Sometimes on the internet we are asked to prove that we are not robots. This usually happens when creating accounts on various platforms or when identifying ourselves upon entering them. In this way, these platforms try to deal with potential “malicious” programs that have been created in order to automatically generate many accounts or to repeatedly test various passwords in order to gain access to third-party accounts.

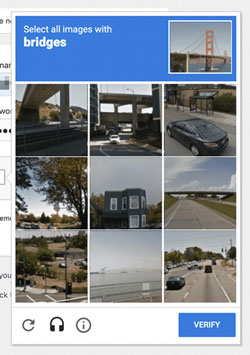

This function is called CAPTCHA (Completely Automated Public Turing test to tell Computers and Humans Apart) and is often referred to as the reverse Turing test.1 It appears as an image with distorted letters and numbers, where we need to recognize and type them, or as a photograph where we need to check the points where an object described in a sentence appears (e.g., select the points in the photograph with the crosswalks).

The reason this works is because the “malicious” program’s algorithm does not have the ability to recognize the shape of letters in the first case or to understand what object is being sought in the second case and then recognize its shape within the photograph. Certainly not with the accuracy that a human can and probably not for much longer. Thus, the human-user is called upon to confirm that they are human (and only that, not that they are the specific person) by demonstrating a capability that the machine does not have. That of interpretation.

Although the field called upon to bridge this gap for the benefit of the machine is primarily that of visual recognition, there is also a need for the machine’s “understanding” of what is requested as an object. That is, the interpretation of the word or sentence into a certain form, and subsequently the recognition of that form within the image. Thus, the goal is not simply to identify the sample image with one of those that the machine may have stored in a database, in order to find the corresponding one through comparison; but rather the very process of conveying and perceiving the meaning that words and things possess.

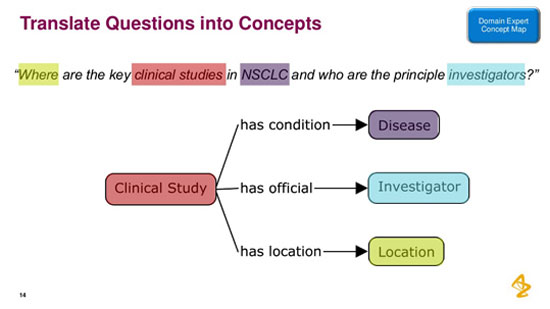

The difference from how one might imagine that a machine extracts conclusions, by gathering data and metadata which it stores, categorizes, and uses to create statistics and diagrams (a static process if we think about it, where each subsequent step is simply the increase of data and the redesign of statistics), is that in the case of semantic technology, the goal is to define the relationships between them, upon which the machine will base itself in order to proceed to new conclusions that do not directly arise from this data and the declared relationships; to construct new relationships that have not been defined for it and thus to acquire the ability of interpretation.

One thing we must keep in mind when trying to approach the issue of “smart” machines is that we are talking about a set of technologies that compose the field of artificial intelligence; that is, it is a “collaboration” of many fields that are necessary, such as: neural networks, machine learning algorithms, robotics, image recognition, natural language processing, etc. Thus, the field of semantics is also a piece in the mosaic of the search for a – as much as possible – “human” machine.

What semantics technology covers in this search is knowledge representation and reasoning creation. We translate from the relevant lemma in wikipedia:2

Knowledge representation and reasoning is the field of artificial intelligence devoted to representing information about the world in a form that a computer system can use to solve complex tasks such as diagnosing a medical condition or engaging in natural language dialogue. Knowledge representation incorporates findings from psychology about how people solve problems and represent knowledge in order to design formalisms that make complex systems easier to design and build. Knowledge representation and reasoning also incorporate findings from logic to automate various kinds of reasoning, such as applying rules or set and subset relationships. Examples of knowledge representation formalisms include semantic networks, systems architecture, frames, rules, and ontologies.

One step closer to interoperability: Semantic metadata3

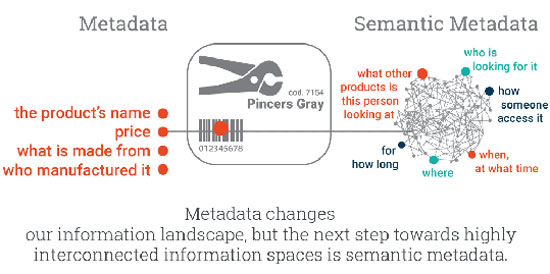

Metadata radically changes the way we think about and use information to create and transfer knowledge. Semantic metadata even more so.

