When it comes to the consumption and use of electronic products/goods, one can often observe phenomena of fandom among their users/consumers. The battle over which is the best mobile phone against the competition, which is the best operating system for PC or the best program for a specific use (e.g. design) gathers around the respective products a large number of paid or unpaid publications in electronic portals, comments, links, and other electronic noise, which sometimes simply declare loyalty to a company, while other times they are accompanied by extensive technical texts that justify the preference of the author.

Within these popular search frameworks of the “X vs Y” type, one may come across the question “Windows vs Linux.” Thus, one might encounter for the first time the terms free software or open source software, which concern not only the Linux operating system, but also a multitude of other programs intended for use on computers. With a second (tailored) search of the previous terms, our example navigator may discover that they are facing a sea of information and opinions that go beyond technical issues and extend into philosophical, even political matters. They might, for example, see that the aforementioned software categories challenge monopolies in the software market and, to a lesser or greater extent, limit or eliminate the enforcement of intellectual property rights on the “source code” of each respective program, using an inverted version of copyright (copyleft).

Going even further, and perhaps now completely departing from the consumerism fandom we described at the beginning, you will discover a wide range of academic research and theoretical analyses regarding peer-to-peer (p2p) production based on the “commons”, views on cyber-communism, expectations for changing the production relations of the capitalist system from within, cultural analyses of the hacker community and their ethics, liberal views on the significance of “open” in contemporary capitalism… There is no doubt that among the topics of “new technologies and politics”, issues around open-source software are among the most debated. To such an extent, that it is impossible to attempt a sufficient mapping of the circulating views here. Even more so, if we take into account that the characterization “open” – more than “free”, and we will see below why – has expanded and accompanies a plethora of initiatives, movements and institutions, ranging from the liberal demand for open access, transparency and collaboration to open data, open education and even open government.1

In any case, what should be recognized is that the history of free software and subsequently open-source software constitutes a central point of reference for those who try to engage in politics based on the concept of “openness” – and they are not few. As we realize that this concept is acquiring an increasingly prominent position in the rhetoric of technological restructuring, we will initially approach the history of free software. It is difficult, when searching for this history, to avoid the “mythology” that surrounds it, mainly due to the existence and role of personalities in the field within which it unfolded.

The following text consists of selected excerpts from Cristopher Kelty’s book titled “Two Bits: The Cultural Significance of Free Software” 2, which, in several parts, manages, in our opinion, to slip away from this mythology of personalities and delve more into the substance of the matter. In these excerpts – whether intentionally or not – the author outlines, through specific snapshots from the history of free software, a set of social, economic, legal, technical – ultimately political – processes and operations related to the sphere of production of electronic commodities, in the category of software. In the following texts, through our own notes, we will attempt to bring back some issues arising around software production from the cloud of consumption and academic (left-wing or/and liberal) chatter to the contemporary reality of capitalist production relations.

for the birth of the fox (Firefox)3

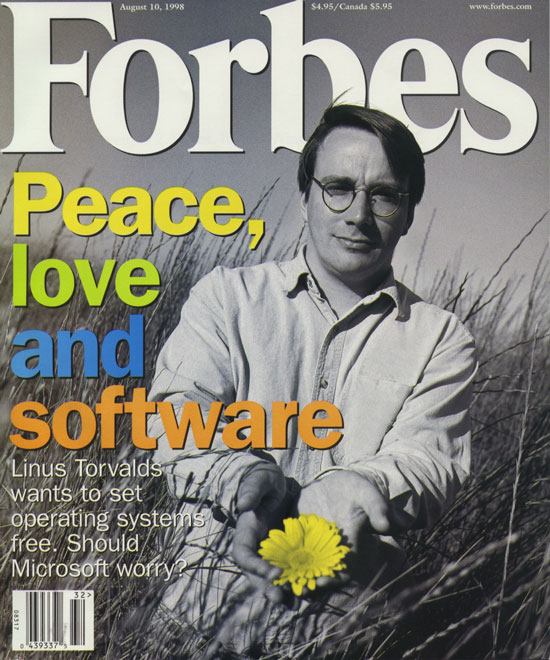

Free Software and its origins can be recounted in detail through the historical narrative of specific kinds of practice: the creation of a movement, the sharing of source code4, the conception of openness or open systems, the drafting of copyright and copyleft licenses, and the coordination of collaborations. All these stories together describe Free Software. These stories reach their climactic moment (or their starting point, speaking genealogically) in the years 1998–99, when Free Software burst into the spotlight: on the cover of Forbes magazine, as part of the dotcom bubble, and in the conference rooms of venture-capital firms and corporations such as IBM and Netscape.

…

The first of these practices—the shaping of Free Software into a movement—is both the immediately obvious and the more difficult to understand. By the term movement, I refer to the practice among geeks of arguing and debating the structure and meaning of free software: what it consists of, what it is about, whether or not it is a movement. Some geeks call Free Software a movement, and some do not; some speak about the ideology and purposes of Free Software and some do not. Some call it Free Software, while others call it Open Source. Nevertheless, despite these disagreements, Free Software geeks recognize that they are all doing the same thing: the practice of creating a movement is the practice of talking about the importance and necessity of the other four practices. It was in 1998–99 that geeks came to recognize that they were all doing the same thing—and, almost immediately, to disagree about why.5

…

One way to understand the movement is through the story of Netscape and the Mozilla Web browser (now known as Firefox).

