Morpheus: Let me tell you why you’re here. You’re here because you know something. What you know you can’t explain, but you feel it. You’ve felt it your entire life, that there’s something wrong with the world. You don’t know what it is, but it’s there, like a splinter in your mind, driving you mad. It is this feeling that has brought you to me. Do you know what I’m talking about?

Neo: The Matrix.

Morpheus: Do you want to know what it is?

Neo: Yes.

Morpheus: The Matrix is everywhere. It is all around us. Even now, in this very room. You can see it when you look out your window or when you turn on your television. You can feel it when you go to work… when you go to church… when you pay your taxes. It is the world that has been pulled over your eyes to blind you from the truth.

Neo: What truth?

Morpheus: That you are a slave, Neo. Like everyone else you were born into bondage. Into a prison that you cannot taste or see or touch. A prison for your mind.

This is the dialogue, from 17 years ago, that introduced cinema audiences to the concept of the matrix and subsequently established it as an inseparable and highly meaningful element of contemporary mass culture. It was 1999, and that spring the Wachowski siblings’ film titled The Matrix was released in theaters. The film was a tremendous box office success (and continues to this day to generate profits for its producers), created a huge sensation among both cinephiles and non-cinephiles alike (a sensation that has grown over the years, something not so common for a blockbuster), and was considered highly radical and subversive based on its content.1 Let us note in advance: the film continues to this day to be classified among the highly politicized films within the spectrum of “resistance” – but not for us! We categorize The Matrix as controversial, if not reactionary,2 although this is not the main reason we are discussing it. We are concerned with it because it constituted (along with its two sequels from 2003) something of a trailer for the soaring bioinformatics paradigm of our time, a kind of advertising campaign in favor of universal digitization.

Typically, it belongs to the genre of science fiction adventure, and its main themes are, on one hand, the overplayed war between humans and machines, and on the other, the existence of a second reality, parallel to the authentic one and dominant over it, virtual and electronically generated. Although it was not the only notable film of that era with a similar theme (examples being Dark City and The Truman Show of ’98 and eXistenZ of ’99), it was nevertheless the only one to become so identified with the concept of virtual reality that it is rightfully considered a landmark film of the modern digital age and a cinematic manifesto on the possibility of total social control through technology.

The plot follows the (almost hagiographic) journey of Thomas Anderson from ignorance and doubt to enlightenment and from there to crusade (in the struggle “for the liberation of humanity”). The hero is an ordinary employee at a large computer company, who simultaneously lives a “second life” as a hacker with the pseudonym Neo (a corruption of the Greek “Νέος” and an anagram of the English “One”). Due to his online activities, he risks being arrested by the (particularly skilled) agents of some unspecified service, but is saved at the last moment thanks to the intervention of a famous hacker, Morpheus, and a mysterious woman, Trinity.

Morpheus is the one who reveals to Neo the terrible reality. That at some indefinite moment in the past, the creation of artificial intelligence led to the war between humans and machines, the destruction of the environment and the victory of sentient machines. Humans are now slaves who are not born but cultivated and maintained in tanks so that machines can exploit the energy produced by the human body. To maintain the sedation and control of humans, machines keep them permanently connected to an advanced virtual reality system, the matrix, which represents social life as it was in 1999, while only a few have managed to escape and live in the constantly threatened “last city of humans”, Zion. Morpheus reveals the existence of a “prophecy” that foretells the coming of a “chosen one”, Neo in this case, who will have the ability to transform the matrix as he sees fit and will put an end to the dominance of machines.

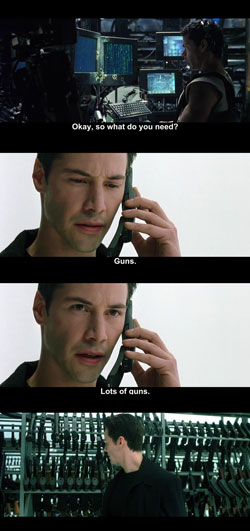

When they visit the “prophet” so that he can check whether Neo is truly “the chosen one,” one of Morpheus’s crew betrays them to the agents, who are in reality intelligent security programs of the matrix, resulting in Neo’s capture and threatening the very existence of the “resistance” and Zion. Neo then, gradually realizing his role as “the chosen one,” organizes a daring rescue operation within the matrix, where he must confront the agents and especially his deadly enemy, Agent Smith. He manages to free Morpheus, but in his confrontation with Smith, always within the matrix, he is fatally shot, dies equally in real life, but is ultimately “resurrected” with Trinity’s help. In the end, he neutralizes Agent Smith (literally assimilating him within the matrix’s programming environment) and now acquires the full range of abilities that the “prophecy” had attributed to him.