They allow us to add so much detail to an existing object, to connect it to an endless number of other objects, and to facilitate searching, accessing, and using it. And even though we still have a long way to go from what Ted Nelson4 calls Interoperability, properly setting metadata – that is, setting them correctly with semantic technologies – brings us one step closer to our effort to fully and richly express “the complexity of interactions in human knowledge.”

With their “silent presence” underlying every digital activity, metadata plays a transformative role in the ways we interact with information.

As professor Jeffrey Pomeranz, author of the book Metadata, notes: “Metadata, like the electrical grid and the highway system, recedes into the background of daily life, taken for granted as part of what makes modern life run smoothly.”

If you follow recommended videos on YouTube or use your phone to find nearby restaurants or conduct a search on Amazon, you are already reaping the benefits of “data about data” (as metadata is often defined). Other examples of metadata range from the size and format of our digital books and documents, to the creation dates of our files, to sensor data from our smart devices and the last song we searched for on iTunes.

As fundamental as metadata may be in changing the information landscape, it is only the beginning. The next step toward an interconnected information space is semantic metadata. What differentiates semantic metadata from metadata is the level of interconnection. Semantic metadata is deeply interconnected and rich in context. Think of a price tag in a store. Conceptually, this tag is a very basic example of metadata.

It contains information intended for the customer, such as the product name, its price, who made it, etc. However, the label also contains a linear code (barcode) and many other codes that are usually machine-readable and used to automate the purchasing process in the store.

But does this last metadata, this in the barcode, have any meaning for us? Can we understand the symbols and signs in it and correlate them with other connected events?

No, we cannot. Without giving additional meaning to the codes, the information elements will have limited value, because we will not be able to correlate them with anything else. Thus, in order to interpret them, we must use semantic metadata.

Admittedly, the differentiation between metadata and semantic metadata is difficult. But where semantic metadata is highlighted is through semantic technologies, with the help of which this data (or metadata) is structured to express meaning.

Imagine that the data of this same label is linked to a wide range of additional interconnected information: the manufacturer’s website, who they are, what other products they offer, which category the product belongs to, similar products, etc. Now imagine another group of metadata containing context-based information such as: who is viewing it, what time, where, for how long, what other products this person was looking at, and so on.

What emerges is an extremely adaptable, highly personalized dynamic information system that has the ability to change, depending on who, when, where and how someone accesses it. And no matter how much it may sound like sci-fi, it’s not. It’s exactly what semantic meta-data constructs.

With semantic meta-data, the details of the tag will be linked to their machine-readable definitions, among themselves and with external sources. Thus, the meta-data from the tag, along with all its elements, will acquire valuable meaning and the tag will be transformed into a highly interconnected object.

By connecting hundreds of millions of entities, large media companies, businesses and non-profit organizations are already creating magical and visionary experiences from semantic meta-data. As Yosi Glic also points out in his article “Understanding the Real Value of Semantic Discovery”, when he writes about Netflix and their annual investments of 150 million dollars in semantic technologies:

“Only semantic technology can know if a user prefers for entertainment a ‘hard army of one person’, a ‘race against time’, ‘criminal heroes’ or ‘a romantic movie’.”

It is true. With semantic metadata, the opportunities for interconnection are endless. By enriching the identity, discovery, and utility of digital resources, semantic metadata allow the user to know more.

Understanding semantic metadata and leveraging it to create and consume more interconnected, richer, well-structured, and retrievable resources can have a direct impact on an organization’s profits and performance. Because when everything is connected, elements combine more easily, unite, are repositioned, and ultimately become comprehensible.

Structure and components of semantic metadata

Semantics therefore look for meaning through relationships, in order to translate it into a language that the machine will understand, so as to reach the point where it can draw conclusions by itself. To be able, that is, to interpret the lines of code it “reads” (: has as input), based on their interconnectivity with other lines of code (: digital representation of relationships) and to extract new lines of code (: digital representations of new relationships), which emerge from the previous ones, etc.