…

Free Software branched in 1998 when the term Open Source suddenly appeared (a term previously used by the CIA to refer to unclassified sources). The two terms resulted in two different kinds of narrative: the first, concerning Free Software, goes back to the 1980s, promoting software freedom and resistance to the “enclosure” of proprietary software, as Richard Stallman, head of the Free Software Foundation, calls it6; the second, concerning Open Source, is associated with the dotcom bubble and the pro-business preaching of Eric Raymond, who focused on the economic value and cost reduction represented by Open Source, including the pragmatic (and polymathic) approach that prevailed in the everyday use of Free Software in some of the largest online start-ups (Amazon, Yahoo!, HotWired, and others “promoted” Free Software by using it to run their stores).

…

What precipitated this attempted semantic coup was the release of the source code for Communicator, Netscape’s Web browser. The significance of Netscape for the fortunes of Free Software is difficult to overstate.

…

Netscape’s decision to share its source code might seem unexpected only within the context of the widespread practice of keeping source code secret. Secrecy was a widely followed practice aimed at preventing competitors from copying a program and releasing a competing product, but it was also a means of controlling the market itself.

During the 1990s, the “browser wars” caused both Netscape and Microsoft to stray from this vision: each had implemented their own extensions and “features” in browsers and servers… These implementations contained various kinds of “evil” that could cause browsers to malfunction on different operating systems or specific types of servers.7 The “browser wars” repeated the battle of open systems from the 1980s, a battle in which the effort to standardize a network operating system (UNIX) was hindered by competition and secrecy, while at the same time consortiums dedicated to openness were formed in order to prevent the spread of evil. Despite the fact that both Microsoft and Netscape were members of the W3C [World Wide Web Consortium], the incompatibility of their browsers clearly represented manipulation of the standardization process in the name of competitive advantage.

The public release of the Communicator source code was thus seen as perhaps the only way to circumvent the poisoned well of competing, non-standardized browser implementations. An Open Source browser could be created to comply with standards—if not directly by those involved in its creation, then by creating a standards-compliant fork of the program—thanks to the redistribution rights associated with the Open Source license. Open Source would be the solution to the open systems problem that had never been solved because it had never directly confronted the issue of intellectual property. Free Software, on the other hand, already had a well-developed solution in the GNU General Public License (GNU GPL), also known as the copyleft license, which would allow software to remain free and revive hope for maintaining open standards.

…

However, Netscape immediately became embroiled in a battle with Free Software hackers because it chose to draft its own proprietary licenses for distributing the source code. Instead of relying on existing licenses such as the GNU GPL, the Berkeley Systems Distribution (BSD), or MIT licenses, it created its own: the Netscape Public License (NPL) and the Mozilla Public License. Netscape’s immediate concerns had to do with its existing network of contracts and agreements with other third-party developers—both those who had contributed parts of the existing source code (which Netscape could not redistribute as Free Software) and those who expected to purchase and redistribute a commercial version in the future. The existing Free Software licenses were either too permissive, granting rights to third parties that Netscape itself might not possess, or too restrictive, binding Netscape to make the source code freely available (e.g., GPL), while it had already signed contracts with buyers for non-free code distribution. To appease the Free Software geeks, Netscape drafted one license for the existing code (the NPL) and a different license for new contributions: the Mozilla Public License.

…

One of the key selling points for Free Software, especially when marketed as Open Source, is that it mobilizes the work of thousands or hundreds of thousands of volunteer contributors via the Internet. Such a claim leads to a spurious discussion about “self-organized” systems and the emergent properties of distributed collaboration. Netscape’s press release promised to “harness the creative power of thousands of programmers on the Internet by incorporating the best of their enhancements”… “By releasing the source code for future versions, we can unleash the creative energy of the entire online community and fuel unprecedented levels of innovation in the browser market.”

…

Software engineering is evidently a difficult problem. The halls of the software industry are littered with the corpses of dead software methodologies serving as grim warnings. Software development during the dotcom boom differed only in that the speed of software release cycles and the pace/intensity of funding (over-funding through venture capital, exceeding revenues, the “burn-rate”) were faster than ever. Netscape’s internal code development methodologies were designed to cope with these pressures, and as many working in the field can confirm, this method is some version of a semi-structured process driven by deadlines, caffeine, and energy drinks in the race to the next release.

The public release of Mozilla’s code, therefore, required a coordination system that would differ from the usual internal software development practice carried out by paid programmers. It needed to incorporate contributions from outside the established cycle – developers who did not work for Netscape.

…

Briefly, if some magical Open Source self-organization was to take place, it would require a fully transparent, Internet-based coordination system.

