The estimated size of the digital universe by the end of 2020, according to the World Economic Forum, will be 44 zettabytes (44 quintillion bytes); 40 times more bytes than there are stars in the visible universe. Every day, 500 million tweets are sent, 294 billion emails, 4 petabytes (4 quadrillion bytes) of data are generated on Facebook, 4 terabytes (4 trillion bytes) of data are generated by connected cars, 65 billion messages are exchanged on WhatsApp, and 5 billion searches are conducted. It is estimated that by 2025, 463 exabytes (463 quintillion bytes) of information will be generated every day.

With a quick search on the internet, the statistics, measurements and estimates we found for the “volume” of data were enough to fill several of these pages with many zeros. How many internet users are there and how fast are they increasing? What do we produce every year, every month, every day, every minute? Where is it produced? How is it produced? Zeros that are awe-inspiring, especially when compared to matter, e.g. stars. Elsewhere we found that if a byte was a gallon of water (approximately 3.7 liters), it would take 2 seconds, at the current rate of data production, to fill a medium house. What the poet means by medium house is not clarified, but in the inevitably dumbing-down sketch next to it, there was a house like the one we used to draw in kindergarten: a square with a triangle on top, probably two-story.

Data (and the generalized, universal data-ification) is the new “gold”, the new endless raw material of biocapitalism. The 4th industrial revolution is based everywhere on data: on their collection, management and processing, on their capitalist exploitation. All the miracles announced by the 4th industrial revolution, from the internet of things to the cloud, from personalized medicine to the universal mediation/machinization of everyday life, are based on data or pass through them.

[…]

No matter how strange it may seem, there is NO specific definition of what “data” is!!! One could assume that it refers to the “unit of information” – but this shifts the definitions from “data” to “information”, for which there is also NO specific and accurate definition!!It is not at all bold, on the contrary it is historically accurate, to claim that data (in the plural) is a very recent construct as a “concept”, a kind of meta-conception directly and organically related to the conception and operation of electronic computers. A specific mathematical theory that captured the operation and utility of mechanical handling of “decisions” yes or no (with the most famous creator being the American mathematician Claude Shannon) needed names (and theory) for the operation of these two-position switches (“yes” or “no”). Without exaggeration, the idea of data gave birth to electronic computers and not the reverse: anything that can be reduced to on or off (of electric current flow) is data (and under certain conditions, information).

Although the concept of information is broader, that of data relates exclusively to computers. The first use of the term in 1946 denoted “communicable and storable computer information.” In Latin, the word data is the plural of the word datum: object, but its common usage in English is in the singular denoting the uncountable, like rain or sand; as a farce of history for something that has measurement as its main purpose.

The landscape is quite blurry when we try to grasp the idea of information and data. The first references are rather to sentences that describe some object; then we think of some event as information and perhaps a little later we imagine an image, a sound or more rarely a taste or a smell. Somewhere in between, knowledge, perception and different interpretations intervene. The isolation of this information from the above interventions and generally from human perception/interpretation/understanding may bring us closer to an answer as to what information/data is. Its purpose is to be perceptible/interpretable/understandable by the machine and not by human experience; the latter comes second in order to try to perceive/interpret/understand the most mediated information.

If therefore information/data is translated human experience in the language of the machine, the collection of it in warehouses (databases and data centers) for processing is the function from which big data emerges. It is important to note this: big data is simply this enormous collection of data, although in everyday speech it also implies the processing/management of it. Experts are currently boasting about the large data warehouses they have accumulated and continue to increase, while the process of processing them still lags behind in relation to the volume they have at their disposal. Smart machine learning algorithms and artificial intelligences are being trained continuously to fulfill the wonderful promises of the experts.

