In its complaint, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) describes how, with a data sample obtained from Kochava, it was possible to identify a device that visited a women’s reproductive health clinic and then to locate this phone at a residence.

vice.com 29/8/2022

Kochava is a company that most people probably don’t know, but it’s one of those companies that “know” a lot about most people. Its main business is data trading and it belongs to the category of companies called “data brokers”. While the companies that come to mind regarding privacy and personal data issues on the internet are companies like Facebook and Google – and rightly so – an entire network of data buying and selling takes place “behind the scenes”, by companies like Kochava, which collect data packages from various sources and offer them on the “free” market.

The complaint filed by the U.S. Federal Trade Commission states1 that: “The defendant’s violations (Kochava) relate to the acquisition of consumers’ geolocation data and the sale of such data in a format that enables entities (i.e., buyers) to track consumers’ movements to and from sensitive locations, including, among others, locations related to medical care, reproductive health, religious worship, temporary mental health shelters, such as shelters for the homeless, victims of domestic violence, or other at-risk or recovering populations.”

But how can a company know all these things? At first glance, the ability to collect the locations and movements of a mobile phone could provide an approximation of the user’s health status, for example, if they visited a clinic. But what did they do there, how did it “leak”? In the case that someone publishes more information about their life on a platform, e.g. Facebook, it is obvious that this “knowledge” can be combined with the mobile phone’s locations. However, this does not always happen and the “digital traces” we leave by browsing our lives are not necessarily – nor feasible to some extent – to be collected by a specific platform/company. Also, some platforms/companies may want information that another specific platform/company has. This is where data brokers come into play, or otherwise, we could say, “surveillance intermediaries”.

Their main objective is the collection of many (all?) types of data (names, addresses, phone numbers, emails, ages, gender, social security numbers, income and real estate, education, profession, etc.) from various sources (social media, internet browsing history, online purchases or with credit card in physical stores, public documents such as from registries, courts, etc.). Their sources may be the “original” ones where the data exists or other data brokers, thus creating a complex web of data exchanges. There are various types of “intermediaries” and several ways in which they collect data, however a separate report will be needed for all these. Here we will focus on the “creation of profiles” of potential voters by party campaigns in collaboration with data brokers.

Privacy International states the following:2

There is a complex and opaque corporate ecosystem behind targeted online political advertising. In this, it’s not just the profiles on Facebook and Twitter – data brokers and data analysis companies are all part of this process. Data analysis companies are used directly by political parties contesting elections to conduct online campaigns. The details are often unclear – exactly who these companies work for, what they do and how they do it is often a well-kept secret. What is clear is that there are thousands of companies whose business model is to exploit the data that people leave on the Internet in such a way that personal information about an individual’s beliefs, habits and behavior can be better understood and used by political parties to send targeted political messages to these individuals.

[…]

The existing data and advertising ecosystem has targeted content for specific audiences. This is common and allows companies not only to reach very specific individuals, but also at specific times and places.

For political campaigns, this has many unique advantages. Unlike posters or television political advertisements, which are public by definition, [data-driven] online campaigns can display different ads and different content to different people. This means they can make different promises or even contradictory claims with minimal oversight or accountability. This has removed political advertising from the public sphere – we can all see posters/billboards on the street or ads on television and to some extent call political parties to account for their messages and how much they spend. However, when only a few people see a message or everyone sees something different, this makes the process less accountable. […]

The term “profiling” is described in the European General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). It is defined as “any form of automated processing of personal data consisting of the use of personal data to evaluate certain personal aspects relating to a natural person, particularly for analyzing or predicting aspects concerning that person’s job performance, economic situation, health, personal preferences, interests, reliability, behavior, location or movements.”

In short, this means that organizations, many of which you have never heard of, are able to learn about your habits, personality, sexual interests, political beliefs, and much more in order to make predictions about your personality and behavior. This is true even if you have not shared this information with them. This is particularly concerning when sensitive information, such as political beliefs or personality traits, is inferred from completely unrelated data through “profiling.”

Party election campaigns have always been an effort of “persuasion and deception,” just like product marketing, and both used the tools that were available at the time. The text we translate next was written in 2014, when Twitter was an “emerging platform,” but it presents in a useful way the qualitative change taking place through the use of big data in these efforts—regardless of one’s opinion on “representative democracy”—highlighting certain key points that are crucial for understanding the centrality/criticality of data in the new capitalist model. It mainly shows that, while the common perception is that data (and their storage/processing) is like the classic “filing,” just in larger quantities stored on computers instead of on paper, and that merely some correlations are made automatically and quickly, the reality is far removed from this.

Wintermute

The mechanics of the commons: Big data, surveillance and “computational politics”3

The emergence of networked technologies gave hope that interaction in the public sphere could help limit or even treat some of the ailments of late modern democracies. Unlike broadcast technologies (radio, television), the Internet offers extensive possibilities for horizontal communication among citizens, while drastically reducing the cost of organizing and accessing information. Indeed, the Internet has been a crucial tool for many social movements.

