Man becomes, in a way, the sexual organ of the world of machines, like the bee in the plant world, allowing it to reproduce and develop new forms. The mechanical world responds to man’s love by satisfying his desires, providing him with wealth.

Marshall McLuhan, 1964

People are the sexual organs of technology.

Kevin Kelly, first editor-in-chief of Wired, 2007

Welcome to the Future, one of our favorite childhood pastimes. We like to toy with it, as our numerous utopias and dystopias testify. And just like with “life after death,” everyone imagines it however they please, since no one has been there… Many of the proposed versions of the future include robots. The present also has robots, but in the Future it is said there will be many more. Is this good or bad? We haven’t decided yet…

Today, industry systematically uses robots, worshiping their advantages: they never get tired, they don’t need pension programs, nor do they go on strike. However, this trend causes a specific anxiety: what will happen to the consumer base if robots replace all human workers? Who will buy all these things that robots will make so cheaply and endlessly? Even the seemingly harmless uses of robots may have their disadvantages.

Nevertheless, we continue to push the boundaries; this too is a consequence of our clever brain. Hephaestus had constructed artificial assistants, but he couldn’t resist and made them in the form of stunning golden maidservants, a bevy of enchanting girls just for himself. Pygmalion carved a female statue out of ivory and then fell in love with it. We excel in this direction: the movie “The Stepford Wives” serves as a beacon, and in the recent film “Her,” the protagonist is captivated by the compassionate yet artificial voice of his phone’s operating system…

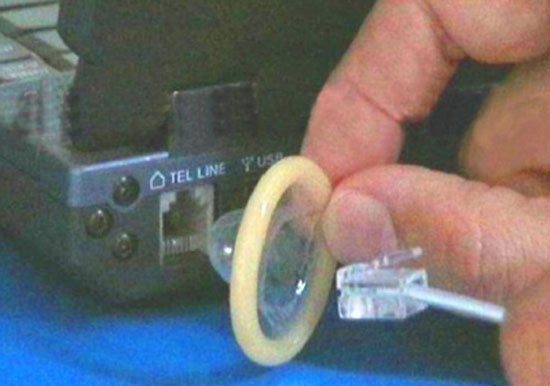

Even further, almost at the limits, there are people today who dream of robotic prostitutes, complete with self-cleaning hygiene systems. If the prospect of getting stuck painfully due to some malfunction keeps you from trying a prostibot with a full body, you could try a remote kissing device that delivers the sensation of your loved one’s kiss to your lips, through tactile feedback and the appropriate egg-like equipment (as long as you close your eyes). Or you can wander into the emerging world of “teledildonics” – that is, remotely controlled vibrators. Pull the levers of the gaming machine and watch the results on the screen. No germs! Wait for Google or Skype to include something like this…

Can sex on demand change human relationships? Will it change human nature? What is human nature, anyway? This is a question that robots—both real and fictional—press us to think about.

This excerpt is from a New York Times editorial (December 2014) titled Are Humans Necessary? by Margaret Atwood1. The article was prompted by the launch of the SPARC program, a partnership between the E.U. and 180 companies and institutions, aimed at maintaining and strengthening Europe’s leading position in the global robotics market. At the same time in South Korea, the government has set a goal for every household to possess a domestic robot by 2020 – in the role of a servant, with a clause prohibiting sexual contact – while the American Pentagon has signed an agreement with RealDoll, a company that manufactures sexbots, for the supply of modified robots, in order to familiarize soldiers with providing first aid on the battlefield (and why not, perhaps for organizing robotic joy divisions).

