It is by no means necessary for someone to use a machine (from a smartphone to a robotic analyzer) to keep in mind how each wave of mechanization fits into the capitalist process. However, it is absolutely necessary for those who want to deconstruct, in a critical way, the capitalist “logic,” to understand how the various waves of mechanization are integrated into it. Without such understanding, much remains to be said, of course, about the technical basis (that is, the machines) of the bioinformatics paradigm. Yet most of it risks being phenomenologically unbearable, even fetishistic. And, unfortunately, this is exactly what happens: the new bioinformatics machines are considered “magical” or even “omnipotent,” by some liberating and by others demonic as such. But even intermediate positions are usually superficial and shallow.

The restoration of contemporary labor criticism is a difficult task, and certainly cannot be exhausted in one or two references. However, this journal aims to serve (also) this purpose. Therefore, we turn first to the sources of criticism of capitalist disorganization (here to Marx) where, paradoxically (;) and despite the idea of “obsolescence,” there are many exceptionally contemporary insights. And regarding machines, but not only.

The following concerns, as a first installment, what has remained in history as the fragment on machines [fragment on machines], from the Grundrisse1, which has constituted the basis for a large part of the theoretical analyses (and practices) of Italian autonomism. The “fragment on machines” is a few chapters of the Grundrisse, but quite large enough for us to republish it in full while commenting on it here. We will resort, for current needs, to individual sections that we consider important.

… As long as the means of labor remains a means of labor in the literal sense of the word, as it was directly incorporated, historically, by capital into its productive process, it undergoes only a formal transformation: for it now appears not merely in its material aspect as a means of labor, but also manifests itself as a specific mode of existence determined by capital’s overall process: as fixed capital. Integrated into capital’s productive process, the means of labor nevertheless undergoes various metamorphoses, with its latest form being the machine, or rather, an automatic system of machines (a system of machinery; the automatic is nothing but the most complete, more adequate form of machinery, and only this transforms machines into a system), which moves itself automatically, a motive force that is self-propelled; an automaton composed of numerous mechanical and intellectual organs, so that the workers themselves are determined only as conscious members of it.

In the machine, and even more so in machines as an automatic system, the means of labor is transformed with respect to its use value, that is, with respect to its material presence, with an existence sufficient for fixed capital and for capital in general; and the form in which it was incorporated as a direct means of labor in the productive process of capital is raised to a form placed by capital itself and corresponding to it.

The machine, from no point of view, appears as the means of labor of the individual worker. Its specific difference is in no way – as in the means of labor – to mediate the worker’s activity upon the object; on the contrary, this activity has been placed in a way that simply mediates the work of the machine, its action upon the raw material – supervising and protecting it from disturbances. Not like the tool, which the worker animates as an organ with his own skill and activity, and whose handling therefore depends on the worker’s dexterity. On the contrary, the machine, which instead of the worker possesses skill and power, is itself the artisan, having its own soul, the mechanical laws that operate within the machine; and for its uninterrupted self-motion, just as the worker consumes food, it consumes energy (coal, oil, etc.). The worker’s activity, limited to mere abstract activity, is determined and regulated in all respects by the movement of the machines – not the reverse. The science that compels the inanimate members of machines through their construction to function purposefully as an automatic mechanism does not exist in the worker’s consciousness; on the contrary, it acts through the machine as a foreign force upon the worker, as a force of the machine itself.

Notebook VI, 44, Volume B, page 531.

Here Marx makes an important distinction between tool and machine. Both can be used as means of labor. But the use of the tool depends exclusively on the skill and general abilities of the one who uses it. The machine, on the other hand, has its own “internal” capabilities, and what it requires is use in accordance with these “internal” capabilities. In this sense (Marx says or implies), while the tool belongs to the one who uses it, since it constitutes in some way an extension of his physical and intellectual abilities, the machine becomes (generally) part of capital; or, more correctly, the dominant form of capital, that which is called fixed capital.