At the beginning, this practically meant acquiring the domain name mozilla.org; setting up (and then posting the source code to it) a version control system (Free Software standard cvs), the interface of the version control system (Bonsai), the “build system” that managed and displayed the various trees and (broken) branches of a complex software project (Tinderbox), and a bug-reporting system for tracking bugs submitted by users and developers (Bugzilla). It required an organizational system within the Mozilla project, where paid developers would be assigned to review submissions from both inside and outside, and maintainers or editors would be assigned to examine and approve whether these contributions should be used.

for property relations

The story of the previous text focuses on a truly pivotal point, not only for the evolution of software production processes in general, but also for creating sustainable terms for expanding internet usage. The compliance of web browsers with specific standards was, and continues to be, a fundamental prerequisite for the proper functioning of internet access for all business and consumer activities that relate more or less to the ability to access any website at any time. The foresight of Netscape’s executives proved extremely accurate: “By giving away the source code… we can unleash the creative energy of the entire Web community and fuel unprecedented levels of innovation in the browser market”; and not only that, we could add today.

With the public announcement of the code, forces that gradually led to the acceleration of the development of the informational arm of capitalist technological restructuring appear to have been unleashed. The productive forces in this sphere of production, particularly in the case of software development, are constituted by the unprecedented capabilities offered by collective labor in combination with the technical means of PCs and networks.

This “potential,” having already made its presence felt—albeit initially limited to the underground space of hackers, geeks, and within some academic institutions and companies—is systematically attempting to emerge into the spotlight of the new entrepreneurship; onto the surface of cutting-edge technology development. At the same time that the practice of sharing code challenges, often under a liberal or even apolitical ideological guise, intellectual property over code creation, this very form of ownership and its extensive subsequent market application appears as an obstacle to technological development itself. For this case, it would be as easy as it would be wrong to simply speak of the integration of a movement.

With a first purely ideological, superficial and general approach, one could argue that one liberalism (that which has its origin in ideas about freedom of speech) came into conflict with another liberalism, that which has its origin in respect and protection of property.

The first appears markedly progressive compared to the second—the laissez-faire attitude of open source code, even under the most restrictive (for proprietary appropriation) copyleft licenses, never intended to hinder the sale of products in the software market or the profitability of a new type of business. On the contrary, it seems to have created the conditions for normalizing competition, expanding markets and corresponding new forms of entrepreneurship. Moreover, it would create opportunities for establishing new “enclosures.”

Here, however, the theoretical framework of “commons and enclosures” struggles to find its clear practical application. This is because, in the case of free software, a release at one point can often signify the de facto creation of a new “enclosure” slightly further inward within the same sphere of production, even on the very same product that is being “released.” In practice, this is reflected by the plethora of license variations written around the rights of use, modification, and redistribution of the software’s code.8

While these may have as a common starting point the left (in the sense of copy-left) end of the GNU GPL, depending on the market requirements around the distribution of the product, their authors can bend and lean towards the right end of copy-right. This flexibility of ad-hoc application or rejection of intellectual rights did not come only as a market response to the “commons” of creators, but also fit like a “glove” the trade-off between the cheap and at the same time hyper-productive labor of communities and revenues from intellectual rights.

One thing is that all these licenses, from the most copy-left to the clearly copy-right, are rarely read in their entirety. Even for the most “ideological” person, such a thing would be demeaning. Unless that is how he “makes his living.” The aforementioned Richard Stallman, founder of the Free Software Foundation and publisher of the GNU GPL, is exactly such an example, as he has been writing articles on these topics for years and giving lectures at institutes around the world, evangelizing the true freedom and democratic rights of creators and users of software.

A second, and more important, point is that the productive forces themselves, as they develop, come into conflict with intellectual property, and are mobilized to extend property relations into new markets that are dynamically created. This concerns the orientation, use, and operation of software, regardless of the type of license its code carries. The direction of investments related to open source software today – on a scale comparable to the dotcom bubble of the late ’90s – circulates under the buzzwords “cloud computing” and “big data analysis.” In this contemporary example, if the software code is not subject to intellectual property rights, but the data it manages or analyzes is owned by the respective company, then what? Is everything ok? The counterargument, that when the code is open the community of users (some more “expert” within it) can study it and determine whether it leads to “surveillance” analysis of data, cannot mean much in the post-Snowden era. Perhaps only attributing an indefinite sense of positivity to the concept of openness, of the kind “we want to be able to know if and how you are monitoring us.” Whether in the case of “hidden” extraction and analysis of data or in that of voluntary assignment, as well as in all intermediate situations (e.g., assignment due to ignorance), the data (ours), which in any case circulate freely on the network, become “enclosed” as they come under the ownership of a company, which very well might use free software with publicly available source code in its infrastructure.

Should the issue of openness, then, be extended to data as well? A new term that has become fashionable lately is open data. But what happens when this data is open to anyone? If it is open to anyone, then it is certainly more open for open-data companies that can analyze it, package it into a product, and sell it. New dynamic forms of ownership are emerging again, the concept of openness is expanding, and thus things become even more complicated…

for the community and the exploitation of labor

As a first conclusion, we can at least retain this: the high (highest!) productivity of labor based on high levels of cooperation and interdependence, what is referred to as increased sociality of labor,9 can lead to the overcoming and questioning of ownership, in our case intellectual property, even without requiring the subversive disposition of some movement beforehand. Precisely for this reason, at the same time or even preemptively, capital, through the strategy implemented by the most “progressive” companies in each field of production, takes care to create new markets where property relations are dynamically reinstated.