All of this based on a simulation whose complexity can be “extracted” from the objects and their relationships, since this calculation is limited to the capabilities of machines whose core “thinking” simplifies everything to 0s and 1s. Until, of course, quantum computers come into broader operation, but that is another topic.

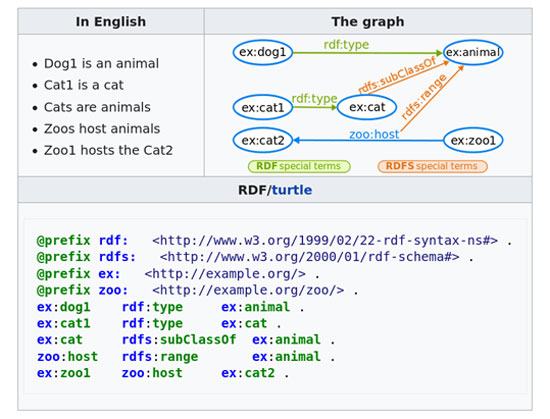

With this simplification that machines make internally, we will make a general reference to the way semantics are implemented in practice; to the way they try to organize data and form relationships between them.

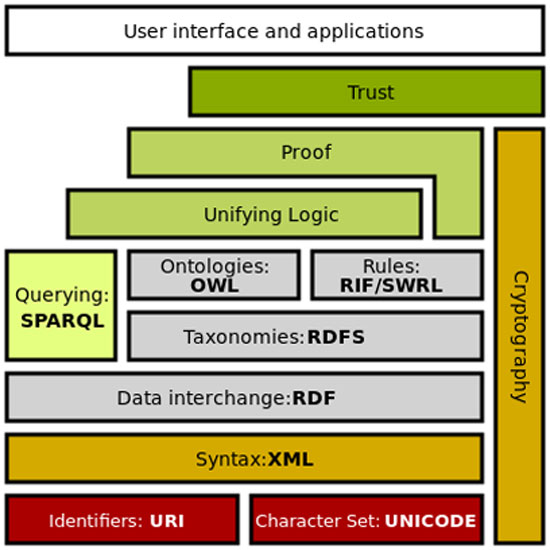

The standards for semantics have been designed and defined by the “World Wide Web Consortium” (W3C), the main international standards organization for the internet. The same organization is the one that has formulated the standards on which the Internet operates (HTTP, HTML, etc.). The basic “components” of semantics are as follows:

RDF Schema, a set of categories with certain properties that use the RDF knowledge representation data model, provides basic elements for describing ontologies. They can be stored in “triples”: specially designed databases for storing and retrieving “triples” through semantic queries. A “triple” consists of subject-predicate-object. For example, “John is 40” or “John knows George”.

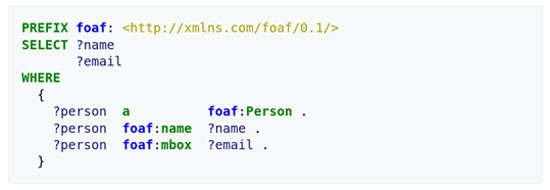

Subsequently, semantic queries for retrieving information from RDF are performed using the SPARQL language, which is like all information retrieval languages from databases (e.g., SQL), but specialized in retrieving semantic metadata.

With the above two technologies, metadata is stored and searched using “semantic terms”; in a way that includes their relationships. Based on this, it is possible to create “ontologies”, which is a representation of the names, definitions, properties, concepts, and entities that exist in one or more domains, as well as their relationships. Simply put, an ontology is a way to show the properties of a subject area and how they relate, defining a set of concepts and categories that represent the topic.

The definition of “ontology”, as far as computer science is concerned, was first given by the American Thomas Gruber5 in 1992, and we update it for 2009. We translate the relevant text, since the concept of “ontology” lies at the core of semantics functionality.

