In the last decades of the 18th century and the first of the 19th century, the rising bourgeoisie constructed its own cosmology, its own reasons-for: for social relationships, for political organization, for public order, for bodies, for ages… The bourgeoisie was established through its theorems, and through them it began to reproduce not only its political but, even more so, its ideological hegemony in Western societies. The truths (within or outside quotation marks) of the bourgeoisie rejected those of the nobles, of the aristocracy, but also of the Christian church, considering them among others as corrupted, decadent, weak, declining. At various levels, through numerous occasions and via theories and practices, the bourgeoisie assumed social power as the shaping of vitality, health, and spiritual clarity.

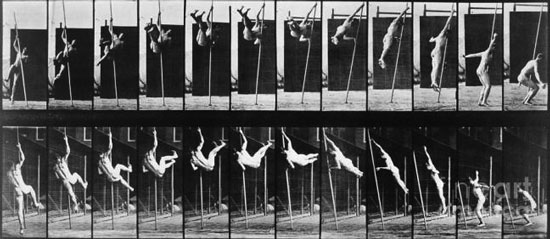

One of the crucial characteristics of urban fiction has been what we would call vigor. Vigor, vitality, strength: around these, the urbanites would formulate on the one hand the questioning of how they are acquired, and on the other hand the correct solutions to such problems. Until shortly before the 1960s, that is for more than 1.5 centuries, urban truths (within or outside quotation marks) would be established in countless fields of social relations. From the family to the conception of health and illness, and from the educational system to the disciplinary system and the administration of justice.

This gaze was not an abstract philosophical idea. The pursuit and conquest of it was the method (or, more accurately, the common practice and governing principle of a range of methods) for constructing social relationships. For example (by no means secondary!), the bourgeoisie cast down the divine eye/gaze from heaven, and while secularizing it as its own eye/gaze, it constructed both its own methods of surveillance (and self-surveillance) and the proper ways (from an aesthetic and moral point of view) for individuals to appear, for characters, for relationships between them. The bourgeoisie’s eye/gaze had some similarities (in terms of its capabilities) but also substantial differences from the eye/gaze of the sovereign. It was disposed to exercise a practical panopticism, equally regulatory as that of religion. But on the other hand, it was oriented toward discovering the particular truths of the world and things by penetrating as deeply as possible into their interior. The bourgeoisie’s eye/gaze was the quintessential instrument of the political, moral, emotional social body (in every manifestation – collective, familial, individual) that it constructed for itself: vision became the dominant sense (in relation to smell or touch, for example) in the bourgeois worldview, not through some ideological coup, but through the continuous, persistent, repetitive and diffuse “exercise of vision” across a range of issues. From moral self-surveillance, which as a secular variant of divine surveillance imposed the “look within yourself,” “search within yourself,” to the development of the specialized scientific eye/gaze. From the first line of gaze was born, and especially achieved, psychology and even more so psychoanalysis. From the second line was born the scientific obsession with the “search for truth” (of nature, of its “laws,” of bodies, of their capacity and/or incapacity) through the greatest possible and most systematic segmentation. The cutting and measurements, as the most reasonable supervisory procedures, through the gaze, into the “interior”, into the “depth of things”, The common typesetting of almost all sciences, from physics and chemistry to medicine, were made.

This is how bodies were constructed over the course of 1.5 centuries. What does “bodies were constructed” mean? Essentially, ideas about them were formed—ideas that became increasingly embodied, almost universally, in the Western/capitalist world: as moral codes or transgressions of morality; as aesthetics, tastes; as self-care or abandonment of the self; as constant self-monitoring and self-evaluation (of the body); as “uses” of the flesh or/and abuses; as sensations (or diagnoses by experts) of health and illness; as disciplinary methodologies (think, for example, what exactly the enforced sedentary posture for hours of study/learning meant within the educational system). For those who believe that human bodies are simply biological and that they have remained the same since we descended from the trees, the claim that both religion (with its punishments, its body/spirit dualism, its fasts…) and subsequently secular urban theory constructed and reconstructed bodies would seem arbitrary. But it is not. From cooking practices and theories about proper nutrition (within or outside quotation marks) to standards for male and/or female bodily beauty; from various forms of occupational strain and related illnesses to postures and appropriate behaviors under “formal” conditions; from awareness or ignorance of bodily disorders and definitions of health or illness to treatments; from the intensity and forms of sexual practices to types (and the “raw materials”) of intoxication; from appearance and fashion to the treatment of children and the elderly (and their bodies): all these and many more are not merely cultural determinants. They are co-constituents of embodiment.