However, the Internet’s tendency to “empower” citizens is neither straightforward nor clear-cut. The same digital technologies have also created a data analysis environment that favors the powerful, data-rich established entities and the technologically savvy, especially within the framework of party campaigns. These opposing trends specifically arise from the increased exploitation of big data, that is, from very large sets of information data derived from online footprints and other sources, along with analytical and computational tools.

Big data is usually “welcomed” for its ability to add to our knowledge in new ways and enrich our understanding. However, big data should also be examined as a political process involving issues of power, transparency, and surveillance. In this article, I argue that big data and related new analytical tools encourage a more effective—and less transparent—”engineering of consent” in the public sphere. As a regulative (but contested) ideal, the public sphere, as envisioned by Habermas, is the site and place where rational arguments about public matters can take place, especially those concerning governance and citizenship, free from the constraints of status and identities. The public sphere should be considered simultaneously a “regulative ideal” as well as an institutional analysis of historical practice. As actual practice, the public sphere refers to “places”—intersections and commons—where these social interactions occur and which are increasingly online. This turn toward a partially online public sphere, which has enabled the observation, monitoring, and collection of these interactions into large datasets, has led to computational politics, which is the focus of this article.

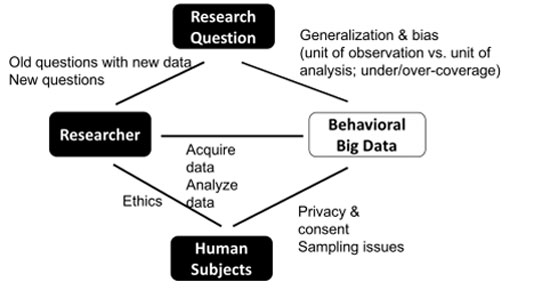

Computational politics refers to the application of computational methods to large datasets derived from online and offline data sources in order to achieve outreach, persuasion, and mobilization for electoral purposes, the promotion or opposition of a candidate, a policy, or legislation. Computational politics is based on the behavioral sciences and is improved by using experimental approaches, including online experiments, and is often used to create profiles of people, sometimes at a collective level but mainly at an individual level, and to develop methods of persuasion and mobilization that can also be personalized. Thus, computational politics is a set of practices the evolution of which depends on the existence of big data and accompanying analytical tools and is defined by the significant information asymmetry – those who hold the data know far more about individuals, while individuals do not know what data holders know about them.

While computational politics in its current form includes new applications, the historical trends discussed in this article predate the spread of the Internet. In fact, there was already significant effort underway to use big data for marketing purposes, and the progress of using these marketing techniques for politics—and the “selling of a president”—clearly reflects long-term trends. However, computational politics introduces significant qualitative differences in this long journey of historical trends. Unlike previous data collection efforts (for example, magazine subscriptions or purchases of specific types of cars) that required complex, circular conclusions regarding their meaning (does a magazine subscription really signal a voter preference?) and allowed only broad profiling overall, this data [big data] now provides a significantly more personalized profile and modeling, a much greater depth of information, and can be collected invisibly, surreptitiously, and attributed at an individualized level.

Computational politics transforms political communication into an increasingly personalized, private transaction and therefore fundamentally reshapes the public sphere, first and foremost by making it less and less public, as these approaches can be used both for profiling and for individual interaction with voters outside the public sphere (e.g. a Facebook ad targeting a specific voter, who is the only one who sees it). Overall, the impact is less like increasing the power of a magnifying glass, and more like repurposing the lens, combining two or more lenses to create fundamentally new tools, such as the microscope or telescope, turning invisible objects into objects of scientific research and manipulation.

The impact of big data on the public sphere through computational politics operates via multiple interconnected dynamics, and the purpose of this work is to define, explain, and explore them both individually and within the framework of this interweaving. First, the rise of digital mediation of social, political, and economic interactions has resulted in an exponential increase in the volume and type of available data, especially in large organizations that can economically afford access. Second, emerging computational methods allow political targeting to move beyond group-based aggregate analysis to modeling specific individuals. Third, such modeling enables acquiring insights about an individual without directly posing questions to that person, thus opening the door to a new wave of techniques based on “covert tactics” and opacity. Fourth, advances in behavioral sciences have led to a departure from “rational actor” models toward more sophisticated and realistic models of human behavior. Combined with the other dynamics described here, these models allow for improved network-based social engineering. Fifth, digital networks enable these methods to be experimentally tested in real-time with immediate implementation, adding a level of dynamism and speed that was not feasible in the past regarding shaping the public sphere. Sixth, the data, tools, and techniques involved in these methods require access to proprietary, costly data and are driven by opaque algorithms—opaque algorithms refer to “black box” algorithms, the functions of which are exclusive and unknown, and most of which are controlled by the few major Internet platforms [e.g., Google, Facebook, etc.].

[…]This work focuses on the intertwined dynamics of computational politics and big data, emphasizing their impacts on power, politics, and the public sphere, and engages in empirically-based, conceptual theory required for both conceptual and empirical research. While many of the aspects explored here apply to commercial, corporate, and other sectors, albeit with different emphasis, issues of computational politics warrant independent analysis as assumptions are not uniform, and given that political practice is central to citizen issues.