The future may well be open, as Atwood claims, but it will certainly overflow with excessive libidinal energy, as the new technologies and the new biocomputing paradigm already demonstrate. It’s not just the internet, which essentially exists for the distribution of pornographic/erotic material, as statistics show and critics have boldly declared in a timely manner; at the same time, a prolific and motley universe of companies, inventors, artists, scientists, futurologists, and charlatans has set out to decisively intervene in sexuality, in relationships between living beings and between living beings and machines, with the body and its mutations as raw material. This activity, which ranges from the simple production of sexual content through digital media to biohacking, robots as sexual “companions,” and cyborg-sex, is so noisy as to ultimately eclipse both the stakes and the historicity of the subject—the Spectacle never lacked explicit purposes! Because the relationship between technology and sexuality is neither new nor has it ever narrowly concerned “pleasure,” nor aimed solely at “liberating the imagination” and the body from the narrow confines of conventional and conformist sexual relationships. In order to demonstrate this relationship, before we return to the present, we will attempt a historical overview, though not in the realms of theory, science, or its applications, but focusing more on literature, the visual arts, and cinema. And this is because such creations, in certain cases, represent and reveal in a more emphatic way what is a diffuse general social condition.

Sexuality and technology: the genealogy of an unusual relationship

Although the concept of the cyborg is relatively modern, the hybridization of human and machine is not recent, at least as an artistic invention, pursuit, and avant-garde experimentation. The relevant philology was already inaugurated in 1748 when the work L’homme Machine (Man Machine) by the Frenchman Offray de La Mettrie was published, where the human organism is interpreted using the model of the clock mechanism. The 17th and 18th centuries were full of automata, anthropomorphic devices showcasing technological capabilities and intricate mechanical toys, which constituted the prototypes of the first machines of the industrial revolution and inaugurated the imagery of the robot and the cyborg. It is not coincidental that the body that stars in most automata, the body that is mechanized and paraded festively as a fusion of technology and biology, is the female body. From then until today, the same myth is continually implied: that of constructing the perfect female automaton/robot/cyborg who will fulfill the “feminine virtues” of unparalleled beauty, complete devotion, and absolute submission; the bio-mechanical female device that will flawlessly fulfill both roles, that of the servant and the beloved. At least in those early biotechnological phantoms, what is now carefully concealed was glaringly obvious: that the intersection of body and machine traps and confines the body, since it presupposes its suffocating restriction and brutal transformation; the machine subjugates the body, it does not liberate it.

Later, when Mary Shelley was writing Frankenstein or The Modern Prometheus (1818), she had in mind not merely a dark Gothic horror story, but—among other things—a commentary on modernity and the unprecedented expansion of industry that had marked her era. Shelley’s novella is an impressive and early testimony of techno-eroticism, as the entire story unfolds around the triad of sexuality-technology-fear. From the “birth” of the monster through “unnatural” scientific methods, to the fear that the monster might ultimately reproduce itself beyond the control of its maker / “father.” The monster, this stitching together of limbs from dead bodies which is nonetheless activated and acquires consciousness and will thanks to technology, causes horror not only through its repulsive appearance, but also through the sexuality it emits: Frankenstein is terrified when the monster expresses the desire to find a “mate”; the crowd is attracted but ultimately frightened when the monster attempts to become “desirable.” The erotic desire on the part of the anthropomorphic artificial being appears here as unacceptable; yet, not an unthinkable possibility.

During the 19th century, references to sexuality had already been significantly technologized; expressions such as “release of pressure” or “safety valve” were common terms relating to desires and sexual practices, drawn from the functioning of machines. The literature of that era had begun systematically to imbue technology with particularly sexual characteristics, often combining them with violence. When Freud sought a metaphor to describe what he believed was the ego’s control over the id and libido, the most suitable one he found was that of the steam engine. The relationship of technology and sexuality, moreover combined with fear and violence, is by no means contemporary. Furthermore, the history of this relationship is revealing at many points about the entire modern spectrum of practices, pursuits, and fantasies that we code under the term cyborg-sex.