The movie closes with a “war declaration” that Neo addresses to the machines as he himself takes off and flies through the matrix to the sounds of Killing in the name by Rage against the machine…

an astounding compendium

(or otherwise: a visual potpourri of religion, philosophy and politics)

The Matrix is certainly not a masterpiece, even by elastic artistic criteria, nor can it be considered, even in spirit, equivalent or even related to films such as 2001: A Space Odyssey, despite its devoted admirers. Nevertheless, it has displayed an impressive and enduring penetration into a diverse, even radically opposing, array of societies. Undoubtedly, the timing of the film’s release played its part. The year 1999 was the psychological threshold between the trivial “old” and the exciting “modern” that every 20th-century futuristic narrative had promised. It was the year when the first mass fear erupted regarding the internet and information technology, triggered by the “Y2K bug” and the threat of an imminent collapse of electronic networks. The new bio-informational paradigm was by then sufficiently mature, yet not yet socially entrenched; the explosion of social media, smart devices, and generalized digital mediation was still forthcoming, though not absent. The Matrix managed to capture the spirit—granted, in an excessively loud manner—of universal digitization and fit so perfectly with that era that it is reasonable to wonder whether the film merely captured existing trends or acted as a kind of trial test for a pre-designed direction, in order to gauge attitudes and reactions.

One reason that explains the film’s impact has to do purely with its cinematic characteristics. The meticulous direction of a fantastical spectacle, with epic choreography-like action scenes and a barrage of special effects (groundbreaking for their time and technologically innovative) acted as a sensory flash in the eyes of viewers, “revitalized the sci-fi genre” according to cinephile argot, and set new standards in film productions.

But even more so, it measured the very content of the film and the development of it as a complex mosaic of religious, philosophical, and political references. The semiotics of Judeo-Christianity, messianism, Hinduism, Buddhism, Gnosticism, and syncretism run throughout the film, equally convincing believers of different religions that the film constitutes a (post)modern cinematic metaphor for their doctrine. For example, the imagery of the “trinity,” “prophecy,” the anticipated arrival of the “chosen one,” his “sacrifice” and “resurrection” requires no particular interpretation as to what it alludes to. At a philosophical level, it has been argued that the film is nothing less than a metaphor for the Cartesian hypothesis of the evil demon, that is, that the perceived reality might be the result of an illusion constructed by some malicious spirit in order to deceive us. Or a metaphor for Plato’s Allegory of the Cave, with a group of people living chained in the depths of a cave, constantly staring at the wall and perceiving reality only through shadows. Or a metaphor for the more modern hypothetical experiment of the brain in a vat (a living brain maintained in a vat, with all its sensory stimuli originating from a computer). Equally confidently, it has been argued that the entire film is imbued with Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason, especially regarding the difficulty of distinguishing between truth and false perceptions.

The work Simulacres et Simulation of 1981 (with which the French Jean Baudrillard argues that contemporary social reality has been so symbolized that every meaning has been eroded and human experience has fallen into a simulation of reality) has been considered the main source of inspiration for the matrix, although Baudrillard himself has argued that the film misunderstands and distorts his work. From Simulacres and Simulation, moreover, comes the most famous quote of the film: welcome to the desert of the real (which had long since become caramel in every kind of political text). And because Baudrillard had in turn based himself (and distorted) Society of the Spectacle, the situational references are obvious, equally with Marxist, anarchist, even Situationist signifying elements that are scattered throughout the film. Equally emphatic are the references to Alice in Wonderland, to the artistic work of Escher, to Metropolis, to Greek mythology, to conspiracy theories, and to cyber-punk literature (particularly Gibson’s Neuromancer, which the filmmakers have plundered and abused).

