“Every time someone uses Google’s services, they participate in at least a dozen experiments.” This statement was made in 2012 by Google’s chief economist during a conference organized by the company itself. And he continued, revealing that every year, as part of this ongoing recording and analysis of user activity, the company focuses on more than 500 study subjects and conducts over 5,000 experiments. If these figures refer only to Google, imagine how many experiments might be conducted overall by all kinds of corporate and state entities that dominate cyberspace. The conclusion from such a calculation would be that we are not simply dealing with a barrage of such “researches,” but that the internet is essentially one continuous experiment—with us ourselves as the test subjects…

Every day, millions of tests, studies, and experiments manage and direct the content we see online, in order to x-ray us, record us, and also guide us, mostly aiming for profit—but not only that. The “treasure” of accumulated personal data and advanced manipulation techniques has reached such a scale that simple profitability is now almost banal—a trivial goal that falls short of the ability to control—not just monitor—at a massive scale. That’s big business!

Understanding the internet as the largest experiment in control and manipulation in human history does not necessarily imply “dark forces” that conspire and plot in digital corridors, although such forces are not absent. For the most part, these experiments are conducted under the guise of corporate competition, and the tragic aspect of the case is that many dimensions of this phenomenon—which transforms daily life into material for observation and intervention—are favorably accepted by the public, provided they are accompanied by the assurance that everything is done to improve “the services provided” and the “online experience.”

Consider for example your daily experience from the internet. You will have noticed that the websites you visit – whether it’s the results on some search engine, articles on some news site, or pages on social media – are not exactly the same as those seen by another user or by you on another machine. This is partly due to different declared preferences, partly to history and cookies (those permanent spies on every machine) but mainly it is due to the extensive application of A/B testing technique. “A/B tests” are what their name implies: different versions of the same content, which are “served” to different users, in order to measure reactions, evaluate customer habits and accordingly adapt the content. The reason why A/B testing plays a decisive role in the policy of internet companies is because on one hand they are easy and cheap to implement and on the other hand they lead to results that could not even conceivably have been predicted without testing. For example, Google found that slightly changing the blue hue of links in search results caused a multiplication of clicks and increased its profits by 200 million dollars.

This particular example may seem “neutral,” but the intensity of online experiments is such that their results have escaped the realm of “research” and now fall into the category of crude manipulation. The Facebook example of the “emotional contagion” experiment (previous issue, don’t believe the hype) doesn’t even count among the glaring exceptions. Another case: news websites have ended up simultaneously “serving” up to 25 different versions of their content (the arrangement of material, headlines, article structure), using special software to record and analyze user engagement and user profiles according to their reactions. Another case: one of the largest dating sites, OKCupid, deliberately deceived 4% of its 30 million subscribers by sending them fake messages from other random subscribers claiming they wanted to get in touch. The reason? According to OKCupid’s co-founder: “this amounts to 300,000 online encounters that otherwise would never have happened. Of these 300,000 cases, 50,000 people might have started a conversation they otherwise wouldn’t have. And perhaps 5,000 of them eventually went on a date—all thanks to a random experiment.” Another case: within circles of websites specializing in online scams, the use of “dark patterns” is widespread—essentially tricks and design techniques whose effectiveness has been verified through A/B testing, pushing users to do something they otherwise would never have done; for example, unwittingly checking a box that grants the website access to a range of personal data.

The tools now available to the masters of cyberspace—whether they are corporations, criminal organizations, or state agencies—are such that they no longer need to maintain the facades or observe the conventional limitations set by law. Such was the case with Google, which in 2012 was revealed to have, under the guise of a certain “research” project—allegedly modified in scope by a single company engineer—accidentally collected data from millions of domestic wireless networks through its Street View vehicles between 2007 and 2010. The collected data included email accounts, passwords, personal information, and even precise location data of residents. The consequences? Simply that the company pledged to cease the data harvesting and promised not to use the gathered information. Unquestionably!

Five thousand experiments every year, by just one company, and this concerns the distant year of 2012… We don’t know whether it’s Google or some state agency like the NSA that holds the reins in this field (most likely we would be among the last to ever find out, if we find out at all), but certainly Facebook is the company for which the most has been revealed. Perhaps it has to do with the nature of the services it provides and the voluntary submission to social media norms by a massive group of experimental subjects, but the fact that user manipulation is considered more or less necessary for improving virtual sociality allows a certain degree of publicity. The following list includes some of the most characteristic cases of studies/experiments conducted by Facebook.

