Dark years are coming. Not because “our future has much drought,” but because the drought now spreads to the past too – which is the source of every future. Freedom is not simply lost (after all, it never truly existed); the very idea of it is lost, that is, its absence – the sparkle of it fades from the eyes of the slaves. The happiness of the animal dawns. Perhaps the daily bread will abound. But the bread and wine that once nourished the community of humans will be lacking.

G. Lykiardopoulos

As conscientious citizens of a certain Western democracy, your ecological conscience compels you to make a small change to your television program and pause for a moment from consuming garbage in order to enjoy the latest documentary that your subscription platform has to offer you regarding some endangered species in an African park and the efforts to save them; an extinction for which it is implied that climate change is to blame. Your guide in this ecological adventure is some white Western biologist who, with his khakis, cargo pants, dirty boots, his long braid, and unshaven face, resembles a reincarnation of Indiana Jones, although his visible excess weight somewhat spoils this image at the moment.

Small digression: the hopeful Indiana Jones has as his guide a tall, lean African native from the region, wearing only an Adam’s fig leaf and bearing a permanent, disarming smile on his face. Only the camera seems to ignore him, allowing him to appear only incidentally and fleetingly in certain shots. It clearly favors the well-groomed westerner, showing him moving among lions, elephants, and rhinoceroses like a savanna hunter. With unmatched courage, like another ecological Rambo, he tranquilizes animals left and right and equips them with tracking devices for easier recording and analysis of their movements. And as if this emotional display of self-sacrifice by western crocodile-hunters and their eagerness to teach the natives how to manage the environment in which they have lived for thousands of years weren’t enough, the episode suddenly takes a new turn to reach a dramatic climax. The radio informs them that poachers have been spotted on the other side of the park! The camera’s shot begins to shake as the team runs behind the green-robed figure to board the helicopter together. A few high-angle shots sweep across the savanna, with anxious zooms following one after another. There! There! The helicopter alerts the monstrous four-legged creatures moving below, and they accelerate through the dust to surround the dishonorable poachers. They immobilize them, waiting for the helicopter to land. The camera returns to the ground and approaches trembling toward the center of the circle, where the despicable violators of Mother Earth stoically await with their heads bowed. The biologist informs the local eco-police, and you can now withdraw, relieved and hopeful that your children will someday live in a world where rhinoceroses still roam. However, just before sleep takes you, behind your heavy eyelids, a question may form. Why had the local guide stopped smiling when, for a moment, he was caught in a shot next to his captured compatriots? You have no strength for such questions at night, though. It’s already late, and who can handle the morning wake-up call? “Goodnight, my love.”

The power of propaganda surrounding the so-called environmental issues has now reached such a level of gravity that it seems to absorb any attempt at criticism against the so-called green transition. Once again, science speaks with objective data, and the solutions appear unequivocal. Black or white, choose and take your pick. Like some Tolkien tale, on one side are the “good guys” of the cause, the saviors of humanity and the entire Earth; on the other side are the malicious werewolves of nature, the incorrigibly selfish who insist on ignoring scientists’ warnings. Should there not be nature reserves and ecological parks? Should we let rhinoceroses disappear? Why not install wind turbines on every mountain peak and solar panels in every field? Should we continue burning fossil fuels and eventually boil in a greenhouse? Isn’t it high time we got rid of internal combustion engines? Or would you rather prefer to sink beneath the sea as the ice melts?

Regardless of the validity of relevant scientific analyses regarding human-induced environmental destruction, the Manichean way in which such dilemmas are posed should, by itself, raise suspicions about their targeting and the sincerity of intentions on the part of those who undertake to formulate them on a contractual basis. Because it is precisely a type of questionnaire that attempts to confine thought within artificial deadlocks and lead it toward preordained “solutions.” If, furthermore, one takes into account the fervor with which the adjective “green,” in all its variations, is mobilized on every occasion and for every use by states, companies, and billionaires, then simple suspicions should be transformed into an urgent need to critically analyze all this “ecological” (but at its core revelatory) rhetoric regarding its intentions. When “green” has been transformed into an ideological floating signifier that can be attached as deemed appropriate (that is, according to the demands of states and companies) to any signified, it (should) become clear that it can have little relation to real ecological concerns and that it rather functions as a weapon within the framework of harsh geopolitical and class competitions.

