In recent years, increasingly advanced technology has emerged for monitoring and supervising employees in the workplace and during working hours – and even more so, outside of these two.

Employers monitor employees’ computer usage by tracking keystrokes; monitoring the websites they visited, what they “downloaded” and viewed; even looking at their personal blogs and their activity on social media platforms, such as MySpace, Facebook and LinkedIn.

One of the most controversial issues in privacy legislation in the United States is whether an employer can monitor emails that are sent or received through their servers or even from personal accounts, such as Gmail or AOL.

Apart from technologies that help employers monitor employees’ computer or internet activities, there are two types of technologies that correspond to an employee’s physical presence and movements. The first, biometric technology, identifies (or verifies the identity of) an employee by scanning a part of the body and recording and storing a digital representation of their biological characteristics. Location tracking technologies – GPS, mobile phone signals, radio frequency identification devices – monitor an employee’s movements around and outside the office, from signals emitted by something they carry, wear or use.

Concerns about the ever-increasing use of high-tech surveillance devices in American workplaces – what one researcher called “Geoslavery” – continue to grow. The use of these technologies has sparked criticism regarding its impact on employee morale, violations of privacy, breaches of Fourth Amendment protections, and the erosion of union rights.

However, until today there has been insufficient examination of the way in which biometric technologies (and to a lesser extent, location-aware technologies) could reveal information regarding medical care, medical conditions, potential medical conditions, and undiagnosed disabilities. Apart from the scientific literature and the U.S. military security complex, most studies on the medical implications of biometrics have been conducted outside the United States – which is not surprising, as other parts of the world are far ahead of the U.S. on issues of technological privacy in general. The European Union as well as non-EU countries have examined not only the issue of personal information revealed by biometric identifiers, but have also adopted strict standards for the transmission and protection of data collected through biometric or other monitoring technologies.

With the current situation in this country, workers who are forced to undergo such monitoring remain vulnerable to consequences such as discrimination based on these characteristics or classifications, or exclusion from insurance coverage due to potential treatment expenses. The situation could become even worse with the accelerating introduction of biometric systems and geolocation systems into the workplace, and as technology becomes increasingly sophisticated.

Biometric technology

The term “biometrics” refers to computer-based technology that measures unique biological or physical characteristics for the purpose of identification. The unique biological or physical characteristics that are measured are known as “biometric identifiers.” These include:

- Hand geometry – Measurement and recording of hand length, width, thickness and surface area.

- Facial recognition – Characteristics such as the distance between the eyes, the length of the nose, and the angle of the jaw. Of all biometric technologies, facial recognition is the least technologically advanced and is considered the most concerning due to its ability to remotely capture biometric identifiers; at some point, the technology will be advanced enough to analyze images captured by hidden security cameras.

- Fingerprints – the digitized images, as opposed to “ink” fingerprints, which are scanned and stored.

- Voice recognition (also known as “speaker identification”, it is different from “speech recognition”, which recognizes words and their syntax and is not a biometric identifier) Voice recognition technology identifies people based on differences in voice, which arise from physiological differences (the physical structure of an individual’s vocal system) and the individual’s behavioral characteristics (speech habits).

- Scanning the retina – Retinal biometric recognition is based on comparing the complex pattern of blood vessels located at the back of the eye. Infrared light illuminates the retinal vascular network, and this image is reflected back to the sensor as a wavelength. An algorithm then creates a unique template based on the pattern of the retinal blood vessels.

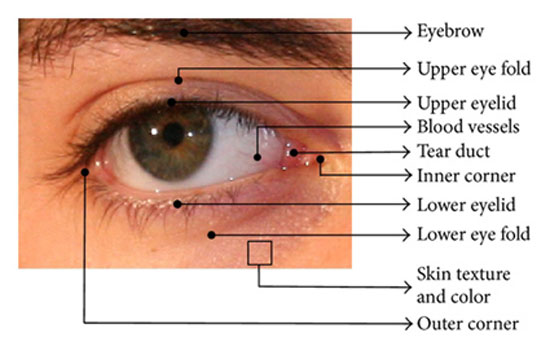

- Iris scanning – an infrared camera illuminates the visible, colored part of the eye and creates an image that is converted into a digital pattern.

- Scanning of veins – the pattern and structure of blood vessels that are visible on the back of a person’s hand or fingers are scanned, the algorithm records the characteristics of the vascular pattern (blood vessel branching points, vessel thickness and branching angles) and stores them as a template for comparison with subsequent samples from the registered individual.

