They can1 write poems and stories on their own, they can converse with a person with impressive naturalness, they have a particular knack for writing college assignments on behalf of students who prefer (probably rightly) to spend their time otherwise, they have talent in programming and prove it by writing malware; lately there have been thoughts to use them during a trial to provide real-time legal advice. No, it’s not about anything children – miracles that grew up and were educated in secret, underground laboratories and now came out into the world. All these are some of the achievements of ChatGPT, GPT-3 and LaMDA, some of the most well-known artificial intelligence systems for processing (and producing) natural language that recently became publicly available (at least the first two, although registration is required), thus giving rise to another round of discussions about whether we are close to creating “thinking machines”.

It is almost certain that these systems, which belong to the category of so-called large language models, could successfully pass the infamous Turing test, at least provided that the dialogue would be relatively brief. One issue that arises here concerns how suitable the Turing test actually is for judging the “intelligence” of a system. This is the most “behavioral” aspect of the matter; we deal with how something behaves, regardless of how it arrives at that behavior. Another issue, however, concerns precisely this “how,” the internal operation of these language models that allows them to conduct such realistic dialogues. Beyond any prestige that such knowledge of the “inner world” of these models may have, it certainly helps in demystifying them. Offering explanations such as “these are models based on deep neural networks that use transformers” probably doesn’t help much; on the contrary, it might intensify the sense of mystery. To better understand their internal structure, one first needs to take a few steps backward.

Suppose, then, that we are called upon to solve the following mathematical problem (don’t panic, those of you who aren’t particularly familiar with mathematics; only addition and multiplication are required to understand what follows). We are given the equation w1 × a1 + w2 × a2 = b, where a1, a2, and b are variables, with a1 and a2 taking only two values: either 0 or 1. The goal is to find suitable values for the parameters w1 and w2 such that whenever both a1 and a2 take the value 1, the value of b exceeds a certain given threshold, say 10. Otherwise, if either a1 or a2 (or both) have the value 0, then the value of b should be below 10. For better and more intuitive understanding, the problem can be represented in table form as follows:

| a1 | a2 | b |

| 1 | 1 | >10 |

| 1 | 0 | <10 |

| 0 | 1 | <10 |

| 0 | 0 | <10 |

With a few trials, it is easy to find a solution to this problem. For example, we could choose the following as a solution: w1 = 5 and w2 = 6. Therefore, our initial equation becomes 5 x a1 + 6 x a2 = b. By testing all combinations for a1 and a2, it is possible to confirm that this is indeed a solution to our problem. If, for example, we set a1 = 1 and a2 = 1, then we obtain the result 5 x 1 + 6 x 1 = 5+6 = 11, as it should be. Likewise, if a1 = 1 and a2 = 0, then it follows that b = 5 x 1 + 6 x 0 = 5. For a1 = 0 and a2 = 1, it follows that b = 6. Finally, for a1 = 0, a2 = 0, it follows that b = 0. There are, of course, other solutions to the problem (e.g., w1=8 and w2=7), however the important thing is that we managed to find at least one.

If you were able to follow the above reasoning and solve the initial problem, then congratulations! You have just used a neural network to simulate the AND operator of Boolean algebra, and you can claim that you built a small brain capable of logical reasoning. Of course, if someone were to present the problem using such heavy and obscure terminology, it would be only natural that no “layperson” would be able to not only solve it but even understand what it’s about. A common tactic, in fact, in the discourse surrounding artificial intelligence—which is now being produced at an inflationary pace—is precisely the use of an incomprehensible language, inaccessible to the uninitiated, which is often presented almost as evidence of both the importance of the problem (“let’s build intelligent machines”) and the proposed solutions (“let’s make them resemble the brain”). In reality, however, although the technical and mathematical details may indeed be extremely complex, the basic ideas certainly do not need to be shrouded in the dark fog of mystery (in contrast, for example, to quantum mechanics and relativity, which are indeed difficult to grasp not only mathematically but even conceptually).