Case 1: Spreading rumors

Subject: the ease of spreading a lie

Time: July – August 2013

Number of users: unknown

Initially, the researchers studied more than 200,000 comments on photos which contained links to snopes.com. Snopes is a site that debunks/disproves internet rumors, so a photo accompanied by a relevant link was an example of someone who was deceived and subsequently spread the rumor within their circle of friends. Subsequently, the researchers focused on two specific photos (one allegedly showed the victim of a non-existent murder and the other accompanied the “news” that Obama would tax non-pharmaceutical products, such as clothing and weapons to support the healthcare system) in order to study the extent and intensity of their spread.

The conclusion was that users are gullible and quick to spread rumors. The more outrageous a rumor is, the more and faster it spreads compared to its debunking. However, the experiment also showed that posts flagged as false by snopes are four times more likely to be deleted.

The significance of this research compared to others may be small, but it confirmed Facebook’s ability to identify the most gullible users who spread fake rumors and to keep an analytical record of the nonsense a user has posted, even if they have deleted it. This study gained greater significance once Facebook evolved, among other things, into a news service, and therefore, as such, has a greater interest in properly handling rumors.

Case 2: Calls to friends for help

Subject: who asks for help for something on Facebook

Time: 2012, during two weeks between July-August

Number of users: 20,000

Researchers studied changes in users’ public profiles, looking for requests from them, such as “what movie should I watch?”, “is it okay to eat expired canned food?” or “what is the shortest route to the airport?”. They were more interested in the type of people who asked for help with something, rather than whether there was a response. One conclusion was that users who rarely visit Facebook, but have many online friends, are more likely to ask for something.

To the extent that the study concerned public information that users willingly share, it is no surprise that there are those who collect, process and categorize this information. One thing is certain: such data constitutes a “treasure” for companies that seek to promptly respond to the “needs” and “desires” of potential customers.

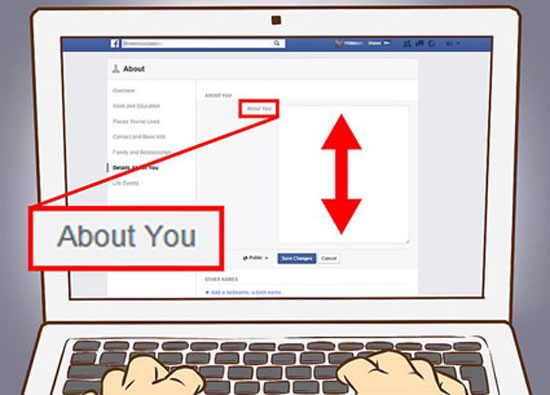

Case 3: Self-censorship on Facebook

Subject: the percentage of users who self-censor and do not publish their thoughts on the network

Time: 17 days of July 2012

Number of users: 3.9 million

Facebook recorded every entry of at least five characters in comments or in the new posts field that was not published within ten minutes. The company concluded that we think much more about a topic than what we finally decide to record on digital “paper”. 71% of users “self-censored”, withdrawing comments that were ultimately never published.

During the research, keystrokes were recorded regardless of the privacy level set by the user, although the company claimed – though it was naturally impossible to verify – that only the attempt to post was recorded and not the content. Even so, this research led to Facebook being accused for the first time of acting as “Big Brother,” monitoring its users not only in what they publicly do, but also in what they don’t do or hesitate to do.

In terms of Facebook’s direct interests, the purpose of this research is clear: to identify and reduce or eliminate the factors that trigger users’ inhibitions, in order to increase the amount of published content and consequently strengthen the connection of online customers with the company. In the broader social context, that of the digital orchestration of the everyday lives of hundreds of millions of social network users, conducting such research reveals even more: it’s not only active participation in online activities that is subject to monitoring, recording, and ultimately manipulation, but equally its absence; inertia and disengagement, once a relationship of digital mediation has been established, do not constitute a defense or protection from the watchful eye of companies, but equally exploitable material for electronic profiling.

Case 4: The impact of sharing on users’ choices and the consequences on attitude adoption

Subject: does the publication of a user’s intention to proceed with a purchase push their digital friends towards the same choice?

Time: 2012, over the course of two months

Number of users: 1.2 million

Users who claimed a “Facebook offer” (for example, a significant discount offer on clothing from a well-known brand) were divided into two groups. In one group, the users’ choice to claim the offer was automatically shared with all their “friends” through the news feed. Members of the other group were given the option to decide whether they would announce their purchase, with a button allowing them to inform their friends if they wished.

What Facebook found was that friends are more likely to end up making the same purchasing choice if there has been active notification beforehand. However, in absolute numbers, more purchases are made when the news feed is bombarded uncontrollably with notifications. The study also showed that members of the two groups ended up with extremely different online behaviors, depending on whether they had the ability to inform their friends themselves or it was done automatically. Ultimately, what the experiment documented was that limiting the user’s active participation (even if “imperceptible” or at points that may be considered “neutral”) and applying automated processes (in reality, centrally controlled processes) increases the company’s manipulative capabilities.

