Will smart machines produce value?

Despite the plethora of related analyses, the entire discussion (at least in mainstream media) around artificial intelligence seems to have reached a dead end, trapped in certain repetitive patterns which it reproduces with tiresome persistence. Almost everyone appears to be (or pretends to be) certain about the unstoppable progress towards the 4th industrial revolution and the cataclysmic changes that artificial intelligence will bring along the path to “smart” living in general. As if possessing some mythical Midas touch, wherever artificial intelligence extends its hand, approximately cosmogonic transformations are expected; the declared purpose, after all, is for every human behavior and habit to eventually become subject to algorithmic manipulations, to pass through multiple levels of “smart” intermediations before being allowed to leave its imprint on the real world.

For the overwhelming majority of those who have a (direct or indirect) involvement with the processes of developing and promoting related technologies, any reservations about the course of this “progress” are naturally unthinkable. The natural and desirable destination of “smart” technologies is to become as common as electricity itself. The opposite (but not contrary) motif against the over-optimism of those who benefit from the “miracles” of artificial intelligence usually takes the form of catastrophism: if we leave the relevant technologies unchecked, there is a very real risk that they will ultimately devour humanity itself and perhaps even replace it with more advanced intelligent beings, possibly freed from the burdens of bodies and their obsolete biology. On the other hand now, all the fuss around artificial intelligence has led to a (justified, to some extent) skepticism. In its most extreme version, this skepticism is entrenched behind the logic of “more of the same”: the 4th industrial revolution with its smart technologies constitutes yet another technical restructuring of capitalism, which does not touch the core of its operation but only its “external” aspect, the forms and ways of exploiting labor power.

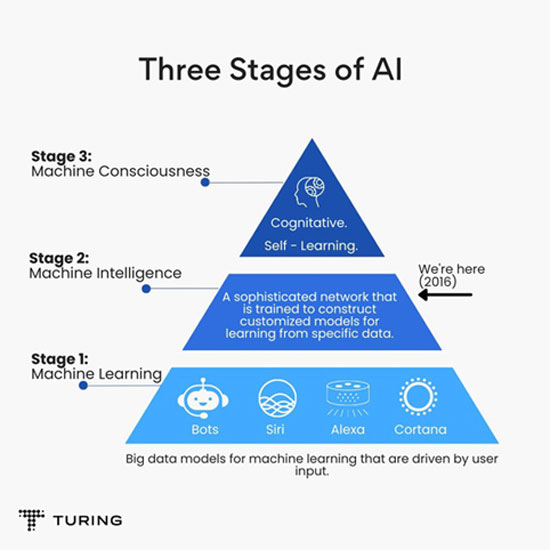

This tension between the two interpretations of artificial intelligence, with one pole occupied by the perception of “forget what you knew, everything will change” and the other by that of “more of the same,” permeates to a large extent many Marxist analyses1. Nor are those lacking who, inspired by certain passages of Marx in Capital and the Grundrisse, see the universal digitization as the rope that capitalism itself passes around its own neck and thus roughly as an opportunity for transitioning to a post-capital communist society. Especially for Marxist critique, however, engagement with artificial intelligence is not simply a matter of fashion and accepting or rejecting the perceptions of the herd, as it touches upon a crucial issue: that of who ultimately produces value and thus who constitutes the object of exploitation. For Marx himself, neither machines nor animals nor even slaves produce value. No matter how much they produce labor in a sense, they still do not produce value in the capitalist meaning of the term. For a subject to produce value through its labor, at least two conditions must be met. First, it must be an autonomous subject with a repertoire of behaviors that exceeds the reflexive reactions of instincts and the routines of mechanically repeated movements—something that obviously does not apply to machines and animals2. Second, it must be “free” to sell its labor power in order to survive, that is, to have entered the legal relation of wage labor through which part of the value it produces is expropriated—an arrangement that does not apply in the case of slaves or serfs.

But if technological evolution reaches the point where it can produce machines with real thinking ability, machines that could even demonstrate imagination; what would this mean for Marxist analyses of value if artificial general intelligence (AGI) were to appear—artifacts capable of replacing any human in any job (according to one definition)? If such “perfect” machines were ever constructed, machines that would have the status of autonomous subjects (and would therefore cease to be mere machines), then obviously they would be (at least potentially) capable of producing value. And thus, they could also be proletarianized.