Every human body (at least so far…) has the same organs. However, a body with scars (due to manual labor and indifference to wounds) is completely different from a gym body, or a body with silicone or Botox interventions. A female body after seven or ten pregnancies is different from a body that exercises motherhood without pregnancy (through a “surrogate uterus”). A body worn out in construction, fishing, or domestic work “ages” differently from a body worn out in the tertiary sector. A gym body has nothing in common with a rural body. Again: social, occupational, class, and cultural determinants are operators of embodiment.

So that we can say that the general social, ideological, and economic conditions work on bodies (and spirits, which are also bodily in one way or another) just as bodies (and spirits…) shape the conditions; or remain at the margins of mainstream formations. It is an unresolved dialectic, which allows us to say that we are not the kind that just came down from the trees, but an extremely distant descendant of it. A stranger.

The urban construction of bodies, relatively smooth over many generations, tolerant even of the drop-out exceptions of its children with artistic concerns, encountered its limit in an unexpected and unpredictable way, in the mass kinematic disputes of the ’60s and ’70s. The historical urban imaginary (in the western world always) for compactness and vitality was, to one degree or another, protestant. It meant and favored positive values through the restraint of desires; through the saving of vital forces; through the suspension of any waste. The disputes of the ’60s and ’70s, among other things, turned the table over – promoting a much more dynamic perception, always for compactness and vitality. It should no longer be conservation, restraint, suspension, rejection, self-limitation that should be the recipe of “health”, individual and/or collective – but the opposite. Inflation, waste, freedom, carelessness, eternal adolescence. If the shadowy model of the urban imaginary for bodies was (in specific ways recognizable) adulthood, for the dispute of the ’60s and ’70s it became adolescence; eternal adolescence.

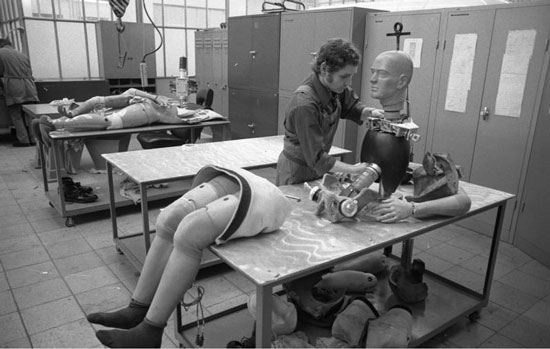

The dynamism of this entirely innovative (based on the history up to that point) approach stemmed from the belief that adolescence, in terms of vitality, is self-sustaining. Eternal youth, of course, could not be so; so much the better, then, for any elixir and any mediation of youth. Where urban ideology had established a certain (social, moral, emotional, epistemological) mechanics of bodies—a mechanics primarily of preservation—the final decades of the twentieth century witnessed a new mechanics: the mechanics of replacement (of the body’s worn-out components) or the mechanics of their enhancement. A little before cyborgs and “augmented reality” became subjects of special technical processing, there had been a social demand for them. – something that would hardly be recognized today as the immediate prehistory of the present.

And yet, a series of “data” from the end of the 20th and the beginning of the 21st century are products of a complex, visible and at the same time invisible process. Sexuality as the quintessential measure of vitality; the turn to eastern (religious) beliefs (and martial arts) and the emergence of a new dynamic asceticism; the sanitization of vitamins and (natural or chemical) “dietary supplements”; the expansion and psycho-emotional investment in drug culture; the apotheosis of the chemical industry of cosmetics and plastic (“corrective”) interventions: these are only some of the elements of this new social machinery for bodies.

The even more interesting aspect is that the search for the high-tech equipped body/spirit leaped directly from the controversies of the ’70s. If the “return to nature” was a neo-romantic rejection of urban industrial culture, there was another similar denial oriented towards the technological/cultural leap into the future. According to various declarations from the early ’80s, the bio-informational body would transcend many of the painful tensions of the historical urban world. Donna Haraway’s “A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology, and Socialist-Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century” is an emblematic text of this kind from the mid-’80s; and it will occupy us in the near future.

Ziggy Stardust