Revolution, absolutism and sex-cyborgs

How did cyborgs contribute to the consolidation of Nazi power? And how is cyborg-sexuality connected to totalitarianism? Such questions certainly seem alien if examined within the narrow framework of modern discourse on bio-technological bodily mutation, but the answers are directly relevant, on one hand, to the historical trajectory through which technology has been invested with sexual attributes, and on the other, to the hidden (even from its own proponents!) outcomes of contemporary techno-fetishism in relation to sexuality. For the cyborg—as a hybrid of machine and human, and not strictly in the sense of a cybernetic mechanism—is not for the first time in our era that it conjures up both individual and collective fantasies. This representation of the “new man” as a synthesis of organic and technological elements had appeared in the past, playing a significant role in the culture of the Weimar Republic2. To some extent, that Weimar creature we might call the proto-cyborg was an indication of a frightened response to the enormous destruction caused by the First World War—the first mechanized military conflict in Europe—but at the same time, it was the figure upon which much of the artistic and political avant-garde projected either its utopian hopes or its dystopian anxieties. Three moments in the history of this figure deserve attention. The first is the appearance of a kind of cyborg in the work of the left-wing Berlin Dadaist Raoul Hausmann in 1920. The second is in 1926, when the cyborg appears in a leading role in Metropolis, Fritz Lang’s ambiguous yet essentially reactionary film. The third is in 1933, when the cyborg emerges as a central element in the work The Worker by the right-wing radical Ernst Jünger, a work propagandizing for totalitarianism and technological modernity. To prevent misunderstandings, let us clarify that there is no equivalent term for “cyborg” in the German language—not today, let alone during the interwar period. Moreover, referring to cyborgs during the interwar era, as far as we know, constitutes an anachronism (justified, as we will explain). The concept itself emerged only after the formation of cybernetics, and various unsubstantiated sophistications that uncritically extend it into the past are merely cheap attempts to legitimize it in the present. But if we keep in mind that the cyborg is simultaneously a real and conceptual construct, a creature of both imagination and reality (and experimentation in between), then we are fully justified, as will become clear, in claiming that the cyborg did indeed exist as a conception, in a preliminary form, in interwar Germany—if not in language or scientific activity, certainly in artistic production and socio-political critique. So, while the cyborg may be a 1960s invention, its conceptualization did not occur in a vacuum; it has historical roots not only in science and technology but also in philosophy, politics, art, and mass culture—it is precisely these roots that we examine.

During its short lifespan, Weimar was a laboratory of intense social, political and artistic processes. One of the movements that stood out was Dadaism3, which exerted influence even on the conservative establishment. Among the most significant representatives of the Berlin scene and a member of the most anarchic tendency of the movement was Raoul Hausmann, who was inspired to create a figure that evokes the cyborg. In his work, this proto-cyborg figure simultaneously symbolizes the intensity of evolving technological restructuring, the new social figures formed through it, as well as technology itself as a tool of domination. In The Iron Hindenburg (1920 drawing), Hausmann presents the eponymous general, a key figure of German conservatism and militaristic spirit, as a monstrous marionette, half human and half mechanical. With his body split open in the middle and metallic and organic parts exposed, a megaphone and military medals in place of genital organs, and a sword in his hand connected to his rear, the general becomes a symbol of a violent, aggressive and sexually dysfunctional authoritarian power. In the photomontage Festival Dada, Hausmann uses the techno-organism as an ironic representation of the petty bourgeoisie, with its proper and submissive ways. Dressed in a suit and seated on an armchair, the plasma’s circulatory system is exposed outside its body; through a complex system of pipes and gears, the circulation is connected to a pressure gauge, a safety valve and a projector that have replaced its head, showing that the petty-bourgeois cyborg’s brain contains no thoughts, but clichés, stereotypical traditional “wisdom” that is mechanically recycled and uncritically projected. In Hausmann’s work, the proto-cyborg becomes an allegory of the rigidity and conformity that characterize the authoritarian personality, as well as a critique of the stereotypical thinking that characterizes both nationalism and the petty bourgeoisie.

