The belief that in this glossy era of technology and innovation, production has changed form and become immaterial, is dominant in the minds of first-world citizens. Equally dominant is the belief that the working class has absolutely no relation to scientific and technological progress. These impressions have as their reference point the flourishing of the services sector and the transformation of production methods in factories in the capitalist “developed” world. The above constitute fundamental transformations that occurred from the 1970s onwards, as consequences of the refusals of industrial workers against the Fordist model of production. In this context, opinions have been formulated that place at the center of these transformations the production of digital commodities and often conclude that work and its results have now taken immaterial forms:

“The concept of immaterial labor is defined as the labor that produces the informational and cultural content of the commodity. On the one hand, regarding the “informational content” of the commodity, it refers directly to the changes taking place in the labor process in large enterprises in the industrial and tertiary sectors, where the skills involved in direct labor are increasingly skills involving governance and computational control. On the other hand, with regard to the activity that produces the “cultural” content, immaterial labor includes a series of activities that normally are not recognized as “work”—in other words, the kinds of activity involved in defining and shaping cultural and artistic standards, fashion, tastes, consumer norms and, more strategically, public opinion.

Lazzarato, M. (1996). Immaterial Labor

…

The great transformation that began in the 1970s has changed the terms in which the question is posed. Manual labor increasingly includes processes that could be considered “intellectual,” and new communication technologies require subjectivities that are increasingly rich in knowledge.”

Lazzarato is obviously trying to introduce a neologism, while he could have sufficed with the term intellectual labor to describe the production of digital commodities. The misleading dimension of his originality lies in the unilateral and detached perception of “digital production” as exclusively central to contemporary production. What those who easily use this neologism fail to acknowledge is that one of the most central transformations that occurred in the post-70s era was the transfer of a large part of heavy industry to countries in Asia mainly, but also in Africa. What is also omitted is that in order for the production of all these digital/cultural commodities to be feasible, raw materials are required; and these must be extracted from somewhere. What ultimately happens when the allegedly “immaterial labor” that produces “immaterial products” itself requires as a precondition the production and use of material technical means? Where and how are these produced?

the components of technological magic

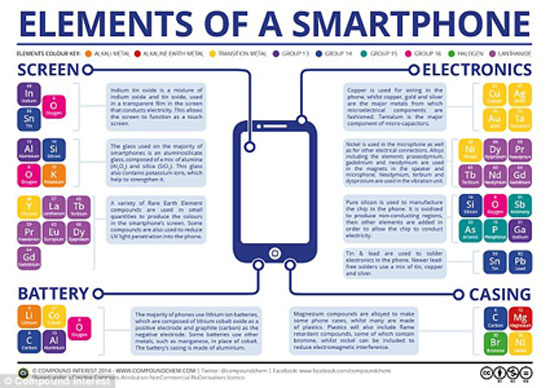

What then is it that makes up a smartphone, a tablet, a computer? Is it the conception of the idea, the design? This might be the main work of engineers in Silicon Valley, but such a thing alone is not enough to bring a technological product to store shelves. Could it be the software, the operating system, the applications that make up technological products? These are important too, but beforehand something must exist in order to be programmed. Programs need the existence of a processor, memory and often a hard drive in order to run. All these physical parts that constitute a computer are called hardware. If you take a look inside a computer or any other electronic device, you will find microchips, various ports, circuit boards, cables, a power supply or a battery and hundreds of other small components such as resistors, capacitors, transistors, diodes, LEDs, etc.

However, there are also other components that make up technological “miracles.” The “zero point” is nothing other than the mining of minerals, mainly from mines located in Africa, Asia, and South America. A brief list of some of the component elements of electronic products includes the following: gold, copper, aluminum, silver, silicon, cobalt, tin, tungsten, tantalum, beryllium, gallium, indium, neodymium, palladium, yttrium, dysprosium. For a smartphone, it is estimated that 40-60 elements are used. As the capabilities of mobile phones increase, the number of necessary elements increases significantly. Many of these are rare earths.1

If you look into the mining history of each of the components of a technological product, you certainly won’t find any pleasant fairy tale. Here we will refer only to some of them. Note the ways they are used by the electronics industry:

– Tin is essential for soldering electronic circuits.