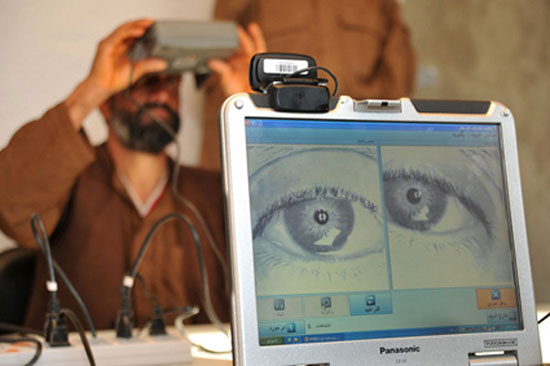

To register in the system, an employee must submit a template with their biometric identifier. Despite frequent assurances from employers, the creation of a biometric template is not a completely benign process. Creating an iris template, for example, requires infrared radiation and capturing the image with a camera at a distance of 8-13 inches from the employee’s eye. It has been reported that scanning the retina could cause thermal injury to the back of the eye. The created template is stored in a system and then read by data collection devices (Data Collection Devices – DCDs) such as sensors or scanners. The next time the individual “connects” to the DCD, their body part is input and verified against the stored template.

The use of surveillance technology in the workplace

Although some DCDs feature security characteristics, such as access control to doors or “smart card” reading devices, biometric technology is more commonly used in workplaces for time tracking rather than for security. The biometric equipment available commercially for employers to stop “time theft” and “buddy punching” [stm: The act of clocking in/out for a colleague] is a multi-million dollar business.

For example, Union Pacific Railroad replaced timekeeping based on crew members’ self-reporting on a list with iris recognition biometric technology. The device is not used for the security of railway facilities – only for “presence/absence” tracking. Other employers use retinal scans for the same purpose.

The city of New York installed hand geometry biometric scanners that were something more than high-tech “time clocks,” as part of an electronic timekeeping and payroll system for public services, which so far has cost approximately 700 million dollars. Instead of signing in on some time list, employees were required to insert their hand into the biometric equipment. The hospital installed a hand geometry scanner in 1997 for physical access control and to monitor employee attendance.

Other biometric devices available in the market for employers to monitor employee “productivity” include computer mice with fingerprint readers and keyboards that read hand veins from a sensor.

More and more employers are using geolocation technology along with or instead of biometrics to track employees. Global positioning systems (GPS) are often found in the workplace as navigation devices in employer-owned vehicles or corporate mobile phones or other portable communication devices where GPS tracking capability is enabled. Radio frequency identification (RFID) devices have become widespread in healthcare facilities. RFID devices contain microscopic circuits, in some cases as small as a grain of sand, that hold unique identification data and, through a small antenna they have, can be read from a distance by an RFID reader.

Although a detailed discussion of other technologies is outside the scope of biometrics, we note that geolocation also raises privacy concerns. Like biometric data, geolocation technology can reveal personal information to an employer that they otherwise would not be able to know.

Some information is relatively harmless. A company with RFID readers installed at access points could know, for example, whether an employee eats in the corporate cafeteria or at some restaurant outside the building.

However, if an employee has a company mobile phone or other portable device that has an RFID circuit, or is inside a company car with GPS, which the employee uses for personal use as well, recording is made of where this employee goes and when (even during breaks or after work). In some cases, an employer who monitors employee movements may learn confidential medical information simply by looking at specific destinations.

For example, an employer might suspect that an employee has an alcohol problem because they stop for lunch at a local church that hosts an “alcohol dependency” meeting, or that an employee has a serious illness, from their visits after work to an AIDS clinic. Likewise, most people do not know that the GPS systems installed in New York taxis do not have navigation capability, but simply track the vehicle’s movements (and, by extension, the driver’s movements). A midday stop at a specific location could reveal that the driver stopped at a mosque to pray rather than at a dinner for food – or that they were visiting a doctor at a hospital specializing in cancer treatment.

The body’s information

Scanning biometric identifiers such as the iris, retinas, or hand veins can reveal information regarding existing medical conditions, as well as medical predispositions, based on these specific biometric patterns. The “vein” of data that can be extracted from biometric data is so rich that a study characterized the current situation as “the informationalization of the body.”

The direct medical implications of using biometric technology are considered those arising from potential risks to human health from using this technology. Indirect medical implications involve the detection of sensitive medical information regarding an individual’s health status from biometric data. Information of this nature may fall into the hands of employers or insurers as a result of what is called “function creep.” “Function creep” is defined as “the process by which the original purpose for obtaining information is expanded to include other purposes, beyond what was initially stated” or “the expansion of a process or system, where data collected for a specific purpose is subsequently used for another unintended or unauthorized purpose.”