How then can an equation of the form w1 x a1 + w2 x a2 = b correspond to a neural network that can even perform logical reasoning operations? First, it must be understood what Boolean algebra exactly is. Although not as well-known to the general public as other great mathematicians, Boole (1815 – 1864) rightfully holds a special place among specialists in the history of mathematics. His theory is distinguished neither for its complexity nor for the use of complicated and intimidating mathematical tools. His achievement is considered important mainly at a conceptual level. What Boole managed to do, therefore, was to grasp the idea that classical, propositional logic (the one already known since Aristotle) can take an algebraic form. In other words, to be formulated in the form of equations which can be solved based on certain basic rules, largely like the formal equations of classical algebra which handle real numbers.

The basic difference compared to Boolean algebra is that in the latter, variables (a, b, etc.) take only two values, either 1 or 0. By convention, 1 corresponds to what in logic is the truth value TRUE, while 0 corresponds to FALSE. Based on this convention, we can use the symbols of operations (e.g., addition and multiplication) to formulate logical propositions in the form of equations.

For example, suppose we have the propositions p, q and r (where p semantically might mean that “Socrates is human” and something similar for q and r) and we want to say that r holds (i.e. is true) only if both p and q hold simultaneously. Such a proposition can be written in Boolean algebra as p x q = r, where here the multiplication symbol is used to denote logical conjunction (AND). Logical disjunction (r holds only if at least one of p and q holds), on the other hand, can be written as p + q = r, where the addition symbol is given a new meaning here. Therefore, if in the proposition p x q = r we set p = 1 and q = 1, then it follows that r = 1. In any other case, it will hold that r = 0. Starting from such basic rules, it is possible to construct logical propositions of great complexity, with multiple combinations of the various operators. Because it precisely succeeded in formalizing logic, Boolean algebra also constituted the first major step toward its mechanization; today all digital circuits are based on it.

From the above, it is rather obvious why the equation w1 x a1 + w2 x a2 = b, with the appropriate weights w1 and w2, corresponds to a Boolean equation. In fact, it corresponds to the operation of logical conjunction. Whenever the variables a1 and a2 both take the value 1, the output (that is, the variable b) takes a value greater than a threshold. In any other case, its value is below this threshold. The 10 in this particular case is completely arbitrary and could have been replaced with any other number. The key point is the general behavior of the equation: exceeding the threshold is interpreted as 1 and any other output as 0.

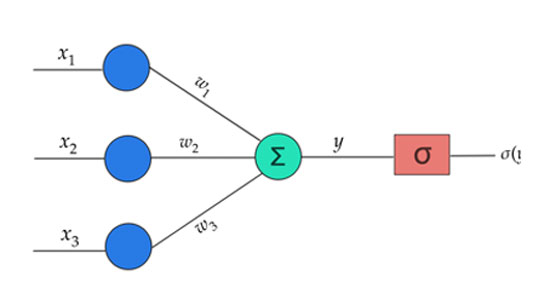

The second issue that needs clarification is how the equation w1 x a1 + w2 x a2 = b can correspond to a neural network. The most basic and simple neural network is the so-called perceptron and consists of a single node – neuron. This receives a series of inputs (a1, a2, etc.) and each of these inputs is accompanied by a weight (w1, w2, etc. respectively). What the node does is multiply each input by its corresponding weight (w1 x a1, w2 x a2, etc.), then add all the individual results of the multiplications (w1 x a1 + w2 x a2 + …) to produce a first output b and finally pass this output through a threshold, as we have already described. By now adjusting the various weights, we can “push” the perceptron towards a desired behavior, e.g., to simulate logical conjunction, logical disjunction or other logical (and non-logical) operations. The adjustment of these weights towards a specific direction is what in the relevant literature is called “training” of the network and of course it is not performed manually (as we simplistically presented above), but with appropriate algorithms.

A basic question that arises at this point has to do with why such a series of mathematical operations (multiplications, addition, threshold) is called a “neuron”. What relationship could it have with the real neurons of the brain?