A few years later, at the time the Nazis were ascending to power, the figure inspired by Hausmann would be found enlisted in another, opposite cause: from an allegorical caricature against absolutism in the hands of the left-wing critics, that cyborg prototype would be found in the service of propaganda in favor of technological totalitarianism and, consequently, of Nazi power. As the Weimar Republic entered a phase of decomposition, the radical right increasingly embraced the spectacle of technological progress and, within this new framework, the human-machine hybrid made its reappearance. In contrast to the technologized phantom of a decade earlier, the new cyborg figure raises no concerns—it is presented as positive and necessary, just as technology is presented as a positive and necessary force. Among the intellectuals of totalitarianism, the one who dealt most extensively with the issue of technology was Ernst Jünger, who exerted considerable influence on the Nazis. With his work, essays, and publications in which he applied the technique of photomontage (which he had adopted from the Dadaists), Jünger aimed to cultivate a German “new consciousness,” developed around the technology-absolutism duality, which would “save” society from the chaos into which Weimar had dragged it. His contribution to the Nazis abandoning their initial, naive anti-technological positions and adopting a harder techno-totalitarian program was decisive. In his work The Worker, Jünger describes the “new man”—who is no longer a subject but a “type”—with almost cyborg characteristics. The human face is lost behind a mask, and the uniforms, identical and severe, are in reality mechanical extensions of the body. Jünger’s worker-cyborg is characterized by a rigid uniformity and is directly replaceable, thus allowing the cyborg to be “liberated” from particular, individual traits and become part of a larger, hierarchically structured whole. This bio-mechanical totality, which Jünger called an “organic construction,” was to play the role of the supreme principle. Jünger presented his ideas in an even more vivid way in his final and most ambitious book, using his photomontage technique. The Modified World is an illustrated gospel of techno-totalitarianism, with the cyborg starring on a mass scale as worker, soldier, or policeman. Of course, in this nightmarish dystopia, alongside the new type of worker, the “new woman” is also present, who gradually loses her individual characteristics through ever-greater involvement with technology and is shown flocking en masse and in a coordinated manner to beauty salons, in order to fulfill her mission as a sexual accessory and reproductive machine.

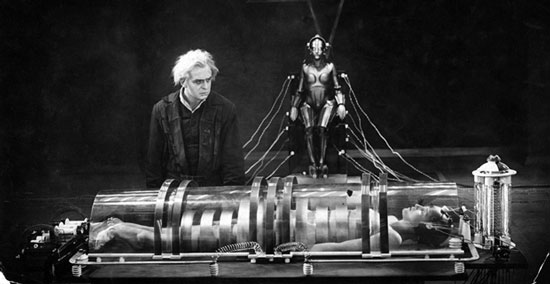

Between these two interwar cyborg harbingers—one from Hausmann and one from Jünger—stands the film Metropolis as a bridge and unifying element between the two opposing extremes. The film narrates the story of a futuristic city with an authoritarian regime and high technological development, strictly divided into two classes: the workers and the ruling class. This city nearly faces destruction due to class conflict, but ultimately survives, leaving its class structure untouched. In the film, the workers live unbearable lives, treated as expendable parts of machines. However, the situation seems to change with the appearance of Maria. The protagonist is a charismatic woman who preaches to the workers, who have become devoted to her. In her sermon, Maria, describing the workers’ unhappy lives, speaks of the “eternal struggle” between the “head” that commands and the “hands” that execute—a conflict that leads to a deadlock unless the “heart,” appearing in the form of a “savior” / mediator, intervenes to restore balance between the two opposing sides. Essentially, Maria preaches passivity and does not threaten the authoritarian structure of the city. However, the master, along with the scientist who serves as his right hand, is alarmed by these preachings that lie outside their strict control. They decide to eliminate Maria and replace her with a faithful replica, a cyborg that will distort Maria’s original message and spread chaos, thus reinforcing their absolute power over the city in the end. Indeed, the scientist kidnaps Maria, imprisons her, and connects her to a series of complex machines that drain her essence and transfer it into a robot. This replica, in today’s terms, is essentially a cyborg—fully mechanical but with the personality of the authentic Maria embedded within. The difference between the cyborg-Maria and the original pure and saintly protagonist is her unrestrained sexuality. In one of the film’s most iconic scenes, the master and the scientist, wanting to test the capabilities of the robot-copy, send it to a club. There, it becomes clear that not only does it possess the natural charm of the original Maria and exert intense attraction, but by openly displaying its sexuality, it has the dangerous ability to manipulate its audience. Indeed, the Maria-cyborg performs an erotic dance, as instructed by its masters for testing purposes, inciting mass hysteria among the audience. The original Maria, the sweet Virgin of the submissive workers—sympathetic and asexual—is transformed through technological modification into an uncontrollable cyborg-whore. As the story unfolds, the sexual and anxiety-inducing spectacle offered by the robot/cyborg provokes such fury and rage among the workers that they eventually rise up with devastating consequences. However, in the end, Maria, who has escaped, together with the master’s son, brings about the long-awaited “compromise” between the “head” and the “hands”4.