Science now (and technology, we would add) which is the prerequisite for the construction and operation of every machine, does not constitute either necessary or sufficient knowledge for the one who operates a machine. It comes “from outside” in relation to him, and acts upon him as a foreign force.

Based on current data regarding new machines, someone hasty would raise two objections. First, that there are machines which do not belong to the employer but could be considered “personal”: personal computers or smartphones. And second, that there are machine operator specialties, such as programmers, who possess (must possess) scientific/technical knowledge related to the new machines.

The first objection is very superficial; essentially, it is wrong. Personal computers have increasingly less value (approaching zero) as discrete, separate machines. Their functional value lies in their networking. If one sees them as simply the “terminals” of a network (which could be the global network or a smaller, corporate one), then personal computers are merely the “controls” of a mega-machine. The cloud is already erasing the last remaining vestiges of “privacy” in personal computers. This is already true for smartphones: without networking, they are almost completely useless, or no more useful than notebooks.

The second objection is relatively (and only) correct. Even programmers have no knowledge of many aspects of the machines they program. Say, the physical hardware. While they are indeed specialized, they possess knowledge at the same formal level as a lathe operator in relation to the lathe machine: they can use it correctly, they can also develop some skills in its use, they can even repair certain malfunctions, but under no circumstances do they have the electromechanical knowledge required to build it.

Marx’s idea of an automatic system of machines, composed of numerous mechanical and intellectual organs, such that the workers themselves are determined only as conscious members of it, does not therefore constitute a “prophecy”—something that in his time existed only in seminal form. It is, rather, what he considered a capitalist tendency. And it is difficult to say that what Marx, over 1.5 centuries ago, understood as a tendency is not today almost a reality, if we conceive of the internet as a mega-machine (with owners): not only modern workers in many sectors but the entire body of its users are (we are) its “conscious members.”

…

Notebook VI, 44, Volume B, p. 532, 533.

The evolution of the means of labor into machines is not accidental for capital, but constitutes the historical transformation of the traditionally given means of labor into a form adequate for capital. The accumulation of knowledge and skill, of the general productive forces of the human mind, opposite the worker, was thus absorbed into capital, and appears as a property of capital; more specifically, of fixed capital, insofar as it enters the productive process as the means of production in itself. Thus, machines appear as the more adequate form of fixed capital, and fixed capital – insofar as capital is examined in relation to itself – as the more adequate form of capital in general.

…

Furthermore, insofar as machines develop – with the accumulation of social science, generally of productive power – general social labor is expressed not in labor, but in capital. The productive power of society is measured by fixed capital, exists in objective form within it; and conversely, the productive power of capital develops with this general progress, which capital appropriates free of charge. We are not here concerned with developing in detail the evolution of machines; but only from a general point of view; insofar as in fixed capital the means of labor, as regards its material side, loses its immediate form and confronts the worker materially as capital. In machines, knowledge appears as alien, external to the worker; and living labor appears subordinated to the objectified labor that possesses independent action. The worker appears as superfluous, insofar as his action is not determined by [capital’s] needs.

Notebook VII, 1, Volume B, page 533.

The full development of capital, therefore, only occurs from the moment when the means of labor is not merely formally determined as fixed capital, but has been realized in its immediate form, and fixed capital confronts labor directly within the productive process; yet the entire productive process is not subordinated to the immediate skill of the worker, but appears as the technological application of science. The tendency of capital is thus to give a scientific character to production, and direct labor is degraded to a mere synthetic element of this process. Just as in the transformation of value into capital, so also in the further development of capital, it becomes clearly evident that capital, on the one hand, presupposes a certain historically given development of the productive forces—including science—and on the other hand, drives and compels them to develop.