Test, and more tests

Various scenarios can be imagined regarding this labor issue, particularly in relation to the types and forms of exploitation that may emerge. However, attempting to answer the question of whether sentient machines can be constructed in an absolute, general, and indefinite way constitutes rather a futile exercise in futurology—and thus also in bad metaphysics. More interesting and politically crucial is to understand the terms and conditions under which the current discussion on artificial general intelligence is taking place, as well as any (explicit or implicit) ontological and axiological commitments made by those eager to provide easy and quick answers. Given that no philosopher, psychologist, or neuroscientist has managed to provide a strict definition of “intelligence,” this concept functions more as a malleable floating signifier that takes shape and form according to the needs (and interests) of whoever happens to use it. Therefore, examining these shapes can transform the exercise of futurology into an exercise in mapping the spasms of hypermature capitalism.

Turing’s famous article on machine intelligence holds an almost canonical position within related discussions, especially among those who passionately swear by the possibility of its construction3. As is known, in this article Turing proposed a test based on which it can be determined whether a machine thinks or not. A human takes the position of the examiner and conducts a written conversation with a machine and with another human. His goal is to manage to distinguish which of his interlocutors is the machine and which is the human. If the machine has such high dialogical abilities that it can deceive the examiner, then we are in a position to ascribe to it the attribute of intelligence. To those who might raise the objection that the machine may simply be simulating the ability to converse without, however, possessing consciousness of what it is doing, Turing responds with the disarming argument that we judge the intelligence of our fellow humans in the same way. We converse with them without dissecting their interiors to discover somewhere a hidden intelligence; on the contrary, we make the generous concession of considering them intelligent. Extending this argument of his shrugging of the shoulders, there are not a few who believe that technical development will ultimately render such disputes meaningless. When machines reach the point of adequately mimicking every human behavior, then the inquiry regarding whether somewhere within them a “mind” resides will degenerate into barren scholasticism. Most people will simply naturally consider that they indeed possess intelligence.

The Turing test, however, is not the only one of its kind. Similar thought experiments have been formulated even with robots, thus bypassing the issue of language and speech. One such example is the (less well-known) Braitenberg vehicles (named after the scientist who introduced them)4. These are primarily conceptual robots (they were not actually built, at least not initially), and are extremely simple in their design. They possess a few sensors to detect certain stimuli from their environment (e.g., light sources), which are connected to the robot’s motor components (e.g., its wheels). Braitenberg started with some simple configurations in which a stimulus directly triggers a simple command to the robot’s motor part – for instance, if the left sensor detects a light source, it connects to the left wheel and causes it to move backward. From these simple setups, he progressed to increasingly complex ones (e.g., the left sensor connecting to the right wheel with a command to move forward), but they always remained based on simple sensors and basic movement commands. Only their combinations and possible responses varied. In this way, he managed to show that such little robots, based merely on simple reflex reactions and without even possessing an internal processor, can exhibit a variety of behaviors, many of which appear to be purposeful (e.g., aggressive behaviors or attraction toward stimuli). To what extent, then, do Braitenberg vehicles differ from an insect attracted to a flower – at least from the perspective of an external observer?

Intelligence without body, without consciousness

Mental experiments such as those of Turing and Braitenberg certainly have the advantage of immediacy and intuitive obviousness. Their drawback, on the other hand, at least for those who enjoy precise formulations and rigorous thinking, is that they never say exactly what they mean. One only needs to scratch a little beneath their surface to go beyond the wall of “immediacy,” and immediately one will encounter terminological ambiguities and semantic contradictions. Still, even so, one can discern a basic core of common assumptions—regardless of whether they constitute a coherent whole or are based on some flawed reasoning.