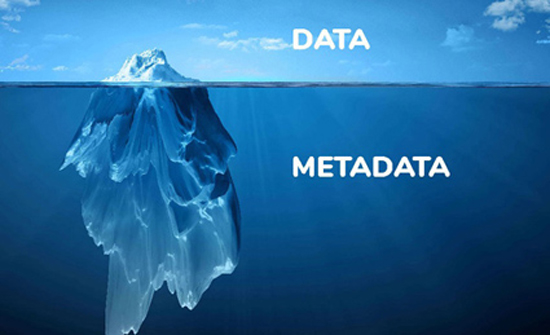

The processing of all this information that we imagine as data, such as messages exchanged, searches and visits to websites, photos and videos published, is essentially and primarily the processing of their context, and secondarily the content itself – at least as human experience would perceive/interpret/understand it. The expression of the face for example, combined with lighting, location, date, where the photo was published, whether there are other people, pixel analysis, even the way the photographer held the mobile phone are the useful information for the machine; the machine does not want to remember, it wants to analyze and store. This information/data that wants to reach the infinitely minimal scale of existence and constitutes the raw material of the new paradigm is called metadata in the language of specialists.

data for the data

The definition of metadata is: data about data; information that describes and/or summarizes other more “core” information, which could be characterized as “content”, with the purpose of facilitating their search and processing. The first description is attributed to David Griffel and Stuart McIntosh of MIT, in 1967: “Briefly, we have statements of subjective descriptions of data in an objective language, as well as distinctive codes for this data. We also have statements in a meta-language that describes the relationships of data and their transformations, which are relationships between rule and data”. Initially, metadata were the catalogs in libraries, which contained all the information about books except their content/text. Subsequently, with the first steps of digitization in the late 80s, these catalogs were transferred to hard drives and became databases, while at the same time new opportunities arose for catalogs/databases.

Separate description standards apply to the various types of data (e.g., one standard is used for a museum collection and another for digital audio or image files, for websites or medical data). Some of these descriptions may include: what medium/software was used to create the data, what their purpose is, the date and time of creation, who the creator is, where within the file system and/or network they are stored, what standards they use, what the size and quality of the data is, what the sources are and what process was used to create them.

Metadata is divided into various types such as descriptive metadata used in searching and identifying content (e.g. title, abstract, author, keywords), structural metadata indicating how complex objects are assembled (e.g. the arrangement of pages forming chapters in a book, the type of object, different versions/variants and other characteristics of digital material), administrative metadata (e.g. rights, place and time of creation), reference metadata relating to the content and quality of statistical data, statistical metadata describing the processes that collect, process and produce statistical data, and others…

The various activities in cyberspace involve and leave behind quite a few such information “traces.” Some examples:

Sending an email includes, in addition to the text itself: the sender’s name, email address, and IP address; the recipient’s name and email address; information about the email’s route through various intermediate servers; the date, time, and time zone; a unique identification code for the email and related items; the content type and its encoding; records of when the user logged in/out of their account; the email “headers”2; whether there are other recipients, in cc or bcc; whether there are attachments, their type, size, etc.; whether the email falls under a category according to any potential user categorization of their emails; the email’s subject/title; the email’s status, whether it was delivered, when it was delivered, whether it is a reply to another email, etc.; whether there is a delivery receipt.

In a phone conversation, the metadata generated includes: the phone numbers that communicate; the unique serial numbers of the two phones; the date and time of the call; the duration of the call; the location of the two phones; the numbers of the SIM cards of the mobiles, etc.

The metadata of a photograph, among other things, includes: its size in bytes; dimensions, resolution and orientation; shutter speed, focal length and flash type; date and location of creation; descriptions of what it shows; usage rights information; camera brand and model; whether it has been processed and much more3.

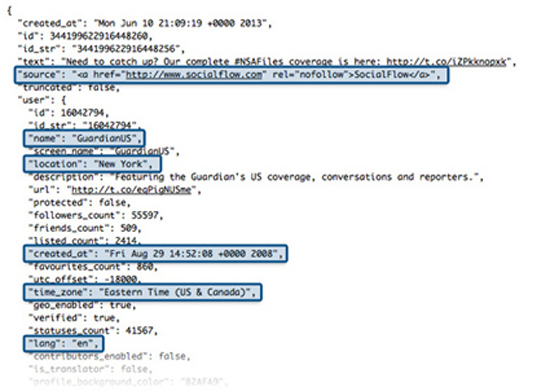

On social media platforms such as Facebook and Twitter, some of the metadata collected includes: the user’s name, username, and unique ID number; the date and location of account creation; the date and location of each post; the date and location of each login/logout session on the platform; biographical information, such as date of birth, city and country of residence, employment history, interests, native language, etc.; “friends” and “followers”; interaction with them and frequency, interaction habits; browsing habits within the platform; the type of device and application used; the number and frequency of posts, the photos and videos uploaded by users, which have their own metadata, but these platforms exploit and analyze even more (e.g., facial recognition, habits and behaviors in physical space-time), and much more. When talking about metadata on social media, we do not include the tracking of movements in cyberspace in general and outside the platform, or other data collected by these big-tech companies from various points outside of cyberspace. We are only referring to activity within the platform.