Employers who collect biometric data for time tracking, access and/or security purposes may, as a result of “function creep”, extend the use of this data for an intentional, but unauthorized purpose – to discover information regarding employees’ medical conditions, existing or potential medical conditions, and/or the need for accurate medical care. Although no such cases of abuse have been reported, the risk is not entirely hypothetical; it is now known that certain medical disorders or predispositions to some medical conditions are associated with specific biometric patterns.

Which biometric identifiers are known (or there are indications) to show which medical conditions or predispositions?

- The measurement of hand geometry is a potential source of detecting disorders, indicated by specific patterns, such as gout and arthritis. Geometry can also be an indicator of Marfan syndrome, an inherited connective tissue disorder that can affect the heart, blood vessels, eyes, and skeletal system. Individuals with Marfan syndrome are typically tall and thin, with disproportionately long arms, legs, fingers, and toes (some specialists believe that Abraham Lincoln may have had Marfan syndrome).

- Researchers in the field of dermatoglyphics, the study of skin ridge patterns on parts of the hands and feet, have identified characteristic patterns of fingerprints that are known to be associated with certain chromosomal disorders, Down syndrome, Turner syndrome and Klinefelter syndrome. Researchers at Johns Hopkins reported that they found a relationship between an unusual fingerprint pattern, known as a digital arch, and a medical condition called chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction (CIP).

- The eyes can reveal a variety of health conditions, such as AIDS, Lyme disease, congestive heart failure, and cholesterol levels; even diseases such as leukemia, lymphoma, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and sickle cell anemia can affect the eyes. The pupil responses of the eye can vary if the person has consumed alcohol or taken drugs or is pregnant.

- Scanning the retina measures the patterns of blood vessels at the back of the eye, which are subject to the effects of aging and can change with certain medical conditions; retinal microvascular signs appear to be associated with long-term risks for type 2 diabetes and hypertension, as well as vascular diseases such as stroke and heart failure.

- While enrollment and recognition with iris scanning biometric systems are generally not affected by an acute eye condition, patients with iritis could pose a problem for iris recognition, especially if pharmacological dilation is required. Cataract surgery can alter the texture of the iris in such a way that iris pattern recognition is no longer feasible or the likelihood of false rejections increases.

- It is widely recognized that voice recognition technology can reveal anger, nervousness, or distress. The information commissioner of the Republic of Slovenia acknowledged the possibility that a company using voice recognition for access control could subsequently use the collected biometric data to determine the emotional state of individual employees.

- Scientists are already thinking that facial features can be used to detect a person’s emotional state from expressions. Facial recognition biometrics, such as hand geometry, can reveal Marfan syndrome, because patients with Marfan have a specific symmetry parameter in their facial geometry.

Medical information can also arise from the process itself, that is, from problems in registration or recognition failure. First, injuries or illnesses may prevent an individual from being registered and recognized by the system, e.g., eye conditions could prevent iris scanning, arthritis interferes with hand geometry measurement, and finger burns can prevent fingerprint acquisition. Second, medical information can be derived by comparing selected biometric characteristics recorded during initial registration and subsequent identifications. For example, facial geometry measured at different time periods can reveal certain endocrine disorders. Additionally, infrared cameras used to create a biometric template can detect surgical modifications to the body, because the temperature distribution in reconstructed and artificial tissues is different from that in natural ones, and thus they can easily and covertly detect dental reconstruction, plastic surgery, added or removed skin tissue, implants, scar removal, skin repair via laser, and tattoo removal.

The impacts on the employee

The consequences for an employee whose existing medical condition or predisposition to develop such a condition is revealed through biometric scanning to their employer are obvious. Such information could potentially affect access to insurance coverage or place the employee in illegal discrimination due to disability or perceived disability. A study on the use of biometrics reached the same conclusion:

Moreover, by linking the biometric database with other databases (e.g., credit card transactions), we know where the individual was and at what time. Besides personal privacy, there are also concerns that biometric data can be exploited to reveal a user’s medical condition. Such information could lead to potential discrimination [against] certain users in employment or/and the provision of benefits (e.g., health insurance).

Any discrimination by the employer based on the employee’s medical condition or perceived medical condition would be difficult to uncover, let alone prove, for various reasons. Firstly, because the information is obtained covertly, the employee does not know that the employer has gained knowledge of their health issues or physical condition. Secondly, the employer may know even more about the medical history than the employee themselves, if the information derived from biometric identifiers relates to a genetic predisposition to develop a disease that the employee has not been tested for.

