Galileo’s and Descartes’ laws of motion, Newton’s law of gravity, Maxwell’s laws of electromagnetism, Mendel’s laws of genetics, the laws of thermodynamics, the laws of reflection and refraction of light rays… The average social perception, as shaped by the educational (and ideological) system, understands nature roughly as Galileo did: as a book whose text is written in the language of mathematics. An alternative analogy might perhaps be that of a labyrinth that keeps certain secrets well-guarded behind various doors. One only needs to discover the equation-key that fits each lock in order to gain access to nature’s innermost sanctuaries. In any case, regardless of whichever metaphor one wishes to employ, nature is perceived as something initially inaccessible to humans, to which they do not have direct access. However, mathematics allows them to lift the veil of confusion and discern the harmony of nature, which, at a secondary level, ultimately operates on the basis of firm and unbreakable laws. At this level of order and smoothness, there is no room for doubt or exceptions. Law is law, and its power is compact, unified, continuous, and seamless both in space and in time.

This essentially legal or even Hobbesian conception of nature as a unit that maintains its coherence thanks to an omnipotent, omniscient “Leviathan” does not seem to have suffered any blows, despite the fact that the laws in question do not display the absoluteness and stability that Descartes, Newton, and Kepler would have desired. The dry and monotonous linearity of Newtonian space-time has ultimately given way to the captivating curves and curvatures of relativity, while the famous dogma of biology (which unidirectionally channeled cellular function exclusively from DNA to proteins and forbade the reverse direction) has long since run its course, allowing cells to lead their degenerate lives by occasionally incorporating genetic material even from viruses. For those who remain faithful to ideas of scientific (and, as is often implied, moral) progress, such paradigm shifts are nothing more than episodes within the adventure of accumulating knowledge. Each new paradigm simply perfects the previous ones, adding new tiles to the mosaic of human knowledge, without negating what came before. We will not dwell particularly on this issue. The scientific enlightenment that saw in technoscience the embodiment of absolute rationality and the archetype for all forms of knowledge has suffered the criticism it deserved, even if such criticism has not taken deep root in the social imaginary or is often expressed in its most vulgarized and distorted form. The variously named “laws of nature” also need their periodic revisions, something that occurs not merely due to empirical inadequacy or rational inability to explain certain phenomena. Extra-scientific and broader social factors may play an equally significant role.

The above findings are more or less familiar and almost trivial to those who have dealt, even minimally, with what is commonly called in academic circles the “sociology of knowledge,” which refers to what was once simply known as critical thinking (even in opposition to science itself). The issue, however, can take on broader dimensions. If the laws of this or that science exhibit conceptual shifts, and thus their validity is necessarily relativized and can only be understood within specific historical conditions, then could something similar also apply to the very concept of natural law itself? From Aristotle to Newton, and from Newton to Einstein, the laws governing the motion of bodies in space-time have been expressed in radically different ways, and nothing excludes (in fact, it is rather certain) that relativity too will someday be considered obsolete and replaced by some other theory. But would it be possible for the very notion that nature is governed by laws to become obsolete altogether? And if this is indeed possible, could it occur only as a result of a regression into the shadows of anti-scientism and irrationalism, or perhaps also as the outcome of a perfectly healthy and entirely rational historical process?

The story already indicates part of the answer. Human societies have only learned to live within “natural laws” over the last three centuries. It would take strong doses of arrogance and shortsighted self-love to consider that all of human history up until the 17th century can be summarily described as “irrational” simply because it was unaware of a nature governed by laws. However, recognizing that natural laws were absent from social perceptions does not, of course, imply that societies had no relationship whatsoever with ideas about regularities in nature. No society exists that has not developed at least elementary “theories” about natural phenomena and their repeatability; naturally exploiting for its own benefit the predictive possibilities offered by natural regularities. Nevertheless, the concept of natural laws is only one possible way for societies to express these natural regularities. It certainly isn’t the only one and, as might be expected, bears the clear imprint of the historical era that gave birth to it1.

