today’s money.

IBM was the one that won the contract to oversee all accounting processes for the Social Security Service, putting companies like Remington out of competition. It was the only computer company at the time that had the experience and operational readiness to undertake a project of such magnitude. As IBM’s official history puts it, “the social security contract catapulted IBM from being a mid-sized company to the position of global leader in information technology.”

Of course, the army was a big fan of technology. In peacetime, the Department of Defense used the machines to keep track of personnel records and military pensions. But when the United States entered the war, IBM’s Hollerith technology became a vital part of the Allied military effort.

Hollerith machines were involved in almost every aspect of the war, from designing the atomic bomb to deploying troops. Special “portable” IBM machines, installed in trucks, landed with American forces in Normandy, Tunisia, Sicily, and mainland Italy. They were used equally on the home front. After the attack on Pearl Harbor, the Census Bureau pulled 1940 census punch cards from storage and reprocessed them to create lists of Japanese-Americans in every city block across six states, including California. Eventually, 130,000 Japanese-Americans were arrested and locked up in internment camps. The head of the Census Bureau at the time was thrilled with the data they managed to extract. For example, he wrote to a subordinate that if the data showed there were “801 Japanese in a community and the authorities only found 800 of them, then it is the authorities who need to conduct another search.”

together and numbers

Hollerith’s tabulating machines had tremendous success worldwide, but one particular country became obsessed with them: Nazi Germany.

Hitler had risen to power after the economic disaster that followed Germany’s defeat in the First World War. For Hitler, the problem that plagued Germany was not economic or political, but racial. (…) Hitler and the Nazis drew great inspiration from the American eugenics movement and the system of institutionalized racism that had been established after the abolition of slavery. The German solution was to isolate the “bastards” and then constantly monitor the racial purity of Germans to keep the “people” free from contamination. There was only one problem: how to distinguish a truly pure individual from one who was not?

The USA had a ready solution. IBM’s German subsidiary won its first major contract at the same time that Hitler became Chancellor. The 1933 census was carried out under Nazi pressure, as an urgent genetic screening of Germans. Among the many data collected, the census focused on gathering information regarding the fertility of German women – particularly those with a “good Aryan heritage.” The census also included a special count of religiously active Jews.

The Nazis wanted the entire census process, estimated for 65 million Germans, to be completed within four months. It was a monumental mission, and IBM’s German branch worked around the clock to complete it. The successful fulfillment of the contract was so important to IBM that its American president, Thomas Watson, personally oversaw the giant facilities in Berlin, where hundreds of female employees worked in continuous seven-hour shifts.

Watson was impressed by the work of the German managers. They had accomplished what seemed like an impossible mission – a mission made even more difficult by the special punched cards with extensive data needed to address the “political concerns” – IBM’s code for the extra data required by the Nazi regime.

As the Nazi party’s grip tightened on Germany, the regime began implementing every kind of data collection program aimed at the “purification of the German race.” And IBM helped make it happen.

«The prerequisite for every deportation was precise knowledge of how many Jews in each specific area met the racial and demographic criteria set by Berlin,» write David Martin Luebke and Sybil Milton in “Locating Victims,” a study on the use of tabulating machines by the Nazis. «Armed with this data,» they write, «the Gestapo was often able to cover, with remarkable accuracy, the total number of deportations for each racial, social, and age category.»

The massive state bureaucracy of Germany and its rearmament programs—alongside the growing network of concentration and forced labor camps—also created increased demands for data processing. Before the U.S. officially entered the war, IBM’s German subsidiary had grown to employ 10,000 people and served 300 different German state services: the Nazi party fund, the SS, the War Ministry, the Reichsbank, German Post, the Armament Ministry, the Army, the Air Force, the Navy, and the Reich Statistical Office—the list of IBM’s clients was endless.

«Indeed, the Third Reich would build incredible facilities for Hollerith machines, such as had never existed anywhere else—not even imagined by anyone,» wrote Edwin Black in “IBM and the Holocaust,” in his groundbreaking research that uncovered IBM’s forgotten business ties with Nazi Germany. «In Hitler’s Germany, the statistical and census community, steeped in Nazi doctrine, publicly boasted about the achievements that such equipment would bring to demographics.» (IBM has criticized Black’s research methods and claimed that its German subsidiary had been placed under Nazi control both before and during the war.)

The demand for Hollerith tabulating machines was so great that IBM was forced to open a new factory in Berlin to keep up with orders for new machines. At the factory’s inauguration ceremony, attended by senior IBM executives from America and the Nazi party elite, the head of IBM Germany gave a provocative speech about the important role Hollerith machines played in Hitler’s plan to purify Germany and rid it of inferior racial elements.

«We are very much like doctors, because we too dissect, cell by cell, the German cultural body,» he had said. «We record every individual characteristic… on a small paper card. Here we are not dealing with dead cards, quite the opposite; these cards come to life later, when they are sorted at a rate of 25,000 per hour based on specific characteristics. These characteristics are grouped like the organs of our cultural body and are then calculated and determined with the help of our computing machines.»

Superficially, the story of Herman Hollerith and the American census might seem like historical leftovers, the echo of an era long forgotten. But this story reveals an uncomfortable and fundamental truth about computer technology. We could thank chauvinism and the census, because they helped kickstart the information age. And as the 2020 census makes clear, the intent to precisely count our neighbors, to categorize them and turn them into statistics, continues to carry the seed of our own dehumanization.

translation / rendering Hurry Tuttle