If the questioning of ownership constitutes a temporary crack in the reality of a rapidly changing world, this crack must be covered by the rapid change itself. This is not an exception within an alleged capitalist normality, but is the central reality of capitalist crisis/restructuring. What then is the constant among these cracks? It is none other than labor and its exploitation; the maintenance of its subordination to capital, on the narrow basis of property relations.10

Theories about peer production based on “commons” as an improvement and/or transcendence of capitalist production relations and alienation, or even the “sanctification” of intellectual labor as an immaterial and ethereal act extending beyond working time, emerged and became fashionable as viewpoints during the 2000s, up until the outbreak of the latest acute phase of capitalist crisis/restructuring.

Many academics, of both liberal and post-Marxist persuasions, “smelled a rat” and rushed to embrace open source production processes as exemplary. Not long after, however, company executives and startup promoters, as well as advertisers from older firms, hurried to set up smaller or larger operations all over the world at breakneck speed, preaching the freedom of open source code; they were simply doing their job. For this reason, we will set aside the theories of academics for the time being and try to focus instead on the reality of production relations.11

Software developers, as part of the digital proletariat (as opposed to well-paid executives and managers who multiply like amoebas), continue to suffocate while frantically typing away at their keyboards.12 Since the largest part of software production costs corresponds to “development costs,” i.e., labor, minimizing wages to the point of voluntary “free” work is a constant pursuit of companies in the industry. The same arguments that may seem radical to some actually reinforce traditional managerial clichés: “what matters is that you enjoy what you do,” “we’re all one big family here built on participation and collaboration, and we’re all equals,” “we don’t call it overtime here… it’s… what do they call it? our way of life”(!)… All of this constitutes an inverted version of adopting increasingly strict tools for controlling intellectual labor, through its quantification and breakdown into small, manageable sub-tasks. The measurement of lines of code committed daily by programmers and the recording of modification histories, the automated analysis of code quality based on specific “correct coding” criteria, the use of online project management tools even to measure “pure” working hours, the estimation of progress toward achieving goals or deadlines, and the evaluation of burndown13 are just some of the tools used in modern management of small or large software development companies. These tools may be open source, or they may not be, and the same goes for the products they produce—who cares? Just as with the Mozilla project back then, so now, there is no magic of self-organization of the community in applying all these tools. Instead, stress, competition, and performance prevail.

The programmers themselves, who now may prefer the trendier term “developers” and like open-source, when working under these conditions, find it difficult to resist the stress caused by their management. At the same time, leading open-source companies compete over which one will incorporate the most cheap, if not free, work from the long-standing communities of free software into their services, while simultaneously promoting the image of the well-paid executive for their salaried employees “at headquarters”.

for profit and surplus

A question that may arise here is how these companies ultimately profit and develop? Microsoft’s business model is clearer. Its core products are protected by copyright licenses, so by keeping the recipe secret, it can create monopolistic market conditions, while also providing accompanying support services. Additionally, since its software code is proprietary, it can generate profits by licensing rights to third parties.

In the case of open-source software, a company can certainly sell the software as a product. Moreover, depending on the license accompanying the code, the future “closing” of it by the same or another company may be allowed or prohibited. In any case, the code can theoretically be used from its last open version by any community of programmers.14

The productivity of the work continues to increase at a frenzied pace, the developers who contribute are increasing, while the large companies (the Top 15 is shown at the end of the info-graphic) have been involved for years for the good in the game of developing the crown jewel of open-source.

The participation of company employees, according to the most detailed data provided by the Linux Foundation on its website, for 2008 exceeds 70% (the largest part of which is attributed to the “Top” companies), 13.9% are reported as unaffiliated with any company (possibly volunteers), while 12.9% of contributors are of unknown association with any company or organization.

The corresponding numbers for 2015 are more than 80% for company employees, 12.4% for those who are not paid for this by any company, while those of unknown origin are at 4%.

This means that if a competing company can attract a significant portion of the community and decides to distribute both the code and the software for free, the value of the original company’s software product is diminished. Due to this peculiarity of competition among such companies, most of them owe their profitability to the provision of services that accompany the sale of the product. Bug fixers, maintainers, developers, system administrators, as well as sales and technical support call centers—whether established by the company itself or as subcontractors—contribute to providing just-in-time upgrades, support, and promotion of the software products. The free voluntary work of communities is combined with paid labor and the more “traditional” methods of exploiting wage labor, where salary levels are determined according to the country where the company’s offices are located each time.

Characteristic is the example of Red Hat, one of the largest companies of its kind, which primarily trades open source software packages, with its flagship product being the Red Hat Enterprise Linux (RHEL) operating system and the support services around it.15 Red Hat on one hand supports and is supported by the Fedora Linux distribution community, which is distributed for free. Community participants sign an agreement (Fedora Project Contributor Agreement) which specifies the types of intellectual property licenses that can be applied to their contributions. This way, new features can be tested and evaluated, issues can be reported and resolved by this community as well as Fedora users, before being reviewed by paid staff and integrated into a future version of Red Hat’s final commercial product.