Ontology6

Definition

In the context of computer and information sciences, an ontology defines a set of primitive representations with which a domain of knowledge or reasoning can be modeled. The representative primitives are usually classes (or sets), attributes (or properties), and relations (or relationships between members of the class). The definitions of the representative primitives include information regarding their meaning and constraints on their logically consistent application. In the context of database systems, an ontology can be considered as a level of abstraction of data models, analogous to hierarchical and relational models, but intended for modeling knowledge regarding individuals, their attributes, and their relationships with other individuals. Ontologies are typically described in languages that allow abstraction from data structures and implementation strategies. In practice, ontology languages are closer in expressive power to first-order logic than the languages used for database modeling. For this reason, ontologies are said to reside at the “semantic” level, while database schemas are data models at the “logical” or “physical” level. Due to their independence from lower-level data models, ontologies are used to integrate heterogeneous databases, enabling interoperability between different systems and the specification of interfaces to cognitive services independent of implementation. In the classification of Semantic Web standards technology, ontologies are referred to as a distinct layer. Moreover, there are now languages and a variety of commercial and open-source tools for creating and processing ontologies.

Historical background

The term “ontology” originates from the field of philosophy that deals with the study of “Being” or existence. In philosophy, one can speak of an ontology as a theory of the nature of existence (e.g., Aristotle’s ontology provides primitive categories, such as substance and quality, which are supposed to account for everything that “Is”). In computer and information science, ontology is a technical term that denotes an artifact designed for a purpose: to allow the modeling of knowledge about some domain, real or fictional.

The term was adopted by early artificial intelligence researchers, who recognized the possibility of applying mathematical logic and argued that they could create new ontologies as computational models that allow certain kinds of automated reasoning. In the 1980s, the artificial intelligence community used the term ontology to refer both to a theory of a structured world (e.g., of simplified physics7) and as an element of knowledge systems.8 Some researchers, drawing inspiration from philosophical ontologies, regarded computational ontology as a kind of applied philosophy.

In the early 1990s, an effort to create interoperability standards identified a technological taxonomy that characterized the ontological level as a standard component of knowledge-based systems. A widely referenced website and a document9 related to this effort is credited with a careful definition of ontology as a technical term in computer science. The document defines ontology as a “clear specification of a conceptualization,” which in turn consists of “the objects, concepts and other entities that are supposed to exist in the area of interest and the relationships they maintain among themselves.” While the terms “specification” and “conceptualization” have generated much discussion, the key points of this definition of ontology are

- An ontology defines (specifies) the concepts, relationships, and other distinctions related to modeling a domain.

- The specification takes the form of definitions of the representative vocabulary (classes, relationships, and so forth), which provide concepts for the vocabulary and formal constraints on its coherent use.

An objection to this definition is that it is overly broad, allowing a range of specifications from simple glossaries to entire logical theories. However, this also applies to data models of any complexity. For example, a relational database consisting of a single table with only one column remains an entity of the relational data model. Taking a more realistic view, one could say that an ontology is a tool and product of engineering and is therefore defined by its use. From this perspective, what matters is the use of ontologies to provide the presentation mechanisms by which models can be created in knowledge bases, queries can be submitted to knowledge-based services, and the results of such services can be displayed. For example, integrating semantic tools into a search service might simply provide a glossary of terms with which to formulate search queries, and this would function as an ontology. On the other hand, the current W3C Semantic Web standard proposes a specific formalism for encoding ontologies (OWL)10, in various versions that differ in expressive power. This reflects the intention that an ontology is a specification of an abstract data model that is independent of its specific form.

Scientific basic principles

The ontology is discussed here in the applied context of software and database engineering, but it also has a theoretical basis. An ontology defines a vocabulary with which claims can be made, which may be inputs to or outputs from “knowledge agents” (e.g. a software program). As an interface specification, the ontology provides a communication language for the agent. An agent that supports this interface is not required to use the terms of the ontology as its internal encoding of knowledge. However, the definitions and formal constraints of the ontology impose limitations on what can be meaningfully stated in this language. Essentially, commitment to an ontology (e.g. supporting an interface using the ontology’s vocabulary) requires that statements made at the inputs and outputs be logically consistent with the ontology’s definitions and constraints. This is analogous to the requirement that the rows of a database table (or information insertion statements in SQL) must be consistent with integrity constraints, which are declared explicitly and independently of internal data formats (stm: referring to classical non-semantic databases).

Similarly, although an ontology must be formulated in some representation language, it is intended to have a semantic level specification – that is, to be independent of the strategy or application of data modeling. For example, a conventional database model can represent the identity of individuals using a primary key that assigns a unique identifier to each person. However, the primary identifier key is an artifact of the modeling process and does not denote anything in the domain. Ontologies are formulated in languages that are closer to the expressive power of logical formalisms, such as predicate logic.

