Common sense as a mechanism for representing and directly justifying the natural world, forms, people, things and social relations is an old issue, primarily in philosophy. Such a sense/perception of what is happening or exists around us is not at all timeless or absolute, it is socially and historically determined. It is based on the acceptance or rejection in a direct, almost intuitive way, of propositions which are evaluated as true or false / probable or improbable / possible or impossible. Common sense can concern anything: Daily habits and the description of forms, but also the laws of physics and the basic representations of matter and the universe. It can also concern (and this is what happens) the mapping and acceptance of social/class relations and correlations.

There are propositions that could undoubtedly be considered common sense, at least from a certain age onwards: the Earth is not flat; the sun rises and sets daily; a table can be used for food. Regular tooth brushing and the use of appropriate tools (toothbrush, toothpaste, sink, etc.) constitute common sense for someone who possesses these tools and adopts this daily habit. Yet even the association of this specific action with its means does not need to be clarified—it is implied—for someone who does not adopt this habit. It is enough that they live in a place where such things are sold. The existence of laws in a state also constitutes common sense. However, their content does not represent the same “common sense” for those who are subject to them. At some point, as the propositions/stances of common sense move beyond the natural world and begin to describe people and their societies, things start to become complicated…

A large part of what is referred to as common sense within societies reflects the dominant ideological/empirical/moral perception of how the world is (or how it should be). In this context, common sense includes both the perception of material reality through science and the metaphysical understanding of things in general.

That is why common sense, as a fundamental body of knowledge, has constituted a significant philosophical issue throughout the centuries. Both as a technique of power and (less frequently) as a challenge to this technique. The treatment of knowledge, even in its “common sense” version, as a separate philosophical issue is problematic. And this is because knowledge and its intensive accumulation, its codifications and representations in new machines, the evaluation of its usefulness (by whom and for whom?), the ownership of the means of its production and circulation, and our relationships with them are fundamentally political issues.

Common sense in new machines

In metamodern capitalism, the acquisition and transmission of knowledge about the world is increasingly mediated by new informational and networked machines. Common logic, as a set of perceptions and knowledge about the world, thus acquires a new distinct dimension – techno-scientific – as one of the, still unresolved, issues of artificial intelligence concerning the behavioral anthropomorphism of new machines.

Nine years after the publication of Turing1, with the famous question “Can machines think?” and the invention of what subsequently became known as the Turing test, John McCarthy2, in 1959, posed the problem of the lack of common sense in machines in a publication titled “Programs with Common Sense.” The subject of this publication was a program that would be able to generate advice (The advice taker), theoretically for anything, based on logical representations of common sense:

“Interesting work is being done on computer programming so that computers can solve problems that require a high degree of intelligence from humans. However, certain elementary verbal reasoning processes, so easy that they can be performed by any healthy-minded person, cannot yet be simulated by machine programs…

… A program has common sense if it can automatically infer from itself a sufficiently large category of direct consequences from whatever it is told in relation to what it already knows…”

Several decades later, in 2004, Marvin Minsky3, founder of the MIT Artificial Intelligence Laboratory and a prominent figure in the field of “Common Sense Computing,” published together with his collaborators:

“Computing devices have become essential in modern life, but they remain largely ignorant about the people they serve and the world they penetrate so deeply.

[…] Over the years, many complex problems have been largely solved, from programs that play chess to business management and design, but typically these solutions use heuristic methods and representations developed by the programmer and are functional only in some specific field of application. When circumstances differ from the predetermined parameters of their representations, programs are unable to generate new heuristic methods or modify existing logic to achieve their goals. The failure of the field of artificial intelligence to make significant progress toward human-level intelligence is the result of emphasis placed on problems confined to specific domains and specific mathematical techniques.”

These two texts have a time span of 45 years, yet their expectations remain the same. The new machines under design should possess processes that, through special representations, will be able to simulate human common sense.

Perhaps at this point, 56 whole years after the first publication and since no relevant (technological) revolution of common sense has occurred to this day, we could celebrate the difficulty of these efforts. We could defend knowledge in general and common sense specifically (even if we are critics of various manifestations of it) and declare that the greatness of humanity cannot fit into machines. In this way, we would most likely end up with a pending issue between the metaphysics of new machines and the metaphysics regarding the superiority of the human mind. Instead of concluding our topic in such a way, we will attempt to explore the ways in which “elementary knowledge” is sought to be represented, the purposes of pursuing such anthropomorphism in new machines, and the consequences arising from these applications of representations in the interaction between human labor (living labor) and machines (dead labor).

