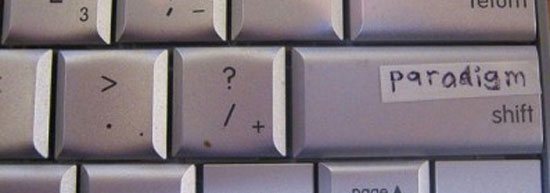

The words paradigm change are used sparingly but steadily in recent decades in international commentary (or babble) when it comes to commenting on some of the changes (sometimes real and sometimes hypothetical) in the life of postmodern capitalist societies. A common and at the same time comically tragic use of this term concerns various claims that capitalism… is no longer capitalism but something else (vague…). Other uses of the term concern environmental issues or the ideological hegemony of individualism—issues that are not insignificant, but which at best could be considered aspects of the evolving capitalist paradigm change over the past 3 decades at least; and not this change as a whole.

Before we proceed to the current notes, we owe a look at history. The term paradigm shift we owe to the American epistemologist Thomas S. Kuhn, and to his work The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, a 1962 work. “The Structure…” was a particularly innovative work in its time, a kind of “paradigm shift” in the theory and philosophy of the natural sciences, which influenced many in the following decades. Within his general position on how scientific models and truths of the natural sciences are overturned as new theories replace older ones, Kuhn placed the concept of paradigm shift at the center of his analyses. By the term Paradigm – and always speaking about the evolution of the natural sciences – he meant more than what would be called “dominant theory”. Certainly, some such “scientific theory” is always at the center of the corresponding Paradigm. However, this includes all the peripherals of scientific everyday life, from the beliefs and prejudices of the relevant scientists to the relationships and hierarchies between them or with their funders. This is the reason that, according to Kuhn and his followers, Paradigm Shifts in the natural sciences are neither predictable nor easily and effortlessly accomplished. Although every new scientific Paradigm appears with certain advantages compared to the older one that it will probably replace/overturn, it is never so complete, especially in the early stages of its formation, from a theoretical or/and observational-interpretive point of view, as to be irrefutable. It is therefore measured against the beliefs, routines, habits and interests of the supporters of the previous Paradigm.

The term, therefore, paradigm shift was coined in relation to radical changes in scientific/technical theories and not in relation to radical changes overall in the capitalist system. However, a few more words are worth mentioning about the origin of the term and the situations it referred to, because there are indeed some analogies between paradigm shifts in a component (albeit strategic) part of capitalism, such as scientific theories, and capitalism as a whole.

Here is how Kuhn’s position is briefly described by the editor of the Greek edition of “The Structure…” in the introduction to the work:

…

The accumulation of anomalies leads to a state of crisis. The scientific community loses confidence in the Paradigm and begins again to question the foundations of the field. A period of dispute begins where various Paradigms, new and old, coexist and oppose each other. It is the—usually brief—period of idiosyncratic science, which Kuhn describes using a distinctly political vocabulary. The Paradigm resembles a society in a revolutionary period; its theories and methodological mandates are institutions that fail to impose order; this is followed by a period of anarchy, where various social groups compete for power; critical argumentation progressively gives way to methods of mass persuasion; ultimately, power is gained not by the more correct program but by the more persuasive one. Similarly, at the level of Science, the crisis period is resolved by the dominance of a new Paradigm. However, this dominance typically does not result exclusively from the explanatory completeness of the new Paradigm; the dialogue among scientists begins to resemble a dialogue of the deaf, and their final choice resembles more a “religious conversion” or a sudden change in visual perspective, as in experiments in Gestalt psychology (Gestalt switches).

The dominance of a new Paradigm marks the completion of a scientific revolution. For Kuhn, therefore, scientific revolutions are those discontinuous developmental episodes during which “the beliefs of specialists change radically”… and an “older Paradigm is replaced, wholly or partially, by a new and incompatible Paradigm.” The scientific revolution leads to a reorganization of scientific communities, to the establishment of a new normal research tradition, to a new period of “calm,” etc.

What was considered particularly radical or “heretical” in Kuhn’s view is the way the crisis period is resolved, the nature of the scientific revolution. The change that occurs during a revolution cannot, according to Kuhn, be traced to a simple logical comparative assessment, a “reinterpretation of certain fixed and individual data.” Historical research shows that the introduction of a new Paradigm causes enormous communication problems among scientists. Scientists disagree about the scientific method, about the main current scientific problems, about the meaning of the terms they use (they speak different languages), and appear to live in different worlds. The Paradigms they embrace are incommensurable. Kuhn borrows this term from mathematics to emphasize that pre-revolutionary and post-revolutionary science is not merely incompatible but lacks even a common measure of comparison. Therefore, we cannot compare two different Paradigms on an objective basis, nor can we formulate evaluative judgments about the correctness of each. All we can do is understand each Paradigm within its conceptual and sociological framework and assess how consistent it is with its principles and effective in addressing the problems it sets out to solve.

…

We have to go to battle!

It is certainly interesting the political vocabulary that Kuhn used to describe what we would call a transitional period from one scientific paradigm to a completely different new one. Gramsci would say, speaking not about scientific transitional periods but about those of radical capitalist crises / restructurings, that:

The crisis consists precisely in the fact that the old is dying and the new cannot be born. In this interval, many different pathological symptoms appear.