Internet browsing includes the following metadata, among others: which websites were visited; when and from where the visit occurred; the number and frequency of visits; activity within the websites, such as visit duration, cursor movement, and clicks; the IP address, internet provider, device and screen characteristics, operating system, and browser type; various data entered by the user, such as login details on platforms; searches on search engines; the results of these searches and which of them were clicked; a unique number/code that identifies each webpage to the visitor (the well-known cookies); some additional elements of the webpage stored during the visit, such as certain icons and other information related to the website’s layout (the purpose of storing these elements on the user’s computer is to enable faster access to the same page the next time).

All these and many more constitute the information that is “produced” in the digital universe and collected in databases for processing. It appears that sometimes the distinction between data and metadata is not so clear, for example in phone calls where the data is supposedly the conversation itself, but all the elements that describe it and the collection of these have greater significance for drawing conclusions regarding behaviors, relationships and related matters, than what was actually said in the dialogue. Even experts acknowledge that the distinction is somewhat blurred and essentially this ambiguity is the subject of negotiation between states/companies that want everything and privacy advocates: which of these can be considered “personal data” and which not? Which help identify the user and which not? The statement of Michael Morell, former CIA official, is characteristic: “There is no clear difference between metadata and content… essentially it is something like a continuum”.

Ignoring the technical definitions, we can initially conclude that in every case we are dealing with data—bytes of information stored on hard drives. The distinction into metadata is based on human interpretation by experts (that is, the observation/recording/analysis/timing of human experience) regarding what constitutes the content and what the context; an interpretation which, for the purposes of an ever-expanding recording, is continuously broadened, and which is intended to be processed by machines. Whereas in the first phase, library catalogs were created and used by humans for classifying and locating books, in this phase and the ones to follow, metadata is useless without machines. It is impossible for a human, or even a team of hyper-specialists, to process all this data. Without the use of “smart” algorithms, all this data is useless.

one image, a thousand data4

For years, those familiar with technology have known that photos taken from your phone contain a lot of information that you may not want to be revealed. The specific phone model you are using, the exact time and location where the photo was taken, are all stored in the photo’s metadata. This information can be displayed in almost any image viewing application and can be used to reveal the specific time and place – which, depending on your work, relationships or general desire for privacy, you may not want to share with whoever might be looking.

But metadata is not the only thing you need to consider. Tools and techniques that were once only available to intelligence agencies for collecting “open information” (also known as Open Source Intelligence or OSINT, at the national security level) are now available to amateurs. These techniques can be used to reveal personal identifying information in your photos, even if you have taken care to lock down your metadata.

Let’s look at some of the things you should consider before sharing a photo.

Who is in the photograph?

Let’s start with the main thing for which you probably use your camera: photographs of your family and friends. Face recognition technology has become so ubiquitous that it’s not hard to imagine that someone in your photo could be easily recognizable. So how easy is it for someone to identify the people in the photos you post online?

Law enforcement agencies can certainly perform this type of identification. Federal, state, and local authorities maintain databases with photographs from police cameras, driver’s licenses, passports, and arrest photos for use in crime prevention and investigations (although a recent seven-year experiment in San Diego that used facial recognition as a law enforcement tool has just ended with very little evidence that it actually helped solve any crimes).

And authorities’ access to photographs is increasing. A start-up company called Clearview AI5 claims to have acquired over three billion faces and their corresponding identities from public profiles on YouTube, Facebook, and other major platforms. Clearview’s application—which, according to some law enforcement sources, is more powerful than existing facial recognition tools they have had access to so far—has been used by over 2,200 law enforcement agencies. However, concerns regarding the use of this tool outside of law enforcement have increased, with recent revelations showing that the company allows others to trial its technology, including large retail chains, schools, casinos, and even some individual investors and clients.