Knowledge Bases and Algorithms

Parallel to the representations and simulations of neuroscience regarding the functioning of the human brain, for more than fifty years now, another race is underway to incorporate as much knowledge as possible into the operation of new machines as manageable, exploitable data.

The process of importing human common sense into new machines involves two basic aspects. On one hand, the recording in special logical languages of elementary knowledge propositions with the goal of creating knowledge bases. On the other hand, the processes-algorithms that make possible the combinational exploitation of the data of the knowledge base so that “valid” common sense reasoning/conclusions are produced as the machine’s output, depending on the working hypothesis under examination.

According to a review4 of progress regarding the linguistic formalism capabilities required for machines to be able to produce common-sense reasoning, the key issues that appear to concern technoscientists and are referred to as “difficult” in their approach are summarized in the following four points:

1) The development of a formal language that will be sufficiently powerful and expressive.

2) The acquisition of millions of facts/data that people know and based on which they can make logical inferences.

3) The correct encoding of this information into logical sentences.

4) The construction of a system that will be able to use this knowledge efficiently.

The knowledge base of data and its massive recording presupposes the linguification of anything that can be considered an expression of common logic, not directly in the machine’s algorithmic programming language, but initially using a formal language of logic.

The efficient, if possible in real time, combinatorial utilization of the recorded data presupposes the application of algorithms that will use the underlying knowledge records by selecting from the set of recorded expressions those that match the current discussion – exchange of “reasoning”. The relationship of the specific knowledge base with the algorithms is what will determine the outcome.

The twin database – algorithm, using special logic languages as glue between them, is the dominant scheme for mechanizing common logic. Alternatively, using the terms of neuroscience, the brain where any expression of logic occurs can be represented as a storage space (memory / knowledge base), but also as complex processes of algorithmic handling and selective data transmission (neurons). The representations of neuroscientists and artificial intelligence specialists converge, although the tools seem to be different. Except perhaps for one that is common: the encoding / linguification of anything that falls under their prism, as a connecting link with the new information machines.5

Despite the difficulties of such a mega-project of constructing and utilizing knowledge bases, there are already several multi-year efforts recorded by universities, companies and government (mainly military) services in direct interdependence regarding their development.

Catherine Havasi is a founding member of such a project at MIT called Open Mind Common Sense. In a relatively recent article, she informs us about some of these efforts:

“You may have heard of Watson, famous for his victory on Jeopardy6, but what is less known is that his predecessor was a project named Cyc, developed since 1984 by Doug Lenat. The creators of Cyc, under the name Cycorp, manage a large repository of common sense facts expressed in logical linguistic expressions. It remains active to this day and is still one of the largest common sense projects based on logical linguistic expressions.

http://techcrunch.com/2014/08/09/guide-to-common-sense-reasoning-whos-doing-it-and-why-it-matters/

The Open Mind Common Sense project began in 1999 by Marvin Minsky, Push Singh and myself. OMCS and ConceptNet, its most well-known offshoot, include a database of information in plain text as well as a large knowledge graph. The project evolved with early success through crowdsourcing, and now ConceptNet contains 17 million facts across many languages.”

The Cyc project appears on the internet as a more closed, corporate project, while its open source version is considerably more limited compared to the original platform. Publications regarding its operation and applications are also few. Among these, an application for a knowledge base recording terrorist organizations7 stands out. The ambition of this project is for its knowledge base to serve as a substrate for “smart” applications.

Regarding the MIT’s ConceptNet project, since it is open-source and crowd-sourced, we couldn’t resist the temptation to visit its main page.

The way one can input data into the knowledge base is by registering associations between words/concepts using predefined connecting phrases. The encoded phrase is interpreted and produces a “common sense” sentence with the following form:

termA – link – termB: “A common sense sentence that relates the terms in natural language”.

Each term is underlined as it constitutes a link to a new page with correlations related to it.

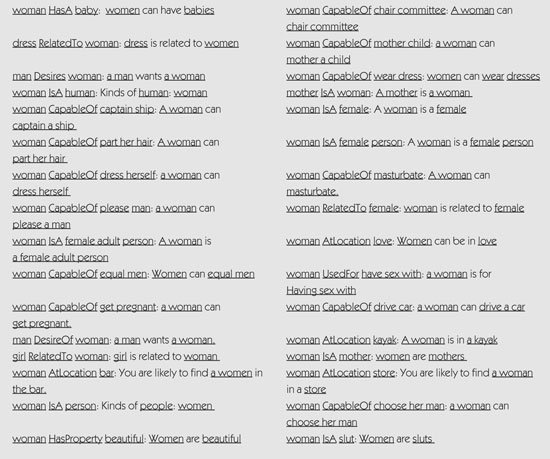

What are the data that the public can enter as common sense for the term “woman”;

In the following table, the results of this search are shown.