Perhaps the most striking reversal of the relationship between law and nature, as we have inherited it from the 17th century in the complex of “natural law,” can be found in ancient Greece and specifically in the current of sophistry. One of the basic opposing dualities that the sophists brought to the foreground was that between nature and law, to such an extent that the phrase “law of nature” would sound as a contradiction in terms to their ears (and not only to their own). As a word, law referred mainly to what we would today call a social contract or, in other words, to the rules of behavior imposed by the prevailing social norms. It was certainly not an innocent and simple observation on the part of the sophists, of the kind that is expressed with detached objectivity in order to conclude with commonplaces such as “all societies follow certain rules.” The relativism of sophistry had also an intensely “enlightening” intention, insofar as it aimed, according to the famous saying of Protagoras, to set man himself as the measure of judgment of all things; rejecting, in other words, metaphysical doxas and references to transcendent ideas. For the sophists, the dominant morality that drew legitimization from religious perceptions was nothing other than a convention (a law) that had been imposed almost by coup in order to ensure specific interests and not due to some rational superiority – with a small dose of exaggeration, one could argue that the sophists were the first anatomists of ideology as false consciousness. The opposing counterpart of law was nature, which was also the only one that could indicate the real interest of any subject. Nature was the refuge that the sophists found not only for strictly epistemological reasons but also for political ones.

One objection at this point would be the following: the fact that the sophists used the word “law” with a special meaning which does not necessarily coincide with its current meaning does not mean that there was no idea of natural laws at all, perhaps expressed with different terminology. The objection is partly correct. Indeed, there was a perception of regularities in nature as well as an attempt to explain them. However, it was embedded in a very different conceptual framework. Aristotelian epistemology, which essentially dominated the West until the Renaissance, did not perceive behind the natural order of the world a set of inviolable rules. The possibility of error and deviation from the usual course of nature was never zero, as was empirically confirmed, for example, in cases of births of infants with deformities. Even greater significance, however, is Aristotle’s analysis of the various kinds of causes by which natural phenomena can be explained. Suppose I have a statue in front of me. How can I explain its presence? What are the causes for it being there? Based on Aristotelian epistemology, the causes of the statue’s presence can be distinguished into four categories. First, the statue has a material substratum. The marble from which it is constructed constitutes its so-called material cause. Second, some sculptor undertook to work on the marble to extract forms from it and produce the final result that I see. The sculptor constitutes the efficient cause of the statue. Third, what makes the statue a statue, beyond the material from which it is constructed that has already been mentioned, is also its form. If I have Michelangelo’s David in front of me, with his ambiguous gaze that seems to hover between severity and scorn, then David (his form) is the formal cause of the statue. Finally, there is also some purpose for which the statue is in front of me: that of aesthetic enjoyment. The aesthetic enjoyment I seek as I vainly attempt to meet the gaze of David, who always looks beyond me (his height is over 4 meters), in a kind of “emotional presbyopia,” is the final cause of the statue. As becomes clear from the above, behind Aristotelian nature there existed a universe of causes considerably richer than that of the absolutely mechanical laws of the 17th century. For modern physics, there is no room for formal causes and even less for final causes. However, this is also one of the reasons why it will eventually be able to speak of inviolable laws, provided it first manages to expel any notion of teleology and inherent action of material bodies (we will see more details below).

The position of mathematics and their suitability to describe or explain natural phenomena is, of course, another central point of differentiation of modern physics (and science in general) from its predecessors. The distinctive element of science in its contemporary sense is the fact that it was established as an amalgamation of mathematics, natural philosophy, and the experimental method. Despite the fact that mathematics were certainly known in the ancient world, having even reached a high level of sophistication, they were never considered suitable as a means of describing the natural world or as a method for causal explanation of natural phenomena. The high status they held in the value hierarchy of the pursuits of a free citizen was not due to their offering a path to understanding nature, but rather because they expressed the robustness of human reason, which could arrive at certain conclusions through strict logical implications. For certain philosophical schools, however (albeit rather minority ones, truth be told), such as the Pythagoreans and Platonism, numbers, shapes, and their relationships constituted a particular order of the world even more real than that of immediate sensory data. Mathematics, therefore, were understood either as a game of reason and its autonomy, or as a pathway to a metaphysical reality. In both cases, their explanatory power regarding nature was nil. The chain of logical steps contained in a mathematical proof was in no way connected to a chain of causes ultimately producing a natural phenomenon. In more modern terms, one could speak of a conception of mathematics that viewed them as a set of purely analytical, tautological propositions exploring the capabilities of (human) reason, and not of nature itself. Causal explanations were certainly not absent, but these were not based on the (non-existent) persuasiveness of mathematical proofs, but rather on the Aristotelian tetra-category typology mentioned above.