The commons machine: from radio-television to the Internet

The discussion about meaningful participation in governance in a society that is too large for frequent and direct face-to-face interaction – that is, any social organization larger than a small village or a band of hunters/gatherers – has a long history, with written records dating back at least to the time of Plato and Aristotle. At its core, this discussion concerns whether, in large societies where the concentration of power and authority appears inevitable, the citizen – within the gradually expanding, historically variable definition of the term – can ever be fully equipped to undertake or understand all the complex decisions required for governance. And furthermore, what can keep those in power in check, so that they do not secure the perpetuation of their own dominance.

Plato called for kings to be philosophers, so as to govern justly for the good of society, but not necessarily by being sincere or accountable. A modern embodiment of Plato’s call for powerful but benevolent “philosopher-kings” emerged in the early twentieth century in the Lippmann-Dewey discussions (Dewey, 1927; Lippmann, 1925). Walter Lippmann expressed pessimism about the likelihood of the public being genuinely capable of governing and argued that the powerful would always be able to manipulate the opinions, beliefs, and ultimately the electoral behavior of ordinary citizens. They would be the “social engineers,” in Karl Popper’s terms, those who would manipulate the public to achieve their own goals. John Dewey, however, believed that it was possible to build social and political institutions—ranging from a free press to a genuinely enriched education—that would expose and counter the manipulations of the powerful and allow for substantial self-governance by an informed and robust body of citizens. Although both Dewey and Lippmann were concerned about the powerful controlling the public, neither had experienced the full force of mass media such as radio and television.

The rise of broadcast media changed the dynamics of politics in fundamental ways. The pioneer of public relations Edward Bernays explained the root of the problem in his famous article “Engineering of consent” where, discussing the impact of broadcasting on politics, he argued that the cliché “the world has become smaller” was actually false. The world is in fact much larger and today’s leaders, he pointed out, are more distant from the public compared to the past. The world seems smaller partly because modern communication allows these leaders, more powerful than ever, to communicate and persuade huge numbers of people and to “engineer their consent” more effectively.

Bernays saw this as an inevitable part of every democracy. He believed, like Dewey, Plato, and Lippmann, that the powerful had a structural advantage over the masses. However, Bernays argued that the techniques of the “engineering of consent” were neutral, irrespective of the message. He encouraged well-intentioned, technologically and empirically competent politicians to become “philosopher-kings” through manipulation techniques and the engineering of consent:

«The techniques can be reversed. Demagogues can use the techniques for anti-democratic purposes with as much success as those who use them for socially desirable purposes. The responsible leader, in order to achieve social goals … must use his efforts to acquire the operational expertise of the engineering of consent and displace his opponents towards the public interest.»

Bernays advocated for the study of the public through opinion research and its control through the management of communication and the media. The opinion control techniques adopted by Bernays became the bread and butter of partisan campaigns in post-war Western countries. At its core, this is guided by “public opinion research” which seeks to understand, categorize and characterize the public and their diverse opinions, as the key to effective “persuasion” – whether marketing a politician or a soft drink. Shortly after public opinion research began to infiltrate politics, the cultural critic Adorno characterized the forms of “classification, organization and labeling” as a form of propaganda in which “something is provided for everyone so that no one can escape.” In other words, Adorno feared a public sphere in which politicians would accurately identify all voter subcategories and offer each one a pleasant message.

However, messaging and mobilization based on such subcategorization has inherent limitations in the method, as each categorization conceals different qualities/varieties. The correspondence between demographic or political profiles and a specific individual is, at best, probabilistic and often quite convoluted. During the broadcast television era, targeting was generally oriented, because the television audience was measured in broad demographic terms. The best that aspiring marketers could do was to define probable niche audiences, such as “soccer-mom watchers,” by gender and age, and to target programs to that gender and age group. Because the audience could not be strictly defined, messages also had to be broader. “Soccer-mom watchers” certainly encompass diverse political opinions and personalities. Many who are exposed to advertisements would not fit the target group, and many members of the target group would be excluded. Research has shown that such political advertisements on television shows remained largely ineffective in shifting the balance among existing candidates, at least compared to more structural factors such as the unemployment rate or economic growth.

Similarly, almost all voter mobilization and turnout campaigns traditionally rely on the regional level simply and solely because demographic data were available at this level. However, regional data are probabilistic since no region votes uniformly for a single party, therefore campaigns tend to channel resources into a specific region hoping that they will mobilize more supporters than their opponents and that their efforts will not worsen too many supporters elsewhere. Party campaigns, in turn, ignore regions that contain many of their own voters, but fewer than those of their opponent.