At the same time, because the code of each new version of the commercial RHEL operating system is mandatorily made public, due to the copy-left licenses accompanying its individual components, free versions of the commercial software itself can emerge. One such example is the CentOS Linux distribution. Red Hat not only does not object to the existence of a free distribution that is identical to its commercial product, but on the contrary, in 2014, it incorporated the key contributors of this distribution and now supports the rapid – and always free – release of CentOS, which accompanies each new version of its commercial operating system. This way, it controls two versions of the same operating system: one accompanied by paid support services (RHEL) and a second, almost identical to the first, but without support services (CentOS).

The second, as it is distributed free of charge, has a large community of users and “volunteers” who in turn contribute to the improvement of the product. Within the “user community”, many are employees of companies that prefer to avoid subscribing to acquire the commercial product and delegate the resolution of any problems, whenever they arise, or the implementation of improvements, when needed, to their employees, who are encouraged to participate in the respective community (where others like them, from other companies-“customers”, also participate). In this way, Red Hat gains in product improvement, as the community that exploits it can now also include employees (with quite specialized knowledge) of other companies-“customers”, even though it apparently loses from sales. On the other hand, the company-“customer” adopts a labor intensification model, where “problem solving” usually constitutes a classic, possibly unpaid, overtime, while at the same time it also exploits a share of “free” labor, utilizing the tremendous productive capabilities of the collective work of the communities within which any problems are resolved.

What happens however when companies such as Red Hat compete in the same market with companies such as Microsoft? In the case of software where the largest part of production costs are salaries, the average price of the final product is largely determined by the average salary across the entire production sector. Therefore, a company that deploys an innovation that dramatically reduces production costs, in our case salaries, will dramatically increase its profits, its stock prices, etc. In this way, the surplus that the company applying such an innovation will receive is also due to the existence of a sufficient number of other competitive companies that have not yet adopted a similar innovation that would reduce their production costs as well. In our example, Red Hat’s innovation against Microsoft is the deployment of large amounts of cheap or even free labor which, moreover, due to its communality, proves to be hyper-productive compared to classical corporate models, producing products of often superior quality.16 In other words, the maintenance and increase of profit from surplus value for companies that produce and trade open source software is due to the coexistence within the same market of the low average salary internally (due to the exploitation of community labor) with the high average salary in competitive companies. The “innovation” here, when simply understood as such, conceals the exploitation of labor and is called crowdsourcing. The composition of such a crowd is not one-dimensional. It is not simply about some geeks.

A year later, in 2010, Sun was acquired by Oracle, which in various instances attempted to halt the open source games; after all, the Solaris operating system had already been undermined by GNU/Linux. You can imagine: Panic in the communities!

for programmers (or developers – same thing)17

After two or three decades of processes of community exploitation by companies, the once “geeks’ volunteering” clearly takes on characteristics of underpaid work or/and free labor as self-education for one’s resume. What are the elements of subjectivity of this “crowd” under conditions of crisis? On one hand, programmers feel relatively secure, if not from the fear of dismissal or unemployment—which always plays a role; one only needs to see the announcements of job cuts even in IT giant companies—but mainly by positioning themselves outside the “remaining” job market, where the difficulty of finding work there seems much greater. Alongside the classic careerism accompanied by the undervaluation of other jobs that are “inferior” in salary and status, what plays a particularly important role concerns a peculiar “care of the self” that necessarily includes the cultivation of knowledge and skills related to work, during time off from work.

The now outdated term “programmer,” in the ’90s, denoted not simply a profession but also a social figure that could be perceived as the mainstream of hackers, while on the other hand, could overlap with the certainly broader set of yuppies. This figure, the “programmer,” was primarily that (a programmer) throughout both his working and non-working time, with anything else being secondary. This is yet another identity resembling the commodified (sub-)cultures of the post-’70s era, defined both by work and by the consumption and modification of the use of machines, software, and gadgets during non-working hours.18 However, in our subject—which at this point is nothing other than the exploitation of this “self-care”—this “care” (whether translated into participation in amateur online programmer communities or into individual home projects that never make it online) constituted, and continues to constitute primarily, a free—for the employer—form of high-quality self-education, often superior to any known relevant academic degree (bachelor’s, master’s, PhD). At the same time, it represents the holy grail for recruiters in the human resources departments of companies. These executives should somehow be able to recognize, distinguish, and categorize the abilities and skills of a good programmer from those of a not-so-good one.

An official starting point for this “story” can be traced to a conference sponsored/organized by the NATO Science Committee in October 1968.19 The title of the conference was the then newly coined term “Software Engineering,” which subsequently became the banner of a new class of personnel. Their job is to break down a software project into smaller parts, enforce standards, and define evaluation criteria during software development. In this way, they attempt to achieve standardization, classification, and recognition of the corresponding skills and competencies required from a programmer. Moreover, while code could become the property of a company, this would not mean much if the only person who could understand and modify it was its original author. Since the birth act of Software Engineering, much has intervened in the field of organizing coding methodologies, monitoring and controlling work, the quality of the outcome, and the assessment of developers’ skills. Above, in the text “on sociability and the exploitation of labor,” we referred to some of the modern management methods and the corresponding tools used. The similarities and differences between them and the Taylorism of Fordist factories remain to be explored and analyzed.