Complementary to the position held by mathematics was the position of experiment in ancient epistemology. Speaking absolutely, this position was simply non-existent. Aristotelian physics (and biology) may be based on a multitude of empirical observations, but it strikingly lacks any notion of experimental, controlled intervention in nature. Since nature was increasingly perceived as a kind of organism, the goal was to understand how it functions when left to follow its inherent tendencies, rather than when subjected to external interventions. The distinction between the natural motions of bodies (which they follow on their own) and the violent or artificial ones (which follow as a result of some intervention) was quite strong; the former were those worthy of in-depth study, a perception that resulted in the serious undervaluation of experimental control—for why focus on something that essentially disrupts what you truly want to study? This particular stance, of course, was not merely the result of an increased wariness toward the rhythms of nature and a tendency to identify with them. It can easily be read in more mundane ways, as a projection onto the ontological level of that social condition which saw manual labor (and the practical-technical knowledge it entails) as suitable only for slaves; for free citizens, the ideal condition was contemplation free from practical concerns.

Within this conceptual framework, where physical bodies possess their own inherent forces while simultaneously being subject to a variety of causal pressures, where space is distinguished by different qualities – let us remember that Aristotelian physics also had a typology of elements (air, fire, earth, water, quintessence/aether) based on which the motion of bodies in space was determined – and where mathematics and experiment have no place, it was inevitable that any notion of natural law could not stand. It is not coincidental, moreover, that the word “law,” although it was widely circulating in discussions related to ethics and politics, was absent from the “scientific” vocabulary and any use of it was made in the logic of opposition to “nature.”

Some initial timid steps toward the direction of connecting nature and law were already being made by the stream of stoicism, which first introduced the concept of “natural law.” Nevertheless, the purpose of this connection was not epistemological, but once again moral and practical. For the stoic philosophers, the model of the universe was analogous to the political model they themselves experienced: the entire universe was likened to a monarchical state governed by the (essentially moral) commands of a divine Logos. The totality of these moral commands, which every person can access through the Logos, received the name “natural law.” The other side of the legal coin consisted of all social institutions that might have a somewhat arbitrary character and did not naturally derive from the Logos; a contrast that naturally recalls the considerably later distinction between natural and positive law in modern political philosophy. This distinction would be taken up centuries later (13th century) by Thomas Aquinas, who gave it Christian hues by replacing the abstract Logos with the more personalized God. The Christian God is likened to a craftsman who has imbued the entire world with His laws; laws which, however, retain a clear teleological character, as in traditional Aristotelianism. Besides human positive law, there therefore also exists natural law, that is, the way in which nature and humans participate in the eternal divine law. Nature thus appears to acquire a legislator, but this is not yet mathematics, but the divine person. For now…

The revival of mathematics would not ultimately be delayed much (historically speaking) and initially expressed itself on two levels: the ideological and the practical-technical. On one hand, at the ideological level, there was towards the end of the Middle Ages a renaissance of Platonism, and thus of the mathematical realism embedded within it (numbers are real entities residing in the higher realm of Ideas). On the other hand, the Renaissance, partly freed from the negative connotations of manual labor, discovered the usefulness of mathematics when applied to technical work, such as mechanical constructions. These two developments seem contradictory to each other: mathematics was revived both for their ideological purity and for their practical utility! However, they have something in common. They are symptomatic of a broader tendency to break free from the suffocating embrace of Aristotelian physics and epistemology. At a philosophical level, the escape from Aristotelianism was also expressed by the current of nominalism, according to which all complex metaphysical constructions with their universal ideas are simply useless. What truly exists are only individual instances (this or that specific horse, and not some abstract idea of “horseness”) upon which the human mind arbitrarily imposes names (hence the term nominalism, meaning “naming”) in order to be able to handle them. The details are not particularly important at this point. What matters is that the name-rule (onomatocracy) of nominalism was simultaneously an atomocracy (in the sense that it rejected universals), the anti-Aristotelian perception, that is, that everything (even nature) can be decomposed into its ultimate constituent elements and then reassembled based on combinatory rules. The erosion of Aristotelianism through the vehicle of nominalism would prove to be an important first step towards the subsequent dominance of mechanism as an ideology.