Here Marx notes two things. On the one hand, that the development of machines constitutes the development of a certain alienation of those who use them (the workers) in relation to their work (the “productive process”). And on the other hand, that this same development is due to the appropriation by the bosses of the “general social labor,” of knowledge and experiences that have been formatted as science. So that we can say that the initial alienation constitutes a capitalist-friendly opposition of “general social labor” (science/technology) to each worker separately. If we extend the position of the worker to the general figure of users of certain new machines outside the narrowly defined work, the alienation of each citizen separately (regardless of the type of education and specialization) arises in relation to general social labor and its creativity. This alienation, in turn, is the matrix of technofetishism, the idea namely (which many consider a more natural thing in the world) that new machines are “beings” with autonomous capabilities.

There is also something else that Marx points out, but does not analyze at this point in the Grundrisse: that it is capital (and its own necessities) that drives the productive forces/abilities into further, uninterrupted development. Among them science and technology (which for decades have almost merged, so we can speak of techno-sciences). What the fundamental capitalist necessity is for this endless development of techno-sciences emerges indirectly but clearly from the following excerpt:

…

The constant capital, in its determination as a means of production, in the more adequate form of machinery, produces value – that is, increases the value of the product – only from two aspects: 1) to the extent that it has value; that is, insofar as it is also a product of labor, a certain quantity of labor in objectified form; 2) to the extent that it increases the ratio of surplus labor to necessary labor, by increasing the productive power of labor and thus giving labor the ability to create in a shorter time a greater mass of products necessary for the maintenance of the living labor force.It is therefore absolute nonsense the bourgeois phraseology that the worker shares the product with the capitalist because the latter, with fixed capital (which moreover is also a product of labor, and constitutes nothing but alien labor that capital has simply appropriated), facilitates his labor (on the contrary – with the machine it deprives labor of all autonomy and all attractive character) or shortens his labor. On the contrary, capital uses the machine only to the extent that it allows the worker to work a greater part of his time for capital, to treat a greater part of his time as not his own, to work more for someone else. With this process the labor actually needed for the production of a certain object is reduced to a minimum, but only in order to utilize the maximum amount of labor for the production of the maximum number of such objects.

The first aspect is significant, because here capital – despite its will – reduces human labor, the expenditure of force, to a minimum. From this, liberated labor will benefit, and it constitutes the condition for its liberation.

Notebook VII, 1, Volume B, page 535.

…

Here Marx describes with exceptional clarity and simplicity the capitalist necessity that leads to the continuous development of techno-scientific capabilities and, above all, their formation into machines. The technical (mechanical) “ecosystem” reduces more and more the necessary labor time for one or another result; in their combination, machines and living labor reduce what Marx called socially necessary labor time. But thus, within given working hours (and even more so in their temporal extension…) an increasing amount of labor time “remains surplus” in production, time which is exclusively appropriated by the boss. Consequently, each wave of technological applications (machines) increases the surplus value that the boss can extract.

This sufficiently explains the unlimited hunt for technological innovations in general. There is, of course (Marx analyzes this elsewhere), also the opposite tendency. The use of new technologies (in place of older ones + labor) constitutes, in principle, an exit strategy for every employer. Which he avoids doing if (and only if) labor with the older machines is so cheap that what he loses in terms of productivity per unit of time he gains through the extension of time, intensification, and the low cost of the “labor commodity.”

In October 2013, during the three-day game over festival, among other topics, the digital proletariat, a workers’ investigation was also presented. One of the findings of that research, unexpected for general ideas about work and new technologies, was how low the salaries of people considered (and who are) highly specialized actually are. While, that is, one would expect programmers’ salaries to be multiples of unskilled workers’ wages, the reality is that they are usually only slightly higher; so that the expression “digital proletariat” is absolutely accurate. The above notes by Marx illuminate one of the two dimensions of this undervaluation.