Case 5: Social interaction in advertising

Subject: advertisements are more effective if they are accompanied by names of friends

who approve them;

Time: 2011

Number of users: 29 million

One group of users saw ads with the label “liked by your friend so-and-so,” while the second group saw ads without this label. The conclusion – did it really need an experiment for this? – was that the stronger the bond with the person who promoted the ad, the more likely the user was to click. Exactly the kind of experiment one would expect from an advertising market giant: a thousand and one ways to disguise an ad as a “conversation between friends.” Facebook, however, had to deal with a plethora of complaints and lawsuits regarding the legality of linking ads to specific user names (even though they had indeed clicked the “like” button and also in some fine print of the infamous “terms of service” had given their consent). One of the consequences of this research and the reactions it caused was for internet companies to limit publicity about the methods they use; as a result, experiments around ad intrusiveness are conducted in the dark.

Case 6: Aggregation of the strength of a social bond based on online behavior

Subject: the degree of overlap between friends on Facebook and friends in real life

Time: 2010 and 2011

Number of users: 789 users

The relatively small number of the group was recruited through relative advertising and participants had to declare honestly who their closest friends are in real life. It was the most formal of Facebook’s studies in the sense that it had received approval from the competent services and was implemented based on approved rules and methods (you see? not everything is done in the dark and behind our backs…)

The conclusion was that the more you interact with someone on Facebook, the more likely that person is to be a friend in your normal, non-digital, life. It is equally likely that you interact with them publicly, exposing your relationship in Facebook posts and also that you regularly exchange private messages.

It could very well be a first-year student assignment in any social sciences school and yet it became an object of interest for a top-tier company. Why? A first answer could be that 789 human guinea pigs voluntarily offered their interpersonal relationships to the anatomists of the internet, so they could play with them. A second: this research was nothing more than just a moment – a chapter or perhaps even a footnote – in a long process of analytical recording, classification and entry into computational models of social behaviors. A third: the real issue was to find a safe and valid way to identify the people with whom a user is associated, based on their online activity.

Case 7: The role of social networks in the spread of information

Subject: the way information spreads on Facebook

Time: 2010, during seven weeks between August-October

Number of users: 253 million (at that time, they were half of Facebook’s users)

Researchers randomly assigned the status of “shareable” or “non-shareable” to 75 million internet addresses. These addresses covered a wide range of content, from news to job offers, housing rentals, event announcements, and any kind of link shared by Facebook users. However, in cases where a link had the “non-shareable” status, it disappeared from the news feed and only appeared in direct messages exchanged by users or in posts shared exclusively with certain individuals. The researchers then studied the spread of links that had free circulation compared to those with restricted access. The goal was to determine whether censored information would find a way to spread.

As expected, the conclusion was that users tend to promote even more the information that is more intensively reposted by the majority of their online friends. It was also found that more distant friends are more likely to bring you into contact with new information, rather than close friends with whom there is a tendency to recycle the same information.

The fact is that with this experiment, at least to the extent we know, Facebook proceeded to a large-scale manipulation of content through censorship, achieving the manipulation of users. One of the concluding suggestions in the published report is characteristic: “the mass adoption of digital social networking systems potentially includes the ability for dramatic modification of the way individuals come into contact with new information”, a capability that extends to controlled information, censorship, and manipulation.

Case 8: Social influence and political mobilization methods

Subject: can Facebook encourage people to vote?

Time: 2010, before the midterm elections in the US

Number of users: 61,279,316, aged 18 and over

During the experiment, the test subjects had a “voted” button at the top of their page, along with information about the polling station they were voting for. It should be noted that users were unaware that they were participating in the research, but had the mistaken impression that election data was “playing” across the entire network. In addition, some of the participants saw the names of their friends who had clicked the specific button.

Facebook’s conclusion was that pressure from the close environment works. Users who saw the names of their friends who had clicked the button were more likely to vote themselves. When researchers cross-checked with electoral rolls, they found that users who had the “voted” button available were 0.39% more likely to vote, and the percentage increased for those who saw the names of their online friends who had voted. The percentages were modest, but Facebook claimed it managed to persuade 340,000 voters not to abstain.

With this experiment, Facebook entered the deep political waters for good. While reducing abstention seems to be a goal compatible with the electoral customs of western democracies, in this particular case the experiment had more to do with mass social control capabilities. As critics had correctly pointed out at the time, based on the issues of that pre-election agenda, Facebook could theoretically have placed the “voted” button and pushed only users who were in favor of restructuring migration processes to the polls, which the company and its founder and CEO Zuckerberg personally pressed for through the FWD.us organization. This organization is a “front” of Silicon Valley companies and systematically promotes changes to immigration laws and regulations, calling for stricter border controls and incentivizing highly skilled immigrants, in order to reduce labor costs through “competition” between local and immigrant skilled workers.