The mobilization of such an eclectic and contradictory repertoire of references and allusions upon everything conceivable did not, as fans of the relevant mythology might wish to believe, result in the production of a coherent cinematic manifesto. Elementary: if you mix prophecies about the chosen one and Buddhist monks who bend spoons together with critique of spectacle and rebellion against the universal panopticon, what you’re cooking up is confusion, no matter how many digital martial arts battles are added to the recipe. The Matrix doesn’t serve enlightenment, but pseudo-intellectualism. The mysticism of religious dogmas combined with radical political theories does not lead to some kind of (anyway insane, irrational, and unthinkable) “spiritual upgrade” of the latter, but to the production of pure metaphysics!

But let us not make the mistake of disentangling the film, simply charging it with a Hollywood-style chaos. Because the intellectual and idealistic acrobatics and coups of The Matrix prove, a posteriori, both intentional and accurate. Since the central theme of the plot is technology and the then-forming bioinformatics paradigm, the metaphysical framework surrounding the film manages to shift the subject from the grounded field of critique to the otherworldly sphere of the magical. That, after all, was the film’s success: it was magical! Not in the sense that it offered an excellent spectacle, but because it succeeded in enchanting an extremely political issue such as the generalized digital mediation of social relations. That is also why so many people, from so many different starting points, with so many different orientations, saw so many things in this film. Radical activists, conspiracy theorists, sensitive liberals, opponents of multinational corporations, internet junkies, postmodern believers, enemies of the Antichrist or of globalization, advocates of violent action, products of academic institutions and intellectual stars—all of them considered The Matrix “their own film.” Precisely because it was enchanted, each viewer saw in the film exactly what they wanted to see; and few understood in time exactly what the matrix mythology was truly advocating. Because, on one hand, pseudo-political intellectualism and, on the other, techno-enchantment strip the supposedly subversive meaning of the film bare, revealing its real, pathetic content: The Matrix was an advertisement for digital mediation, not a denunciation of it. We will confirm this by examining specific aspects of the matrix mythology (referring mainly to the namesake film, but also to the two sequels where necessary).

in the world of generalized virtuality, the real is a moment of the fake

The death of history. While dramatic events have occurred and developments of cataclysmic dimensions have preceded, history is involved in the plot only once and there fragmentarily, sibylline, like a simple reference. “We have only pieces and fragments of information” says Morpheus to Neo, at the beginning of his indoctrination, to justify their ignorance.3 Justified, one might say; the human, civilized world has died, the machines are in control and the “resistance” is nothing but a handful of former slaves fighting against terrible adversities.

Correct, but these adversities do not seem to prevent the “free humans” from having increased access to high technology, both inside and outside the matrix, which they obviously steal from the machines, demonstrating high-level abilities in violating strictly guarded systems. Moreover, it is logical that within the matrix itself there would be detailed records of the past, simply because no operating system can function without a detailed log file. Therefore, the ignorance of history that characterizes the protagonists is not a result of their tragic condition, but a deliberate choice of indifference. It is not a technical issue, in the sense that they could – there was a way – but they don’t. It is a political message of devaluing history and is furthermore proven by the spirit that permeates the resistance: the machines are in control – we’re looking for the “chosen one” – he will destroy the matrix. That’s it, everything is played out now! How much more so when it is revealed (in the sequels) that this is the sixth time (!) the matrix-human conflict is repeated and the “arrival of the chosen one.” Thus, the living element of history demonstrates a consistent and conscious effort to act trapped in a perpetual present that extends indefinitely. The historical burden is zero, now is when everything must happen: this is the message of the “resistance.” This type of behavior should not surprise us, nor should we interpret it as radicalism; it is exactly what characterizes modern social networks, relationships that are digitally articulated, and the politics produced by cyberspace: the dictatorship of the urgent and the tyranny of the present – this is the “positive” message that The Matrix prophetically put forward.