Within a span of just thirteen years, from 1920 to 1933, a characteristic invention of Hausmann’s—the mechanized human—transforms from an instrument of critique against totalitarianism into an absolutely functional element of propaganda in favor of totalitarianism. In between, a cinematic film presents a humanoid robot installed with the personality of a natural person, and whose dominant operational characteristic is sexuality—a sex-cyborg, nine decades before our time. This domestication of the “left-wing” techno-organism, first by mass culture in the form of the sexual machine and subsequently by the far right in the form of the subjugated-mass-worker-cyborg, is a sequence we must bear in mind upon returning to our own era; it may prove extremely timely. Moreover, it guarantees the anachronism we attempted: if elements of the cyborg are identified in the period preceding its invention, it is because it is deeply connected to totalitarianism.

Liberated machines and bound bodies

In the second half of the 20th century, the intersection of technology and sexuality through the projection of sexual attributes onto machines reached such a degree that it has now become an integral part of mass culture. For the average Western person, machines had been humanized, having first been sexualized; they became “masculine,” “beautiful,” “erotic,” “desirable.” The epitome of this techno-eroticism is undoubtedly the automobile, the diamond in the crown of industrial capitalism. In David Cronenberg’s 1996 film Crash, based on J. G. Ballard’s 1973 novella of the same name, the protagonists experience sexual attraction and fulfillment only in relation to the car, and specifically in the most extreme condition: at the moment of serious car accidents following collisions, as the body is brutally injured and mutilated. Equally alluring with strong sexual attraction is the body deformed by surgeries, with metallic rods, blades, and unnatural scars evoking the metal of the car and its folds. While these transgressive sexual practices seem to belong to the category of the “unnatural” and the exception, a dramatized case of techno-fetishism, in reality excessive violence and pain are both results of the desire for union with the machine and simultaneously the means of fulfilling it; it is the extreme version of the fulfillment of the desires of the average secular person in relation to his car. The director, commenting on the film, had described the automobile as “a mobile bedroom,” a technological symbol of sexual performance that fundamentally shapes modern relationships. “We have already incorporated the car into the way we perceive time, space, distance, and sexuality. Wanting to literally unite with it, in a more physical way, seems like a good metaphor. There is a strong desire to merge into technology.” Ballard, for his part, commenting on the future of sexual relationships, had said that “organic sex, body against body, skin against skin, is becoming increasingly difficult… Where we are heading is a completely new order of sexual fantasies, including other types of experiences, such as car crashes or jet flights, anything related to the entire spectrum of new technologies.” Welcome to the sexual touch of the 21st century!

