At the end of the ’60s, a pregnant young woman, a mother for the first time, carefully opens a leather-bound notebook with white pages. She notes the date and year at the top of the first page, in clear letters. And below she continues:

Today, my beloved little boy, I begin this diary of yours, which I will try to keep for as long as I can, and I say for as long as I can because I barely manage the chores that your presence causes me.

… When you were born, your little head right there at the top was swollen and soft. It was from the position you had in the womb. Your features were stretched. As soon as they prepared you and dressed you, the head of the clinic brought you to your little bed. Shortly after, when they brought you to me and I saw you, I said to your father, “how ugly our child is,” but this did not diminish my love. Your father was overjoyed, that evening he stayed at the clinic with us…

A personal moment of a personal relationship, undoubtedly… Together, however (and this is what we want to point out), a certain social field within which this personal relationship, commonplace in many respects, is imprinted. On paper. In a diary.

The handwritten diary is a specific relationship with time. There is the today here; with its heading, the date. There is earlier, as one leafs through the pages backwards, the solid trace of yesterday and the day before yesterday, of the previous week, of the past month, of the past year. There is the past, realized as narrative or as note or as comment.

And there is, also, the future. Not as the unwritten pages of the notebook. But as the unknown time during which the author will return, by choice, to yesterday; while this each time current tomorrow will have left additional traces, marks, words, phrases on the paper.

Personal confessions on paper, of a new mother who breastfeeds, changes diapers and lulls her baby to sleep, are written, imprinted, accumulated in an organized manner, giving a specific form to the days (and nights) – as – relationship. It could have been another relationship; romantic, friendly… Another diary content. However, it would still have been something similar. Not the memories of the mind that sometimes blur, reform or are lost. Nor the thoughts about tomorrow, about the after, which at times are torrential and at others slow and repetitive like an endless loop. Entries: a specific organization of time (through writing), its haste or tranquility. Diary: not, simply, a notebook for memory; but a way of retaining the duration of (daily) experience.1 This retention of this duration not for “future use” but now. From some perspectives: the diary was a delay of daily time, especially where it was (or seemed) dense. A handmade, bodily brake; a stance – not merely of the now, but of the now in its relationship to yesterday and tomorrow.

The body (the female body, the body of a baby)· time· relationships· experiences: these change, their change has begun from many sides. The fact that the changes (radical from many perspectives) are made voluntarily, this is certain. Whether they are conscious as such, this is doubtful. The changes happen imperceptibly. Either because there is no measure of comparison, or because those involved do not want to make such comparisons.

Our question is not about moralizing (about such or other changes in social relations, ideas, beliefs about “normality”, representations); whether they are “good” or “bad”. Our question (political from the outset) is whether they are recognized as such. When you are not conscious of what you are ultimately doing, you can moralize foolishly. If you are conscious, you may realize that you are making choices. And, most importantly, that choices have consequences.

perfecting fertility: the digitized reproductive citizen2

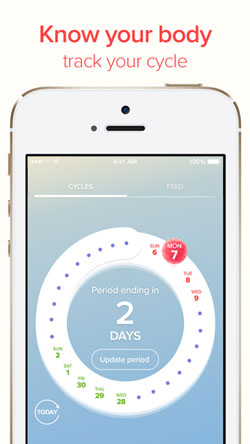

Women have been involved in practices related to their fertility and reproductive functions for years. Where once they might have noted their sexual activity, menstrual cycles, signs of ovulation, and developments in their pregnancy with paper and pencil, there is now a plethora of digital technologies that support women in monitoring, measuring, and visualizing these aspects of their bodies. The development of the internet has allowed the use of online computers for tracking periods, ovulation, and pregnancy, searching for information regarding conception and pregnancy, and participating in discussions with other women in online forums. […] Over the past decade, easy access to the latest digital technologies provides many opportunities for women to create online content, monitor their bodies with increased measurable accuracy, and share their personal data on social networks. These varied possibilities for producing and sharing personal information around female sexuality, fertility, and reproductive capabilities have extensive consequences. At the very least, these aspects of female bodily experience have moved from the realm of the private to the field of the public.