This allows the ontology designer to be able to declare semantic constraints without being committed to a specific encoding strategy. For example, in standard ontology formalisms one could say that an individual is a member of a class or has some characteristic value without referring to implementation patterns such as the use of primary keys. Similarly, in an ontology one can represent constraints that hold relationships with a simple statement (e.g. A is a subclass of B), which could be encoded as a union of different keys in the relational model.

The mechanics of ontology deal with making representative choices that reflect the relevant distinctions of a domain at the highest level of abstraction, while still being as clear as possible regarding the concepts of the terms. As with other forms of data modeling, knowledge and skill are required. The legacy of computational ontology in philosophical ontology is a rich body of theory on how to make ontological distinctions in a systematic and coherent way. For example, many of the notions of “formal ontology” based on understanding the “real world” can be applied when creating computational ontologies for data worlds. When ontologies are encoded in formal formalisms, it is also possible to reuse large, pre-designed ontologies of human knowledge or language. In this context, ontologies incorporate the results of academic research and offer a functional method for transforming theory into practice in database systems.

Semantic Web: the semantic web

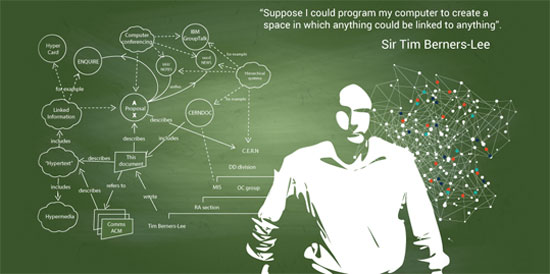

While the technology of semantic metadata can stand on a computer, in a database or in a datacenter, be part of a closed network (e.g. of a university) or of a research center, its real capabilities unfold when it is left “free” in the ocean of cyberspace. There it essentially fulfills the dream11 of every “cyber-progressive” for an interoperability of everything; like that of the creator of the World Wide Web (WWW) Tim Berners-Lee. Below is a relevant interview with him in BusinessWeek, published by Bloomberg:12

Tim Berners-Lee has not at all lost touch with the World Wide Web. Having invented the Web in 1989, he is now working on ways to make it much smarter. Over the past decade, as director of the World Wide Web Consortium (W3C), Berners-Lee has been working on an effort called the “Semantic Web.” At the heart of the Semantic Web is technology that helps people find and correlate the information they need, whether that data resides on a Web site, in a corporate database, or in some software.

The Semantic Web, as Berners-Lee envisions it, represents such a profound change that it isn’t always easy for others to grasp. It’s not the first time he has faced this challenge. “It was very difficult to explain the Web before people got used to it, because they didn’t even have words like click and navigate and website,” says Berners-Lee. In a recent conversation with BusinessWeek.com writer Rachael King, Berners-Lee discussed his vision for the Semantic Web and how it could change the way companies operate.

It appears that one of the problems that the Semantic Web can solve is unlocking information in various silos,13 in different software applications and in different locations that cannot currently be easily connected.

Exactly. When you use the word “silo,” this is the word we hear when someone in the business talks about the problem of incompatibility. Different words for the same problem: business information within the company is managed by different types of software, and each time we have to address a different person and learn a different program to use it. Any business executive should really be able to ask a question that involves connecting the data of the entire organization, be able to run a company effectively, and especially be able to respond to unexpected events. Most organizations do not have this ability to connect all the data together.

Even external data can be integrated, as I understand it.

Absolutely. Whoever makes real decisions uses data from many sources, produced by many kinds of organizations, and this becomes an obstacle. We tend to use spreadsheets to do this and people have to put the data into computational sheets, which they prepare with great effort. In a way, the Semantic Web looks somewhat like all the databases out there as one large database. It is difficult to imagine the power we will have when so many different kinds of data are available.

It seems to me that we are “drowned” in data and this could be a good way for us to be able to find the data we need.

When we can treat something as data, your question can be much more powerful.14

In your talk at Princeton last year, you said that you might have made a mistake in naming it “Semantic Web.” Do you think the name confuses some people?