However, for most ordinary users, access to facial recognition tools remains difficult. If you post a photo on Facebook, its vast custom facial recognition database can identify other Facebook users and in some cases will prompt you to tag them. Google and Apple can also recognize faces of your friends and family (whom you have tagged) in your photo library. These tags are private, and both Google and Apple say they do not attempt to match these faces with real identities.

The Russian search engine Yandex, which appears to use a different, more powerful face matching technology, is one of the few websites that allows you to find similar faces that resemble those in a photo you uploaded.

[…]Where was the photograph taken?

If you have given the camera app permission to access your location (gps), your photos’ metadata will contain the geographic latitude and longitude of the point where the photo was taken, including altitude and usually in which direction the phone was facing. But even if you have taken actions to limit your location, such as disabling these settings, location can still be determined using new tools and smart investigative techniques. This is an area of great interest to the US intelligence community, as evidenced by research efforts such as the Intelligence Advanced Research Projects Activity’s (IARPA’s) Finder Program.

Researchers and journalists at Bellingcat use these techniques, analyzing photographs from social media to improve the determination of exact locations of rocket launchers in Ukraine, terrorist executions in Libya, and bombings in Syria. By identifying buildings, trees, bridges, power poles, and antennas, Bellingcat researchers have helped develop this capability of thorough analysis of photographs and videos, publishing their techniques and offering training to journalists and researchers.

License plates, store and street signs, billboards, and even t-shirts in your photo can give indications of the language and can help narrow down the possible location. Unusual architectural features, such as churches, bridges, or monuments, can help in “reverse searching” the image. Even the reflections in your photos (and in your eyes) can contain information that can be used for geolocation. Recently in Japan, a young pop star was attacked by a man who recognized a building in the reflection of her sunglasses and revealed her residence location.

However, human detection capability has its limitations, while computers are becoming much better at automatically detecting locations. If you have uploaded images that do not have location information (gps) to Google’s photo platform, you may have noticed that location information may still continue to appear. Google uses “computer vision” algorithms to determine the likely location for your shots outside of gps, based on how similar your photos are to other known examples in Google’s data, with other images, and based on date/time stamps in your library.

When was the photograph taken?

The time and date are difficult to determine but not impossible. The “when” of a photograph can sometimes be narrowed down by looking at the weather, natural features, and light.

The weather conditions in your photograph can provide more clues about when a photograph was taken than you might think. Wolfram Alpha provides detailed historical weather data for any weather station (think of it at the zip code level) which usually includes cloud cover, temperature, precipitation, and other important atmospheric data that could help you confirm the time and date a photograph was taken.

Of course, these techniques can also be used just as easily to prove when a photograph was not taken. See the example of a photograph of a former Trump adviser, George Papadopoulos. In early 2017, Papadopoulos began cooperating with federal investigators who were investigating Russian interference in the 2016 presidential elections. His passport was seized, preventing him from traveling abroad. But on October 25, 2017—just a few days before he announced his plea—Papadopoulos posted a photograph of himself in London, with the caption #business, implying that he was in the United Kingdom. Journalists at Bellingcat, comparing some stickers on a traffic light in the background with images from Google Street View, noticed that these signs no longer appeared in recent photographs. They concluded that the photograph had been taken years earlier.

(comment: In a sense, the information that can be gathered from the above practices falls into the category of metadata, that is, peripheral/descriptive information of the content. It just goes beyond the “narrow” definition of a photograph’s metadata (as we mentioned earlier in the text), and extends to every small detail that can be utilized. Face recognition – which is a topic in itself – is based precisely on what we would call metadata; on these details, which for the sociality we know (?) are useless, but without which the translation of the face into the machine’s language, such as the distances of facial features, cannot be achieved.)

the omnipresent presence of counting

Social media platforms (as well as other platforms, companies, organizations, etc.) have access not only to information collected from activities within these platforms, but also more broadly from activities both within and outside the cyber-space. The example of Facebook tracking the activities of those who don’t even have an account on the platform is indicative:6

There are at least two basic categories of information available on Facebook for those who don’t even have an account: information from other Facebook users and information from other websites on the internet.