In this text I focus on digital technologies that have been developed specifically for female fertility and pregnancy. These technologies span computational platforms, apps available for mobile phones and tablets, and wearable self-tracking devices. I argue that devices and programs of this type contribute to shaping the subject of the digitized reproductive citizen, or in other words, the woman who uses digital technologies as a way to devote great attention to her health, fertility, sexual behavior, and well-being. These technologies intensify an already frenzied atmosphere of self-monitoring and self-responsibility within which female reproduction is experienced and enacted.

In addition to these already entrenched regulatory recommendations, there are new expectations regarding how women should use digital technologies as part of their reproductive capacity and the management of the data sets produced by these technologies. The most personal and specific details about themselves—generated as women use digital technologies—have now been invested with commercial value. The digital content deliberately created by users and the digital data byproducts left behind by every simple transaction and activity, such as online searching, enter into the digital economy, where information about bodies and behaviors holds commercial, administrative, and research value. Personal data of women related to their fertility and pregnancies, generated through such practices, circulate and are reused for a wide range of reasons, by a wide range of actors and services. Women may know about and have consented to some of these practices, but certainly remain unaware of others.

[…]

In this text, theoretical approaches have been incorporated that attempt to understand the ways in which female embodiment is perceived and experienced. As various cultural theorists (Grosz, Shildrick, Ussher, and Longhurst) have pointed out, female bodies in western societies are typically rendered intelligible and represented as inferior, due to their apparent fluidity, their leaks, and their inability to retain. This is particularly the case for women who ovulate, menstruate, are pregnant, give birth, or are in menopause. Their bodies are considered more open to the world and less controlled than male ones, under the influence of female hormones that cause irrational or excessive emotional behaviors or due to the production of bodily fluids that threaten to leak from their bodies. I bring together these theorizations of female embodiment with theories of social-materialism to examine the role digital technologies play in the representation, normalization, and shaping of female reproduction.

the digitization of pregnancy and the unborn

Human bodies are increasingly being digitized as a wide range of digital technologies has been developed aiming at representing and monitoring bodies. These include digital medical imaging technologies, photos uploaded to social networks, and digital data produced by voluntary biometric monitoring using apps or wearable devices. Through such processes and technologies, human bodies are shaped as collections of digital data—aggregations of digital data—that constantly change as new data is generated and accumulated.

With the advent of mobile and ubiquitous computers, devices for representing and monitoring female fertility, pregnancy, and the unborn have now moved outside the clinic and into the public arena. Beyond blogs, websites, and discussion forums, there are now videos on YouTube, photographs distributed on platforms such as Instagram, specialized pages on Facebook, hashtags on Twitter, groups on Google and Yahoo, and Wikipedia, providing information and support on female reproductive health. Women can use apps, digital platforms, and wearable devices to record their period and ovulation, sexual activity, attempts at conception, and pregnancy. These new media create and shape novel ways of representing the female reproductive body, which, as a consequence, has become more visible than ever. The same applies to the unborn body, which is more visible, so that the public embryo—at all stages of development, from the moment of fertilization to the moment of birth—is now available to the public gaze on websites and social networks.

The development of new programs related to female reproductive health has contributed to an even greater transparency and visibility of menstruation, ovulation, pregnancy, and unborn bodies, as well as to the establishment of new ways of monitoring these bodies. There are many apps available for women to track their sexual activity, ovulation, menstrual cycles, related symptoms and signs, attempts at conception, and pre-conception practices. Some apps remind women to take their contraceptives; others send notifications that their period is approaching or that it’s time to change their tampon. A range of bio-sensor technologies is also available for fertility tracking. Women can purchase wearable devices with sensors that measure basal body temperature (the lowest temperature recorded during rest and serves as an indicator of ovulation or its absence) and synchronize with other fertility tracking apps. There are other devices that measure electrolytes in saliva (placed on the tongue) or cervical mucus that changes according to estrogen production (this device is inserted into the vagina) and send information to a program that displays the results in charts and diagrams.