As for showcasing and evaluating programming skills nowadays, a developer’s electronic resume tends to include much more than a simple pdf containing a few scattered programming languages. An increasing number of employers seek both qualitative and quantifiable evidence of candidates’ abilities by reviewing their contributions to open source projects online. A characteristic example is the online platform GitHub, which first appeared in 2008 and combines a version control system, meticulously maintaining a history of code changes (git), with social networking features. This platform constitutes the largest “public” collection of open-source repositories.

Just as an employer can check the profiles of their candidates on Facebook, on GitHub they can examine both quantitative and qualitative characteristics of a candidate developer’s contributions to open source projects through their profile. In this way, proper “self-care” in the form of carefully cultivating a profile on this specialized social networking platform tends to become an absolute “must” for developers (just as Facebook is for everyone), so they can present a “good face” in the increasingly competitive job market. We translate from the conclusions of a relevant study,20 which includes interviews with both employees and employers regarding this issue:

“The type of transparency that GitHub pioneered may have implications for the future of hiring processes. Employers may begin to expect applicants to provide a rich trail of activity history in detailed work. Those seeking employment can in turn increasingly turn to companies that will allow them to develop a publicly-available (or open-source) portfolio of their work. Businesses can see that employees want them to share their work to some extent as open source, and view openness policies as benefits. We already see this trend in fields such as graphic design, as individuals often work for themselves in order to maintain the ability to prominently promote their work.”

And he continues, concluding:

“The impacts of our results extend beyond software development as work becomes increasingly digital. Providing accessible, reliable traces of an individual’s work history can support more accurate representations of unknown factors. These representations will shape decisions regarding recruitment, hiring, and promotions in both traditional and new forms of organizational structures such as Wikipedia and crowdsourcing. Such representations are also likely to influence the collaborative dynamics of work. It is important for system designers and policy makers to study which actions and activities can and should be recorded and remain visible. Our results should help decision makers develop useful and efficient ways to provide various groups with the information they need while protecting individual rights.”

The terms and conditions imposed on labor in an increasingly digital workplace are becoming ever more transparent, ever more “collaborative.” In reality, openness is promoted as a manifestation of the value of cooperation, which, as it becomes personalized and quantified, generates multiple benefits and, of course, profits for employers. Things seem to be getting worse for young “digitally employed” workers. Perhaps the only thing that may remain, as a last lie, for those unwilling to enter such a regime of transparency, is an illusion of maintaining their virtual status in the labor market. This is the illusion of ownership/private use of open—more than ever before—digital media of production, as micro-entrepreneurship: a startup here, an individual business (an office or freelancer) there, a job with-my-friends-who-are-also-at-the-same-stage a little further on. So long!

concentration: material, software and data as capital

As an irony for the history of free software, the largest investments by technology giant corporations in recent years concern the development of “cloud” and “big data” technologies that are based on open source software. In September 2013, IBM announced a business plan for “investing 1 billion dollars in Linux and open source innovations”. According to the company’s press release:

“The investment aims to help our customers capitalize on big data and cloud computing technologies with modern systems designed to manage the new wave of applications coming to data centers in the post-PC era.”

In May 2014, a similar announcement for “investments exceeding 1 billion dollars in open-source cloud-computing” was also made by Hewlett-Packard.

At the same time, strategic planning regarding cloud computing does not escape the central designs of states. The European Union, within the framework of the “single digital market” adopted in May 2015, includes among other initiatives the “European Cloud Initiative” as a continuation of the implementation of the “European Cloud Computing Strategy” announced in September 2012, while the US had already formulated their own “Federal Cloud Computing Strategy” from February 2011. And these central state strategies do not fail to give due importance to “open source data analysis tools”.

Christopher Kelty, the author of the book that gave us the impetus for this tribute, in an article he wrote in July 2013 with the heavy title “There is no free software”, writes,21 with admitted bitterness and disappointment, something like an epitaph for free software. If the crack of transcending intellectual property in code has been “plugged” by creating new forms of ownership over data, how are these now shaped? Kelty, towards the end of his article, makes the following observations:

“The current success of the ‘cloud’ has to do more specifically with the material transformation of the Internet from a heterogeneous ecosystem of small and medium-sized nodes (simple servers and small server arrays) into a handful of massive data centers and server farms running virtual versions of the Internet within them. The largest of these facilities, such as those of Google, Amazon, or Rackspace, all run ‘open source’ software—but the concept makes less and less sense as these systems become larger and more controlled. If the critical power of open source had to do with its openness, its general capabilities, and its modifiability, then the anti-critical force is simply monopoly: control over all servers, which, even if they run open source software, do so only for the sake of sovereignty…

In the realm of consumer products, a similar change has occurred: what difference does it make if iTunes or the Android Marketplace run on free software? … Now we must submit to the sovereignty of Apple to play (or Google or Amazon). Some of the most devoted supporters of free software may shed a tear or two when contemplating this situation, but 99% increasingly find no personal or political issue with it—and perhaps they are right, perhaps the matter is overly academic… The point is that free software cannot maintain its recursive public character in these spaces—that the fragile critical force it once had evaporates in the heat of massively centralized data centers, dissolving into the frenzied and futile need for our devices to operate at all times…”

…

Whether we like it or not, every touch, every click, generates data that ‘goes up’ and is stored in a data center somewhere on the planet, in the ‘cloud,’ analyzed as ‘big data,’ turned into a product, sold, bought; sometimes we learn that we too have added our grain of sand to the export of today’s, weekly, monthly, or annual trends of the internet. This is how every click, every touch—once the finger is lifted and the result falls into the ownership of company X or Y as data—’ascends’ and functions as absolute good or absolute evil; freedom is out of the question. So if free software died as open source, then long live ‘open data!’?