Social personality versus digital personality. The basic elements that construct the fabric of the film are a series of bipolar, Manichaean conflicts that are appropriately illuminated so that the “good” and the “bad” sides are completely evident. The most characteristic is the conflict between Neo and Agent Smith: the former wants the liberation of humans, while the latter wants the destruction of their “last city”; the former is human, the latter a program. But if we look carefully, we will discover that their differences are not so extreme—in fact, they resemble each other. Even more so: they identify with each other, since they are essentially the same bio-informatic subject. When Smith interrogates Morpheus, in a moment of sincere confession of the strong versus the weak, he reveals to him what his motives are: “I hate this place… this prison… this reality… whatever you want to call it. I can’t stand it any longer… I have to get out of here. I have to find my freedom.” The voice that delivers this statement may be Smith’s, but this line of thought belongs to Neo and is exactly the description of his own motives that drive him from the beginning. The actions of both converge on the same goal: the breach of the matrix. The unspoken identification of the two “enemies” is also revealed by the way their conflict is resolved. Neither wins, nor do they destroy each other; on the contrary, they merge into a single entity, and with this new form, Neo truly becomes the “chosen one.” We could phrase it differently: the biological self, limited and powerless, acquires enhanced abilities through technology and is transformed into an organic-digital hybrid—a new anthropological type that lives and moves comfortably in both physical space and cyberspace. Here, then, is the true hero of The Matrix.4

Truth against virtual reality. Is it really the case that the film’s narrative illustrates how terrible artificial life in the matrix is and how obviously preferable harsh truth is? Or perhaps, in reality, what it masterfully recounts are the negative consequences of the split between the two levels and the necessity of their organic fusion? Let us examine this, bypassing the easy moral answers the script suggests. Zion, the “last city” of free humans, is presented as the opposite of the matrix. “My brother and I are 100% pure, naturally born humans. We were born free here, in the free world. Genuine children of Zion… If the war ended tomorrow, Zion is the place where the party would be held” boasts proudly one of the members of Morpheus’s group. Beyond references to it, the city itself is portrayed more extensively in the second film. It is located deep underground, its resources are extremely limited, and outside of it, the only area where there is any possibility of movement and action is the network of old sewers of the destroyed cities.

So while life in the “city” is practically that of buried living beings, life in the matrix continues just as it did at the end of the 20th century, with its routine, conveniences, and difficulties. Yes, but one is authentic, genuine – someone well-intentioned would counter – while the other is illusion. If that is so, then Morpheus himself, the “voice of knowledge,” takes care to nullify any differences. “What is ‘real’? How do you define ‘real’? If you’re talking about what you can feel, smell, taste and see, then ‘real’ is simply electrical signals interpreted by your brain” he says at one point to Neo, blurring the boundaries between reality and virtual reality.

Yes, but – he insists, the well-intentioned one – in the matrix people are slaves and blind in their ignorance, while the people of Zion, despite their harsh life, are free and masters of their fate. Really? Because in Zion they may organize terrific parties, but as presented, it’s nothing more than a militaristic micro-society, structured militarily around the threat of attack from the machines, in which a council of authorities exercises power that recalls a gerontocracy or aristocracy. With the exception of the few crews circulating in the sewers and going in and out of the matrix, the majority are confined to a regime of inertia, passivity and fatalism. The comparison with the matrix is overwhelming here. Practically nothing happens in Zion, on the contrary in the digital world all the decisive action takes place and all the developments that matter occur. Correctly – the well-intentioned one continues stubbornly – but that is the price of resistance to the machines and defending their freedom. Freedom? But the highest mission of the “resistance”, beyond the sporadic liberation of individuals from the matrix, is the search for the “chosen one”; the “prophecy” is what gives life breath to Zion and the hope for the coming of the “one”. How much more “freedom” exists in lives ordained by prophecies of fate-sent saviors, compared to lives full of illusions?