As soon as a woman achieves conception, hundreds of pregnancy-related apps become available. An analysis I conducted in June 2015 of all pregnancy-related apps on both the App Store and Google Play showed that the vast majority of them can be categorized into three groups: “entertainment,” “pregnancy and embryo tracking,” and “pregnancy information.” Entertainment-focused apps included games such as inviting friends and relatives to guess the baby’s name, gender, birth date, weight, and height; creating personalized birth announcements for friends and relatives; fake ultrasounds and various pregnancy quizzes. Various games for young girls invited them to take care of a pregnant character or even assist in childbirth. Other apps allow women to photograph their pregnant bellies week by week and create videos with sequences of images as the belly grows. Other apps encourage women to keep a diary of their experiences and feelings during pregnancy. Another type of app is designed to help women choose products for themselves and their babies.

Many pregnancy and embryo monitoring apps direct and encourage women to observe and record detailed data not only about their body: their diet, vitamin intake, fluid consumption, physical activity, pregnancy symptoms, mood, results of medical tests, body weight and body temperature. Various such apps include countdown clocks until birth, so women have an accurate picture of the time remaining. There are other apps that use the pregnant woman’s body as an entry point or intermediary to record the good condition of the embryo. Some others encourage women to record and closely monitor even the slightest movements of the embryo. Some work together with various mobile accessories (mini Doppler devices) so that women have the opportunity to record the embryo’s heartbeat whenever they want. Another group of apps facilitates the progression of labor, recording contractions in detail for example. And many of these apps have features that allow women to share all these details on social networks.

Some technologies related to female fertility, sexuality, and pregnancy are embedded within a spectrum of interconnected programs and devices, as part of what they offer. Platform programs often work with their own custom apps or other apps, as well as with wearable self-monitoring devices. Within this interactivity, users can upload a variety of personal bodily details, either entered manually or, in some devices, automatically collected and processed by sensors. Fertility, sexuality, and reproduction are often interwoven with other aspects of embodiment in these technologies, thus extending into the realm of physical fitness and emotional well-being.

A key point for the sales of many such technologies (as well as other information and self-monitoring devices related to health, sexuality and physical condition) is that their use provides better knowledge of the functions and behavior of the reproductive body. Thus, for example, the Glow platform and the associated app provide daily forecasts for the probability of conception and determine the next fertility phase, through the processing of data entered by users. The Glow website advertises its services with the slogan: “Female nature: demystified with data”. An app offered by Glow is Eve, which records menstruation and sexual activity and allows users “to know what’s going on down there”, while claiming that the namesake app will allow users “to perfect their fertility”. Using Glow includes entering more than forty different “health indicators” needed to form a “daily cognitive health calendar”. Personal information required includes period cycles, ovulation indicators, findings, basal body temperature, cervical mucus, body mass index, cramps, contraceptive use, physical exercise, skin marks, period flow and period symptoms. Glow also offers a similar app for the user’s partner in order to measure his own fertility. The program coordinates with data entered from Google Fit and My Fitness Pal physical activity trackers and also helps women renew their contraceptive prescriptions at selected pharmacies. Users receive regular reminders to take their medication and use contraception, if they want to avoid conception.

When pregnancy is achieved (the developers of Glow claim that 25,000 pregnancies were achieved in the first year thanks to using the program), another app from the same company – Nurture – is provided to the woman with the aim of taking care of you while you take care of your baby, entering additional details about how the body changes. Users are encouraged to participate in uploading their personal data, to receive “more personal health diagnoses” that “will guide you to a healthy pregnancy.” This collection of information and the practice of uploading it, combined with the algorithmic handling and visual representation offered by Glow, are presented as what allows women to take control of their otherwise mysterious and unruly body. In addition, a “Glow community” is presented as an opportunity for women to communicate with other users of such technologies.

Another example is the digital platform Ovuline and its related apps. According to Ovuline’s website, by using what it offers, women “will conceive faster, have a healthier pregnancy, and learn their body.” Users are encouraged to measure and track a wide range of bodily indicators and activities, using various digital devices (exercise and sleep monitoring devices as well as electronic trackers, all available for purchase from the site), and also to input various data into the database. Women are prompted to upload the data they collect through the devices or manually enter data regarding their diet, exercise habits, blood pressure, weight, mood, health status, and sleep patterns. All these data are collected and combined in order to generate calculations (expressed through charts and interactive timelines) that are used to provide advice on whether the pregnancy is following normal standards and to create “personalized diet and weight plans.”