Information from other users

When you sign up for Facebook, it encourages you to upload your contact list so the site can “find your friends.” Facebook uses this contact information to learn about people, even if those people have not agreed to participate. It also connects people based on shared contacts, even if the shared contact has not consented to this use.

For example, I received an email message from Facebook, which lists the people who have invited me to join Facebook: my aunt, an old colleague, a friend from elementary school, etc. This email message includes names and email addresses – including my own name – and at least one web bug7 designed to notify Facebook’s web servers when I open the email. Facebook records this group of people as my contacts, even though I have never agreed to this type of data collection.

Similarly, I am certain that I am in some photos that someone has uploaded to facebook – and I have probably been tagged in some of them. I never agreed to it, but facebook can and does it.

So, even if you decide that you should sign up for Facebook, remember that you may be giving the company information about someone else who did not agree to participate in the tracking platform.

Information from other sites on the internet

Almost every website you visit that has a “like” button informs Facebook about your browsing habits. Even if you don’t click the “like” button, your web browser (such as Firefox) sends a request to Facebook’s servers to display the button on the webpage. This request includes information indicating the name of the page you are visiting and any Facebook-specific cookies that your browser may have collected. (See Facebook’s description of this process8) This is called a “third-party request.”

This allows Facebook to create a detailed image of your browsing history – even if you have never visited Facebook directly, let alone opened an account there.

Think about most of the websites you’ve visited – how many of them don’t have a “like” button? If you manage a website and include a “like” button on every page, you’re helping Facebook create profiles of your visitors, even those who avoid the platform. Facebook’s “share” buttons on other websites – along with other tools – work slightly differently from the “like” button, but they effectively do the same thing.

The profiles that Facebook creates for non-users do not necessarily include so-called “personally identifiable information” (PII), such as names or email addresses. But they do include quite a few unique patterns. Using Chromium’s NetLog9, I conducted a simple five-minute browsing test last week that included visits to various websites—but not Facebook. In this test, the data without PII sent to Facebook included information about which news articles I read, my dietary preferences, and my hobbies.

Given the precision of this kind of mapping and targeting, my personally identifiable information (PII) is not necessary for identifying me. How many vegans are examining computer part specifications from ACLU offices, reading about Cambridge Analytica? In any case, if Facebook were to combine this information with the “web bug” from the aforementioned email message—which is clearly linked to my name and email address—not much imagination would be needed.

I would be amazed if Facebook did not connect these dots, given the goals it claims for data collection: “We use the information we have to improve advertising and measurement systems, so that we can display relevant ads within and outside our services and to measure the effectiveness and reach of ads and services.”

This is, in essence, exactly what Cambridge Analytica did.

[…]There is also a third category of information that Facebook collects, beyond the platform itself: those that can be detected in physical space. Through a service called “offline conversions,” the impact that Facebook ads have in the real world can be measured. By recording purchases in stores, phone orders, bookings, and more, businesses can create a list of these transactions along with customer details (name, phone, email, etc.), which they will “upload” to Facebook, so that it can be matched with those individuals who are in its user database. This way, they can know, for example, whether a purchase was made after a specific search or if they had clicked on the ad. Perhaps now it makes some sense why they ask for email and phone when we make a purchase…