– Tungsten, due to its very high density, allows the production of small-sized components responsible for the vibration of mobile phones.

– Tantalum, which is extracted from the mineral coltan, is an important metal for electrical energy storage. It is used to make tantalum capacitors, which are essential elements in the production of electronic devices, as they can store electrical energy at high temperatures. This property makes tantalum capacitors very important for minimizing the size of mobile phones and other wireless devices.

– Gold has high conductivity and is particularly used for transferring low-intensity current with high reliability. That’s why it is used for the interfaces and connections of small electronic components.

– Cobalt is a component of crucial importance for the lithium-ion rechargeable batteries used in cameras, laptops, mobile phones, and other portable devices. It is also used for many industrial and military applications.

– Indium makes touch screens possible, while a variety of other rare earths are responsible for screen colors.2

The first stage in creating an electronic product is therefore located in a mine. Subsequently, the minerals are sold to smelters for metal extraction. The metals are sold to manufacturers who produce individual components, which in turn are purchased by factories that undertake their assembly.

Let’s take the story of manufacturing a technological product from the beginning. And let’s see, as it takes shape, what happens in some of the parts that are crucial for the production of electronics.

Democratic Republic of the Congo

“Tungsten, tin, tantalum, and gold – products commonly used in the production of electronic goods and known as the ‘3TGs’ – are intensively mined in the Democratic Republic of Congo and other central African countries. Revenues from certain mines are used to fund an ongoing war that has become the deadliest armed conflict since World War II.”

Time Magazine, There May Be Conflict Minerals in Your Smartphone, June 3, 2014

Between 1885 and 1908, the King of Belgium, Leopold II, incorporated the Congo into his personal estate and gave it the name “Congo Free State.” Leopold acquired the region to carry out a “humanitarian” and “philanthropic” mission with the approval and support of the European community. The inhabitants of the Congo were enslaved by the regime and produced mainly ivory and rubber, whose demand and price had skyrocketed during that period due to the invention that led to the extensive use of tires on wheels (for bicycles and subsequently for automobiles). The communities of the Congo were forced to produce and deliver specified quantities of rubber and ivory to officials. Leopold’s private army imposed forced labor and ensured production. The failure of slaves to deliver the specified quantities was punished by death and mutilations. There is no exact number of how many Congolese were killed during that two-decade period. It is estimated that it ranged from 10 million to half the population of the Congo.

From 1908 to 1960, Congo became an official colony of the Belgian state under the name “Belgian Congo” and subsequently went through wars and dictatorship. In the more recent history of today’s Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), conflicts and war with neighboring states led to 5.4 million deaths from 1998 to 2007.3

The paragraph below refers to the article Congo’s Tin Soldiers by journalist Jonathan Miller, published in 2005.4

“Jonathan Miller, a reporter from Britain’s Channel 4, widely broadcast the grim account of coltan exploitation in the interview he conducted with Muhanga Kawaya, a miner from the remote northeastern region of North Kivu province in the DRC, who said: ‘As you crawl through the tiny hole, scraping with your hands and fingers, there’s not enough room to dig properly and you get scraped badly all over your body. And then, when you finally do come out with the cassiterite, soldiers are waiting to snatch it from you at gunpoint. Which means you have nothing to buy food with. Therefore, we are always hungry.’ The soldiers referred to by Kawaya are armed rebels from Congo and Rwanda who continue to profit from the illegal coltan trade.”

The mineral-rich areas continue to be a field of operation for many armed groups, some of which are actively supported by neighboring countries (Rwanda and Uganda) that have alliances with other major powers, mafias, and companies.

The widespread violence and control of mines and mineral trade by armed gangs ensures the mobilization of labor for the mines, which, with a gun to their head, remains disciplined and cheap. The illicit trade in minerals funds the activities of private armies. Thus, mining is secured and mineral prices are kept low, a fact particularly “convenient” for the companies and states that use minerals produced in Congo as raw materials.5 The era when Leopold violently seized rubber—in many respects—is not very different.

The British newspaper Independent in 2008 published an article titled “How we fuel Africa’s bloodiest war” by journalist Johann Hari, who writes the following:

“The UN concluded that it was a war led by ‘company armies’ who wanted to seize the metals, thanks to which our 21st century society can communicate. The war in Congo is a war for you.