There is initially a justified reluctance to view ecology through the prism of such competitions and to place it on the opposite side, as a hostile ideology (in the Marxist sense of the term). A reluctance that becomes understandable to the extent that ecology managed to draw a large piece of its vital force from a competitive environment that once had a clearly anti-capitalist and anti-systemic sign. The labor, feminist, and ecological denials marched side by side for a long time, sometimes demonstrating a high degree of osmosis, despite occasional friction. However, the inability to synthesize them into something more robust might have been one of the factors that led to the collapse of all three. Such an inability was not merely theoretical and abstract. It was cultivated from above in a way. The rhetoric about the disappearance of the working class in post-industrial societies, identity politics as a mutation of feminism, and so-called sustainable development (which is a contradiction in terms) as a defunct form of ecology played a crucial role in the attempt to tame the reactions of that time or even to creatively integrate them as pillars of the established ideology. In any case, it should be taken for granted that what is presented today as the “ecological movement,” urging us to get rid of plastic straws and get used to electricity coupons, has traveled a very long distance from the form it had in the 1970s. Insisting on considering it an ally of the enslaved populations around the planet would not simply be political naivety, but a deadly danger, bordering on suicide.1

To better understand this mutation of ecology, a more macroscopic view is also needed. What then were the beginnings of ecology as a way of thinking about the relationships of humans with their environment and as a science? Concerns about the impact of human activities on the environment, viewed through the lens of the scarcity of goods and lack of resources, had been expressed from time to time in various historical periods and in the most diverse societies, from Ancient Greece and Rome to India2. Already ancient Athens had faced the problem of timber shortage due to excessive deforestation for the purposes of building new ships. However, nothing had ever been systematically formulated that resembled an ecological perception of nature as a holistic system of which humans constitute a part, with whatever limitations this (should) entail for the intensity of exploitation of this nature.

Some early perceptions in such a direction (even regarding climate change) would finally emerge in Europe only in the 17th century, and with clearer outlines and in a more systematic form from the second half of the 18th century. This second and somewhat more mature “ecological” wave (here the term “ecological” is used slightly anachronistically and retroactively since it had not yet been invented) had deep roots in the general intellectual climate of the European Enlightenment and in the rising popularity of physiocratic theories that gradually displaced the more traditional religious worldview of medieval Europe. However, as was typical for that era, scientific curiosity (among other things about the boundaries of nature) was not purely theoretical and contemplative. Especially for the French physiocrats, understanding the mechanisms and processes of nature was accompanied by demands for social transformation, for some of them even in an anti-capitalist direction. By the end of the 18th century, British and French botanists would explicitly express some initial fears about the possibility of species extinction as a result of human interventions in nature, while some early experiments in forest and water protection would take place on the island of Mauritius. In 1852, doctors in the service of the (British) East India Company published a study (Report of a Committee Appointed by the British Association to Consider the Probable Effects in an Economic and Physical Point of View of the Destruction of Tropical Forests) in which they warned in the strongest terms about potential catastrophic consequences if forest protection measures were not taken.

This brief overview of the origins of ecological thought may create the impression that ecology is tied to some sort of navel cord with anticapitalist agendas and that it developed in radical opposition to the rampant industrialization that would be set in motion by the first phase of capitalist expansion. Although correct in some respects, such an image remains seriously biased regarding the historical trajectory of ecology. It is accurate in that ecological concerns essentially developed in synchrony and kept pace with the waves of industrialization and the spasms of capitalist development. In some cases, they even came into opposition with the capitalist logic of economic growth and the ruthless exploitation of nature, sometimes drawing (as, for example, in the case of Thoreau) from the romantic tradition. Yet not in all cases. Perhaps not even in most. Running parallel to this “romantic” current flowed another, distinctly more mechanistic, technocratic, and to a far greater degree compatible with the economic demands and perceptions of the market economy.

“By the term Economy of Nature we mean the all-wise stance of the Creator in relation to all things of nature, which ensures that all things are done to serve general purposes through a mutual interdependence.”

“…all living beings must continuously be used in such a way as to produce new individuals; all things of nature must contribute and assist in the preservation of every species; finally, the death and destruction of one must constantly be in the service of the restoration of another.”

“…in cases where the population increases excessively, harmony and the ability to meet the needs of life diminish, while envy and malice towards neighbors abound. We thus have a war of all against all!”