Even Trinity, the heroine with incredible abilities who is a notorious hacker and a tough opponent of the agents within the matrix, in real life simply falls in love with “the chosen one” according to what the “prophet” revealed to her.5 What an amazing, feminist approach, of a “free” woman! And at the same time, what an artistic juxtaposition of real life with virtual life: where there is “freedom” there is no life, and where there is “life” there is no freedom. This is essentially what the film supports. Therefore; the answer that is suggestively formulated lies in the abolition of this catastrophic split between literal truth and its virtual version. Since the bioinformatic model is now so powerful and life has become so technologized, then accept virtual reality so as not to end up schizophrenic! Even Baudrillard, whose work so influenced the film, deals with the same issue: the possibility of changing the system from within, without the need for radical upheaval, which he now considers impossible…

preconstructing the “enemy” of the bioinformatics paradigm

Apart from the scattered fragments of criticism of the society of the spectacle appearing in the film, mixed with religious and philosophical beliefs to explain the matrix, the situationists said even more about our time, which the directors, for their own good, carefully avoided. For example, Guy Debord in his book Comments on the Society of the Spectacle, referring to modern democracy, writes the following: “This so perfect democracy constructs its own mysterious enemy… In reality, it prefers to be judged in relation to its enemies rather than in relation to its results.”

This comment, with all necessary reservations, accurately summarizes the essence of the matrix mythology. We could formulate it as follows: the society of generalized computer-mediated communication, after first constructing an image of itself, subsequently constructed an image of an enemy to its measure, so that through the virtual confrontation of the two, a final point of balance would emerge suitable and functional for both supporters and opponents. The cinematic representation of this sequence is exactly the film The Matrix.

The finale of the trilogy (which disappointed its fans, but stayed four years away from the introduction, so as to leave the first film’s brilliance intact) is revealing. The “chosen one” after an odyssey ends up in a truce with the machines, in order to achieve “peace”, under the condition that those humans who choose it will be able to disconnect from the matrix. The regime of slavery remains, but if some slaves wish it, they can leave… Triumph! The matrix remains intact in its position, with some necessary corrections, offering in exchange the provision of fake tickets towards individual salvation. In political terms, we would characterize the whole concept as a process of crisis / restructuring of the system. In football terms, we would say that the match was fixed…

We thus arrive at the point from which we started. Despite the pseudo-political excitement and the thrill of resistance it caused, despite its excessive intellectualism, The Matrix proves to be an extremely controversial and reactionary film. Because it introduces metaphysics into technology and transforms the generalized technologicalization of social relations into a magical ritual and mystical experience. Because it promotes a technological determinism that inevitably and inescapably leads to the dominance of digital and virtual reality, while at the same time downgrading living social relationships to mere accessories-extensions of this virtual reality. Because, finally, it predefines an enemy-caricature of biocomputational integration, made to measure and destined to act only correctively.

The final scene of the movie6 shows Neo sending a message to the machine regime, simultaneously with a promise to the human slaves of the matrix. “I didn’t come here to tell you how it’s going to end. I came here to tell you how it’s going to begin… I’m going to show them a world that you don’t want them to see… A world without you. A world without rules and controls, without borders or boundaries. A world where everything is possible.” It is strange that the bright world promised by the “chosen one” looks so much like the one advertised by the devotees of generalized digital mediation?

Harry Tuttle

- It is impressive the number of studies that have been written attempting to interpret the film from every possible and impossible philosophical, psychological, theological, and political perspective. Ever since its release and up until today, The Matrix has become a kind of case study to such an extent that it is used in humanities schools as a response to the lack of references to classical works that characterizes today’s students. Even the esteemed Slavoj Žižek wrote a book with a title borrowed from the film. We do not know if there are serious people who consider the film to be characterized by rich content, but in any case, it simply reveals to us the boundless intellectual poverty of modern “thinkers”. ↩︎

- The Wachowski siblings have another film that is equally controversial—and in our opinion, extremely reactionary—V for Vendetta. Like The Matrix, V for Vendetta was considered highly politicized, even “anarchic,” and greatly influenced mass culture, with various organizations adopting the film’s symbols wholeheartedly in their mobilizations (let them beware!). The Wachowski siblings had designed the entire concept, wrote the screenplay, and produced the film, while the directing was done by one of their close collaborators. ↩︎