However, the “entirely different” nature of each new paradigm should not be understood as its logical boundaries, whether it concerns a paradigm shift in the sciences or a paradigm shift in the capitalist organization of exploitation. Physics did not cease to be physics after the general acceptance of the theory of relativity or quantum theory. There are certain constants that held true before, and still hold true after. The experiment or the concept of proof is one of them. The same applies to a change in the capitalist paradigm: there are specific constants that apply both before and after. And this is easy to demonstrate: the change in the capitalist paradigm over the past 30 to 40 years (which is directly related to the crisis of the same period) is not the first to occur. It is the second. The previous one was the transition from the “first wave” of capitalist accumulation to the “second”: to the mass factory, mass consumption, the state-as-plan, etc. And again: …in the interim, many and various “pathological symptoms” emerged.

It would certainly be naive to argue in 1950 or 1960 that “this – is – not – capitalism” simply because “this” did not resemble the conditions of 1850 or 1860. Therefore, the search for and confirmation of “constants”—and not some postmodern relativism—of all things is the safe foundation that allows us to analyze a truly radical change in the capitalist paradigm, rather than indulging in empty talk about the “self-transcendence – of – capitalism,” as various shallow views about “immaterial” production, etc., imply.

the machine and the example

We attach particular importance to the mechanical infrastructure of capitalism, both during periods of “calm” in its operations and, even more so, during periods of paradigm change. We do not support any kind of technological determinism, according to which machines determine social relations, and that is all there is to it. In reality, machines themselves are also a product of social relations. Consequently, the relationship between mechanical infrastructure and social relations in any historical period is dialectical. Of course, the idea of the genius of the inventor, which seems to manifest itself independently (and sometimes even in opposition) to the dominant ideas of their era, always holds true. Such figures do exist and have existed across many different systems of social organization throughout human history. However, it is not the originality or genius of an invention, a machina as such, that generalizes and imposes the use of method A or B of technical construction, thereby altering, sometimes radically and subsequently, social relations. There are always constraints, criteria, possibly of social origin. Even more so in capitalist history, there are constraints and criteria of utility—criteria from the side of those who intend to exploit method A or B for their own benefit. Thus, there always exists a web of social relations (within which relations of power and relations of exploitation always take precedence) that functions as a filter in relation to ingenious inventions. Some will be rejected, never become widely known, never take their place in the epic of supposed progress—and such cases are numerous. Others will be adopted and, with or without rapid modifications and adaptations, will become established—subsequently altering, in a second phase, social relations.

Let whoever doubts the dialectical relationship between mechanical infrastructure and social relations in capitalism (and in paradigm shifts) consider the case of the steam engine and, subsequently, the internal combustion engine. In the last decades of the 18th century, when James Watt managed to finance the construction of his invention, he could generally predict its usefulness (based on the data of his time) and perhaps could also imagine some broader consequences of using steam engines. However, he could not have predicted either the industrial revolution brought about by the widespread use of steam engines, nor the birth of the proletariat, nor an entirely new era of intensified class struggle (in the 19th century) which were the results of the industrial revolution.

Something similar applies to the internal combustion engine. Obviously, it was invented to be used in small vehicles (and not only in trains or ships). However, which of its manufacturers could have predicted the ways in which the internal combustion engine would change the conduct of wars, global geopolitics, or the daily habits of an infinite number of car owners? In our view, it is safe to say: if the mechanical infrastructure of capitalism has particular significance, it is in its dialectical relationship with social relations. It is shaped by them and shapes them 1.

Radical paradigm shifts in capitalist history have been few. One was the “first industrial revolution.” The next was the “second industrial revolution,” in the first decades of the 20th century. The current one is the “biotechnological revolution,” and we can place its starting point, if not certainly its acceleration, in the last decade of the 20th century.

Because such radical changes do not happen abruptly, in a few weeks or months, but last many years, they may go unnoticed as such, even if their basic components are obvious. For example, what has been called mobile telephony started from portable wireless telephones and has already reached the stage of a universal remote control for everyday life. A handheld device that is about to be “completed” soon through its use not only in relation to other remote controls via the internet but also (via the internet of things) with the devices/machines of everyday life: refrigerators, washing machines, doors, cars, etc. All this has happened within just one generation, and has dramatically changed daily habits and customs. Smartphones are only one of the engines of paradigm change; however, few of their users are willing to analyze and realize exactly what this massive paradigm shift has achieved and foresees, in general.

If not already today, surely in a few years the overwhelming majority of the population will be certain that there was almost no life before the mobile phone. Civilized life. And that it is certainly impossible to exist anymore. It is not a matter of some kind of addiction that could be treated with psychotherapy. But a radical reshaping of social relations, ideas, behaviors. From the perception of time and patience to how one can cope with difficulty A or B “without a mobile,” and how one can help others in sudden difficulties, “without”…

One must distance oneself from the everyday nature of this radical restructuring in order to grasp its characteristics. Sometimes this distancing can occur within time itself; as if someone “absents” themselves for a while and then returns to see the changes accumulated.