I don’t think it’s a very good name, but we’re stuck with it now. The word semantics is used by different groups and means different things. But now people understand that the Semantic Web is the Data Web. I think we could have called it the Data Web. It would have been simpler. I faced many problems naming the World Wide Web “www” because it was so long and difficult to pronounce. In the end, when people understand what it is, they realize that it connects all applications together or gives them access to data across the entire company, when they see some general applications of the Semantic Web.

Some of the first works with the Semantic Web appear to have been done by government services such as the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). Why do you think the government has adopted this technology early on?

I understand that DARPA had its own serious problems with huge amounts of data from all different sources for every kind of thing. So, they correctly saw the Semantic Web as something that directly aims to solve the problems they had on a large scale. I know that DARPA also subsequently funded part of the initial development of this technology.

You have mentioned the idea that the Semantic Web will facilitate the discovery of therapies for diseases. How will it do this?

So, when a pharmaceutical company examines a disease, they take the specific symptoms associated with specific proteins within a human cell that can lead to these symptoms. Thus, the art of finding the drug is finding the chemical substance that will affect the bad things that are happening and encourage the good things that are happening within the cell, which includes understanding genetics and all the connections between proteins and disease symptoms.

It also requires us to examine all other connections, whether there are federal regulations regarding the use of the protein and how it has been used previously. We have governmental regulatory information, clinical trial data, genomic data and proteomic data, all located in different departments and different software. A scientist who undertakes this creative process of exchanging ideas, in order to find something that could potentially cure the disease, must keep everything in mind at the same time or be able to explore all these different axes in a connected way. The Semantic Web is a technology designed to do exactly that – to break down the boundaries between silos, to allow scientists to explore hypotheses, to see how things are connected in new combinations that they had never dreamed of before.

The Semantic Web makes it much easier to find and correlate information about almost anything, including people. What will happen if this information falls into the wrong hands? Is there anything that can be done to protect privacy?

Here at MIT, we do research and build systems that recognize social issues. They have awareness of privacy constraints, appropriate uses of information. We believe it is important to create systems that will help do the right thing, but we also create systems that, when they take data from many, many sources and combine them and allow us to reach a conclusion, are transparent in the sense that we can ask them what their decision was based on and that we can go back to check if they are actually suitable for use and if we feel they are reliable.

The development of Semantic Web standards took years. It took so long because the Semantic Web is so complicated;

The Semantic Web is not inherently complicated. The language of the Semantic Web, at its heart, is very, very simple. It has to do with the relationships between things.

A (new) example

Berners-Lee’s “vision” of facilitating the discovery of therapies through semantics is already a reality. The case of Astra Zeneca is an example where semantic data becomes practice in research for new drugs and therapies. We translate from a relevant document:

For the purposes of collecting information from a wide range of biomedical data sources, Astra Zeneca found the solution in Linked Data. The company’s researchers needed a mechanism that would allow them to extract all the data scattered across different related resources and identify visible (direct) and invisible (distant) relationships between biomedical elements studied during pharmaceutical research.

By creating an interactive relationship search platform, called Linked Life Data, the biopharmaceutical company was able to obtain high-quality research data from their unstructured documents. The platform integrated more than 25 data resources and combined more than 17 different biomedical entities: genes, proteins, molecular functions, biological processes, molecular interactions, cell locations, organisms, organs/tissues, cell lines, cell types, diseases, symptoms, drugs, drug side effects, publications, etc.

The Linked Life Data platform was able to identify clear relationships between elements by categorizing them into ontologies. It also mined unstructured data to detect relationships not apparent at first reading. It was a tremendous help to researchers in gaining an overall picture regarding the creation or extension of a particular theory, hypothesis testing, and making informed claims about which relationships are causal and exactly how the correlation is causal.

Instead of a conclusion

The distance between proving that a person is not a robot and proving that a machine is not a robot is shrinking. Not because machines are becoming smarter, but because human thought and the human body are being dissected, categorized, “timed,” and translated, so that they can be processed by machines. This process does not result in the development of a “human machine,” but rather a “mechanized humanity.” And it has its own genealogy.