One of these assumptions concerns the materiality of any intelligence. In order to speak of intelligence, it must necessarily be manifested upon a material substrate. At this point, however, caution is required. The assumption of the materiality of intelligence does not necessarily imply commitment to any particular materialist ontology. It is a very specific kind of materialism, called upon to function as a support for intelligence, known as “physicalism.” Whether we speak of a machine that converses with humans or one that moves “autonomously” in space, in every case we are talking about machines. The implicit assumption here is that, to begin with, a valid understanding of nature presupposes conceiving it in mathematical—mechanistic terms. In terms of formal logic, this would be the major premise of the entire argument. Secondly comes the minor premise, which asserts that the mind (often identified with the brain) is also part of nature. The conclusion is inescapable: therefore, the mind must also be understood in mechanistic terms, as a machine whose laws we must discover if we are to understand its operation.

The fact that the philosophy of artificial (general) intelligence borrows the prestige of the natural sciences seems to be a good card in its hands. However, it doesn’t solve all problems, especially if one doesn’t go all in and enter the game with their remaining money, determined to see all the cards open. Even if it is accepted that the above reasoning has a validity to the extent that it refers to the brain – the only material complex to which intelligence can perhaps be attributed – this is not self-evidently transferable to the case of mechanical complexes. Therefore, the common ground between the brain and any mechanical mind should be located at another level, beyond that of their materiality. In this way, however, a gap necessarily emerges, a dimension between intelligence and biology. Intelligence is not reducible to biological functions, although it uses them almost incidentally, as a means of “expression.” The gap becomes even more pronounced with the formulation of the following naive question: do we have the right to refer to a baby born through artificial insemination as a sample of artificial intelligence? The answer is obviously negative. Nevertheless, such a baby obviously possesses intelligence and has obviously emerged as a result of some technical intervention. The distinguishing feature compared to what is usually called an intelligent artifact is rather that the technical intervention in the case of artificial insemination occurred once, after which nature was left to follow its course, without being predetermined at every step. In other words, it is the difference between “cultivation” and “construction”; somewhat abusively, one might speak of a baby that is cultivated (just as one grows a tree), but certainly not of one that is constructed. The exact opposite would naturally apply to a sample of artificial intelligence. The baby ultimately seems to suffer from excessive biology and excessive nature to be granted the label of the artificial.

The chain of gaps, however, does not stop at the abstraction of intelligence from its biological substrate and at the distinction between the animal and the artificial or constructed. If this distinction is initially accepted, then almost inevitably another one arises. That between intelligence and consciousness. The observation that only living beings, with their so “outdated” biology, exhibit purposeful and forward-looking behavior is certainly a commonplace. Yet they engage in the world through forward-looking relationships only to the extent that mortality constitutes a permanent condition of their existence. A being without any sense of mortality whatsoever would be a being that would know no limits and would have absolutely no desire, not even a self-preservation instinct. It could mix with its environment in every possible combination and therefore would have no sense of self, not even in an instinctive form. In fact, therefore, it would not be possible for it to have any form of consciousness, being simply a thing, an object without subjectivity. With a similar logic, a machine that does not need the biology of the animal cannot have any sense of mortality nor any will of its own; hence, no form of consciousness either. The price for the de-biologization of intelligence is also the “relief” of consciousness from it.

Another naive question might be useful at this point. Based on the criteria of artificial intelligence, does a person suffering from severe intellectual disability have intelligence or not? They obviously possess consciousness; however, no engineer would make the mistake of administering the Turing test to a machine with such a “low IQ.” It would fail spectacularly, whatever that says about how much “humanity” is embedded in the intelligence that engineers have in mind.

On one hand, then, intelligence. On the other, consciousness, biology, and life itself—things that intelligence doesn’t even require. Yet it seems as though it, too, has almost been dematerialized. Despite oaths of faith in a kind of materialism, no material basis appears to remain for the mind to stand on. For if it is not necessarily bound to the body, but can also be mechanically expressed, then the logically consequent step becomes obvious. Neither transistors, servomechanisms, nor wires constitute any necessary precondition for the emergence of intelligence. Just like the brain, semiconductors at best play the role of the contingent. They could be replaced by some other material. Intelligence, therefore, needs some material medium in order to manifest, but its essence transcends matter from above. The philosophical way out of this suspicion of neo-Neoplatonism (the double use of the prefix “neo-” here is not redundant) is the proposal of functionalism: the core of intelligence is now assumed to lie in the way it functions, regardless of the medium through which its operational rules are implemented. This often means that the mind is identified with the algorithmic manipulation of symbols based on strict and discrete steps. Just as one can drive a car regardless of whether an internal combustion engine or an electric motor lies beneath its hood and still speak of a car, so too does intelligence possess a variety of “means of expression,” both biological and electronic.