Today, in the age of the biopolitical paradigm more than ever, so much ground has been covered that machines as carriers of sexuality and representations of objects of desire have been crafted in such detail (the contribution of advertising, for example, would require special mention on its own), that the minds of spectators nurtured by the spectacle of primal worldly citizens are mature enough to accept and embrace any kind of mutation and intervention upon the body. The desire for “enhanced” and technologically shaped sexuality that transcends the “limitations” of the body is not an invention of our digital age. It bears the specific characteristics befitting its case, yet simultaneously carries a range of features that were shaped in the past, in the realm of art forms and mass culture, along a trajectory beginning with fantasies about “automata” and culminating in the worship of the automobile and the cyborg of Metropolis. Hardness and supernatural abilities, when technological fantasy assumes masculine traits; allure, submissiveness, and sexual skills, in the corresponding feminine case; the suffocating constraint of the body within mechanical extensions and the brutal interventions upon it—in essence, the transformation of the body into an open field for the development of technological applications; the production of pain and violence as a constant component in the intersection of the living with the mechanical; the worship of technology as a force that will “liberate” from the flesh and lead to a post-human level—all these elements that characterize cyborg sexuality are products of the historical journey of the body’s relationship with technology and the attempt to subordinate the former to the latter.

Despite the historical depth of the relationship between technology and sexuality, and despite the continuity that exists between the mechanical past and the digital present, there is a contemporary condition that radically changes things: what yesterday (the historical yesterday) was a tendency, pursuit, experimentation, or prediction, has ceased to be “gestated” and is today a harsh reality, with absolutely material and practical manifestations. The desire for “diffusion into technology” and sexual “enhancement” through intersection with machines is no longer the subject of fictional creation, but of industrial production, commerce, and mass culture. The series of already applicable cyber-sex technologies will surely surprise those uninitiated who remain attached to the ways of the civilized homo sapiens. Starting from the mind and the senses, the – new in the field of sexuality – neurochemistry is already working on the broad spectrum of inhibitions that limit sexual activity. Anxiety, shame, guilt, depression, and other inhibitory psycho-emotional conditions have become targets, whether of new drugs or adaptable cyborg implants that act neurologically and either trigger or intensify libido. In biology and medicine, with gene therapies, 3D bio-printing of tissues and organs, and advanced surgical interventions, the body is transformed into malleable biological matter. In the field of technological applications over the internet and virtual reality, various devices and applications are already defining the framework of digital, remote sexuality. As Atwood mentions in her introduction, for the initiated, devices like teledildonics are what smartphones are for everyone else. These are devices applied to the genitals, connected via computer to the internet, and through appropriate software, they allow virtual sexual contact—in effect, mutual masturbation through electronic mediation.

“Soon we will be able to change almost all the characteristics of our biological self relatively easily. Skin color, gender, and age will shift from genetic determination to personal choice… Neurologically, we will be able to turn any part of the body into an extension of our genitals. Stimulation from fingertips, the nose, the palm, anything – we will be able to redesign the sexual body in any way we desire.” This orgasmic prediction of impending developments—sourced from the website futureofsex.net—is indicative of the intensity and scope of experimentation surrounding cyborg-sex: an inverted sexual intercourse, which is in reality extreme technofetishism aimed at the complete technological mediation of desire and the body. The next extensive excerpt, more specific and “realistic,” also comes from the same website. The article’s title is “Enhancement Interventions in the Bedroom: Biohacking and the Inevitable Cyborg Sex.”

Have you ever wanted to upgrade your body? To make improvements against biological limitations? To build a better version of yourself? What would you say to enhancing your sex life?

Biohacking is a revolutionary scientific practice, both cutting-edge and terrifying. Approaching the human body in a hacker-like way, it includes a wide variety of practices, from cyborg enhancements to gene interventions and biological mutations.

The grinders, as they self-identify, are a community of futurists operating on the fringes, aiming to become the first cyborgs in history. They support an open, upgraded culture and operate in a bizarre field combining body modifications, techno-fetishism, and DIY surgery. And some of the advances they have begun to make are truly astonishing, so much so that someday we might even engage in cyborg sex.