The above excerpts date from the 18th century and belong to Linnaeus, the well-known founder of modern biology3. Although terms such as “ecology” (proposed in 1869 by Ernst Haeckel) and “ecosystem” (introduced in 1935 by Arthur Tansley) had not yet been established, Linnaeus seems to have already grasped a more holistic idea of nature and living organisms, which live and reproduce in continuous interaction with one another within an environment that possesses only finite resources to meet their vital needs. Even from these brief excerpts, it is evident, however, that Linnaeus’s perceptions had little to do with any kind of “romanticism.” On the contrary, he understood the processes of generation and decay of living organisms in a way analogous to the circulation of money and goods within a market economy—it is, of course, not coincidental that the term “economy of nature” was employed. In fact, the concluding phrase of the excerpt literally replicates the Hobbesian perception of human societies, which in turn was naturally in direct correlation with the establishment and expansion of the new economic system4.

At the same time, an obsession with the “problem of overpopulation” was already quite widespread from the second half of the 18th century, culminating naturally with the well-known work of Malthus in 1798, An Essay on the Principle of Population. Darwin’s ideas during the 19th century would add yet another piece to the puzzle of this grim version of ecology, insisting on the unyielding nature of competition as a foundational principle of biological evolution—adding, however, in contrast to Linnaeus, that species are not fixed and immutable, but that they continually disappear in order to give rise to new ones. While both ecological currents shared certain common concerns regarding the fate of nature and humanity within it, they approached these from radically different perspectives. The “romantic” tendency leaned toward a more cooperative and dialogical understanding of the relationships between humans and nature, whereas the “economistic” approach reified biological competition to arrive at a more managerial perception and more technical solutions regarding the problem of environmental destruction. This polarization between the “romantic” and “economistic” spirit of ecology would mark its further trajectory during the first half of the 20th century, with the latter gaining the upper hand from the 1940s onward. It was then that the vocabulary of ecology became filled with new terms, such as “productivity,” “efficiency,” “flows of goods and services,” eventually coming to openly speak about “green growth.”

None of the two aforementioned currents should therefore be considered more “true,” more “ecological,” or more “rational” than the other. Both are equally “scientific” or “rational” (in terms of purpose, to recall Weber’s distinction between goal-oriented rationality and value-oriented rationality) – if the goal is to exploit natural resources for the sake of economic development without completely exhausting those resources, it is entirely rational to speak of environmentally friendly technologies and green growth. What gave the environmental movement its momentum in the decades following World War II was not some new scientific data, nor that it proved more rational in the field of technology, but rather that it became directly connected to the broader movements of the time, just as its distant predecessors had once done, by proposing an alternative value system.

For those who follow even superficially the economic and political developments beyond the boundaries of the Greek provinces (and are not confined to protests over wiretaps and demands for early elections), it should be clear on which side the pendulum of ecology currently lies. The Greens (with Germany’s as pioneers) have not merely become institutionalized, but have turned into the spearhead of an ongoing capitalist restructuring. The fresh green of meadows has begun to take on the hue of the dark olive-green of mold and the new totalitarianism. The question that naturally arises at this point concerns the causes and aims of this mutation. Why is this slippage of “ecology” toward a hybrid of neodarwinism and technocracy now observed, and what horizons does it open – or rather, closes – for those who are, or will soon find themselves, in a position of powerlessness?

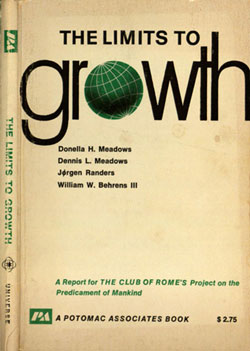

To grasp from a certain starting point the thread of these ideological rearrangements, it is perhaps worth looking at the time when states and corporations began their counterattack in the green field. Speaking of the modern era, this time point could ideologically be placed in 1968, the year the well-known Rome Club was founded, a “non-profit” organization led by figures from the business sector and the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). Its supposed purpose was to study from a holistic perspective the complex problems that humanity would face from that point onward. A result of these efforts was the famous report “The Limits of Growth,” published in 1972, which raised concerns about the sustainability of a model of unchecked growth and overpopulation (him again!) given finite resources. At first glance, the goals of this club may seem noble. However, it would be a serious political mistake to accept unquestioningly such moves as the result of a crisis of sincerity and self-criticism on the part of states. If these efforts are placed within the broader political and geopolitical climate of the time, a somewhat different picture emerges.

The major energy event of that era, which shook the foundations of Western capitalist structures, was of course the 1973 oil crisis, when OPEC countries decided to impose an embargo on Western countries supporting the aggressiveness of the Israeli state. Such a fact alone could be seen simply as another move on the geopolitical chessboard. However, it was not an isolated incident. By the end of the 1960s, the U.S. had already reached a deadlock in terms of domestic oil production, which simply could not meet demand. Their share of global oil production had fallen to 16% by the time the oil crisis erupted. Therefore, the very year the Rome Club was founded, there was already widespread concern about the sustainability of the Western energy model, both as a capitalist and a geopolitical model, regardless of any ecological concerns.