Every day I think of the people I met in the war zones of eastern Congo when I was reporting from there. The hospital wards were full of women who had been raped by armed gangs and had been shot in their genital organs. The children’s battalions – drugged, dazed 13-year-olds who had been forced to kill members of their own families, so that they would not try to escape and return home.”

Among the minerals extracted from the mines of the Congo is cobalt. More than half of the total amount of cobalt produced globally comes from the Congo, mainly from the Katanga region, where the largest mines are located.

In January 2016, Amnesty International published a press release regarding child labor exploited by some of the most well-known electronics companies for the production of mobile phones. For a few days, the media were filled with moving articles about this revelation. No one expected such practices from companies that symbolize development and progress… Child labor! We were shocked!

Amnesty International’s research resulted in an extensive report entitled “This Is What We Die For: Human Rights Abuses in the Democratic Republic of the Congo Power the Global Trade in Cobalt.” Below, we translate some excerpts from the presentation of the report.6

Amnesty International’s research uses investor archives to show how the company Huayou Cobalt and its subsidiary Congo Dongfang Mining (CDM) process cobalt before selling it to three industries that produce battery components in China and South Korea. In turn, these sell the components to battery manufacturers who supply automotive and technology companies, including Apple, Microsoft, Samsung, Sony, Daimler and Volkswagen.

Fatal mines and child labor

[…] Miners working in areas from which CDM purchases cobalt face the risk of long-term health damage and high risks of fatal accidents. At least 80 miners died underground in southern DRC between September 2014 and December 2015 alone. The true picture is unknown, as many accidents remain unrecorded and bodies remain buried in the rubble.

Amnesty International researchers have also found that the majority of miners spend many hours daily working with cobalt without the most basic protective equipment, such as gloves, work clothes, or masks that protect against lung or skin diseases.

Children told Amnesty International that they worked up to 12 hours each day in the mines, carrying heavy loads to earn one or two dollars per day. In 2014, approximately 40,000 children worked in mines in southern DRC, many of them extracting cobalt, according to UNICEF.

Paul, a 14-year-old orphan, began working in mining at the age of 12. He told researchers that the prolonged time underground left him permanently ill:

“I would spend 24 hours underground in the tunnels. I would arrive in the morning and leave the next morning […]”

Violence and exploitation have been an ongoing issue for many decades now in the Congo. Numerous times over the past at least 10 years, investigations and publications have emerged—as revelations of a dire situation or as scandals—regarding the ways large corporations and “Western civilization” benefit from the exploitation of Congolese people. For a period of a few days, disapproving articles appear in newspapers. Perhaps some actions are also taken for appearances’ sake by governments, such as for example the regulation enacted in 2012 in the U.S., under the “Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act,” which requires electronics companies to verify and disclose the sources of minerals from areas where armed conflicts occur (“conflict minerals”) originating from the Congo or neighboring countries, for “consumer protection.”7

Various NGOs and other organizations demand conflict-free and child labor-free products, calling on companies to help limit hostilities and embargo illegal mineral suppliers. But the issue is not conflict-free electronics—something almost like sugar-free gum, in the perception of the cosmopolitan elites. The real issue (it should be…) is Western imperialism and the consequences of capitalism’s totalitarian violence against the global working class. The rest is simply a farce: consumers might protest, in a friendly tone: “we love you, we appreciate you, but do something yourselves too.” Companies in turn will “try to help, but unfortunately things are difficult.” And the final conclusion will always be of the type: “look how those poor (uncivilized for racists) Africans are, they even make children work. That’s just how it is there, poverty!”

However, neither capitalist violence nor Western imperialism are issues that can be addressed by consumers, journalists, and international humanitarian organizations. If that were the case, with so many investigations and related publications, things would have changed by now. In reality, the encroachment of capitalist interests and the plundering of the lives of the most undervalued proletarians are issues that have always concerned the global working class. As long as such a prospect does not appear on the current (at least near) horizon, more sensitive consumers will continue to lament.

indonesia

The island of Bangka has been associated with tin since the 17th century, when Dutch colonialists began moving Chinese workers there to mine the metal. Today, one third of the world’s tin production comes from the neighboring Indonesian islands of Bangka and Belitung.