Let us suppose, to begin with, that the introduction of functionalism is accepted and that suspicions that we are dealing here with yet another application of “saving the phenomena” are set aside. However, are we still certain that the Turing test and Braitenberg’s little robots continue to convey what was initially assumed? With the same ease that Turing bypasses “scholasticisms about consciousness,” one can offer the exactly opposite interpretation. Since we know with certainty that a speaking machine or an assemblage of reflex movements, such as these little robots, possess not even a trace of consciousness (after all, we constructed them), the only safe conclusion that can be drawn from such thought experiments is that the ability to simulate a behavior tells us absolutely nothing about that behavior itself, nor does it offer any clues for understanding it. To regard GPT as an intelligent machine simply because it can conduct an elementary conversation with you would be as naive as the reactions of early cinema audiences fleeing the screen when they saw the train approaching them. What these tests actually measure is not the intelligence of machines, but the gullibility of humans5.

Similar objections regarding the ability of simulation to actually approach what it is supposed to simulate have been raised in the past by philosopher John Searle in his own famous thought experiment of the Chinese room. In it, he asks us to imagine a man locked inside a chamber, along with a rule book that tells him (in English) the rules according to which Chinese ideograms can be combined to make sense in the Chinese language. He himself knows nothing about what these symbols mean, relying only on their appearance and shape to apply the rules in the book. The equivalent in Greek would be as if someone gave him a card inside the chamber with the phrase “Hi, how are you?”, he would visually match the Γ, the ε, the ι, etc., would look up in the book, see that after this sequence of shapes follows “Καλά” (fine), and then he would take a Κ, an α, a λ, another α, put them in order, and give them out on another card. Searle’s question was this: do we really have the right to say that such a man knows how to speak Chinese merely because he would give the impression of conversing with a Chinese person by exchanging cards with ideograms? Obviously not. Since the enclosed man is unable to grasp the meaning of what he is doing, there can be no talk of understanding the Chinese language. Some (such as philosopher Daniel Dennett) have attempted to rebut the negative conclusion of the Chinese room by resorting to the concept of the system. Granted, the man does not know Chinese, but this ability can be attributed to the entire “system” of man – instruction book – chamber. However, it remains difficult to grasp what kind of system this is in which there is no necessary structural or functional organization of the parts toward the whole. Searle himself had responded with yet another variation of the experiment, considering that there need not even be a chamber or instruction book; it can be assumed that the man has memorized all the instructions. What exactly is the “system” in this case?6

Intelligence in the laboratory

In any case, the introduction of functionalism into the relevant argumentation rather aims more to make plausible the conclusion that it is indeed possible to simulate intelligence. Provided that it is relieved from the burden of biology and from the “vitalism” that necessarily exists in it to a lesser or greater extent, then the way opens up for its mechanical-type constructability. The implicit question that seems to be formulated by functionalism is condensed as follows: perhaps intelligence ultimately reduces to mechanical laws, given that we have shown that a kind of intelligent behavior is exhibited even by artifacts constructed in a completely mechanical way?

The issue of consciousness, however, remains pressing, at least if by the term intelligence we mean so-called general intelligence (which, as already mentioned, could produce value and be an object of exploitation). If (general) intelligence is considered constructible, then the same should apply to consciousness. Consciousness, however, can constitute itself as such and constitute the meaning of its own existence only in reference to something external to it—for any attempt to constitute meaning presupposes that what is called upon to be meaningful relates to something external to itself. The absolutely external for consciousness is, of course, its death, the sense of the finite. For an artificial consciousness, the external in relation to it would be its creator. Already here, certain metaphysical tremors7 resonate. The creators of “smart” artifacts more or less aspire to take the position of quasi-divine beings in relation to their creations; their ambition is to build rational beings, almost as in the Christian doctrine of creation, where God fashioned humanity. The belief in the possibility of simulating anything, to any degree of clarity, constitutes a metaphysical faith in omnipotence. It is a gesture of denial and an inability to recognize limits and finitude, anything that exceeds the capabilities of homo faber.