A different name for the perceptron is also the McCulloch–Pitts neuron, named after the two scientists who proposed it as an idea in 1943. The reason why this particular mathematical structure was characterized as a “neuron” relates to the supposed similarity it presents to real, biological neurons. The first experimental observations regarding the functional behavior of biological neurons had shown that the synapses attached to a neuron transmit electrical pulses to it from the preceding neurons. The neuron receiving these pulses appears to sum up the incoming signals, and if their total strength (which also depends on how strong the synapses are) exceeds a threshold, then it fires in turn. In this way, it transmits a new electrical pulse along its axon to the next neurons, the strength of which, however, always remains constant (some tens of mV), regardless of how many and how strong the signals it received as stimuli. Comparing therefore a biological neuron with the perceptron, some similarities are obvious. The variables a correspond to the stimuli–pulses received by a biological neuron, the weights w correspond to the synapses, and the final threshold operation corresponds to the “cut-off” imposed by a neuron on the amplitude of the pulse it produces if it eventually fires. The perceptron was a first, primitive attempt to model real neurons.

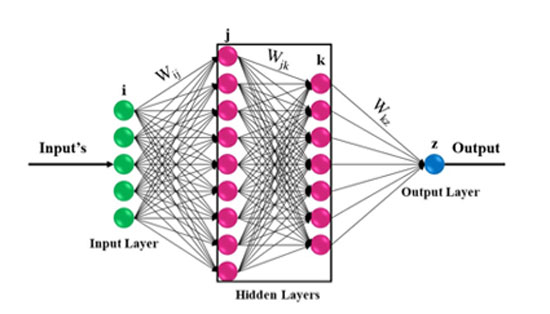

It is of course understood that since 1943, a lot of water has flowed under the bridge of scientific research on the “secrets of the brain.” Perceptrons are now rarely used as realistic simulators of biological neurons. Modern neural models employ a host of differential equations that are considerably more demanding to solve than a few multiplications and an addition. Perceptron-type neurons, in various forms, are still being used, but not for modeling biological brain functions. Strictly speaking, they are not even networks, since they consist of just one node. However, their usefulness lies primarily in the fact that they serve as the basic building blocks for constructing artificial neural networks trained to solve machine learning problems (e.g., recognizing road signs on streets) without any particular commitment to mimicking how the human brain operates on the same problems. As for perceptrons themselves, in their form as individual nodes, it was relatively quickly realized that they have serious limitations (e.g., it was mathematically proven that they cannot solve the XOR logical operation, i.e., exclusive disjunction, where the output must be 1 if and only if exactly one of the inputs is 1 and the other is 0). Such problems were addressed with the introduction of neural networks proper, such as multi-layer perceptrons, which consist of multiple nodes arranged in successive layers, with each layer’s outputs feeding into the next layer’s inputs. It was also crucial that in the 1980s, a “correct” and efficient method was finally discovered for training these networks (i.e., defining the weight values of the connections between nodes). As one might expect, the variations here are countless. How many layers a network will have, how many neurons each layer will contain, whether a neuron will feed into all neurons of the next layer or only some of them, whether certain neurons will be able to skip the immediately next layer and connect to another one deeper down, or even whether they will have backward connections linking to previous or even the same layer—all these constitute just a few of the design choices a modern engineer must make, depending on the problem they need to solve.

To the extent that neural networks constitute statistical models (the more frequently specific patterns they need to learn appear, the more the appropriate weights are reinforced or suppressed), their input must be a series of numbers. Nevertheless, they do not work only with numerical data. For example, they are used extensively to “read” (or even generate) images or audio signals. This is feasible provided that the original signal (image or sound) is first converted into a series of numbers; images are converted into numbers each representing a pixel and its intensity, and sounds accordingly into numbers representing the intensity of the audio signal. Apart from images and sounds, however, they can also handle textual (non-audio) data. Exactly how a sequence of letters is converted into numbers is not as obvious as in the case of audiovisual data, though this does not constitute an insurmountable obstacle. A simple conversion method is to assign each letter of an alphabet to a “vector” of binary values, that is, a sequence of 0s and 1s. The letter ‘a’, for instance, corresponds to the sequence [1 0 0 …] which has a 1 in the first position and 0s in the remaining 25, ‘b’ to [0 1 0 …] and so on. In practice, slightly more complex techniques of correspondence between letters and numbers are used (such as so-called embeddings). In any case, what matters here is that such a correspondence is indeed possible, which in turn means that neural networks can be trained on linguistic data as well.