According to the local government’s mining and energy service, 30-40% of the population of Bangka island is engaged in tin mining – children, women, men. The tropical forests have been marked by thousands of small mines resembling craters, which are contaminated with acidic water and heavy metals. Tin mining takes place not only on land but also at sea. Seabed mining destroys the seabed and drives away fish. Thus, many fishermen also become miners. Digging in the makeshift land mines is done by hand, with shovels and picks. Landslides are frequent and result in miners being buried under the mud. Injuries and fatal accidents occur regularly. Of course, there is no compensation for workers or their families.

south korea

“In the cleanroom, the atmospheric pressure was very high, therefore I was very tired. I remember my life at the factory like this: work and return to the dormitory for sleep. Only work and sleep, nothing else, even in the first years after my twenties. I was very exhausted.

Park Min-Suk, worker on a silicon disc production line at a Samsung Semiconductor factory

For the first five years, we had only one free day per month. To take a free day, another worker would have to take on double the workload.”

In South Korea, there is a large number of factories that manufacture electronics, such as Samsung, LG, and also Hyundai Electronics, which, apart from cars, produces SSD drives and semiconductor memories. In South Korea, as well as in Taiwan and China, silicon wafers are produced, which form the basis for manufacturing integrated circuits (microchips), screens, batteries, and all kinds of electronic components.

The Samsung Group, based in South Korea, is a family business owned by the Lee family. Although it is a family business, it is not particularly small, as it constitutes the largest corporate group in South Korea.8 Lee Byung-Chull, the son of a wealthy landowner, founded the food trading company named Samsung in 1938, which later expanded into the textile industry and entered the electronics industry after the 1960s. His son, Lee Kun-Hee, succeeded his father in 1987, and after 1990, four separate corporate entities managed by the third-generation Lee were developed.

For South Koreans, Samsung is something more than a company that designs mobile phones and televisions. In Seoul it operates hospitals, hotels, insurance companies, etc. Large construction companies also belong to the same group. For example, Samsung Heavy Industries is one of the world’s largest shipbuilding companies. Also, the Samsung group includes Hanwha Techwin, which deals with aerospace, the construction of surveillance systems and technologies for military use.

In contrast to the plethora of information in Western media about consumer issues, there is minimal coverage of topics related to labor – let alone when it comes to labor struggles taking place in the East! Certainly, this is not their favorite subject. Although news is scarce in our parts, workers at factories in South Korea are organizing awareness campaigns about the issues they face in their workplaces, militant demonstrations, and protests. We translate an excerpt from an article on the Danwatch website9 about workers’ struggles against Samsung. The article was published in December 2014 and is one of the few we found that addresses this issue:

“Seoul. The cries of more than 700 workers and union members clashed with the steel walls of the building that houses Samsung Electronics. Tear gas rained from the sky, as correspondingly many police officers tried to keep the angry crowd under control. Their demands were clear. They demanded that Samsung Electronics stop intimidating workers who are trying to unionize. The workers were demanding rights.

The demonstration took place in May 2014, and a few days earlier, on May 16, 34-year-old Yeom HoSeok set fire to a small pile of charcoal on the floor of his car, waiting for the toxic fumes to take his life.”

In an article10 which cites the Korean Metal Workers Union (Korean Metal Workers Union – KMWU) as its source, we read that Yeom Ho-Seok, who worked as an electronics repairer, was among the founding members of the local workers’ organization of Samsung Electronics Service KMWU. The text states the following:

Yeom recently participated in a strike that began on May 9 and took part in rallies in front of Samsung Electronics Global’s headquarters in Seoul from May 12 to 14. He disappeared on May 15. He was found on the 17th of the month with two suicide notes. In the first, he wrote “like the sun that will rise again tomorrow, the local (s.t.m: organization) will win this battle without failure. (…) Continue the fight until the day of victory.”

On Sunday, May 18, the police raided during the funeral of Yeom Ho-Seok with very strong suppression forces. Throwing tear gas, they violently dispersed the crowd and arrested 25 members of the KMWU union. What was the police’s involvement during the two days of Yeom Ho-Seok’s disappearance? This remains unknown…

“According to Korean media, [Danwatch writes] the protests continued for 41 days until June 28, when workers at Samsung Electronics Service appeared to reach a preliminary agreement with management on wages, working conditions, and the workers’ ability to unionize.”