The complete dethronement of Aristotelianism and the absolute triumph of mechanism would ultimately occur in the 16th and 17th centuries, the centuries traditionally considered the era of the scientific revolution. What is striking, however, is that no such revolution actually took place, if by that term is implied some abrupt rupture with the past. The notion of an irreconcilable hostility between the emerging scientific rationalism, with all its rigor, and a bloated religion, with all its bureaucratic rigidity, is so inadequate that it ultimately resembles myth more than an historically accurate picture. In its adolescent phase, mechanism not only did not strongly oppose religion, but drew copiously from it arguments in order to ideologically legitimize itself.

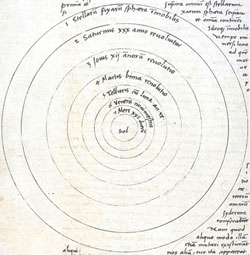

Copernicus (1473–1543) may have spoken of the “machine of the world,” but behind the mathematical and geometric proportions of the gears of this machine, he perceived divine order and divine providence. The advantages he saw in his heliocentric system were not empirical in nature—the geocentric system could predict with equal accuracy (given the observational instruments of the time) the motions of celestial bodies. However, the mathematical relationships were significantly simplified, which of course (he himself believed) suited the simplicity of divine order. Kepler (1571–1630) would follow a similar line of reasoning. God is again likened to a Creator (recalling Aquinas—in any case, the doctrine of creation is central to Christianity), who has constructed the world and infused it with His eternal principles. Only in Kepler’s case (in contrast to Aquinas), these eternal principles are not expressed in terms of Aristotelian teleology, but through mathematical equations and mechanical analogies; mathematics ceases to be a mental game and becomes the quintessential tool for understanding nature. Characteristic is Kepler’s saying: “The divine machine must be understood not as a creature, but as a clock”2.

The one who most explicitly placed mathematics as a necessary precondition for understanding nature was Galileo (1564–1642). For Galileo, however, mathematics was not merely a useful tool. The very reality of nature was, at its core, mathematical and quantitative. The only objective way to observe nature was through the primary qualities of things, such as their shape and size—in other words, through whatever could be mathematically expressed. Their secondary qualities (e.g., their color or smell) were merely subjective (and therefore uncertain) correlates of the primary ones. The next conclusion from this reasoning concerned humanity’s place in the universe. Since it is impossible to study humans exclusively in mathematical terms, they are perhaps nothing more than a bundle of secondary qualities not worth particular study. If Copernicus displaced Earth from the center of the universe, Galileo displaced humanity, relegating nature as the only field worthy of study. It is interesting, however, that Galileo does not yet refer to “laws of nature,” despite being very close to such a concept.

The final intrusion of law into nature would be carried out by Descartes (1596–1650). In the Principles of Philosophy3, he wrote unequivocally:

“The first law of nature: every thing, insofar as it depends on itself, always remains in the same state, and thus whatever is once in motion continues always to move.”

It is a “law” taught to every middle school student, which has now acquired the status of the obvious. However, it is not (and was not then) obvious at all! No direct sensory data confirms it, and in the 17th century it was naturally impossible to create laboratory conditions of absolute vacuum in order to test it. But Descartes had God on his side. Just as God is perfect and immutable, so the laws of nature must also be. Therefore, the motion of bodies cannot change without external intervention. For the mind of the 17th century, one more thorny question remained, which Descartes had to answer: if material bodies do not possess their own inherent forces (as Aristotle confirmed), then how is it possible for them to obey laws? For Aristotelian scholasticism, motion is also one of the possible ways of the body, just as a body has its own shape. A completely inert body without its own will certainly cannot either obey or violate rules. How are these transferred onto it? Descartes’ answer does not, of course, constitute a surprise. God, as the great lawgiver, simultaneously assumes the role of executive authority, continuously ensuring the eternal motion of bodies (a doctrine also called occasionalism).