An employee with a condition that does not require reasonable accommodation has the choice to disclose it or not, but this choice is removed when confidential medical information is disclosed as a result of an unauthorized and unforeseen function (function creep). Unlike an employee who voluntarily discloses information, the one whose biometric data was recorded and misused does not have the opportunity to challenge any perceptions based exclusively on information derived from biometric identifiers. Where the employer may have (a) incorrectly perceived that there is a disability, because the data have been misinterpreted; (b) incorrectly perceived that the employee is currently “ill,” whereas the biometric data only indicate the likelihood of developing a condition in the future; (c) incorrectly assessed the severity of the recognized medical condition, and consequently erroneously concluded that it affects the employee’s ability to perform the essential duties of their position.

Similar concerns arise with access to health insurance. As the National Workrights Institute once warned, “with the cost of employer-provided medical insurance continuing to rise, employers have a strong economic incentive to access and use medical information derived from biometric data.” An employer might believe that their financial interests would be affected by hiring an individual who has serious medical conditions or may develop such conditions in the future, who is likely to require expensive medical care, which would be paid by the employer directly (if insured) or indirectly (if premiums correspond to years of experience). Despite the legal requirements of the ADA or the FMLA, the employer will also anticipate lost productivity from absences when the employee is too ill to work or needs leave for medical appointments.

In its 2009 report, the Irish Council for Bioethics noted a “particular concern” regarding the possibility of “obtaining additional personal health information through biometric identifiers” and the “extensive impacts” these could have on the individuals involved.

Protection and regulation of biometric data usage

The privacy issues arising from authorized and unauthorized uses of biometric identifiers have been the subject of several studies conducted by research institutes to assist in formulating government policies. In some of these studies, and in articles written by European researchers, the issue of inappropriate use of medical information derived from biometric systems has been specifically examined.

Also impressive in studies outside the United States is the examination of the ethical issues inherent in the collection and use of biometric data. The “fair information principles” include the principle of proportionality: that the use of biometric data “can be justified within the framework of application and also that no other identification means, without biometric data, can meet the requirements.” There would possibly be less concern about misuse of medical data if the principle of proportionality were taken into account:

“For example, when biometric data is processed for access control purposes, the use of such data to assess the emotional state of the data subject or to monitor in the workplace, would not be compatible with the original purpose of collection.”

A related principle is the “purpose limitation principle”. Article 6 of Directive 95/46/EC defines that:

“Personal data must be collected for specified, explicit and legitimate purposes and must not be further processed in a manner incompatible with those purposes. Moreover, personal data must be adequate, relevant and not excessive in relation to the purposes for which they are collected and further processed.”

As noted, the European Union has approved regulations regarding the processing of personal data. Outside the EU, measures to control the unjustified use of biometric data and to protect the data created have also been published. The Australian Privacy Commission, for example, approved a Code of Practice for the Protection of Personal Biometric Data that specifically protects employee data containing biometric information.

The Information Commissioner of the Republic of Slovenia issued the “guidelines regarding the introduction of biometric measures”, a lengthy and detailed protocol that contains significant protection for both public employees and the private sector. The use of biometrics in the public sector is regulated by statute and biometric measures can only be used if they are necessary for security or the protection of confidential data and this purpose “cannot be achieved by milder means”. Employers in the private sector are subject to even greater restrictions on implementation and must inform employees in writing before using the biometric system.

In the United States, legislative protection and regulation of biometric data at the state or local level is limited, and previous attempts to expand it have been largely unsuccessful.

The «Texas Business and Commercial Code» prohibits the unauthorized commercial use or disclosure of «biometric identifiers»; any individual who «possesses» a biometric identifier must «store, transmit, and protect it at least in a similar manner as other confidential/private information». In the state of Washington, the motor vehicle law contains privacy protections regarding biometric data for driver’s licenses. Illinois requires private entities that possess biometric data to develop a written policy establishing a retention schedule and instructions for the permanent destruction of information; to protect biometric data; and to obtain written consent before collecting an individual’s biometric identifier. The statute also prohibits the commercial use of biometric information. Colorado includes «biometric data» in the definition of «personal identification information», for which private businesses must have a record destruction policy.

A bill introduced in Georgia’s legislature, the “Biometric Information Protection Act,” would prohibit employers, both in the private and public sectors, from using for identification purposes or as a condition of employment, any information derived from biometric data or “location tracking technologies.” A bill in New Jersey would limit the commercial use or disclosure of biometric identifiers; would require secure storage of the data; and would require a state entity that possesses an individual’s biometric data to establish a “reasonable process” that would not “unduly burden” the user to correct inaccurate information.

The informatization of the body: What biometric technology could reveal to employers about current and potential conditions

American Bar Association, National Conference on Equal Employment Opportunity Law (New Orleans, April 7, 2011). (The A.B.A. is a voluntary bar association established in 1878, without specific jurisdiction in the U.S.)

translation by W.