If read backwards and with a more historical eye, this sense of constructive omnipotence essentially constitutes the dream of every social engineering, since it intensifies the sense that subjects (human subjects) can be equally easily transformed into objects of manipulation – do they not indeed have a functional equivalence with artificial subjects? In more Marxist terms, the notion of universal constructibility (even of consciousness) leads to an extreme form of realization – nothing can escape the fate of being transformed into a thing; therefore also into a commodity with exchange value. If finally something must be questioned in Marx’s analyses, it is not so much the distinction he makes between human on the one hand and animal or machine on the other, but his enlightening faith in the constructive omnipotence of human labor. The “refuge” of consciousness is precisely that it cannot be constructed.8

However, a symptom of actualization is also Turing’s response that even human intelligence is judged by its external behavior, without needing to enter into their minds to ascertain that they indeed think. With this observation, Turing responds to those who prioritize the need for a theory of the mind (as it is commonly called) on behalf of intelligent creations, that is, the need for every such creation to be able to represent within itself the mind of other, similar creations, and thus know that they too think in the same way. This way of formulating the issue of “intersubjectivity” is extremely misleading, regardless of what the final answer may be regarding how the intelligence of another being is judged. The reason lies in the fact that “mind” is perceived as something enclosed, as an atomic property. The emergence of the atomic mind always precedes its encounter with other beings and their own consciousness. Such a perception seems natural and self-evident only in societies where the fetishism of the Ego has itself become absolutely “natural” — in other words, only in societies where the self has been reduced to autonomy; hence, also to value or even to capital for exploitation. But the mind does not necessarily have to be conceived in this way. On the contrary, the prerequisite for every individual consciousness is the “social mind.” The individual mind is “built” (metaphorically speaking) only through its engagement with its environment and through the social relationships it gradually develops, without ever needing to confirm only retroactively by some test that other subjects resemble it and are not deceiving it. Such a suspicious consciousness would already be a heavily pathological consciousness, which would radically be unable to exist within the social world. The fact that such a pathological stance of consciousness becomes something absolutely “natural” says more about the society that gave birth to it than about the ontological status of consciousness itself.

Denial of machines or faith in machine denial?

No, then. It is not expected in the near future for proletarianized artificial consciousnesses to make their appearance. Artificial intelligence, to the extent that it is unable to develop a core of subjectivity along with the corresponding capacities for reaction and refusal (and it is difficult to imagine how it could accomplish this), is also incapable of producing value. Labor relations and the production of value constitute, above all, social relations. Accumulated capital, despite its seemingly substantial form, also constitutes a social relation: it is a legal form for the claims that its possessor can raise against other capital holders and, above all, against those who possess no capital except their own labor power. Claims regarding the disposition of their time and their share in the produced social wealth. Bees may produce work but not value, because their work constitutes an occurrence within human relations. The “subjects” of artificial intelligence, insofar as they do not participate in the spectrum of social relations, cannot raise either claims or demands. They cannot become objects of exploitation because they are merely objects.

From this perspective, those who treat artificial intelligence as “one of the same” have a point. Indeed, it is not difficult to imagine the 4th industrial revolution as yet another offensive by capital, aiming ultimately at the expropriation of workers’ knowledge, this time targeting so-called “intellectual” labor. Symbolic machines thus resemble battle tanks in their advance to dismantle any notion of meaning in work. It would, however, be shortsighted not to recognize the enormous new fields of exploitation that open up along with the qualitative changes that will occur, not only in the concept of labor but also in social life in general. As capital’s organic composition increases, with the introduction of all kinds of machines for the slightest tasks, always controlled by some invisible center, the field of labor becomes increasingly polarized: on one side, an elite of privileged and well-paid managers, and on the other, a permanently underpaid mass of interchangeable “cyber-serfs,” for whom the savage extraction of surplus value would become a permanent condition and inescapable fate9. And if they think they will at least be able to dispose of their free time as they wish, they are sadly mistaken. Because the appetites of artificial intelligence do not stop at work. Every movement and point traveled, every purchase, every click, every second of attention to a video, every emotional reaction to a social media post, every social behavior in general (must) be converted into data from which profit must somehow be extracted; hence, they also become objects of manipulation, all the more indispensable as the demands of wealth producers over “real reality” shrink.