It is no surprise that targeting individuals as individuals and not as members of various broadly defined demographic categories has long been the holy grail of political campaigns. Such efforts have been underway for decades. By collecting information from credit cards, magazine subscriptions, voter registration records, and other sources, political parties have gathered as much information as possible about all individual voters. However, until recently, data collection at the individual level was fragmented and piecemeal, and targeting still relied on demographic groups, which were simply based on richer personalized data than before. Much of this has changed with the rise of the Internet, which significantly increases both the type and quantity of individual data available, as well as computational analysis, enhancing the information that can be gathered from these sources.

New dynamics of persuasion, surveillance, political campaigning and social engineering

The recent rise of big data and computational techniques is once again changing political communication with citizens. If twentieth-century consent engineers had magnifying glasses and baseball bats, those of the twenty-first century have acquired telescopes, microscopes, and scalpels in the shape of algorithms and analytics. In this section, I examine six interrelated dynamics that create a new environment of surveillance and social engineering.

- Big Data

The advent of digital and networked technologies has caused an explosion in the quantity and variety of data available for every individual, as well as in the speed at which this data becomes available. These large collections of data, referred to as big data, are not simply data of the old kind. Rather, in some way, their results resemble the invention of the microscope that makes visible what was previously invisible, as well as visible in other ways or like a telescope that allows the observer to “zoom out” and observe at a different scale, often with a loss of the detail and individuality of the data, but with very powerful aggregate results. While the above do not fully capture their new impacts, big data, like the microscope and telescope, threaten to overturn our understanding of multiple fields and transform the practice of politics.

What has changed is not only the depth and breadth of available data: the fundamental nature of the data available for collection has undergone significant change. In the past, data collection was primarily “passive” (questions answered voluntarily, such as in surveys), supplemented by a layer of “latent data,” which consists of data that exist as traces of the actions we perform as we go about our lives. In the pre-digital era, such latent data were limited—financial transactions, magazine subscriptions, credit card purchases. Political campaigns faced the challenge of inferring what such a transaction meant. Does a subscription to Better Homes & Gardens indicate partisan affiliation? Does it reflect a stance on progressive taxation? The answer was often “perhaps,” but it was weak. Such data provided some correlational guidance at the group level, but did not allow for precise individual targeting.

The rise of the Internet as a social, urban and political space has caused tremendous growth in a different category of data that are often called “user-generated data”. Part of this growth is due to latent data (latent data or metadata4). Electronic transactions carried out for a wide variety of purposes now leave behind valuable footprints. Latent data arise as the user goes about his daily life, say, buying products and participating in social media. The footprints he leaves behind, however, carry significant information and include his actual conversations. Therefore, in contrast to the explicit process by which a respondent is asked by a pollster about his choices and the answer is recorded, campaigns can now record real statements of people as they talk about a wide variety of topics of interest to them. Data brokers are increasingly scraping and examining user behavior in these environments and collecting responses, which they combine with huge amounts of other online and offline data about the individual. This type of content created by users is directly semantic and instead of complex conclusions, such data provide a deeper and more direct picture of a person’s views, attitudes and behaviors (through computational methods discussed below).

The environment in which user-generated data is created has undergone dramatic change. Even just eight years ago, when the Internet was already widely prevalent, political campaigns had to resort to some degree of trickery to compel users to provide data/content. Howard (2006) documents how a political firm secretly operated a discussion forum that provided participants with aggregated voting data of politicians mainly in order to gain access to participants’ discussions. People had to be lured into “producing” user-generated data. These days, such data is voluntarily and widely produced by individuals themselves as a byproduct of digitally mediated citizen participation—in other words, people comment and discuss politics on general-purpose digital platforms, and this digital mediation of their activities leaves behind a treasure trove of data collected by companies and data brokers.

Moreover, the quantitative depth of big data composed of online footprints is exponentially greater than pre-digital data. A large commercial database can easily contain thousands of data points for each individual—a recent report found that some data brokers had 3,000 individual data points per person and were increasing them at a rapid pace. The volume and variety of this kind of big data are qualitatively different. If nothing else, the problem of data analysis today is that there is too much data, too “deep” and too diverse. However, the rise of computational methods and models is quickly responding to the challenge of turning this flood of data into useful information in the hands of political campaigns and others.

- Evolving computational methods

All this data is useless without the techniques for extracting useful information from the dataset. The computational methods used by political campaigns depend on multiple recent developments. First, technical advances in storage systems and databases mean that large quantities of data can be stored and used. Second, new techniques allow the processing of semantic data (semantics5), that is, unstructured information contained in the natural language used by the user, such as conversations—in contrast to already structured data such as a financial transaction, which comes in the form of pre-organized fields. Third, new tools allow the examination of human interactions through a structural lens using methods such as social network analysis. Fourth, the scale of the data enables new kinds of correlational analyses that previously would have been difficult to imagine.

Firstly, given the volume of data being generated, even simple storage was a challenge and required the development of new methods. On YouTube, videos with a total duration of 72 hours are uploaded every minute. Since last year, Facebook has been processing approximately 2.5 billion pieces of content, 2.7 billion “likes”, 300 million photos, and a total of 500 terabytes of data daily. Handling such large datasets has recently become easier through the development of techniques such as “Hadoop clusters” which provide a shared-storage system along with “Map Reduce” which provides the analytical layer that allows reliable and fast access to such large datasets. Facebook reportedly maintains its data in a 100 petabyte Hadoop cluster.