Marx repeats below:

…

The capital itself is the moving contradiction: … it reduces the working time in the form of necessary labor in order to increase it in the form of surplus labor; hence, it places surplus labor increasingly more as a condition – a matter of life and death – for the necessary. On the one hand, therefore, it mobilizes all the forces of science and nature, as well as of social combination and social intercourse, to make the creation of wealth independent (relatively) of the labor time expended for it. On the other hand, it wants to confine these enormous social forces created in this way within the limits required for the preservation of the already created value as value. The productive forces and social relations – which are both different aspects of the development of the social individual – appear in capital simply and solely as means. And for capital, they are nothing but means, in order to continue producing upon its own narrow basis….A nation is truly rich when it works 6 instead of 12 hours…

Notebook VII, 3, B volume, p. 539.

the “iron man”

The cyborg, the synthesis of anything that could be considered a “living organism” (in a sense that, perhaps, goes down in history…) and cybernetic machines/technologies, is the fourth or fifth form in line that the adaptation (even the absorption) of the human by the mechanical has taken throughout the history of capitalism. Each such formation was ideologically grounded on the previous ones, even when this was not explicitly stated. Each such formation employed a universal rhetoric, on the one hand, about the allegedly inherent analogy between mechanical and human “functions,” and on the other, about the (bright) future of humanity thanks to machines. Each time, the bright ideological arguments, which among other things aimed to overcome reactions or even fears towards the “fearsome” machines, obscured the initial targeting, the initial purposiveness of their use.

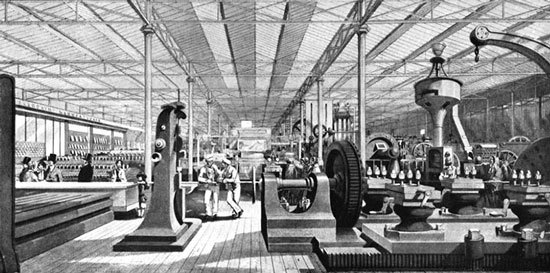

At the beginning of the 19th century, when the first wave of mechanization (through the establishment of the steam engine) had begun to spread to English textile mills, Andrew Ure, a professor at the University of Glasgow, became famous for publicly supporting the transfer of human thought to iron machines, in order to shape a self-propelled mechanism that would grow and learn. Ure, impressed by an automatic spinning machine built in 1824 by the engineer and inventor Richard Roberts, celebrated machines endowed with the thought, perception, and attention of an experienced craftsman. Ure named such machines, which he imagined would replace or discipline human labor in textile mills (and in the future in more and more fields), borrowing an ancient Greek word: androids… In Roberts’ spinning machine, Ure saw far more than just a device. He saw the coming “iron man”: the iron man, emerging from the hands of the modern Prometheus [Roberts], is a creation destined to restore smoothness and peace to the industrial classes and to make Great Britain a technological empire.

Not only for Ure but also for the growing number of supporters of the then “new technologies,” in the first half of the 19th century, self-moving machines appeared just as intelligent as the craftsmen they replaced. The distinction between human and mechanical was overcome; and, since machines were considered as living beings, it would be reasonable for humans to be considered living machines. It seemed that the idea of Descartes, who lived almost two centuries earlier, was finally becoming reality: Descartes believed that organic bodies are subject to the same physical laws as any other inorganic thing in nature. Of course, Descartes did not completely equate the mechanical with the living and the human: the difference, he argued, is the soul. Initially consistent with what would later be considered a detail, the industrialists of the 19th century could attribute all the main characteristics of human activity to essentially mechanical functions, which could be effectively shaped “without a soul.”

What proved beyond any doubt that the union of mechanical/artificial and human is not only desirable but also effective, was the ability (and that of the early 19th century) of artificial limbs for human bodies: wooden legs or iron hooks for arms. Especially wooden legs began to be used more and more due to the also frequent industrial accidents caused by the establishment of new machines, first in textile mills and later elsewhere. These early cyborgs (more correctly: machorgs) became the subject of a somewhat awkward but optimistic advocacy on behalf of Ure: the addition of tools in place of human hands… which is done to help the work of those who are disadvantaged by nature or have suffered some accident, as well as the addition of wooden legs, allows workers to do their job accurately, despite working with the disadvantage of losing a hand or foot.