For what purposes? The simplest case is the use of such models for automatic text correction. A more demanding application is automatic translation between languages. The values for the most impressive example of use so far, however, should rather be attributed to the so-called “large language models”, such as ChatGPT and OpenAI’s GPT-3. These specific models have the ability to automatically generate text either by extending an initial text provided by the user or even by answering questions or generally by responding to user prompts. The reason they have made a big impact is because the texts they produce are almost always distinguished by their absolute syntactic correctness (those who had dealt with the first translation tools of this kind may remember that the translated text often had syntactic irregularities) as well as because they possess a (at least at first glance) semantic coherence, thus giving the impression that they could easily pass the Turing test with their naturalness and “fluency”2.

From a purely technical perspective, what is also impressive about large language models is that their achievements are not due to the use of dictionaries or linguistic (syntactic, grammatical, semantic) rules. No one has programmed them with rules of the type “after the subject follows the verb and finally the object.” Whatever rules they use, they learn indirectly, through the texts on which they have been trained. After their training, these rules have been “encoded” in their weights, although in reality it remains extremely difficult to identify the weights corresponding to this or that rule. This specific ambiguity makes these models somewhat “opaque,” in the sense that there is no possibility to explain their behavior in a human-understandable way. Regardless of such interpretive issues, however, the important thing is that their achievements are based purely on discovering statistical regularities within the texts they have already seen. When a user asks ChatGPT “to write a story in three paragraphs with wizards, dwarves, monsters, and knights,” it responds readily (perhaps even giving original names to the heroes) because it has already consumed corresponding texts, has built up a repertoire of appropriate phrases (along with what usually precedes and follows each phrase), and can recall, paste, and recombine them in various ways. For this process to be successful (i.e., realistic), it obviously requires a huge volume of textual data to train the models and create a sufficient repertoire of standardized phrases. This in turn implies that bulky (in terms of neuron count) language models are required, ones that possess the appropriate “capacity” to store multiple combinations of word sequences in order to combine them and produce a sense of originality. Today’s models have reached the point where they stack hundreds of neuron layers one after the other (hence they are called “deep” networks), with the total number of parameters—weights—reaching several billion.

As Gary Marcus, one of the pioneers in the field of artificial intelligence (and slightly critical of the recent trend to use exclusively neural networks at the expense of other methods), has formulated it, the neural networks behind language models are the “lords of the pastiche”. What they produce is indeed a statistical product, but not exactly random, if by this term one means that even a monkey in front of a typewriter might eventually “write” a poem by Borges. Such a model, in contrast to a monkey randomly pressing keys, will never write a completely unrelated sequence of letters (something like “pslomph, ggfkp oeifmpsa”), without this meaning that it produces text following “thought”. Their output is generated purely statistically, through textual cut-and-paste. The great verisimilitude of their texts is due precisely to their high combinatory ability.

On the other hand, this is also one of their weak points. Since they do not possess any ability to perform reasoning, when they make errors, these are often monstrous and childish; the user asks “what is heavier, a kilo of steel or a kilo of cotton?” and the model confidently answers with “arguments” that of course one kilo of steel is heavier because somewhere within the texts it has consumed, steel is always considered heavier than cotton.