Second, new computational techniques allow the extraction of semantic information from data without the use of a army of human coders and analysts, as would be required by older techniques. Techniques that automatically “score” words to create estimates of ideological content of texts and sentiment analysis or group sentences into topics, allow a probabilistic but quite powerful method of categorizing an individual’s approach to a subject as represented in their textual statements, but without the expensive gaze of a human reading the actual content. Without these computational techniques, texts would have to be read and summarized by a large number of people. Even then, simply aggregating the results would be a challenge. While algorithms come with traps and limitations – for example, “Google Flu Trends” which was once hailed as a great innovation has been proven to produce misleading data – they can be useful for providing information that would otherwise be prohibitively expensive or impossible.

Third, the analysis of social networks, the roots of which go back to the sociology of the 1950s, has expanded significantly in utility and technical scope, allowing analysts not only to map people’s opinions, but also to place them within social networks. The expanded utility arose partly because network-form data has increased significantly due to online social networking platforms used for various purposes, including political ones. Previously, collecting social network information from people was a difficult and expensive effort and various biases and difficulties in retrieving social network information led to many challenges as even small social networks required hundreds of interviews where people were expected to report dozens, if not hundreds, of social ties. As one would expect, such research was always very difficult and was conducted only on small samples.

With the emergence of networks encoded by software, network analysis became possible without the difficult step of collecting information directly from individuals. Researchers also began to apply network analysis to broader topics where “connections” could be interpreted as “links” in a network – such as the blogosphere (with each link constituting a connection) or researchers’ bibliographic reference networks. Network analysis allows the identification of various structural characteristics of the network, such as “centrality,” clustering (whether there are dense, distinct groupings), bridges connecting clusters, and many others, which provide valuable political information about how to target or spread political material. For example, individuals with high centrality are useful disseminators of information and opinions, and once identified, they can be targeted by political campaigns as entry points into larger social networks.

Fourth, researchers can now search for “correlations” in these massive data sets in ways that would have been difficult to impossible before. This has led, of course, to many positive applications. For example, researchers began to detect drug interactions by examining Google searches for many drugs that match symptoms—an achievement that cannot practically be done otherwise, which would mean researching all users of all drugs for all side effects. However, for political campaigns, this also opens doors for better personalized identification of target individuals by examining or correlating their political choices with other characteristics. Given that data brokers have thousands of data points for nearly every person in the United States, these new computational methods are available to campaigns, with which they can analyze, categorize, and act on the electorate.

- Modeling

In this context, modeling is the act of extracting new information through analysis of data based on creating a computational relationship between underlying data and target information. Modeling can be much more powerful than the aggregate profile. The aggregate profile attempts to classify a user by placing them in a category with many others, combining available data. Someone who answered a survey question about environmental issues as “very important” to them, for example, is most likely an environmentally conscious voter. Combined with purchasing data (e.g., shopping at Whole Foods), a campaign can classify them as an environmentally conscious voter.

However, the emergence of large datasets containing real behavioral fingerprints and social network information—social interactions, conversations, friendship networks, reading and commenting history across various platforms—combined with advances in computational techniques means that political campaigns (as well as advertisers, companies, and others with access to these databases and technical resources) can model individual voter preferences and characteristics with a high level of accuracy and, importantly, often without posing a single direct question to the voter. Paradoxically, the results of such models may match the quality of answers that could only be extracted through direct questioning and far exceed the range of information that could be gathered about a voter through traditional methods.

For example, a recent article shows that the simple use of likes on Facebook is sufficient to accurately model and predict an impressive number of personal characteristics, such as “sexual orientation, nationality, religious and political views, personality traits, intelligence, happiness, substance use, parental divorce, age and gender.” Researchers’ models that used Facebook likes exclusively – a fraction of the data available to any data broker – correctly identified whether the Facebook user was heterosexual or not in about 88% of cases, predicted gender with about 95% accuracy, and detected any倾向 towards political parties with about 85% success. In other words, access to just a fraction of Facebook’s data, when processed through a computational model, largely allows Republicans and Democrats to be correctly delineated without examining any other database, voter registration records, financial transactions, or participation in organizations.

While parts of this example may seem insignificant, as some of them, such as age and gender, are traditional demographic characteristics and usually included in traditional databases, it is important to note that these are estimated through modeling and are not requested or observed from the user. This means that these features can also be modeled on platforms where anonymous or pseudonymous posts are the norm. This type of modeling also promotes information asymmetry between political campaigns and citizens. Campaigns “know” about every given voter, with voters having no idea about these background models.