[…]

Introducing the Lovetron9000

Rich Lee is a biohacker who caught the media’s attention in 2013 when he surgically implanted neodymium magnets in his ears. Aiming to compensate for his deteriorating vision, he plans to connect his implants to an ultrasonic spectrum detector. By producing tones that indicate distances from objects, Lee ultimately wants to learn to “see” through echolocation. Like many grinders, Lee turned to biohacking due to his desire to overcome a disability, but has since moved on to enhancements.

Lee now promises that his new implant under development – the Lovetron9000 – will radically change the nature of sex. Speaking to “future of sex” about his research, Lee highlights the benefits of cyborg sex and discusses what biohacking has in store for us in the bedroom and how the Lovetron9000 will upgrade the penis. Lee was inspired to create the implant in 2011, influenced by classic science fiction… Implanted within a layer of fat, the Lovetron9000 has a small motor to cause vibrations in the penis. The battery is inductively charged, requiring only a special charger placed on the leg… A version with textured surfaces is being prepared, which Lee claims is “very kinky” – all for your partner’s enjoyment.

Though it walks the line of shock, society has gradually become accustomed to the prospect of biohacking. The ubiquitous presence of smartphones along with wearable technologies have already begun to blur the distinction between machine and person. But while a smartphone may not be as alarming as a cyber penis implant, we have already integrated technology so deeply into our lives that the differences are negligible.The cost of mixing

Going under the needle might seem like a drastic step to some, but Lee claims the procedure won’t be overly invasive. As with other biohacking implants, the plan is for the procedures to be performed by body artists rather than surgeons.

[…]

Regardless, the grinder lifestyle is certainly not a choice for everyone, especially those with weak stomachs. Central to the DIY biohacking punk ethos is an almost masochistic approach to the body as a testing ground for new technologies. Typically, these implants are inserted without anesthesia, although this has less to do with some painful ritual and more to do with the legal protection of those responsible. Surgical intervention without a medical license is a crime, and the absence of anesthesia allows biohacking to be classified as aesthetic procedures rather than medical practices.

Keeping such interventions in the hands of practitioners serves another purpose: keeping them cheap. “If surgeons get involved, the cost will skyrocket and then only the rich will be able to afford the Lovethron9000,” says Lee. Accessibility is fundamental, as Lee envisions a future where implants will be commonplace: “Having sex with a cyborg will be amazing. Imagine sex, but with deep, unnatural, and exciting stimuli. The cyborg will be both donor and lover at the same time. The question is: after something like that, will you be willing to return to sex with non-cyborgs? No, you won’t be satisfied by humans anymore. Game over humans!”Strange horizons

Lee plans to develop even more sexual biohack devices, including one for women. Implanted in the genital area, the device would cause pressure generated by electromagnets placed on either side of the clitoris. “I encourage my acquaintances to stop me before anyone gets hurt,” Lee jokes.

Lee is not the only one trying to improve sex. A company called Sweet Peaches Probiotics recently caused many controversies with its entry into the biohacking game. Its plan to develop a nutritional supplement that would allow women to hack the scent of their genital organs to smell like fruit caused equal enthusiasm and anger.

Lee confirmed to us that there are other grinders with similar development plans. Specifically, he referred to “crazy biological things that would change the taste of sperm or eliminate the natural time a man needs between orgasms.”

But will these new technologies have a positive impact on our sex lives? According to Lee, the future of biohacking ranges from dark to bright and depends on how we embrace it. “I can imagine people with implants in their spine using sexual stimulation as a reward when they manage to electrify everyday things. I can also imagine jealous or controlling lovers putting passwords on their partners’ devices as a kind of chastity belt. Or perhaps the church asking us to take an oath of abstinence and continence, so the devices would be set to disrupt signals of sexual pleasure. There are all kinds of strange horizons to explore.”

cutting edge sexuality or otherwise how the body becomes the “base” of the machine:

Fucking cyborgs

If there is something that deserves more attention in the above excerpt, it is not so much the extremism of the experiments that some “pioneers” imagine and try out, as the following two points. First, the approach and treatment of the body as a fragmented set of organs and individual parts, corresponding to different sets of implants and interventions. In this way, combined with the proclaimed “easy access” to new technologies, the body is transformed into a disassembly/reassembly factory. Second, the “philosophy” of diffusion and socialization that permeates such practices. And if groups like the “grinders” develop in fringe areas, behind them, in less shocking ways, there is also a host of laboratories, research centers, scientific organizations and companies oriented towards computer science, chemistry, medicine or even the sex industry, working systematically on the issue of technological mutation of sexuality. From enhancing chemical compounds to apps that record, measure and regulate sexual habits, the sex cyborg is here. This is a crucial qualitative difference – a difference in the conception of technology, and a difference in relating to technology – from the past: today the technologization of sexuality – and vice versa: the sexualization of technology – is a diffuse social routine, commonplace, established practice. Moreover, because in modern society sexuality, as in previous centuries of history, continues to be a taboo issue, a generalized technologization here functions as a battering ram everywhere. A society that has become accustomed – or at least is making leaps towards this familiarity – with cyborg-sex, how and why should it react, for example, to the figure of the cyborg-worker or the totalitarian, panoptic cyber control?

The development of technology and the expansion of mechanization gave rise in the first industrial societies to the fear of possible consequences, which, in its extreme expression, had as its object technology that escapes control and develops against its masters. It is the fear that plays the leading role in Mary Shelley’s gloomy and macabre narrative about the monstrous offspring of technology that acquires self-consciousness. Inverted, this fear turns into metaphysical worship, and it is this that is implied in the two excerpts we present at the beginning of the text: technology has developed to such a degree that it has sexually matured and reproduces on its own, having transformed humanity into a mere reproductive organ. A techno-metaphysics with technology in the role of the “supreme being.” This fetishistic duality of fear/worship, with its sexual connotations, is not appearing for the first time today. Nor is it the first time today that technological capabilities are deified, because it is supposed they will “liberate” us from the prison of the flesh and the limitations of the body or lead us to the technological Promised Land. Such phenomena historically belong to the spectrum of totalitarianism. When Ernst Jünger, that harbinger of Nazism, promoted in the interwar period the “new man,” cyborg workers, and dominant technology, the social model he described was that of techno-fascism. Today, he would observe that this model is more imminent than ever.

Harry Tuttle

- Margaret Atwood is a renowned Canadian poet, novelist and essayist. In 2004 she conceived and participated in the team that developed the LongPen remote writing robotic technology, initially intended to allow authors to sign their books without the need for physical presence. Today LongPen technology has extensive application, especially in banking and commercial activities. ↩︎

- The Weimar Republic was the German state that succeeded the defeated German Empire of the First World War and was dissolved when the Nazis came to power. Although it effectively crushed the Spartacist uprising in January 1919, it proved extremely fragile and temporary, a brief interim stage of social democracy and liberalism before the establishment of the Nazi regime. Its short lifespan, only 14 years, was marked by turbulent sociopolitical processes both on the left and the right, ongoing street conflicts, an intense and avant-garde artistic movement, but also a severe economic crisis. ↩︎

Born amid a war that brought an end to the German monarchy and a revolution that was defeated, operating under conditions of daily social and political violence, the Dadaist movement was a profoundly political and critical movement. Its basic positions were, on the one hand, that the revolutionary momentum of 1918–19 had been extinguished, and on the other, that despite the general liberalization following the war, the authoritarian forces that had led to the catastrophe had not been defeated, but had merely retreated temporarily and were actively working behind the scenes to seize power once again. The targets systematically opposed by Dadaism were German militarism and nationalism, as well as the petty bourgeoisie, which was viewed as the main source of support for authoritarianism.

↩︎- The finale is so dramatic that the main conclusion takes a back seat: despite the compromise, nothing has changed and the new state does not differ at all from the previous authoritarian regime! ↩︎