the derivatives

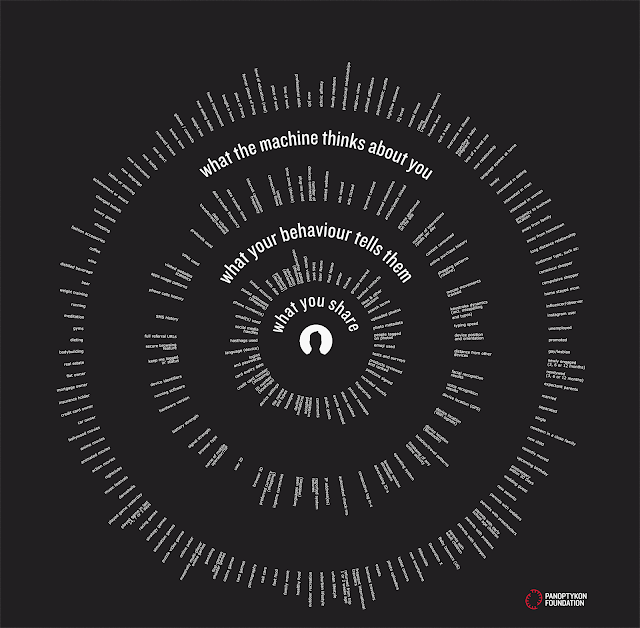

The primary goal of collecting and processing these massive volumes of metadata is the analysis and shaping of behaviors10 either for commercial purposes or for broader surveillance (two, not entirely distinct, fields). The recording of all our internet-mediated actions, and the peripheral information of these actions – that is, the recording of the content and the description thereof, where the more the algorithm’s penetration capability increases, the higher the level of detail becomes – shapes what is called a digital profile. A four-dimensional digital identity, as behaviors are evaluated within (cyber)space and (cyber)time.

Schematically, we can describe digital identity as consisting of three levels. The first includes activities mediated directly (either directly or indirectly) through the internet, such as browsing and searching the internet, texts and photographs we “upload”, the applications we use, electronic payments, etc. The second level encompasses behavioral observations; the information/metadata describing our direct activities, in ways that escape our immediate observation/action. The time we spend online, the categories of content we visit, the manner and speed with which we use buttons/keys, movements on touchscreens, etc.; and the correlations between them. And at the third level is the machine’s interpretation. The analysis of data by “smart” algorithms, and the extraction of statistical conclusions, not only about what we do, but about who we are; the (mechanical) analysis of behavior.

We translate from a study by the “Privacy Commissioner of Canada” (an official body of the Canadian government, established in 1977):11

Indeed, metadata can sometimes be more revealing than the content itself. In the digital age, almost every online activity leaves some kind of personal trace. Computer scientist Daniel Weitzner considers metadata “undoubtedly more revealing [than content], because in reality it is much easier to analyze patterns in a large universe of metadata and correlate them with real-world events, than to perform a semantic analysis of all someone’s emails and all their phone calls.” Even the terms entered into search engines can be used to identify individuals and reveal sensitive information about them. John Battelle coined the term “database of intentions,” which he describes as “the complete record of every search ever entered, every result list ever submitted, and every path ever taken as a result.” Battelle states that “The information represents, in aggregate form, a placeholder for humanity’s intentions—a massive database of desires, needs, and sympathies that can be discovered, called up, archived, tracked, and exploited in any number of ways. Never in the history of civilization has such a beast existed, but it is almost guaranteed to develop exponentially from here on out.”

And from a report by the American Civil Liberties Union of California (ACLU of California):12

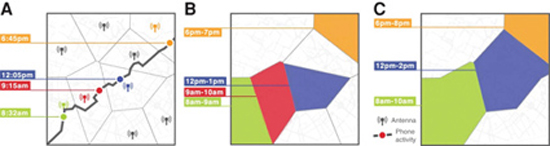

In fact, metadata mining can not only expose sensitive information about the past, but also allow an observer to predict future actions. For example, studies have shown that a person’s future location and activities can be predicted by searching for patterns in their friends and collaborators’ location history. A security expert also warned that detecting phone calls from key executives of a company to or from a competitor, an agent, or a brokerage firm can reveal the likelihood of a corporate acquisition before any public announcement is made.

Upon a second look, our perception of (big) data as a large volume of information expands to include the factor of time. “Databases of intentions” are not static; they draw lines and detect interactions over time. Through this process—and with this logic, the logic of the algorithm—they analyze and comprehend the past, attempting to predict or/and shape the future. Could we argue that the mediation of the machine changes the very language through which we interpret the past, the present, and imagine the future? A question that certainly does not fit within the present text, but arises spontaneously when the machine of predictive intentions unfolds before us.

the identification of the anonymous

As a “side effect” of this metadata collection and the creation of digital identity, the nightmare of privacy advocates emerges: the identification of the anonymous. An MIT study in 2018 showed how someone can be identified using large sets of anonymous metadata. We translate from the relevant publication:13

A new study from MIT researchers finds that the growing practice of collecting massive, anonymous datasets about people’s movement patterns is a double-edged sword: while it can provide deep insights into human behavior research, it could also put people’s private data at risk.