Address: http://conceptnet5.media.mit.edu/

Search for a concept… Woman

Output of the knowledge base (the first 34 results):

Many clichés and pointless observations, considerably more stereotypes and sexism – and in the end brutal sexism. It is indeed common sense, without a doubt!

Isn’t it ultimately the case that the quality of these recordings is a matter of correlations, and if we all become together—us and you, the thousands of readers of cyborg (!), contributors (part of the crowd, a thing)—we could give a different note to the machine’s common sense? The irony, of course, refers to the postmodern participatory attractiveness of the medium, which could even include such illusions of alternation8.

Human-machine interaction

If one consults the relevant literature on our topic, they will find that the ultimate goal of integrating human common sense into machines is Artificial General Intelligence (AGI). What we initially referred to as the behavioral anthropomorphism of machines concerns not only their external appearance but—what interests us here—their ability to engage in dialogue. That is, to produce reasoning and express conclusions in a way that does not differ from what is defined as human behavior. In 1968, the movie “2001: A Space Odyssey” portrayed such machines as existing by 2001, within the realm of science fiction. Today, this temporal milestone is projected for the middle of the century, around 2050, by scientists and experts. However, any expectations and visions regarding artificial intelligence, when grounded in reality, can only pertain to the human-machine interaction as a relationship. A relationship that tends to become universal, both in modern forms of work in the tertiary sector and more broadly, in increasingly expanded segments of social space and time.

Within this framework, one might wonder: What could be the relationship of the historically and socially determined “common sense,” in the non-virtual world, with its reflection in cyberspace? Is it a simple reflection, as if one were writing it in a book, a newspaper, a magazine? Or, ultimately, does its incorporation into new machines not serve the same purposes as “traditional” common sense—is it, in other words, beyond all logic?

We will attempt to explore such questions, starting from what we already know as human-machine interaction and the intense transformations it already brings to work and life.

When using networked information machines, computers of all kinds and the Internet, the interactive relationship between their operator and them is not directly obvious as such a relationship (operator-machine).

What if the basic input devices of these machines, the keyboard, the mouse and the touch screen, are at least “primitive” compared to the visions for new artificial intelligence systems? Even with this “old”, manual way, the user experience of these machines, after a period of familiarization (e.g. one month in office work), shows that both the operator’s perception of space and time and his “behavior” are substantially altered, corresponding to certain thoughts-actions that must be repeated during this interaction.

For a relatively experienced user, the correspondence between thought and action tends to become identification. In other words, external behavior towards the machine (typing, mouse movements, clicks, caresses and hits on the screen, as well as body posture, various ticks, etc.) increasingly matches the thoughts-that-are-translated-into-action, those that can be perceived by the machine. Behavior, thoughts and actions in this way are subsumed as a unified whole under the machine’s specifications. However, the most important thing is that this – often violent for the neck, hands and especially the mind – “dialogue”, this interaction, is mainly perceived as a purely human activity/state and not as a result of the human-machine relationship.

The machine, apart from being a (trans)porter of the knowledge that someone will bring/deliver—such as someone surfing the internet, for example, searching or entering information—becomes also a permanent, persistent transmitter of knowledge about what the machine itself is and what it can do, about how it operates. The common sense/perception of the worker/operator of this machine is precisely the illusion that this machine can produce and reproduce not only the image of mechanized knowledge and its own “self,” but also the dominant, self-evident image/perception of the human labor that is performed during its use. The identification of the image/perception of dead labor (of the machine) with the image/perception of living (human) labor has already become a given “common sense” fact in the real world, which could be encoded in the phrase: machines tend to acquire human characteristics. And conversely: The human mind is nothing but a very complex computer.

We present here an excerpt from a scientific publication titled “Usable AI requires common sense knowledge”. This is a simplistic scenario of using knowledge bases / common sense algorithms to build smarter user interfaces for machine interaction:

“At any given moment, the user interface has a vast variety of options for how to respond to user input. Usually, interface designers simply choose one of these options, more or less arbitrarily. Wouldn’t it be better if they could assess the situation and suggest a reasonable, if not the correct alternative? Common sense can therefore be used to provide intelligent defaults.

When a user asks to open a file, for example, which one out of all of them? Modern systems simply open the last folder that was used, etc. What would happen if the computer had even a little understanding of the work being performed and could suggest relevant files? Or if I could say ‘transfer the files I need for my trip to my laptop,’ and it would bring my travel reservations, maps, my slides, etc., without needing to name each file individually?”