At the same time, for the designers of these networks, it is a serious problem to identify exactly why such a wrong answer was given; even if they “tweak” some weights to “fix a problem,” this can easily mean that they may create two or three new ones, since the same weights may participate in encoding multiple pieces of knowledge – the connections that have “learned” about the weight of steel may also have “learned” about its processing, so tampering with them might mean that the network, after “correcting” the issue regarding weight, will also “know” that the best furnace for steel is a steam engine. The fortunate aspect in this case is that this kind of error is easily and immediately detected by human operators, even if correcting them presents problems. The unfortunate aspect is that these errors constitute only one category of errors among those that language models fall into. There is also a category of more insidious errors which, although stemming from the same cause as the previous steel example, are much harder to detect, especially when the generated text concerns more specialized issues. To give a somewhat grotesque and rather exaggerated example, suppose a language model produces the phrase “acetylcholine is a neurotransmitter produced in the lymph nodes, spreads through the bloodstream, and regulates egg production in the ovaries.” Obviously, to someone relatively unfamiliar with human physiology, such a phrase seems very “scientific” and plausible. In reality, it is a complete fabrication with absolutely no basis, requiring a somewhat more experienced eye to identify it as such. Language models, however, have no hesitation in producing such “knowledge” (though perhaps not so crudely), even citing relevant bibliography, which in essence may say exactly the opposite—a fact that the models cannot comprehend.

The issue becomes even more “ticklish” in cases where the generated text contains a high degree of accurate information (thus initially persuading even a specialist), while at the same time there may have been inserted here and there some “inaccuracies” (and yet these too are always documented, with references to sources). Under a regime of widespread suspicion regarding the accuracy of what these models “say,” it is naturally out of the question to consider their potential use (at least for now) in any field requiring a minimum level of reliability (e.g., for medical diagnoses).

For proponents of deep neural networks, the solution to such problems is obvious: we need more data to train the networks and perhaps even larger networks. This is not an entirely unfounded position; the leaps that neural networks have made in recent years are largely due to the discovery of new architectures and techniques that allow them to consume vast amounts of data, such as those generated nowadays by every small or large device. But to what extent can this logic of scaling up go? Some initial research suggests that neural networks may already be reaching their limits in terms of the marginal benefit they gain from scaling tactics. From a more philosophical and political perspective, the notion that learning and intelligence are the result of simple accumulation of empirical data presupposes certain anthropological-type assumptions that are far from self-evident. This is, of course, the old and familiar extreme version of empiricism that has enjoyed (and continues to enjoy) great success in the Anglo-Saxon world: the entire world is built upon conventions that people accept (no notion of a priori categories is considered plausible), and which can be learned simply and solely through exposure to relevant data. This empiricist form of conventionalism automatically implies that the learning subject has no “pre-installed” perceptions and that it possesses extraordinary plasticity – not coincidentally, the concept of plasticity has held a prominent place in neuroscience in recent years.

For some, like Marcus mentioned above, an alternative would be to combine neural networks with symbolic logic systems, that is, systems that work directly on logical-type rules (somewhat more complex than those of Boolean algebra) which were once, before the recent surge of neural networks, quite popular in the field of artificial intelligence. The hope is that if the artificial brain is equipped with logical rules, then it will be able to avoid the evidently unreasonable conclusions that neural networks sometimes reach. Even if the combination of neural networks and symbolic logic indeed offers some advantages, it is by no means certain that unreasonable conclusions will be avoided. The reason is that the evaluation of a conclusion as logical or unreasonable does not occur exclusively and solely at the level of formal logic – as Mauss and Durkheim have shown, the way a particular logic is structured and its basic categories are never free from social influences, from the needs of the social group that uses that specific logic. It is not at all uncommon (either as an anthropological phenomenon in distant and “exotic” societies or even as a phenomenon of everyday social interaction in Western societies) for a discussion to lead formally correctly to a conclusion (e.g., that the idea of Soylent Green is excellent and should be immediately implemented), yet for this conclusion to be unacceptable to some of the participants for extra-logical (but not necessarily unreasonable) reasons; thus initiating a process of finding exceptions and peculiarities so that the logical chain leading to the (socially) evidently unreasonable conclusion breaks at certain points.

A different issue that is not resolved by adding symbolic logic concerns whether what is called “intelligence” reduces to manipulations of numbers and symbols, devoid of the body and its own needs and capabilities. It would be rather excessive to claim that an intelligent move made by an athlete on the field is the result of logical and numerical calculations on their part (or that physical movements do not constitute a sample of intelligence at all). On the other hand, the hypothesis that such calculations may occur at an unconscious level, although plausible, should at least be confirmed in practice, something that has not been done to this day. As it is understood today, “intelligence,” although it is essentially understood empirically, simultaneously incorporates the classical dualism of body and spirit, with the latter naturally having the primary role3.