Companies, researchers and other entities have begun to collect, store and process anonymously data containing “location fingerprints” (geographic coordinates and time stamps) of users. The data can be obtained from mobile phone records, credit card transactions, smart public transport cards, twitter accounts and mobile applications. The merging of these data sets could provide rich information on how people travel, for example, for optimizing transportation and urban planning, among others.

But with big data, major privacy issues arise: Location traces are highly individual-specific and can be used for malicious purposes. Recent research has shown that, considering only a few randomly selected points in mobility datasets, one could identify and learn sensitive information about individuals. With merged mobility datasets, this becomes even easier: Someone could potentially match an anonymous dataset with user trajectories, identified data from another source, to identify the anonymous data.

In their study, the researchers combined two sets of anonymous “low-density” data – few records per day – regarding mobile phone usage and personal movements with mmM in Singapore, which were recorded for over a week in 2011. The mobile phone data came from a large mobile network operator and included time stamps and geographic coordinates in over 485 million records for over 2 million users. The movement data contained over 70 million files with time stamps for individuals moving around the city.

The researchers’ model selects a user from one dataset and finds a user from the other dataset with a large number of matching location points. Simply put, as the number of matching points increases, the probability of incorrect matching decreases. After matching a certain number of points in a trajectory, the model excludes the possibility of false matching.

Focusing on typical users, they calculated a matching success rate of 17% over one week of concentrated data and approximately 55% for four weeks. This estimate rises to about 95% with data collected over an 11-week period.

What does this mean? It means that identification can be done through the combination of metadata, which may be (and) anonymous! Here the “privacy battle” muddies the waters. On one hand, there is the “well-intentioned” analysis of behaviors to improve cities and the like, and on the other hand, the problem of exposing personal data. In relevant legal texts we found, the definition of personal data referred to information directly linked to an identified individual. Thus, according to this definition, metadata does not fall under personal data, and the great debate begins regarding redefining the definition and setting boundaries for data collection and identification by companies and states. We won’t delve into these deep waters now.

brief epilogue

Maintaining a distance, the issues arising from the collection/processing of (meta)data are twofold: first, the recording/analysis of behaviors by states/companies, with the purpose of shaping them, and second, the recognition/identification by the state/services, with the purpose of surveillance/suppression and law enforcement.

The issue of privacy/anonymity, although (perhaps) useful up to a point as a “cyber-dam,” is misleading when approaching a comprehensive political response. The struggle for privacy does not mean we want to be anonymous when we pay our water bill, insurance premiums, or fines. There, it accepts that identification must exist; how else could it be done? (Of course, even so, it would still be misleading). The struggle for privacy has to do (also) with the collection of metadata in bulk, where anonymity should prevail; but apparently, even this work gets done – no problem!

If authority needs identification in order to enforce the law – it seems that it now has new “indirect” ways of identification at its disposal – the science of behavioral analysis is not interested in how we are called, but in who we are. The machine that uses thousands of volunteers for the vaccine, indifferent to their names, focuses on their individual reaction, in order to produce regularities that it will impose on identities. There, the “right to privacy” is simply redundant.

Wintermute

- What are data and who do they belong to? – Cyborg #13, October 2018 ↩︎

- A piece of code that exists in every email and contains a summary of such meta-information. ↩︎

- You can see a (rather) exhaustive list of metadata that a photograph can have here ↩︎

- Translation of parts of the article “What are my photos revealing about me”, from the mainstream site “The Next Web“. The article has several references to other articles that are useful for what it mentions, but we will not reproduce them here for space economy. ↩︎

- See also related reference to “Recognition of the desolate“, in the relentless machine, 22/1/2020” ↩︎

- Translation of parts of the text: Facebook is tracking me, even though I’m not on Facebook ↩︎

- A technique used in websites and emails to check if the user “opened” and saw the content. It is usually called a web beacon. ↩︎

- What information does Facebook get when I visit a site with the Like button? ↩︎

- A chrome tool that allows someone to view technical information about what happens in the background when browsing the internet. ↩︎

- See also the “big data: surveillance and shaping behaviors in the 4th industrial revolution” – Cyborg #16 10/2019 ↩︎

- Metadata and Privacy: A technical and Legal Overview – October 2014 ↩︎

- Metadata: Piecing together a privacy solution – February 2014 ↩︎

- The privacy risks of compiling mobility data ↩︎