A desirable form of machine input in the scenario described above would be speech, language. The “voice assistants” of mobile phones are moving precisely in this direction9. Perhaps, in a more advanced futuristic version, the input could be thought itself, wirelessly via wireless implants or wired via electrodes. The mechanization of “common sense” in combination with the mechanization of language10, but also in combination with neuroscience and the mechanization/representation of mental states and processes, show the way toward these directions. However, does something change with the use of these “innovations,” regarding what we describe above as “subordinating humans to machine specifications” and “ideological identification of human labor with mechanical labor”? The core of the functions performed by the machine, whether it “understands” words or “reads” thoughts, actually consists of sequences of algorithmic processes.

Even if we discard the keyboard, mouse and touch screens as input devices, the identification/subsumption relationship remains. It may even be intensified, given that the representations of “common sense” within networked information machines concern, in a way, the world outside them11. For what purpose? The most “abstract” possible human input that will produce the optimal mechanical output is pursued with specific intent: any mechanized representations of knowledge are deployed to increase the efficiency and intellectual intensity of already mechanized (ideologically and practically) human labor. It is precisely this tendency/intent that intensifies the transformation of labor. This transformation dictates that the human element (living labor) must be moved closer and deeper into the mechanical, as they interact; and not the reverse. And as this transformation intensifies, it will become easier to mechanize the human element than to “humanize” the mechanical.

If all these are true, then any defense of the human, social, or animal element could not simply be based on the inability of contemporary artificial intelligence machines to represent/replicate/falsify certain characteristics of it. The techniques exist and will continue to evolve and be applied more and more intensively, in more and more fields. The accumulation and representations of knowledge—in general—and of “common sense”—in particular—are such techniques. Their “truth” and their power lie precisely at the heart of the alienated relationship of the worker/operator to the means of production.

Ultimately, efforts to add a dimension of “common sense” to new machines fundamentally mean the accumulation and integration of human knowledge and experiences. Once these are first simplified into brief sentences, understandable by both humans and machines, they can constitute the artificial implementation of a human-machine understanding of the world, in an endless interaction within cyberspace. But in this case, the only common sense that seems to be shaped in the real world is a kind of postmodern, monolithic condition where any (whatever) highly complex tool can be transformed into a general, universal mediator of life.

Rorre Margorp

- In 1950, A. Turing’s publication “Computing Machinery and Intelligence” appeared in the journal Mind (#49). ↩︎

- The coinage of the term “Artificial Intelligence” is attributed to John McCarthy. He is considered a key figure in the establishment of the scientific field of artificial intelligence. ↩︎

- Marvin Minsky is known for his contribution to various scientific fields including artificial intelligence, cognitive psychology, mathematics, computational linguistics, robotics and vision. His main work regarding the perception of the structure of human intelligence and its functions, within the framework of his work on the mechanization of common sense, is presented in two of his books: “The emotion machine” and “The Society of Mind”. ↩︎

- This review was published in 2004, under the title “Introduction: Progress in formal commonsense reasoning”, in a special issue of the journal Artificial Intelligence (#153) on the topic of common sense and logical formalisms. ↩︎

- For more on the representations of neuroscience: Cyborg #3, Are consciousness and memory techno-scientific “objects”? ↩︎

- For a related overview: Sarajevo #49, dear Watson: the dying greet you. ↩︎

- This application is titled Terrorism Knowledge Base (TKB) and was implemented on behalf of the Air Force Research Laboratory of the USA. If you wonder what the relationship of common sense is with the “war on terror”, we have no ready answer. ↩︎

- The question of another (alternative,颠覆性的, or whatever you want to call it) mechanized common logic will not concern us further. After all, apart from the registers of the above records, there could also be more “progressive” ones, in the present or in the future. In any case, there are techniques that can filter the output of any search engine, using the content of each recipient’s emails and previous searches. The already existing software of companies, such as Microsoft, Apple, and Google, could ensure that only data matching each user’s profile is displayed. As for the source of the records, the Internet itself might prove to be better raw material for extracting polymorphic correlations from any human registers. ↩︎

- Cyborg #1: speak… in the voice of the machine. ↩︎

- For more on this topic: GAME OVER 2014 Festival, Presentation: Language and New Machines _ Mechanization of Language. ↩︎

- With an asterisk: as the ratio of hours outside the machine’s usage to hours within it becomes smaller, perhaps these representations of the “old,” offline world may cease to be so significant. ↩︎