Primarily, this type of modeling allows access to psychological characteristics that were beyond the scope of traditional databases, which are as intrusive as we could imagine. Personality traits such as “openness” or “introversion” or “neuroticism” are traditionally measured with surveys, which have been developed and validated by psychologists and used on large numbers of people for decades. Although these characteristics may be generalizations, they are significantly more detailed than the crude demographic data used by political advertisers (“soccer-mom fanatics”). Kosinski proved that models based on Facebook likes were as good as scientific scales. In other words, without asking a single question, researchers were able to model psychological characteristics with the same accuracy as a psychologist using a standardized, validated tool. Given that social media data has been used to accurately model characteristics ranging from suicide rates to depression in other emotional and psychological variables, and given that social media is simply one aspect of the information available for big data modeling, it is clear that political campaigns can have a much richer, more accurate classification of voters without even necessarily knocking on their door once to ask a question.

To understand why this is an important change, consider how different it is compared to the coarser and more basic profile that has been used in traditional polling research to identify likely voters. For decades, traditional polling organizations and political campaigns have tried to shape likely voters in their surveys with varying degrees of success. Campaigns don’t want to spend resources on individuals who are unlikely to vote, and pollsters need this information to properly weight their data. The question itself (“are you likely to vote?”) has not proven that useful, due to the well-known social desirability bias in responses: many reluctant voters declare their intention to vote. Previous voting records are also poor predictors—besides, there are many new voters entering the rolls. Gallup, whose likely voter model was long considered the gold standard, asks a series of seven questions covering intention, knowledge (where is your polling place?), past behavior, and indirect approaches (how often do you think about elections?). However, even with decades of expertise, Gallup missed election predictions due to its inability to accurately identify likely voters through these surveys. The seriousness of the situation was such that Gallup became a punchline: at the White House Correspondents’ Association dinner, President Obama made a predictable joke, followed by another joke about who didn’t see the [predictable] joke coming: “Show of hands? Only Gallup?” he quipped.

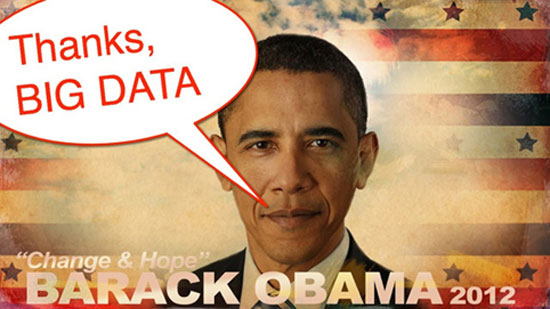

By contrast, during the 2012 elections, Barack Obama’s campaign developed a fairly sophisticated “likelihood to vote” model based on its datasets, which relied not only on polls but incorporated the kinds of data discussed in this article, and created a score from 0 (will not vote) to 100 (definitely will vote) for each potential voter. This resulted in a targeted, highly effective persuasion and turnout effort, which focused primarily on getting voters who were already Obama supporters to show up, rather than spending significant effort trying to convince voters who would not end up voting. This left Romney’s campaigns, based on more traditional efforts, so far behind that after their loss, Romney’s staff were left exclaiming that Obama’s campaign showed voters that the Romney campaign “did not even know existed.” In 2014, Obama’s pre-election campaign staff said at a Personal Democracy Forum gathering that in key states, they were able to “go deep into Republican territory” to individually target voters they had modeled as likely Democrats, in otherwise Republican suburbs, breaking down the barrier of “geographic perimeter” in voter targeting. The advantages of stronger, better modeling—a costly endeavor that depends on the ability to purchase and handle large amounts of data—are difficult to underestimate.

Finally, big data modeling can predict behaviors in subtle ways and be more effectively oriented toward behavior change. For example, for years, the holy grail of targeting for marketing professionals has been pregnancy and childbirth, as it is a period of major changes for families, resulting in new consumer habits that can last for decades. Previously, retailers could examine obvious steps such as creating a baby registry. However, by that time, the information is often already public to other marketing professionals and the target customer is already pregnant and has already established consumption patterns. However, by combining rich data with predictive models, retail giant Target is not only able to detect likely pregnancy very early, in the first or second trimester, but can also estimate the due date “within a small time window” so that it can send coupons and advertisements timed to the stages of pregnancy and child-rearing. In a striking example, Duhigg (2012) recounts the story of an angry father who enters a Target, demanding to see the manager to ask why his teenage daughter was being sent advertisements for maternity clothes, nursery furniture and baby paraphernalia. The manager, as reported, offered a thousand apologies, only to receive the father’s own apology, who when he returned home to speak with his daughter, she told him that she was indeed pregnant. Data modeling led to events that a parent did not know about his own child living under his own roof.

- Behavioral science

These predictive analyses would not be so valuable without the corresponding development of behavioral science models regarding how people are persuaded, influenced, and motivated to take specific actions. The development of deeper models of human behavior is crucial for transforming the ability to examine, model, and test big data into tools for changing policy behavior.

The founder of public relations himself, Edward Bernays, had argued that people were fundamentally irrational. However, the rational and “practical” aspects of human behavior have long been emphasized in the dominant academic literature, especially in fields such as economics and political science. While Habermas’s (1989) ideal of the public sphere envisioned status-free actors engaging in rational discussions based on shared values, political professionals have long recognized that the model of the “rational voter” did not match their real-world experience. Nevertheless, until recently, there had been relatively little systematic analysis of the “hooks” for guiding “irrationality” toward desired outcomes—the tools required for the instrumental and rational manipulation of human irrationality had not yet been developed.