A key reason why modern artificial intelligence systems, such as large language models, cause such unease has to do with the deeply ingrained body–spirit dualism that still distinguishes Western societies, despite the oaths of faith they occasionally pledge to various materialist philosophies. The automation and robotization of the production line during the third industrial revolution generated some anxieties about (manual) jobs that would be lost, but not a sense of existential threat (this found some degree of expressive outlet mainly in art). Large language models do not merely handle robotic arms, nor do they recognize cues in images or a few voice commands. On the contrary, they give the impression that they produce meaningful discourse and that they can do to the “spirit” whatever tailoring did to the body. In this way, they strike at one of the last refuges that the modern meta-slave had preserved for himself: that his spirit (and intellectual labor in general) holds a special place in contrast to the expendable body, and that it deserves special treatment—that with it, one can build palaces and self-define as one wishes.

How exactly a post-academic will psychologically handle the transition to a world where their degrees, cultivation, and knowledge, as they knew them until now, will henceforth have little reflection is an issue that perhaps does not particularly concern many beyond themselves. The certainty is that some other suitable and convenient ideology will be found to serve such needs. However, the issue of language mechanization itself is far broader than the concerns of any imaginary “intellectual” person. An example of the application of new language mechanization techniques also concerns the production of literary works. Tools such as ChatGPT and GPT-3 have been used in recent years to provide a helping hand to aspiring authors when they get stuck and cannot come up with a new idea, when they are tired of dealing with some more trivial parts of their book (e.g., describing a city), and generally whenever they need an increase in their productivity; usually these are authors who specialize in specific genres (e.g., high fantasy, cyber noir), have a specific audience with its own demands, and must produce new volumes almost at TV series rates – some of them have calculated that if they delay releasing their next book for more than four months, it will mean a reduction in their audience and therefore their income. However, the texts “written” by these authors have been produced by tools that in turn have been trained on textual data, that is, on earlier literary texts written by human hands. Therefore, to whom do the rights of the produced text belong? To the original authors who provided texts for the training of the models, to the authors who used these models, or perhaps also to the engineers who designed them? Sooner or later, any legal issues that arise will be resolved4.

From a political perspective, however, it is perhaps more critical that these language models function as primitive accumulation machines; accumulation of linguistic wealth. Some might certainly get the idea that, for this process to be fair, those who produce primary linguistic data (i.e., potentially those who speak) should perhaps be compensated. Similar ideas have indeed already been formulated generally for motion data. Just as farmers were protected by fences in England because some agricultural law was established, so too are those who speak this or that language expected to be protected. The voice of the machine is furthermore predicted to be very sweet and “safe,” without ideological distortions and intellectual temptations, always in the name of diversity and inclusion.

Separatrix

- All images accompanying the text, except for the neural network diagrams, have been generated by us with the help of DALL-E 2, an artificial intelligence model that produces images based on a description provided by the user in the form of text. ↩︎

- See also the related article “LaMDA scandal: do neural networks see nightmares?“, cyborg 25. ↩︎

- There is also the (somewhat marginalized) branch of so-called embodied cognition, which considers the body as indispensable for the emergence of intelligence. Consequently, it views robots, with their materiality, as the most suitable path toward constructing thinking machines. Although this approach is more intriguing, the question remains as to how a physical construct, such as a robot, could develop certain basic “instincts” and a value system that would allow it to move and interact within the world. Introducing programmed rules into a robot’s “brain,” such as “avoid movements that could harm you,” as a metaphor for the need for self-preservation, would be a technical solution of sorts, yet it does not seem very convincing from a philosophical standpoint. ↩︎

- The first related legal dispute has already begun in Britain. It concerns the use of images from the Getty page (one of the largest repositories of original images) for training image generation models and the issue of who owns the rights to the new images or whether companies that use the original images as “training material” have the right to do so without permission. See the article in Financial Times “Art and artificial intelligence collide in landmark legal dispute“. ↩︎