The construction and use of increasingly efficient steam engines progressed alongside the development of a new (at the time) scientific branch of physics, thermodynamics. Thermal energy was about to become the equivalent of animal soul, and now the distinction between living beings and machines became insignificant. As it was formulated again and again, the human body and the factory machine are both engines that convert energy into work. As early as 1783, steam engine inventor James Watt had proposed the horsepower as a unit of measurement, the power of a horse; a unit that persists to this day in defiance of its ideological origin in dozens or hundreds of “horses” hidden in internal combustion engines.

The reformulation of the idea of man (essentially of the worker…) on the basis of machine specifications also changed the repertoire of discipline within factories. In the first phase, the problem was to make workers and laborers who were peasants—and had a “solar” and “seasonal” sense of time—submit to the clock and to the demand for continuous and intense/concentrated attention to machines. But with the analogy between human and mechanical, the problem of human productivity gradually began to be transformed into a problem of maintaining and better exploiting “human energy.” The issue began to take the form of seeking maximum performance, using the ratio of energy to work per unit of time as the criterion.

In this environment where machines on one hand simulated or replaced labor and on the other hand intensified or even exploited workers, Marx saw far more and more substantially than the idolatrous philosophy of technology or fear of it. Ure and the other industrialists saw in the spread of the first wave of mechanization what benefited them: the subordination, the attachment of human labor to the machine; the alienation of living labor from the machines. The integration occurred, in their view, both on a small scale (in each individual job) and overall: the factory became the general ideal of the machorg, the model of progress beneficial to employers.

Marx saw entirely different things in the same process. He saw a structural polarization between human labor and the machine, between living labor on the one hand and the mechanical expression, the mechanical “representation” of capital on the other. However, this contradiction/polarization would not be overcome through the destruction of the machine, through an inverted technofetishism that would confine human creativity to previous laborious forms. No. The contradiction/polarization could be overcome (this was Marx’s view) only if machines, understood once again as formations of social knowledge (: science, technique), were wrested from the ownership and jurisdiction of the bosses; if they entered the service of social creativity definitively and exclusively.

A more direct practical expression of this contradiction – Marx pointed out – concerns working time. With today’s data we could extend this expression to the general time of “engagement” with new machines and their uses, for work, for entertainment, for sociality, etc. For the mechanized factory of the 19th century the data were clear: the more this time is extended during which workers are the “conscious accessories” of machines, the more exploitation and alienation are intensified and deepened.

It is also significant, and here we will only hint at the issue, that the machorg (and even more so the contemporary cyborg) was not, in the industrial dreams of Ure and his contemporaries (and is not in today’s bioinformatic reality), an individual relationship or a set of individual human-machine relationships. It was the encoding of the general model of the desired capitalist reality, the universal fantasy for the world.

Marx saw in mechanization not simply an ontological modification or conflict, but a dynamic process of capital’s dominance over labor, which nevertheless included an increased capacity for liberation, not of the functioning of machines themselves, but of the (social) time and interest devoted to their use. If it concerns the master’s interest, then machines (with their intensive rhythms, with their operational demands, with their great productivity, with their metaphysics and fetishism) must be present everywhere, because they shape and effectively contribute to the continuous appropriation of creativity. If it concerns the workers’ interest (and, in an extended sense, the “social interest”), then truly and qualitatively liberated time is opposed to this appropriation.

For Marx, the machorg of his time (just like today’s cyborgs) were a knot that could not be untied technically. But only politically. Because it was political (in the sense of the political economy of capitalism) that was their root cause.

But, of course, what Marx did not see (because he could not) was that stage of capitalist development where certain machines would become such organic individual accessories that it would seem unthinkable that life still exists without them. The early cyborgs started as a restoration of some kind of disability, as a restoration of normal life. After several waves of technological applications and revisions on what is (or what should be) human, cyborgs are launched into the consolidation of an almost “divine” omnipotence.

Ziggy Stardust

- Grundrisse, Critique of Political Economy (basic lines of the critique of political economy). Written by Marx until 1858, but first published in 1939. All excerpts in this reference here are from the Greek edition of Grundrisse, from Stochastis editions. ↩︎