All this changed thanks to research emphasizing the non-rational aspects of human behavior and efforts to measure and test this behavioral modification within political contexts. As behavioral analysis became more sophisticated, for the first time in modern political history, some researchers from the behavioral sciences moved into practical politics, starting with the Obama campaign in 2008. Consequently, as Issenberg (2012) noted, there was a significant shift from “narratives about subsidies” and the structured conclusions produced by experts to an operational struggle focused on changing the behavior of individual voters, critically supported by insights from behavioral scientists.

It wasn’t that behavioral science could overcome structural obstacles of a campaign such as poor economic policy or a deeply entrenched candidate. Increasingly, however, elections are decided on the margin, partly due to pre-existing polarization—a winner-take-all system, in the case of the United States—but also due to low turnout. Under these conditions, the operational ability to locate and persuade exactly the right number of individual voters becomes ever more important. In such an environment, small differences in analytical capability can be the push that reveals the winner. For example, behavioral political scientists working on political campaigns found that “plain white envelopes” work better than glossy letters in terms of message credibility. As a result, they were increasingly used by Obama’s campaign. Consequently, the fusion of empirical behavioral science with the “psychographic” profiles, derived from computational modeling of big data, as discussed earlier, can create a significant advantage.

The combination of psychographic elements with individual profiles in a privatized (i.e., non-public) communication environment can transform political campaigns. For example, campaigns have often resorted to fear (or other tactics that appeal to the irrational), such as the infamous “Daisy” advertisement and the nuclear war during the 1964 U.S. presidential campaign. However, research shows that when afraid, only some people tend to become more conservative and vote for more conservative candidates. Until now, however, campaigns had to target the entire population, or at least a significant portion simultaneously, with the same message. In contrast, by modeling individual psychologies through computational methods applied to big data, a political campaign hoping to gather votes for a conservative candidate can reasonably (and relatively easily) identify voters who would be more likely to react to fear by voting conservatively and target them individually, with “fear” tactics designed for their personal weaknesses and vulnerabilities, while bypassing individuals for whom invoking fear would not have the desired effect or even the opposite of the desired effect, communicating with them in an invisible way to the broader public, say through Facebook ads.

- Experimental science in real-time environments

The online world has opened the doors to cheap, large-scale, and real-time testing of the effectiveness of persuasion and political communication; a significant innovation for political campaigns. Many campaigns in the past were guided by “indirect knowledge,” “instinctive sense,” and respect for traditional expertise. Empirical discussions about politics would focus, at most, on opinion polls where there was an astonishingly small number of trials or experiments in political campaigns.

There are many reasons for the limited testing, including the fact that political campaigns are essentially businesses—and the consultants who live off them, relying on their “gut instinct,” were never “keen” on experiments that could challenge their strategies and harm their credibility. But most importantly, field experiments are expensive and time-consuming, and money and time are the resources that political campaigns already prioritize the most.

Despite these obstacles, some experiments were conducted. However, their results were often published too late for the elections in question. Field experiments conducted in 2001 that showed face-to-face ” canvassing” was more effective for participation were published three years later. These experiments increased awareness that many methods that campaigns traditionally spent money on (for example, mail services or phone calls) were not very effective. The cultural shift toward measurement came into full application with Obama’s campaigns in 2008 and 2012, which were notable for their “data-driven culture.” Campaign director Jim Messina already declared as early as 2011 that Obama’s 2012 campaign was going to be “driven by metrics.” A culture of experimentation was encouraged and embraced.

This change, however, was not simply a change in perspective, but also a change in technical infrastructure. The rise of digital platforms allowed for the integration of real-time experimentation into the very delivery of the political message itself. A/B testing, as it is often called, involves creating multiple versions of an image or message that are delivered separately to randomly selected control groups. The results are measured in real time and quickly integrated into the delivery, as the “winning” message becomes “the” message. Methodologically, of course, this is traditional experimental science, but it has become possible because campaigns are now partly conducted through a medium that allows for these experimental capabilities: cheap message delivery, immediate measurement, the ability to randomize recipients, and rapid feedback of results, which can then be applied to the next round. Campaign officials involved in such “measurement-driven” campaigns report that their “gut instinct” has often been proven wrong by the experiments.

Obama’s campaign had incorporated experiments into its methods as early as 2007. For example, in December 2007, when Obama’s campaign was still in its early stages, the campaign created 24 different combinations of buttons and multimedia for its homepage. Each variation was observed by 13,000 people—an incredibly large number for conducting a field experiment by traditional standards, but a relatively easy and inexpensive effort in the digital age. In the end, the winning combination (which showed a photograph of his family and children) had a 40% higher “sign-up rate”—translating this into the total number of people who signed up, the impact could be as high as 2,888,000 additional people. Considering that the average contribution was $21 and that 10 percent of the people who signed up volunteered, the difference would amount to an additional $60 million and 288,000 more volunteers, all achieved through a cheap, large-scale, and direct experiment. Through such experimentation, Obama’s campaign primarily led to the presentation of his family in most of the pre-election material.