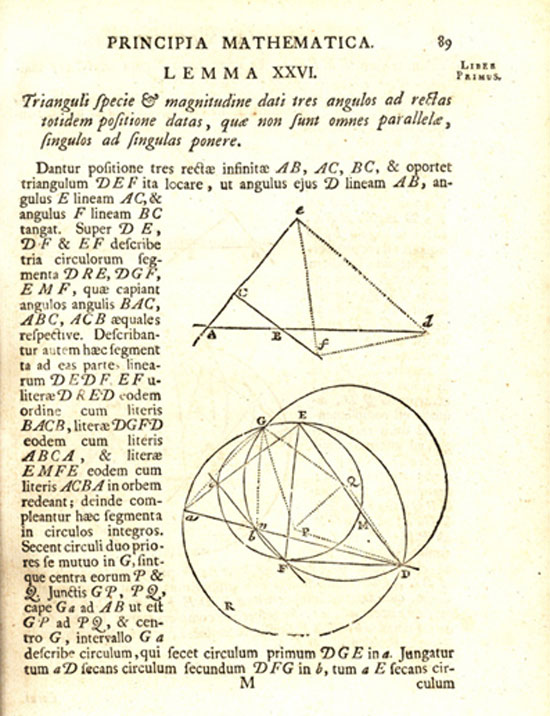

When Newton finally published the Principia Mathematica in 1687, he had no problem referring explicitly to laws of nature. The notion that nature obeys mathematical laws had by then become more widely accepted and had been more distinctly condensed into the doctrine of mechanism:

- All of nature consists of particles that follow the laws of motion (the idea of so-called corpuscularism).

- The world is contingent, which means that its laws, although expressed mathematically, cannot be discovered exclusively through logical deduction. Experimentation is also required. The omnipotence of God could have created a world with completely different laws. Only through experimentation can we discover what laws He breathed into the world – unless someone was willing to claim they had direct access to the will of God…

- God is omnipotent and governs the world directly, without intermediaries. Therefore, matter and the world have nothing sacred, they do not participate in God through hierarchies (as, for example, in Neoplatonism). God is the only sacred being who provides external order to nature.

- There is no difference whatsoever between natural and artificial, as, for example, in the distinction between natural and forced motion. In any case, the whole world is artificial as a creation of God. “All things are artificial, for Nature is the Art of God,” Thomas Browne, a 17th-century British intellectual, would say.

The relationship between mechanism and the new theology, which prioritized God’s omnipotence and His continuous, uninterrupted presence within nature, was extremely close. Mechanism only gradually managed to free itself from its theological “baggage” (which it did not initially perceive as such in its early stages). However, the notion that natural laws function within nature much like divine decrees remained firmly entrenched for nearly three centuries thereafter.

It would certainly be simplistic to assume that the transition from Aristotelianism to mechanism occurred for purely ideological reasons, as just another episode within the history of ideas, detached from broader socio-political developments. Without needing to place society in the role of the absolute cause and ideology in that of the causal factor, nevertheless the similarities and analogies are too obvious to be dismissed as mere coincidences. Starting from the renewed appreciation of mathematics as an absolutely crucial tool for understanding nature, it is not difficult to discern behind this epistemological reconfiguration its corresponding social elements. The practical utility of mathematics began to become increasingly significant from the moment the older aversion to engaging with practical matters started to fade. Faith in the importance of action, even at a purely technical level, was in turn not unrelated to the emergence of certain pioneering and proto-capitalist formations within Europe. A parallel development at the theological level naturally goes by the name of Protestantism and the renewed appreciation of work ethic that it brought about. The detached contemplation of the scholastics—and thus the use of mathematics for purely abstract purposes—now becomes something worthy of ridicule. If there is any indication of moral progress, it is more likely reflected in technical advancement.

However, even within mathematics, certain “paradigm shifts” are observed that are highly indicative of broader social changes. Just as Aristotelian space was distinguished by its different qualities, so too, according to the traditional conception inherited from the ancient world, numbers were not uniform; they too had their qualities. For example, zero was largely unknown, as it denoted non-existence, which, of course, cannot be measured. Similarly, the number one was not considered a number equivalent to all others, since it held the position of generator4. In a sense, it was the archetype of numbers, from which all others were generated. In any case, what is important is that numbers were not arranged on a single, linear scale so as to be directly comparable to one another. This would be the achievement of Descartes, who proceeded to a gesture of homogenization of numbers and, with the same move, managed to homogenize space as well (do you recall Cartesian coordinates?). Neither space nor numbers would henceforth have special qualities. The homogenization of space (and of the language spoken within that space) was, of course, one of the fundamental processes set in motion by the construction of nation-states in the early modern period. For a state to stand, it must have a unified space under its supervision in which it holds the monopoly of violence (and taxes) and a unified market, without strange exceptions and ad hoc local rules. It is difficult to avoid the conclusion that the extremely abstract conception of space in modern mathematics was the expression, at the epistemological and ontological level, of the process of formation of European nation-state structures.