Also in Seoul, labor protests are taking place on the issue of protecting workers and workers during the production of electronics, after a large number of worker deaths at Samsung in recent years. The newspaper the guardian reported in January 2016: “Lawyers for the victims state that 244 workers in Samsung facilities that produce microchips and screens have developed rare diseases linked to hazardous conditions, 87 have died.”

The words of Min-Suk Park, at the beginning of this section, are from an interview she gave to the German blog “Faire Computer” in June 2014. Park had been working for Samsung for over 7 years. Of the 18 colleagues in Park’s department, 7 were diagnosed with serious illnesses. The sterile chambers (cleanrooms) where electronic components are manufactured and the full-body white suits worn by the female workers are measures taken for the safety and protection of the electronics. However, no corresponding protective measures are taken for the workers themselves, despite their work being extremely dangerous. The strong chemicals used in the production of silicon wafers create serious health problems for them, while many of these women, after a few years of work, develop rare diseases, leukemia, and various forms of cancer.

The workers at Samsung – in the electronics manufacturing sector, women are mainly employed – and many of their supporters have campaigned by organizing demonstrations, protests, and awareness campaigns. They demand that these incidents be recognized as occupational diseases due to working conditions, that all victims be compensated, and that a permanent, externally monitored program be established to protect workers.11

motion

“Made in China” is world-famous, and behind it there are countless workers of rural social origin like me, who toil silently in factories. We have gone through harsh job hunting, strict management, poor living conditions, regular fines, frequent punishments, dismissals, arrests when police check temporary residence permits […].

Zhan Youbing, introductory text of a photo collection titled: Working life of peasant-workers.12

The youth of workers from poor rural families fades away on the assembly line and is exported along with the products. What remains for us is injured bodies from excessive labor, spasmodic thoughts, and heavy heads after many hours of extremely meticulous work.”

The economic magnificence of information technology (IT) is built to a large extent on the backs of millions of Chinese industrial workers, who are mainly young, rural-origins internal migrants.

Much has been written about electronics assembly factories in China. The story of Foxconn is particularly well known, the company that employs Chinese workers on electronic assembly lines for Apple, Samsung and other companies. For a while it had become a topic in Western media, after the suicides of 17 young workers within the company’s facilities from 2007 to 2010.13

In 2014, the case of the appalling conditions under which workers labor in the subcontractors – suppliers of Apple and other companies gained publicity again after a BBC investigation into the Pegatron factory that took over part of the iPhone 6 production. In a BBC Panorama article, in December 2014, entitled “Apple failing to protect Chinese factory workers'” the following was written:

Exhausted workers sleep during their 12-hour shift at Pegatron factories on the outskirts of Shanghai.

An undercover reporter, who worked in a factory manufacturing components for Apple computers, had to work 18 consecutive days despite repeated requests for a day off.

Overtime is usually unpaid. Half of the workers at Pegatron have short-term contracts and are treated as expendable. The production lines are supervised by foremen who hurl threats and demean workers and workers’ representatives at every opportunity. To meet deadlines, workers must place small components every few seconds. After their grueling shifts, they are transported to dormitories—chambers where up to 14 people are accommodated. By outsourcing the production of its products, the glamorous Apple, apart from its highly valuable asset of extremely cheap labor, can also shirk responsibility for the appalling living and working conditions endured by the actual creators of its products, on assembly lines or in mines.

On this issue, a classic response from the pundits is once again: if it bothers you so much, don’t buy it! This expresses the supposed cosmopolitan guilt, accompanied by deeper thoughts of the kind “but what can we do? Should we reject technological development?”. Opinions are also often expressed that justify the situation with the argument that it is the culture of those particular countries that is to blame: “those endless working hours are something normal there” or “if we hadn’t given them the opportunity to build technology, they would still be farmers”. Such expressions and other pearls appear in the comments of articles that refer to the subject, echoing the dark thoughts of dirty minds that suffer from racism and petty bourgeois attitudes.