- Only in the movie Animatrix (2003), a collection of nine short animations that complemented the Matrix trilogy, is a more extensive reference made to the infamous human-machine war. There, some interesting elements are revealed that could somewhat shake the image most viewers had formed about the war. In two stories (The Second Renaissance, 1 & 2), the robots are presented as a new slave caste, while humans are immersed in decadence and arrogance. After an “owner” is murdered by his own robot, a pogrom of humans against robots begins, where the former are described in typical fascist mob terms. The remaining robots flee to the desert, build their own city, and manage to establish a thriving economy. In the proposals they make for peaceful coexistence and “symbiosis” with the human race, governments, through the UN, respond with the exclusion of the robot city and ultimately with its nuclear bombardment. In the war that erupts, it is the humans who destroy the sky, in order to deprive the robots of the necessary solar energy, and then is when the latter resort to the solution of converting human bodies into energy generators.

In these two stories, it is worth noting that when the pogrom against the robots begins, they are not alone, but have alongside them a group of humans, the more “progressive” and “sensitized” schematically, who raise the issue of recognizing robots and their rights as living beings. It is not invalid to think that some kind of alliance between robots and (some) humans was more than likely – even more so when the attacking humans display fascist behaviors. Such a possibility overturns the image of a “war of the machines” exclusively against all humans indiscriminately and creates suspicions as to whether the matrix was ultimately a cunning plan of the machines or the result of the alliance and common plans of robots and humans. ↩︎ - A second “conflict” with similar characteristics is that between the “Architect” and the “Oracle” that unfolds in the third film. The “architect,” who is the central program of the Matrix, appears in the form of a condescending yet omniscient, white-bearded elderly man, immediately evoking the image of God. The “oracle,” who appears as a sweet maternal figure in the likeness of a saint (she even bakes cookies for her believers!) and throughout the entire trilogy plays the role of the spiritual leader of the “resistance,” is ultimately revealed to be a program—and indeed one of the fundamental ones within the Matrix. The architect’s purpose is design, while the oracle’s is understanding. The entire story of the trilogy is ultimately revealed as the “conflict” (in programming terms) between these two programs over which strategy is more suitable in order to prevent the collapse of the Matrix: the architect insists on adhering to the original programming, while the oracle seeks to “upgrade” humanity’s role. The heroes are ultimately revealed to be acting under the oracle’s influence, and the entire epic of the “resistance” and the “liberation of humanity” collapses into a mere reorganization within the technological apparatus. ↩︎

- Besides Trinity, a mention is equally deserved by another protagonist, the villain Cypher, who is the one betraying the protagonists to the agents. He is another figure appearing through a distorting mirror: he seems possessed by motives opposite to the noble ones of the others, but ultimately proves to be the most consistent and grounded in reality. To begin with, the audience should applaud him, since he is the only one explicitly questioning the “prophecy” and calling the “chosen one” mind crap; ultimately, he is vindicated. In the scene where he betrays his companions, he is together with agents in a (virtual) luxury restaurant, enjoying a steak (while in normal reality he is fed a standardized gruel), and as he haggles for the exchange he says the following: “I know that this steak doesn’t exist. I know that when I put it in my mouth, the matrix tells my brain that it’s juicy and delicious. After nine years, you know what I realize? That ignorance is bliss!”

At least he acknowledges that he is immersed in ignorance and accepts it; the others believe in the illusion that they are serving a higher purpose. In the finale, the price he asks for is to be reinserted into the matrix and have all memories erased from what he experienced outside, while he was a member of the “resistance.” That is, he claims – for himself, personally and at the expense of the others – that towards which the entire trilogy converges: a negotiation for a new symbiotic relationship between virtual and genuine reality. Certainly Cypher is cynical, but a thousand times preferable is cynicism to the idealism that leads to exactly the same results… ↩︎ - At the beginning of the movie, there is a highly ironic scene. Neo, still as Thomas Anderson, arrives late for work before coming into contact with Morpheus and the resistance, and his boss reprimands him. “You have a problem with authority, Mr. Anderson. You believe you’re special, that the rules don’t apply to you. Obviously, you are mistaken” his boss tells him sternly. This scene foreshadows Neo’s future, the “chosen one” who will be able to violate the rules of the matrix at will, but at the same time it also foreshadows the ending. That he is “mistaken”, that he remains inescapably dependent on the system… ↩︎