The way Facebook organized the experiment, hiding it behind a veil of secrecy, argues that it did not intend simply to reduce abstention: the 60 million users were unaware on the one hand that they were participating in an experiment and on the other that Facebook would cross-reference their data with electoral registers. Moreover, when the company was called upon to provide explanations, it refused, citing the protection of its users’ personal data privacy! Test subjects yes, but under Facebook’s protection no…

According to the researchers’ findings report, this particular experiment proved extremely promising and revealed their intention to repeat it: “The increasing availability of cheap and large-scale data from online social networks means that experiments of this kind can very easily be conducted in the field. If we really want to understand – and improve – our society, prosperity and the world around us [sic], it will be important to use these methods that determine which real-life behaviors are malleable through online intervention and influence”… A completely uncovered admission, with a ridiculous pretext, that the goal is online manipulation of real-life behavior.

Case 9: The spread of emotions through Facebook

Subject: does the emotional state of a user affect their online friends?

Time: 2012, over the course of three days

Number of users: 151 million

This is a precursor to the experiment on “emotional contagion” we mentioned in the previous issue (don’t believe the hype…). In this study, one million status updates were analyzed and categorized as positive or negative based on users’ posts. Then they investigated the positivity or negativity of posts made by the online friends of these users.

According to the findings, status changes resulting from something joyful pushed online friends to reduce their negative posts, and conversely, their negative posts pushed others to restrain their own cheerful expressions on Facebook. If you post something optimistic and good-natured on Facebook, at least one online friend will do the same within three days, and wouldn’t have done so if not influenced by you.

The results of the study could be considered conventional wisdom. Indeed, friends influence each other, and it happens that their mood changes solely due to the positive or negative stance of their friends. Except here we have a crucial difference: in the case of social media, friendships are digitally mediated and centrally monitored; their components are under the continuous supervision of the company. Therefore, the question is not simply whether “friends influence friends, positively or negatively,” but whether Facebook could manipulate users’ emotional state by exposing them only to certain posts from their online “friends.”

The irony is that in the report of findings, the researchers warned users not to attempt to manipulate their friends by orchestrating their posts appropriately: “The results show that Facebook posts have the ability to influence subsequent posts by friends. However, we would not advise Facebook users to express inauthentic positivity or suppress the expression of negative emotions in order to keep their friends satisfied.”

These nine cases (ten, including the “emotional contagion” experiment) are certainly not the only ones. There are still many experiments and studies that Facebook has (or was forced to) announce: are fan preferences sticky? (Answer: yes.) How many user statuses have political content? (Answer: less than 1%.) Can it be determined whether a user is lonely based on their activity on Facebook? (Answer: yes.) How close do you live to your online friends and is it possible to locate your geographical position based on their addresses? (Answer: approximately.)

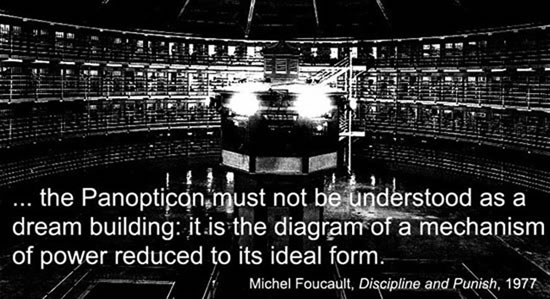

It has been counting decades now, but it remains one of the most common and easy criticisms, that the modern world has been transformed into the totalitarian society of Orwell’s 1984. The reference to Big Brother has become such a cliché that eventually awareness was dulled that reality can always surpass the worst literary nightmares. In the dystopian Oceania, the basic motif is not that of a monstrous mechanism that watches everyone, revises history and language, and imposes a dense web of rules and orders, but of such a mechanism that becomes the absolute tool of hyper-determination of citizens’ lives, not only at the level of their actions but to the depths of their most intimate feelings.

Today, the megamachine of the cybernetic space brings this dystopia to the threshold of its realization. The nightmarish scenario is not that of a panoptic mechanism that monitors, records, classifies, and processes the enormous volume of digital data that hundreds of millions of people have willingly or unknowingly surrendered. To the extent that this has been achieved, the crucial question is whether and how this immense power can be used to directly and specifically manipulate the lives of citizens. The masters of cyberspace do not care to know everything about us, because we are already, at least digitally, terribly transparent! What interests them and what they are intensively experimenting with in this direction is the general direction and control of real life…

Harry Tuttle