It is upon such arguments that more official responses from defenders of corporate interests are also based. For example, in a TED talk Leslie T. Chang14, who proclaims herself a representative of the voices of women workers, presents women as uneducated village girls who, due to factories producing products from western firms, finally gain the opportunity to go to the city and do something for themselves. “We made these poor women human” she could say in one phrase. Apple also, in a letter it sent after the BBC’s publication to its staff in Britain, writes in its own defense:

“…to know that more than 1,400 of your colleagues at Apple have been placed in China to oversee our industrial processes. They are in the factories constantly – talented engineers and managers who are also compassionate people, trained to speak up when they see safety hazards or mistreatment.”

That is: the workers there are quite helpless and accustomed by nature to mistreatment, so they don’t understand these things anyway… That’s why they need compassionate engineers and managers who will pay attention to these things and say something.

Also, later in the same letter:

“A few years ago, the overwhelming majority of workers in our supply chain were working over 60 hours, and 70+ hour work weeks were typical. […] This year, our suppliers have achieved an average of 93% compliance with the 60-hour limit. We can do better. And we will.”

60 hours! Not even 40? I mean, as if to say: we’ll try to convince them, because these Chinese don’t know how to work less… we need to gradually reduce their hours. Not disrupt their ecosystem.

Finally, we translate an excerpt from an article published on January 11, 2013 by the organization SACOM15, titled “Strike erupts against horrific working conditions at Foxconn”.

“On January 10th, a strike broke out at Foxconn in Fengcheng, Jiangxi province, demanding wage increases and dignity. The next day, more than 1,000 workers took to the streets and blocked the main road. Security forces quickly intervened to suppress the workers. According to information obtained by SACOM from first-hand sources and Chinese media, police presence is strong, with tear gas and physical violence being used to suppress the strikers. [..]

The monthly wage for Foxconn workers is $209. [..] Besides low wages, there is no respect for workers on the production line. Workers doing soldering jobs can receive a new surgical mask only every two days. [..] In winter, the temperature in Fengcheng is around 3 degrees Celsius. Hot drinking water in the dormitories is limited. Moreover, there is no access to hot water in the bathrooms. [..] The strike for decent working and living conditions is necessary and just.”

Presumably, even Foxconn’s latest announcement regarding the replacement of a large part of its workforce with robots is a response to precisely these labor demands.

The Chinese workers themselves come to overthrow with their struggles the myths of corporate propaganda, which at the same time constitute the common wisdom of the “civilized western mind”. They come to prove that all these views about “voluntary servitude”, which may in some part be due to ignorance, show something else: the racism of western societies in this case is based on hostility towards workers’ struggles.

informatics is also material

After all this, we can say with certainty that the information age has not made “the world a better place,” as it is preached. Indeed, it cannot even be dressed in the veil of humanism. Not at least convincingly! A smartphone, besides being a witness to the culture of the new technological paradigm, is also a witness to the globalization of labor. The smartphone is also a witness to the extreme barbarity of employers towards the working class, of “Western civilization” towards the rest of the world. Extreme barbarity and savage exploitation of the labor of proletarians on a global scale and in the information age!

The same applies to all products that involve more or less technology, such as clothing, cosmetics, and even vegetables. The journeys of all these products may be difficult to describe in detail. However, even through a sketch of them, it becomes evident that the interdependence between the different – nationally separated – working classes is the norm of modern capitalist production. Meanwhile, a strike here or a demand there may seem like unrelated events; not so dangerous, when they occur sporadically. The possibility of a future connection between such “events” may seem distant. However, the bosses who do not know homelands when it comes to such matters (they guard nationalism as poison for the “poor”) keep watch and take care: to divide, to undermine, to blackmail, to kill; preemptively, everywhere in the world.

In the case of technological products, the issue has an additional interest. On one hand, technological achievements are enshrined in the mind, not as products of global labor, but as creations of large corporations. On the other hand, technological development is presented as the overcoming of the old world, as an upgrade. The illusion that we live in an advanced world that has left its problems behind has been largely established as the dominant impression of Western citizens, as a reversal of cowardice and the rejection of any possibility of claim.

Views that more or less identify technological development with liberating progress are logically expressed by academics who live detached from the reality of production relations, or by those who have business interests. Such findings only succeed in concealing the impact of the technological restructuring of capital on labor and its global dimension.