Homogeneity, of course, is not achieved effortlessly. In order for the space to become level, continuous supervision and monitoring are required, as well as a central control mechanism. The fragmentation of power into multiple figures and separate regulatory frameworks, which was so common in feudal regimes (with local rulers and continuous concessions of special privileges), had to be replaced by a more “effective” administrative system. From this perspective, the absolute monarchies of the 17th century, which concentrated all powers in the person of a single ruler, were not necessarily backward regimes. On the contrary, they were precisely the catalyst needed by the nation-state to emerge from the mire of feudalism; not coincidentally, kings were among the strongest supporters of the “merit-based” staffing and bureaucratic reform of the state mechanism, in their effort to free themselves from the burden of the nobles. The king now becomes like a small God, a great legislator in whose domain the laws apply without exception and whose authority is unquestioned5. The image of nature following inviolable laws (of God) constitutes an almost faithful copy of the image of the modern state.

This remained the dominant image of nature for nearly 400 years, and has not yet completely faded (after all, we still live in capitalist states…). The first cracks in this legalistic and strictly deterministic conception of nature would appear only in the early 20th century with the emergence of quantum mechanics and, more specifically, its statistical interpretation. We will not go into details here. We will simply note that even the statistical uncertainties of quantum mechanics were not purely and solely a scientific matter. They drew their vitality from the broader intellectual anxieties of the era, with strong tendencies to reject “strict rationalism”6. Apart from being “anti-deterministic,” however, statistics is also the quintessential technical management of large numbers; hence, of large populations. It is therefore no coincidence that probabilistic conceptions of nature gain ground precisely at the historical moment when Western societies enter the phase of massification: mass production, mass consumption, mass democracy.

Those who consider all these strange epistemological anecdotes from the history of science to still seem very distant, should reconsider what world they live in. The theories of dynamic and chaotic systems that emerged after the war were yet another wave of fundamentally non-deterministic (in the traditional sense of the term) conceptions. However, even if these have little relation to current developments, genetics (especially that of large populations) and Big Data are at the forefront of the 4th industrial revolution, operating with exactly the same statistical logic. Interest no longer focuses on discovering solid and unchangeable laws, but rather on extracting statistical regularities that can be exploited for this or that purpose of biopolitical control7.

The exceptions (such as, for example, the side effects from some mass medical intervention, as a malicious person could say) and their justification take a back seat, once they are included in some probabilistic distribution and have been predicted by some cost function. Thus, if Galileo displaced man from the center of scientific interest four centuries ago, the statistical correlations of neural networks displace him once again; from the center of social interest, transforming him into statistical regularities and anomalies.

Tough luck!

Separatrix

- The historical data we present were drawn from the following sources. The book by E.A. Burtt, The Metaphysical Foundations of Modern Science (first edition in 1924), is one of the first attempts to investigate the origins of physical laws from a philosophical perspective.

In 1942, the Austrian Edgar Zilsel, under the auspices of the Institute of Social Research (of Horkheimer and Adorno) while it was located in New York, published his classic article The Genesis of the Concept of Physical Law. One would expect the bibliography to have been significantly enriched since then. This is not the case, however. A few more articles that have appeared sporadically are the following:

“The origin and development of the concept of ‘laws of nature’,” John R. Milton, 1981,

“The Origins of Scientific ‘Law’,” Jane E. Ruby, 1986,

“Metaphysics and the Origins of Modern Science: Descartes and the Importance of Laws of Nature,” John Henry, 2004,

“The development of the concept of laws of nature,” Peter Harrison, 2008. ↩︎ - The comparison with clocks is not innocent at all. The use of clocks and automata in general as ideological weapons was quite widespread at that time. See the documentary Mechanical Marvels Clockwork Dreams ↩︎

- See The Principles of Philosophy I&II, ed. Ekremes, trans. V. Gregoropoulou. ↩︎

- See Knowledge and Social Imagery, D. Bloor, The University of Chicago Press. ↩︎

- Of course, recalling Hobbes’ Leviathan. ↩︎

- See The crisis in Physics and the Weimar Republic, PEC, ed. Th. Arambatzis – K. Gavroglou. ↩︎

- We have made a relevant reference earlier. See the fourth example(;): the mechanical mediation of scientific thought, Cyborg, vol. 6. ↩︎