Such an on-site, large-scale and complex randomized experiment was traditionally rare in the social sciences, let alone in political campaigns, due to cost, effort and ethical criteria. To take into account the implications of such large-scale online experiments, see the recent outrage over the Facebook and Cornell emotional contagion experiment, in which nearly 700,000 Facebook users’ news feeds were manipulated to determine whether those who see more “sad” posts would publish more “sad” posts—and similarly for “happy” posts. The increasing digitization of political campaigns as well as the political actions of ordinary people provides a means through which political campaigns can now conduct such experiments easily and effectively.

- The power of platforms and algorithmic governance

A large volume of political discourse appears in the “fourth power,” which consists of blogs, websites and social media platforms, many of which are private companies. These platforms operate through algorithms, the specifics of which are largely opaque to individuals outside the small number of technical professionals within the company, regarding content display, data sharing and many other features of political consequence.

These proprietary algorithms determine content visibility and can be changed at will, with enormous consequences for political discourse. For example, Twitter, an emerging platform that plays a significant role in information exchange between politicians, journalists, and citizens, selects and highlights 10 “trending topics” per region, which then gain exposure as they are advertised directly on the platform. However, the algorithm that selects topics is proprietary, leading political actors to wonder whether they were censored, while others try to “game” it through reverse engineering. Similarly, nonprofit organizations that relied on Facebook to reach their audience were caught off guard in 2013–2014. Facebook changed its algorithms, meaning that fewer and fewer people who had liked their pages were seeing their updates, reducing visibility from 20% in 2012 to 1% to 2%, introducing a new “pay-to-play” model that required payment to promote posts.

The impacts of opaque algorithms and pay-to-play are multiple: first, groups without money to promote their content will be hidden from the audience or will face changes in their reach that are beyond their ability to control. Second, given that digital platforms can deliver messages individually – each Facebook user could see a different message tailored to them, in contrast to a television advertisement that necessarily goes out to a large audience – the opacity of algorithms and the private control of platforms changes the audience’s ability to understand what is ostensibly part of the public sphere, but now in a privatized/personalized manner.

These platforms also possess the most valuable big data treasures that political campaigns desire most. Campaigns could access this data through favorable policies for platforms that provide them access. For example, mobile apps such as those of the Romney and Obama campaigns can obtain information about the user as well as information about users who are friends of the initial individual who accepts a campaign app, which is a bypass of privacy issues. These private platforms can facilitate or hinder political campaigns in approaching this user information or may decide to package and sell data to campaigns in ways that differentially enhance campaigns, thus benefiting some over others.

Moreover, a “biased” platform could decide to use a private storage space for big data in order to model voters and target the voters of a candidate who favor the financial or other interests of the platform’s owners. For example, a study published in Nature found that “go vote” messages promoted to Facebook users through their contacts (thanks to a voting encouragement app developed by Facebook) resulted in a statistically significant increase in voter turnout, unlike a similar “go vote” message that appeared randomly. A platform that wanted to manipulate election results could, for example, “model” voters who would be more likely to support a candidate it itself would prefer and then promote a targeted “political” message to the majority of such voters, so that most recipients would be the desired “targets,” while also including some from other groups to make the targeting less obvious. Such a platform could influence the conduct of elections without ever asking voters whom they prefer (collecting this information through modeling, something research shows is quite feasible) and without openly supporting any candidate. Such a program would be easy to implement, practically undetectable by observers (since each individual sees only a portion of the social media feed and no one sees the entirety of messages across the entire platform, except the platform owners), easily disputable (since the algorithms involved in things like Facebook’s news feed are proprietary and well-guarded secrets) and practically impossible to prove.

A similar technique could also be possible for search results. Ordinary users often do not visit pages that are not highlighted on the first page of Google’s search results, and researchers have already found that a slight change in ranking could influence elections, without alerting voters. Indeed, based on randomized experiments, Epstein and Robertson (2013) concluded that “with sufficient study, optimal ranking strategies could be developed that would change voters’ preferences while rendering the ranking manipulations undetectable.” By maintaining valuable big data repositories and controlling the algorithms that determine the visibility, sharing, and flow of political information, major companies and social platforms of the Internet have emerged as incomprehensible, but significant, “power intermediaries” of “internet politics.”

- https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/ftc_gov/pdf/1.%20Complaint.pdf ↩︎

- Why we’re concerned about profiling and micro-targeting in elections – 30/4/2020 – privacyinternational.org ↩︎

- Engineering the public: Big data, surveillance and computational politics – https://firstmonday.org/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/4901 ↩︎

- There is also a related reference in Metadata: Data under the microscope, Cyborg #19 ↩︎

- Related reference to Semantic technology: the reconfiguration of meaning, Cyborg #21 ↩︎