Based on this data, it would not be an exaggeration to assume that around the years 1970, an effort began to more strictly control energy reserves in order to ensure as smooth a reproduction as possible of an economic system heading towards the 3rd industrial revolution. Elements of ecological rhetoric were able to readily provide an ideological cover for such an endeavor, especially since the economic mainstream had autonomously developed a compatible vocabulary around concepts such as “productivity,” “competition,” “reproduction cycles,” etc. What is important to understand here is that this was not (neither then nor now) an attempt for a complete elimination of fossil fuels—which, in any case, appears to be anywhere from difficult to impossible from a technical standpoint and given the demands of the existing energy model. Nor was it an attempt at overproduction that would lead to an oil surplus.

The key point is the ability to precisely control this production, creating oversupply or scarcity whenever and wherever this is necessary. It is obvious that imposing rules regarding pollutant emissions (rules that are largely shaped by the already developed Western countries) automatically translates into rules governing the margins of production, circulation, and use of fossil fuels. Regardless of whatever contribution these fuels make to climate change (a contribution that is heavily disputed), the fact remains that whoever has the ability to set and enforce these rules will be in a position to control the manner and extent of their use.

As much as it may not be obvious at first glance, central importance in this attempt to control energy flows also has the position of the dollar as the global reserve currency. The dollar may have been detached from gold in the 1970s, but it has been, albeit somewhat informally, tied to oil. Since oil transactions are conducted in dollars (something that has been changing in recent years and is likely an irreversible change), oil has become a de facto regulator of the dollar’s value. On one hand, the demand for dollars provides a kind of cheap loans to the American state. On the other hand, an excessive supply of oil would inevitably lead to the depreciation of the dollar. For the maintenance of American – dollar hegemony, it is therefore of crucial importance the extent to which the control of the production and circulation of fossil fuels is possible. In other words, the control of countries that possess such reserves, such as those of Central Asia and Russia, especially after the collapse of the Soviet Union5.

In a second phase, this control necessarily extends to countries that need energy resources for their own development, with China here being the archetypal example. For countries that have gone through a phase of significant deindustrialization (in terms of the 2nd industrial revolution), developing based on the steroids of financial and gambling products (the beginning of whose evolution is again placed in the 1970s), competitors like China, who persist in more “traditional” forms of development, appear as a deadly threat. The imposition of “green” technologies globally would automatically place obstacles to such “irresponsible” development, allowing the pioneers of “sustainable development” to regain the advantage.

Beyond any reasons of geopolitical competition, however, it is not difficult to discern reasons of internal discipline behind the push for “environmentally friendly” technologies. The holy grail of the 4th industrial revolution goes by the name “universal interconnection of everything.” Something that obviously presupposes an unprecedented spread of electrical and electronic devices. To impose this model change, a trick of intellectual sleight of hand is employed. Whatever is electric(al) is presented as clean, odorless and noiseless, which ought to displace the dirt and grime of the internal combustion engine6. The change in consumption and social reproduction model thus appears in a magical way as an inevitable energy model change, concealing the fact that both the required amounts of electrical power and the production of the devices themselves may leave an even heavier ecological footprint compared to more traditional forms of energy7.

However, such intellectual subtleties find no room for expression when the goal is the largely violent restructuring of entire societies according to the standards of universal connectivity. Because, apart from the economic factors that provide momentum for such a large-scale transition, there also lurks the need to manage the populations on whose heads such experiments are about to be tested. With Western economies having been at their limits for decades, continuously attempting leaps toward a financial future in hopes of postponing serious upheavals for as long as possible, the need to discipline their internal populations becomes increasingly urgent. The key tool in this direction will be precisely this much-touted universal connectivity, which is advertised as the royal road to a green future of ecological cities. The surveillance capabilities opened up regarding consumption (e.g., through digital currencies) and social behavior in general (e.g., through social networks) reach an unprecedented depth that will not remain untapped and goes far beyond some kind of “neo-feudalism” (a term often used by certain anti-systemic circles). The oil wells may perhaps run dry someday in the future. But the wells of personal data have only just opened, and the need to exploit them must be cloaked in some ideological pretext that will justify this exploitation, naturally for the sake of saving the planet.