Digital platforms and apps have also been designed towards the direction of reducing healthcare costs for pregnant women. The Due Date Plus app, for example, was developed by the health company Wildflower and provides a range of flexible health plans for people who have health programs in the US. As noted on Wildflower’s site: “our mobile programs connect to the health system and focus on practices and decisions that can reduce healthcare costs for our customers”. The Due Date Plus app provides a range of services for users, from targeted health information, to information about what the health program covers and tools for monitoring weight or symptoms. Many pregnancy-related apps use gamification techniques, as a method of promoting sales. Gamification has also infiltrated pregnancy care. Healthcare providers in the US have started to push pregnant women to use gamified programs, in order to find out if they are following the proper health regimen. Once they subscribe to the program, pregnant women unlock online game blocks as long as they attend their appointments regularly and if so, they receive gift vouchers as a reward.

the digitized reproductive citizen

There are many key meanings and practices reproduced and shaped by digital technologies around female fertility and reproduction that I described above. One of the central characteristics of these technologies is their implicit assumptions regarding women’s needs, desires, and interests. They presuppose a subject who is ready and willing to produce information about her fertility and reproductive capacity and to enjoy the supposed privileges offered by the technical ease of digital technologies, such as, for example, entering personal information, watching this data become the object of algorithmic handling, and having it presented back to her in measurable or graphic form. Moreover, these technologies assume that the user conforms to the idealized position of the reproductive citizen.

The reproductive citizen follows the broader idealistic concept of the health-promoting citizen. This citizen, a key figure in the neoliberal political environment, takes responsibility for their own health, well-being, and productivity without requiring support from the state. These practices often appear through the use of digital technologies in self-care and health promotion. When neoliberal perceptions focus on women’s reproductive functions and capabilities, then not only are the women themselves involved, but also their offspring (actual or potential). Over the past centuries, the attributes ascribed to infants have been extended to unborn entities, as they acquired increasing value as a kind of proto-humans, individual personalities with their own worth and rights, vulnerable beings requiring maximum care and protection. Aligned with reproductive citizenship is the concept of embryonic citizenship, which has recently emerged. These representations of the unborn have contributed to the close perception that portrays the pregnant body as a vessel for transporting and caring for this precious entity.

The pregnant body is typically represented as both dangerous and at risk simultaneously. The pregnant woman is considered dangerous because she is potentially capable of threatening the health and development of the unborn if she does not adequately regulate her body. More symbolically, pregnant women are often portrayed as abject bodies—repulsive, fat, ungainly, out of control, leaky, permeable, ambiguous—and therefore dangerous to social and moral order. Pregnant women are seen from their position as “at risk” because a plethora of risks and threats are supposedly surrounding their bodies, against which they must defend themselves, once again primarily for the sake of their embryo. When they appear to disregard these expectations and put their unborn “at risk,” they are subjected to intense moral condemnation and, in some cases, even criminal prosecution.

In pregnancy programs and devices, the boundaries between the needs of pregnant women and their unborn are extremely blurred. Many of these technologies are exclusively oriented toward providing capabilities for caring for and optimizing the development and health of the embryo through the pregnant woman’s body. Thus, for example, while many apps are designed for pregnant women to record their diet, exercise, mood, and more, the ultimate beneficiary of her self-monitoring efforts is her embryo, for which she is burdened with care and responsibility. Some apps, such as Glow Nurture, encourage pregnant women to include their partners in this self-monitoring effort by sending them messages, for instance, if the pregnant woman failed to exercise enough or drink sufficient water on a given day.

Many such apps have been downloaded by thousands to millions of users. Among the top health and fitness apps on Google Play on 21/10/15 for example, Period Tracker was ranked 7th, with 10 to 50 million downloads. MyCalendar – Period Tracker was ranked 21st, with 5-10 million downloads. The top pregnancy apps were ranked 23rd (What to Expect Pregnancy Tracker, 1-5 million downloads) and 27th (Glow Nurture Pregnancy Tracker, 50-100 thousand downloads). A market research study showed that pregnancy apps are used more than those focusing on physical fitness.