We, from our working-class position, find it difficult to see the automatic emergence of this famous liberating dimension of technology. On the contrary, we see an expanded field of conflicts that lie precisely at the heart of the production of new technologies. From the mines, to…

Shelley Dee

- A Yale University study published in early 2015 deals with the issue of criticality in the supply of metals used to produce cutting-edge technology. We translate from the YaleNews page a paragraph from the article “Metals used in high-tech products face future supply risks,” March 23, 2015, by Kevin Dennehy, which refers to this particular study.

Among the factors contributing to extreme criticality challenges are the high geopolitical concentration of primary production (for example, 90 to 95% of the global supply of rare earths comes from China), lack of available substitutes (there is no sufficient substitute for indium, which is used in computer and mobile screens), and political instability (a significant portion of tantalum, widely used in electronics, comes from the war-torn Democratic Republic of the Congo).

http://news.yale.edu/2015/03/23/metals-used-high-tech-products-face-future-supply-risks ↩︎ - You can find more information about rare earths in Sarajevo at the articles: “rare earth materials (it’s not a band!)” and “rare earths – familiar competitions”. ↩︎

- International Rescue Committee, Measuring Mortality in the Democratic Republic of Congo

http://www.rescue.org/sites/default/files/resource-file/IRC_DRCMortalityFacts.pdf ↩︎ - The excerpt is translated from the book: Africa in the New World Order: Peace and Security Challenges in the Twenty-First Century, Lexington Books. ↩︎

- According to the Wikipedia article for the mineral coltan:

Coltan imports from the DRC to Europe are mainly directed to Central/Eastern Europe and Russia. These shipments primarily travel by road from Dar es Salaam (Tanzania), Piraeus (Greece) and then to the Balkans. Nova Dies, an offshore joint venture based in the British Virgin Islands, mainly controls the network through the Balkans. This network mainly transports unprocessed coltan from uncontrolled informal mines and thus hinders the development of the processing industry in the DRC. ↩︎ - EXPOSED: CHILD LABOUR BEHIND SMART PHONE AND ELECTRIC CAR BATTERIES, 19 January 2016, Amnesty International ↩︎

- In 2014, a U.S. court (U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit) ruled in favor of a petition filed by three business groups against this specific regulation, deeming it unconstitutional. The court specifically decided that the regulation violates freedom of speech, as it forces companies to condemn their own products (!). ↩︎

- In South Korea, the equivalent of a corporate group is the term chaebol (chae: property/wealth + bol: clan/family). The difference from classical corporate groups is that the management of the entire group belongs to one family and is passed down from generation to generation. “At least 15 relatives manage more than 55 companies, with total sales of 33.5 billion dollars,” reports Forbes magazine in 2015 regarding Samsung’s chaebol. ↩︎

- According to the self-presentation on Danwatch’s website – it is an independent news medium and research center that publishes investigative journalism articles. It was founded in Denmark in 2007 by a coalition of consumer organizations, non-governmental and philanthropic organizations. ↩︎

- From the website of the GoodElectronics network, which consists of organizations and bodies dealing with workers’ issues in the electronics industry from the U.S.A., Europe, India, Malaysia, the Philippines, Mexico, and South Korea. ↩︎

- For more information, you can visit the website of the Stop Samsung – No More Deaths! campaign by the group SHARPS (Supporters for the Health And Rights of People in the Semiconductor industry) which is active in Korea: https://stopsamsung.wordpress.com/ ↩︎

- Zhan Youbing is a photographer who was once a factory worker. Since 2006, he has taken over 40,000 photographs focusing on internal migrant workers in China. Link: http://www.photoint.net/picture-615.html ↩︎

- More on the subject can be found in the article by Sarajevo “on the other end of the iphone”, issue 78 ↩︎

- She is a journalist and was the Wall Street Journal correspondent for China. You can watch her talk here:

https://www.ted.com/talks/leslie_t_chang_the_voices_of_china_s_workers?language=en ↩︎ - SACOM (Students and Scholars Against Corporate Misbehavior) was founded in Hong Kong in 2005, following a student movement to improve working conditions of workers in outsourcing companies. ↩︎