Yet perhaps the darkest of all developments under the guise of the green transition has less to do with the cycles of production, consumption, and social reproduction. The subordination of ever-widening spheres of production and the social to capital’s dictates has been a constant pattern throughout capitalist history, serving as a springboard for overcoming crises—150 years ago, who could have imagined that entertainment itself would be industrially produced and consumed for money? What now appears to be happening is that, under the pretext of the green transition, the very processes of natural (animal and plant) reproduction are being organically integrated into commodity circulation. This is not an entirely new development. Attempts to enclose natural resources through the creation of parks and “pristine” areas have occurred in the past, aiming to ensure that these resources would not be depleted or fall into the “wrong” hands. However, the universality of the new enclosures constitutes a kind of fulfillment of the dreams of that old economic current within ecology. To the extent that opportunities for extracting surplus value through more traditional means have for now been exhausted, nature itself is transformed, in its entirety, into a new field of exploitation—even down to the cellular level8.

Man becomes increasingly responsible for the conservation of nature, yet nature itself is assigned no autonomous value. On the contrary, it is called to be preserved only insofar as it is integrated within the purposes of economic development. Thus, nature acquires a dual character. On one hand, it is conceived as something utterly distinct, as the absolutely external which one can enjoy only occasionally and with the utmost precautions—this perception is precisely what the creation of special parks promotes, by drawing a deep dividing line between what should be considered “natural” and what is deemed “human.” On the other hand, as something external, nature is also transformed into an object, into something requiring continuous interventions on the part of humans, either simply to survive as such, or to serve human (read capitalist) purposes. A park is not merely something that is untouched—an idea which, in any case, is deeply paranoid. At the same time, it can also be a warehouse of resources whose exploitation may at some point become imperative. Or even a genetic repository containing biological wealth available for study and utilization. In this way, nature becomes external with respect to individuals, but internal with respect to the economic system which those very individuals have set in motion. In other words, this constitutes the definition of alienation. Alienation even from one’s own body and its vital processes.

Whoever expects a bright future from the green transition will be utterly disappointed – unless they belong to those who anticipate some benefits from it. If the environmental movement once thought it could perpetuate its existence and value by remaining relatively isolated and without touching broader issues, it is now time to learn a harsh lesson. As long as it follows such logic, its only chance of survival is to be fully absorbed by the very mechanisms it once opposed, transforming into a vampire that keeps nature alive only to the extent necessary to drain its forces. And thus it will bring about its own demise, once nature has been reduced to nothing more than a moment of technology.

Separatrix

- This does not mean, of course, that as a reaction to today’s degeneration of ecology, one should throw the entire ecological movement into the dustbin of history as inherently reactionary. We make this observation because such cases of reflexive rejection of any ecological concern have fallen under our perception, even from (former or current, perhaps they themselves do not know) Marxists, for whom there is no issue with fossil fuels or even nuclear energy, and who believe that human prosperity necessarily relies on the existence and exploitation of large energy reserves. See, for example, the British, formerly Marxist and now (rather) conservative magazine spiked. ↩︎

- See Green Imperialism: Colonial Expansion, Tropical Island Edens and the Origins of Environmentalism, 1600-1860, R. Grove, Cambridge University Press. ↩︎

- They were fished from A History of the Ecological Sciences, Part 23: Linnaeus and the Economy of Nature, F. Egerton, The Bulletin of the Ecological Society of America, 2007. See also Nature’s Economy: A History of Ecological Ideas, D. Worster, Cambridge University Press. ↩︎

- See Atomism and Property. The political theory of early liberalism from Hobbes to Locke. C.B. Macpherson, ed. Gnose, trans. Eleni Kasimi. ↩︎

- For more details, see the ideological management of climate change, Cyborg, vol. 16. ↩︎

- Interesting “anecdote”: About a century ago, when the 2nd industrial revolution was at its peak and there was a backlash against accepting internal combustion engines, a key reason why electric cars (which were already circulating and could have been even more efficient than those with internal combustion engines) were rejected was precisely because they were odorless and noiseless. For this reason, they were also considered more effeminate, in contrast to those powered by internal combustion engines, which resembled more like “wild beasts” and their driver as a kind of rider who had to tame the beast. ↩︎

- See climate change and 4th industrial revolution, Cyborg, vol.17. ↩︎

- See the related articles by Whitney Webb, Wall Street’s Takeover of Nature Advances with Launch of New Asset Class and UN-Backed Banker Alliance Announces “Green” Plan to Transform the Global Financial System. ↩︎