Behind smart devices, smart cities, and the universal connectivity blessed by artificial intelligence lies a far less dazzling future. That of a “frictionless capitalism,” where the cycles of reproduction, production, circulation, and realization of value will be coordinated with such mechanical precision that the social factory will have moved into its just-in-time phase. No delays, no setbacks, no waste. Above all, however, no sabotage. Because it is obvious that “failures” will still exist, possibly even on a massive scale, since universal connectivity will turn every point of the social “network” into a potential source of error. Yet at the very least, these “failures” will always be able to be regarded as the result of some “technical” mistake. Never again, however, the result of a refusal.

Separatrix

- For a more thorough examination of Marxist analyses on the topic of artificial intelligence, see Inhuman Power: Artificial Intelligence and the Future of Capitalism, Nick Dyer-Witheford, Atle Mikkola Kjosen, James Steinhoff, Pluto Press, 2019. ↩︎

- Although some objections have been raised regarding the animals. ↩︎

- See the article by Turing “Computing Machinery and Intelligence.” A fuller understanding of intelligence would require an analysis of the philosophical and social history of this concept. We will not attempt such an excavation here. A brief overview can be found in a previous issue of Cyborg. See “The Turing Test: Notes on a Genealogy of ‘Intelligence,'” Cyborg, vol. 8. ↩︎

- See the booklet by Valentino Braitenberg Vehicles: Experiments in Synthetic Psychology. ↩︎

- See The mind’s provisions: a critique of cognitivism, Vincent Descombes, Princeton University Press, 2001. ↩︎

- The problem with Searle’s objections is that he himself ultimately shows a particular insistence on the centrality of the brain. He seems to reject anything that is now considered a sample of artificial intelligence because there is no biological brain within which some mind resides. However, the centrality of the brain has its own problems. It is not necessarily a brain that thinks, but a whole body that thinks and acts (and never just one or the other), that interacts with other bodies, enters into social relationships, and lives generally in an environment and converses with it. From this perspective, the brain can be considered “simply” as a coordinating organ of the body, but not the “part where intelligence resides.” This is much more diffuse. For similar criticisms against the centrality of the brain, see the works of Alva Noe (Out of Our Heads: Why You Are Not Your Brain, and Other Lessons from the Biology of Consciousness, quite accessible), Vincent Descombes (The mind’s provisions: a critique of cognitivism, deeper and more demanding) and Hubert Dreyfus (What Computers Can’t Do: The Limits of Artificial Intelligence). In one way or another, all these works draw their origins from Merleau-Ponty, Heidegger and Husserl. ↩︎

- Beyond the logical error that also exists, a confusion of semantic levels. In the case of human consciousness, meaning is constituted with respect to something fundamentally external to it. In the case of artificial consciousness, meaning is constituted with respect to something internal (the human consciousness of the creator), assuming that mechanical and human minds do not differ essentially in anything. ↩︎

- Since tests have such a prominent place in discussions about intelligence, let us also add our own test regarding consciousness. We’ll call it the Lazarus test. How is it possible to test whether a being possesses consciousness? If we kill this being, is it possible to restore it afterwards exactly to its same form, even if we try with all our might? If the answer is affirmative and we can reconstruct it, then it did not possess and does not possess consciousness. If the answer is negative, then it did possess consciousness; in which case, of course, we have also proven ourselves to be murderers, apart from being examiners… And because it’s easy to play around with these tests, here is another one. Let’s call it the mind snatcher test. The question now is as follows: is it possible to completely enter into the mind of a being, to know exactly what it is thinking down to the smallest detail? For truly intelligent entities, the answer must be negative. They always possess a core of irreducible subjectivity. In the case of a non-intelligent machine, it is always possible to examine all inputs and internal states and understand what it “thinks,” as well as to predict how it will react. ↩︎

- Resistance capabilities will always exist of course. The issue is from what point each time the defense and counterattack begins and how many territories will have been conceded in the meantime. ↩︎