We will conclude with a small excerpt from the notebooks for worker use no. 3, “the mechanization of thought”, referring there for a broader critical approach:

The conception of language as a system is a kind of “paradigm shift” in linguistics, which Saussure proposes and advances in the second half of the first decade of the 20th century. However, the idea of “system” comes from the positive sciences! It has already been established in chemistry, biology and physics of the 19th century: in thermodynamics, in mechanics…

Saussure’s bold move, then, is to take an idea already tested either with a mechanical or organic flavor, the idea of the system, and apply it to “something” (the analysis of language) that until then had a historical-analytical direction. Saussure (in the “lectures on general linguistics”) is enthusiastic about this transposition. And categorically:

“… A language constitutes a system… this system is a complex mechanism; one cannot master it except through thought; and those who make daily use of this mechanism profoundly ignore it…”

The above position is fundamental and starting in the way Saussure proposes the scientific analysis of languages. And it is deeply Taylorist, even though he never met or heard anything about (his contemporary) Frederick Winslow Taylor:

a) language is a mechanism and indeed a complex one;

b) those who “use” this “complex mechanism” (by speaking or writing) do NOT know it!Without a trace of exaggeration, we would say that Saussure is the first (many others will follow) to conceive of the scientist himself, the linguist scientist, as a m e c h a n i c of language. The linguistic system was a conception that today seems commonplace, but at the time was both innovative and impressive. And this is because, from the moment language is understood as a system, the “components of the system” (words, meanings, expressions), almost infinite in quantitative terms, must be “analyzed” in a qualitative way; if the “mechanic of language” is to “tame the mechanism.” For this reason, new analytical tools will need to be invented…

Wintermute

- The Turing test is a procedure by which it is examined how much a computer can simulate human intelligence. The test is conducted in the form of written question-and-answer exchanges between a human and two hidden “conversationalists”, one human and one computer. The evaluation is based on the human’s ability to recognize which is the human and which is the machine. ↩︎

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Knowledge_representation_and_reasoning ↩︎

- One step closer to intertwingularity: Semantic Metadata – https://www.ontotext.com/blog/semantic-metadata/ ↩︎

- Intertwingularity is a term coined by Ted Nelson to express the complexity of interactions in human knowledge. Nelson wrote in Computer Lib / Dream Machines (Nelson 1974): “Everything is deeply interconnected. In a sense, there are no “subjects” at all. There is only knowledge, since the connections between the myriad topics of this world simply cannot be clearly separated.” ↩︎

Thomas Gruber is also the co-founder of Siri Inc, the company that built the digital personal assistant Siri, which was acquired by Apple in 2010 and now exists on every one of its devices. In his rich biography, one can find his contributions to the field of artificial intelligence and user interface, his collaborations with many companies as well as with DARPA. In recent years he has been promoting the idea of “Humanistic AI”. For more, see also his related TED talk.

↩︎- Ontology, by Tom Gruber, in the Encyclopedia of Database Systems, Ling Liu and M. Tamer Özsu (Eds.), Springer-Verlag, 2009. ↩︎

- Naïve physics: folk/simplified physics is the uneducated human perception of basic physical phenomena. In the field of artificial intelligence, the study of simplified physics constitutes part of the effort to formalize human common knowledge. ↩︎

- Knowledge-based system: a computer program that reasons and uses a knowledge base to solve complex problems. ↩︎

- Toward principles for the design of ontologies used for knowledge sharing (https://tomgruber.org/writing/onto-design.htm) ↩︎

- Web Ontology Language (OWL): The Web Ontology Language is a family of knowledge representation languages for authoring ontologies on the Semantic Web. ↩︎

- Which also requires the critical infrastructure for a complete datafication: smart devices everywhere, Internet of Things (IoT), and a capable network to “carry” the volume (5G, 6G, etc.). ↩︎

- Q&A with Tim Berners-Lee – The inventor of the Web explains how the new Semantic Web could have profound effects on the growth of knowledge and innovation [Bloomberg – April 9 2007] ↩︎

Stm: Silos are structures used for feeding (loading, unloading) and bulk storage of solid materials. The term silo comes from French silo, which in turn comes from Spanish silo, “underground storage,” with possible origin from Latin sirus, which derives from ancient Greek σιρός, “container or pit for storing grain.” In the present context, it is used metaphorically for digital storage spaces.

↩︎- Stm: It means when there is the possibility to organize the data as such and not simply as records in a database. That is, when they acquire their semantic interconnection. Then the information search queries will be more powerful. ↩︎