[…]

These technologies present the ideals of reproductive citizenship through flexible, accessible, and often highly appealing and aestheticized forms. Platforms and apps such as those offered by Ovuline and Glow feature beautiful images of embryos or pregnant women and happy, charming young couples with smiling babies. Games for young girls have players taking care of pregnant female figures so they can shine through brushing, dressing up, and changing their appearance, supposedly to develop the confidence to be pregnant with style. Some apps that track menstrual cycles or ovulation use archetypal feminine imagery of colorful flowers or circular shapes (to symbolize fertility and reproductive cycles) or images of babies or charming young women (one company uses the image of a stylish smiling uterus to promote an ovulation tracking app). Gamification elements in many of these apps portray self-monitoring during pregnancy as a fulfilling and engaging experience and sharing personal information as something worth enjoying with family and friends.

The focus on the aestheticization of menstruation and pregnancy reproduces ideas about the importance of maintaining physical attractiveness during these bodily states, not allowing the body to become unappealing or inappropriate. Moreover, by offering measurability and algorithmic analysis, these technologies rationalize monitoring and calculation, providing information and opportunities for playfulness and celebration of female fertility and pregnancy. They promise to tame, aestheticize, and limit the risks and anxieties arising from the instability and unpredictability (and sometimes discomfort and pain) of bodies experiencing menstruation, ovulation, pregnancy, or childbirth. As the developer of Clue (a popular period-tracking app) put it in an interview with the New York Times:

“There’s a basic need among women to understand their bodies and learn more about them… When bodily knowledge goes up, it creates a sense of being in command and in control.”

commercializing the digitized reproductive body

The activation of women’s involvement as digitized reproductive citizens has indirect economic and political consequences. However, these consequences extend far beyond efforts to reduce state expenditures in the health sector or to ensure a satisfactory number of new and potentially productive citizens (i.e., healthy infants). The data generated carry new forms of commercial value, not only for the pregnant women themselves and their close ones, but also for other third and fourth parties. In the global digital knowledge economy, people’s personal information has been commodified, harvested from digital files, and sold as products for commercial, advertising, research, and administrative use. Just as women’s wombs and eggs have been transformed into elements of the bio-economy as part of the trade in reproductive medicine and surrogacy, so too have the data produced by women regarding fertility and their reproductive functions and capabilities acquired commercial value. Like other digital data related to the human body, reproductive data can be considered to possess a kind of bio-value.

The woman trying to conceive or already pregnant is part of a particularly valuable demographic group. This woman is considered to need an array of new products and services for herself and her infant. For this reason, it has been calculated that market players pay significantly more for the data of pregnant women’s online browsing compared to other users. If a woman announces her pregnancy on her social media page, downloads a pregnancy-related app, makes online purchases related to pregnancy, or searches the internet for pregnancy-related information, her status is quickly recognized by internet companies, commercial firms, and third-party data buyers.

Gamification has been described by many commentators as a way for developers to gain access to users’ personal data, luring them into participating in various processes, using deceptive practices. This is certainly evident in pregnancy-related programs. Encouraging pregnant women to download apps (which alone allows developers to access some personal information) and then customize them with even more personal information about themselves and their embryo; monitoring changes during pregnancy; observing how the embryo grows and develops, how it moves and how its heart beats; sharing these details with others, all these are processed and converted into a marketable product for second and third parties.

Some apps, such as BabyCenter’s My Pregnancy Today, target users with advertisements as soon as they open the app. BabyCenter belongs to Johnson & Johnson, which supplies many products for pregnant women and babies, from clothing to strollers and diapers. The range of apps it offers includes My Baby Today and Birth Class, as well as an ovulation detector, thus collecting personal data on female fertility across the spectrum, from menstruation to the early stages of motherhood. According to a news article, a BabyCenter vice president had commented that the company uses its apps to capitalize on the knowledge they gather regarding the pregnancies of subscribing women, including their due dates. This date is very significant for advertisers, because they can then target the woman with advertisements and offers tailored specifically to her. BabyCenter was one of the companies mentioned in September 2013 during an investigation conducted by the U.S. Senate Commerce Committee regarding data brokers and the collection of personal data used for advertising purposes. Companies from other industries have equally recognized the value of personal data related to pregnancy and motherhood collected from online forums and apps, such as car manufacturers, real estate agents, financial and insurance services.