In the first chapter of his fundamental book for understanding the previous paradigm shift, The Worker and the Timekeeper, Benjamin Coriat begins somewhat like this:

Ten years after he had given it up, a man returns to the path of the laboratory; work and the earth with its rhythms had kept him away for far too long. He straightens up as he prepares to face the recruitment office once again. Anxious, he wonders what could possibly remain of his “art”, of that patient climb, rung by rung, which had begun the day he was luckily hired as a “junior researcher” in a laboratory in Lyon.

His thoughts were full of self-confidence: “I had trust in my hands… a fantastic file weighed between my fingers… They would have me do a test… I had trust.” Despite the lack of certificates, with a bit of cunning, he managed to get hired. Natos enters, around 1920, the Citroen factory in Saint-Ouen:

“The entire space, from the floor to the ceiling of the shed, was cut up and organized by the movement of the machines. Crane bridges ran over the workbenches. On the ground, electric carts were crowded in narrow corridors. There was no room for smoke… In the depths of the shed, some enormous presses were cutting beams, hoods and car fenders, leaving sounds like explosions. Meanwhile, the hissing of the automatic hammers of the boiler room covered the deafening noise of the machines.”The discovery is unexpected. The factory, designed and operated in an “American” way, overturned the old order of things and unsettled people. The patient acquisition of “skill,” the feel of the handful, the movement of the fingers, that “sense of the file,” which until the early part of even the century allowed a worker to recognize his peers, is now obsolete. Time no longer consists of the stages of crafting the work. Now it must be gained ceaselessly. “We worked like those crazy films, with images succeeding each other at a stunning speed. We saved time. We lost it again waiting for the wheel, the milling machine, the crane bridge.” The second, the fraction of a second, now regulates successive movements. The stopwatch has penetrated into the workshop. Without doubt, we are facing the greatest revolution in the history of human production.

If someone “disappeared” even from a provincial society like the Greek one for thirty years, from 1985, and returned in 2015, they would be left speechless. People walking around muttering to themselves (but they’re not crazy, some device in their ear confirms it); people who risk getting lost in the streets if they don’t follow a device showing them the way; doctors who no longer know how to diagnose based on symptoms but instead scan various numbers and indicators, asking for even more numbers and indicators to be sure; vehicles that won’t move because some electronic component has short-circuited; offices where employees work and play alternately (but are paid less and less); millions of personal, individual self-exhibitions, self-presentations, and self-praises, regarded as private matters when they are something more than public; relationships mediated electronically and becoming increasingly impersonal, soulless, and stereotyped; bodies becoming ever more mysterious in their ailments and disabilities, falling with pleas into the hands of “specialists”… All these and more would make him feel that the customs he left behind in the mid-1980s are now obsolete. And they are. Without anyone being sure what truly needed to be overcome, discarded, or forgotten, and what not. And without anyone dealing with what (and who) opposes developments in a backward, selfish way, acting submissively.

The machines that shape the new configurable paradigm are of course not the milling machines and overhead cranes of the mass factory. They are not internal combustion engines nor radiological medical devices. In vitro fertilization, artificial limbs, and the great parade of DNA “decryption” are now considered commonplaces. Machines are everywhere, and are presented as increasingly “smart,” a characterization that would simply have been unthinkable for inanimate and technical objects, even just a few years ago. And this is not the end of the transition, which we will somehow manage to “digest.” It is rather earlier than halfway through.

It is possible that paradigm shifts within the narrow boundaries of communities of specialists, scientists and technicians may cause disturbances and conflicts that remain invisible to the “general public”, as Kuhn describes them. However, those general, universal paradigm shifts concerning capitalist societies and their organization as a whole are visible from everywhere. They concern all social subjects, who could (or could not) confront them critically, instead of adopting them blindly or rejecting them equally blindly.

In practice, what we are experiencing is what Gramsci described: the sickness of a prolonged transitional period. The sickness of the inability to grasp major changes, even when they unfold from (apparently) “small things.” The sickness of indifference to the unchecked directions these changes are already taking: electronic surveillance, for example, is massive and widespread. But this “is not the issue.” Ultimately, we live within the sickness of the disappearance of critique.

And as if that wasn’t enough, there is something even worse. The current paradigm shift (as with the previous one) is both nourished by and feeds into the current global “crisis.” This means that our own inadequacies, indifference, and resignations become multiple weapons in the hands of the world’s appropriators.

Ziggy Stardust

- This dialectic is one of the significant differences of capitalism in relation to previous models of social organization. In reality, the steam engine was a very old invention; certainly from Hero (of Alexandria) and, perhaps, in other parts of the world as well (e.g. China). However, the data (customs, traditions, beliefs…) of those societies did not allow the use of the steam engine for “productive” purposes. Something similar occurred with gunpowder; that is, its demarcation by social data. As is known, it is an old Chinese invention. However, the customs of that time in China forbade the confrontation of men (or armies) “from afar.” Consequently, while Chinese culture used gunpowder for fireworks (where it achieved impressive accomplishments…), Western Christian culture used it for firearms, with all that this implied for the conquest of the rest of the world. ↩︎