Kelty himself closes his article by writing:

…

“We need an analysis that gives us the concepts with which we will understand what this industry and its facilities do in the world; as it concentrates and re-transforms into a monopoly for the nth time in equal decades; as it becomes increasingly indistinguishable from the world perceptible to us; as it turns programmers and system administrators who until recently exercised criticism into silenced employees; as … it diverts money and time … as it creates within itself the very tools for its analysis, transformation and reconstruction.”

There is no free software. And the problem it solved is still here.”

Or perhaps the issue of the existence or not of free software has become – by now – simply secondary…

Program Error

- For more information regarding the concept of “open”, its contributions and variations: Tkacz, Nathaniel. (2012) From open source to open government : a critique of open politics. Ephemera: Theory and Politics in Organization, Vol.12 (No.4). pp. 386-405.

Available at: http://www.ephemerajournal.org/contribution/open-source-open-government-critique-open-politics-0. ↩︎ - Two Bits: The Cultural Significance of Free Software (Duke University Press, 2008) by Christopher M. Kelty. Available at: http://twobits.net/pub/Kelty-TwoBits.pdf ↩︎

- The author’s notes are not transferred/translated here. The references in the section below constitute translator’s notes (StM), which sometimes summarize the notes of the original text or/and add additional information related to the content. ↩︎

- (S.a.) The term “source code” refers to the sequence of programming instructions written in a human-readable programming language. In order to run on a computing machine, the source code can be converted by another program, called a compiler, into executable machine code. ↩︎

- (F.N.) The dispute between advocates of one or the other concept (free software or open source) can be explored on numerous websites, forums, mailing lists, etc. For anyone interested, they may refer (to begin with…) to the following links, which originate from corresponding “central” organizations that have been created:

– http://www.gnu.org/philosophy/free-software-for-freedom.html

– http://www.opensource.org/history

– http://www.gnu.org/philosophy/free-sw.html

– http://www.gnu.org/philosophy/words-to-avoid.html

– https://opensource.org/osd-annotated

It should also be noted that today the hybrid terms FOSS and FLOSS are widely used:

– https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alternative_terms_for_free_software ↩︎ (Σ.τ.μ.) In 1983, Richard Stallman announced his plan to create the GNU OS, as part of the Free Software Movement (FSM). GNU (an acronym for “GNU’s Not Unix”) is part of today’s GNU/Linux operating system (this is its full name). The GNU OS was to be written from scratch without containing any proprietary code at all. In 1985, Stallman founded the non-profit organization Free Software Foundation. The most significant development of that period was the drafting of several individual copyright-style licenses which, although based on the legal framework of intellectual property rights, were designed to prevent intellectual ownership of code produced within the FSM. In a way, they used the copyright mechanism against itself by stating in their text what should be allowed rather than what should be forbidden. In 1989, Stallman developed the first version of the GNU General Public License (GNU GPL), which was designed to replace the previous individual anti-copyright licenses and to spread like a virus. The GNU GPL was the most progressive of its kind: for any piece of software code written under this license, access to it, copying, modification, and redistribution (with or without charge) should be permitted, but the same must also be allowed for any future program that incorporates software components released under the GNU GPL license. Today, this license, whose type is also referred to as copyleft, is in its third version (3.0): http://www.gnu.org/licenses/gpl-3.0.html. Each new version of the GNU GPL attempts to close potential “loopholes” for the simultaneous use of proprietary software components within the same product, which through their copyright licenses effectively nullify its content. Meanwhile, there have been losses: the Linux kernel, for example, did not adopt version 3.0 and remained on version 2.0.

↩︎- (Ed.) Access to the Internet via a browser is based on the client-server model. Generally speaking, the browser (on the PC, laptop, tablet, or mobile device) acts as a client that sends a request to a remote server (somewhere on the Internet), which fulfills it and returns a response. While the browser is not functionally involved in the actual processing of the request by the server, it must be able to understand the response that comes back so that it can, for example, display a webpage. This is where specific, standardized protocols should be used, so that any server can work with any client. ↩︎

- On Wikipedia there is a comparative table with the characteristics of various free software and open source licenses:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Comparison_of_free_and_open-source_software_licenses ↩︎ - To avoid misunderstandings: the high sociality of work today is not a peculiarity of the information and communication technologies sector, but concerns the entirety of capitalist production. Can one really conceive, even for the simplest thing (say, a bottle or a glass), through how many hands and how many minds it passes before reaching his/her hands? Even a relatively loose attempt to describe this journey could fill the pages of a small book. Interdependence and cooperation, as characteristics of global work, for apparently simpler things than software, seem really difficult to grasp directly, let alone describe in detail. And yet, here too, the development of productive forces, including new technologies, holds a central position. Although this is not exactly our topic, we can accept the argument that software is an “easy” case, however mythologized for its uniqueness in the sociality, participation, and cooperation of workers during its production. ↩︎