Personal medical and health information is a prime target for a wide range of actors and services: not only legitimate businesses such as internet corporations, companies that engage in data mining, and advertising and insurance companies that subsequently purchase the data, but also cybercriminals, who profit by selling such information on the black market, or attempt to defraud insurance companies with fake claims, or gain access to medications and medical equipment. Women who use digital technologies for reproduction, therefore, may themselves be vulnerable to privacy and security violations, risking their personal bodily information being used illegally or disclosed in unpredictable ways. Nevertheless, in the research I conducted with women using pregnancy apps, I found that they were not particularly concerned about how their personal data would be used by others.

conclusion

Digital reproductive technologies allow women to measure elements of their bodies in great detail and compare their data with other users of these technologies. Their personal reproductive data are collected together with others in large data collections, creating new norms regarding female reproduction, which in turn are used to further develop the algorithms that interpret women’s information and make predictions. Such technologies therefore open avenues for how personal information, even on very intimate bodily matters, can be distributed and compared.

Potentially, there is great pleasure in using reproductive technologies and devices. Women during menstruation, trying to conceive, pregnant or in menopause, often experience their bodies as uncontrollable and unpredictable, and these experiences can be combined with feelings of helplessness, shame, inadequacy and loss of control. In this socio-cultural and political environment, it is not surprising that health technologies around fertility and reproduction that claim to help women better understand their bodies are popular. Pleasure can come from collecting information about the body and achieving a sense of control over reproductive cycles; the efforts to conceive; concentrating information about pregnancy and sharing it with relatives and friends; fantasizing about how an unborn develops and changes. As I have already observed, many of these technologies have playful and aestheticized elements that make monitoring and recording reproductive phases and pregnancy a fun and celebratory experience.

These programs tend not to recognize the possibilities of women who may be ambivalent about becoming pregnant, who choose not to engage in detailed self-monitoring, who are without a partner or in a same-sex relationship, or who do not conform to the stereotypes of hetero-normativity or the ideals of reproductive citizenship. In all digital reproductive technologies offered to women, female sexuality is represented as oriented exclusively towards issues such as avoiding or achieving conception, preparing for pregnancy and avoiding risks. Given the weight of expectations and the moral content surrounding the potentially uncontrollable female body that requires strict surveillance and regulation, it is very difficult for women to compete with or resist the norms and demands embedded in these digital technologies. For women trying to conceive and pregnant women especially, doing so carries the risk of being characterized as failing to conform to the idealistic standard of the reproductive citizen. The weight of social outcry against such “bad mothers” is unbearable.

The commodification of women’s personal information also requires recognition. These technologies deploy users and their reproductive organs in the expanded digital knowledge economy, in which users are shaped as data aggregates, often for profit. Women who use such digital reproductive technologies, while conforming to the expectations of reproductive citizenship, also contribute, and in fact donate, their valuable personal information to commercial companies in ways they may not fully understand. Therefore, the private and personal reasons why women decide to engage as digitized reproductive citizens, and the work they invest in this direction, are sides open to exploitation by various actors and services. The emerging digital practices of “perfecting fertility,” therefore, bring together the private and public spheres in new ways.

Harry Tuttle

- It is certain that the diaries appeared among literate populations; in people who had gone to school and had become familiar with writing and reading. This does not mean that the “illiterate” lacked ways of daily – engravings – of time… from their body itself as things of the house and their natural environment. ↩︎

- Title of the original: “Mastering Your Fertility”: The Digitised Reproductive Citizen. Written in October 2015, and is a chapter of the forthcoming (in England to be published within October) book Negotiating Digital Citizenship: Control, Contest and Culture. The concept of “mastering” refers to ownership, which combines control with improvement.

The author Deborah Lupton is a professor at the University of Canberra (Australia), at the Research Centre for Media and News, of the school “arts and design”. ↩︎