- Only in this way can the productive forces themselves, which develop and appear to surpass here or there the very necessity of the existence of the owners’ class, ultimately recognize in the existence of capital their only feasible form of collectivity/communality; since this communality at its base – living labor – is fragmented, weakened, undervalued, individualized, and finally accumulated as wealth in the hands of the owners’ class. The “Here or There” of this surpassing, insofar as it becomes self-referential (and this often occurs in the case of software) and does not acknowledge these processes of the crisis of property relations, of devaluation, subordination, and accumulation as processes that take place and apply to the entirety of global production (and global labor), signifies something more: The clicking of a button as a possibility (or/and freedom) Here may simultaneously coincide with the death of some Others There; and it is as if nothing is happening. ↩︎

- Related readings, for p2p:

-Bawens, M. (2005). The political economy of peer production, Ctheory.net

Available at: http://www.ctheory.net/articles.aspx?id=499

-Benckler, M, Nissenbaum, H. (2006). Commons-Based Peer Production and Virtue, 14(4) J. Political Philosophy 394-419. Available at:

http://www.nyu.edu/projects/nissenbaum/papers/jopp_235.pdf ↩︎ - With a (perhaps) exaggerated dose: The keyboard somehow transforms for many of them into a “consumable” and is replaced just as regularly, with the printer’s inks. With the assumption that the former is becoming more and more frequent while the latter is becoming increasingly rare. Only a few “old-timers” now systematically type on paper. ↩︎

- The term could refer to the “burning” of developers. However, here we are referring to charts that represent the actual progress of a project (burndown charts), which describe the degree of completion of sub-tasks, and which are issued in comparison to an ideal progress path. Managers make sure that the “ideal” progress path serves as the carrot of the matter; and the whip, of course, is their own. ↩︎

- The formation of such “communities” often arises from the programmers of a company themselves as a reaction when the company tries to “close” the software code with copyright. It is most often accompanied by the establishment of “non-profit organizations” which are frequently sponsored by competitors of the first company. For more information and examples regarding such cases: Birkinbine, Benjamin J.. Conflict in the Commons: Towards a Political Economy of Corporate Involvement in Free and Open Source Software. The Political Economy of Communication, [S.l.], v. 2, n. 2, feb. 2015.

Available at: http://www.polecom.org/index.php/polecom/article/view/35 ↩︎ - Red Hat, possibly unknown to home PC users, holds a significant share in the operating systems market for servers. ↩︎

- The billiard and ping-pong tables, gyms, lounges and social spaces at the campuses of the big ‘classic’ IT companies, on one hand aim to extend the working day. On the other hand they try to simulate “community” conditions (perhaps even…), but these don’t seem to suffice as “innovations”. The average salary at these companies remains relatively high, while their market share is decreasing. Perhaps this is the reason that even Microsoft is turning, belatedly admittedly, but with increasing dynamism towards open source; despite the fact that Bill Gates himself had accused, as recently as 2005 in an interview, open source communities as a “new dangerous form of communism”(!) ↩︎

- Referring to the entire scope of the dedication to programmers or developers does not mean that we ignore the existence of other types of work within IT companies, which, among other things, are necessary for developers to do their jobs. We use this figure more schematically since we are talking about software. The conclusions, as we will see below, can concern broader segments of what we prefer to call the “electronic proletariat” and not only the classic (usually white and male, although this is tending to change – another topic) figures of programmers. ↩︎

- At this point, much could be said about the practices that led to what is called “piracy”; about cracked programs, digital sharing of music, movies, books… Practices that, in their own way, turned against intellectual property and changed the landscape and scope of internet usage. Today, subscription services such as Netflix (for movies) or Spotify (for music) owe their existence, among other things, to these practices. Their creation represents the most serious solution so far, whereby, through the ease they offer in usage, payment of intellectual rights becomes widely acceptable again via subscription. Moreover, the general trend even in proprietary software (which is opposed to “cracked” versions) is to be provided as a subscription-based online service, as a significant portion of program installation and execution is transferred from home PCs to the “cloud”, namely to large-scale computing facilities under the company’s control. Characteristic examples are the latest product packages from Adobe as well as many popular online games. ↩︎

- Peter Naur and Brian Randell, eds., Software Engineering: Report on a Conference Sponsored by the NATO Science Committee, Garmisch, Germany, 7th to 11th October 1968 (Brussels: Science Affairs Division, NATO, 1969). ↩︎

- Marlow, J. & Dabbish, L. (2013). Activity traces and signals in software developer recruitment and hiring. In Proceedings of CSCW, 145–156.

Available at: http://www.cs.cmu.edu/~xia/resources/Documents/Marlow-cscw13.pdf ↩︎ - Kelty, C. M. (2013b). “There is no free software.” Journal of Peer Production, 1(3)

Available at:

http://peerproduction.net/issues/issue-3-free-software-epistemics/debate/there-is-no-free-software/ ↩︎