a manifesto for cyberspace…

“Oh, you governments of the Industrial World, you who look like exhausted and obsolete giants of flesh and metal, I come from Cyberspace, the new home of the Mind. On behalf of the future, I call upon you, you of the past, to leave us alone. You are not welcome among us. Where we gather, you have no sovereign rights.

Since we do not have an elected government, nor do we intend to elect one, I address you without possessing any authority greater than that with which freedom itself speaks. I proclaim the global social space we are building as inherently independent from the various forms of tyranny you seek to impose upon us. You have no moral right to dominate us, nor do you possess methods of enforcement with which you could truly intimidate us.

The power of governments stems from the consent of the governed. We have neither asked you for our consent nor have you given it to us. You have not invited us. You know neither us nor our world. The cyberspace does not lie within your borders. Do not think that you can build it as if it were any public work. You cannot do it. It is a kind of natural energy that develops through our collective actions.

You have never participated in our great discussions, nor have you created the wealth of our markets. You do not know our culture, our customs, and our unwritten codes of conduct that already provide more order to society than all the measures you can impose.

You claim that there are problems within us that need to be solved. You use this claim as a pretext to invade the areas of our own jurisdiction. Many of these problems don’t even exist. And where there are indeed conflicts, where there are errors, it is our job to identify them and deal with them in our own way. We are writing our own Social Contract. This form of governance will emerge from the conditions prevailing in our own world, not in yours. Our world is different.

The cyberworld consists of transactions, relationships, and thought itself, arranged within the network of our communications like a standing wave. Our world is a world that is simultaneously everywhere and nowhere, but in any case, it is not where bodies reside.We create a world where everyone can enter, without privileges and prejudices, that stem from perceptions of race, from economic power and military strength or from place of birth.

We create a world where everyone can express their beliefs anywhere, no matter how marginal they are, without fear of being silenced or forced to conform to certain standards.

We are not concerned with your legal concepts of ownership, expression, identity, and movement. All of them are based on matter, but matter does not exist here.

Our identities have no bodies, and thus, unlike you, it is not possible to impose order upon us through physical coercion. We believe that our form of governance will emerge from our personal principles, enlightened self-interest, and the common good. Our identities may be distributed across many of your jurisdictions. The only law that is universally accepted by all of us is the Golden Rule. We hope that on this basis we will manage to find our own solutions. However, we cannot accept the solutions that you are trying to impose upon us.

In the U.S., you have created a law, the Telecommunications Reform Act, which contradicts the Constitution and constitutes an offense against the dreams of Jefferson, Washington, Mill, Madison, DeTocqueville, and Brandeis. With us, these dreams must be reborn.

Your own children terrorize you, being indigenous to a world where you will always be immigrants. Because you fear them, you entrust your parental responsibilities, which you tremble so much to undertake, to your bureaucracies. In our world, all emotions and expressions of humanity, from the crudest to the most angelic, constitute an inseparable whole, the global conversation between bits. We cannot separate the suffocating air from that which allows birds to fly.

In China, Germany, France, Russia, Singapore, Italy, and the U.S., you are trying to protect yourselves from the freedom virus by building prisons at the borders of Cyberspace. These might stop the spread of the virus for a short while, but they won’t last long in a world full of media that operate with bits.

The increasingly obsolete information industries will try to stay alive by proposing laws, in America and elsewhere, which would secure copyright of the word throughout the world. According to these laws, ideas are nothing else but an industrial product, no more noble than something like pig iron. In our world, anything that the human mind can create can be reproduced and shared infinitely and at no cost. The global circulation of information no longer needs your factories.

These increasingly aggressive and colonial measures that you are taking place us in the same position as those precious lovers of freedom and self-determination who had to oppose the demands of distant and uninformed powers. We must declare our virtual selves inviolable against your sovereignty, even as we continue to accept the power you hold over our bodies. We will spread throughout the entire Planet so that no one can capture our thoughts. We will create a culture of the Mind within Cyberspace. May this be more humane and just than the world that our governments have created so far.»

Davos, Switzerland

February 8, 1996

In 1995, the year of the first full commercial deregulation of the Internet occurred, whose infrastructure until then had been under the supervision of the American state. A year later, in early 1996, the American government proposed (and Congress overrode on February 8) a legislative act, the so-called Telecommunications Act, aiming to regulate the new landscape that would emerge in the telecommunications sector following the opening of the Internet. Essentially, this law aimed to create a competitive business environment around the Internet and its infrastructure, into which any company could enter without many difficulties and obstacles. The text we present above, as one of the first reactions against the law, was released on the very day of its override, under the emphatic title “A Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace.” Written by John Perry Barlow (former member of the Grateful Dead) and evidently intending to refer to the American Declaration of Independence (from British sovereignty) of 1776, it resembles almost like a manifesto of cyberspace. It gives the impression (written indeed by an artist) of a grassroots resistance against attempts to enclose the Internet, which until then had constituted a space of freedom, a space of “digital commons.”

Although few today would share his haughty tone, this particular text still encapsulates a cluster of arguments that constitute the basic defensive line against whatever is perceived from time to time as an attempt to dismantle or restrict freedom on the internet – a cluster that has become established as the “cyberlibertarian ideology”1. When such arguments are combined with a series of “subversive” technological products and practices—such as the open-source software “movement,” hacking, cryptocurrencies, and encryption in general, piracy, peer-to-peer production and sharing systems, etc.—one gets the impression that a kind of guerrilla war is raging between the “people of the internet” and the major corporate and state interests. Not surprisingly(?), a large part of the left (even the far left) appears eager to take a stance in this dispute—predictably in favor of whom. In some cases, it has not only adopted cyberlibertarian arguments but has also gone further by endorsing the hands-on capabilities of these “guerrilla” internet practices and technologies. We have reservations both regarding the degree of affinity between the left and the cyberlibertarian ideology and concerning what the real stakes of this “dispute” are. Reservations that could have also emerged within the left itself, had it taken the trouble to observe that the cyberlibertarian ideology is an article of faith for individuals such as Sergey Brin (co-founder of Google) and Facebook’s Zuckerberg.

the historical contributions of cyberlibertarian ideology

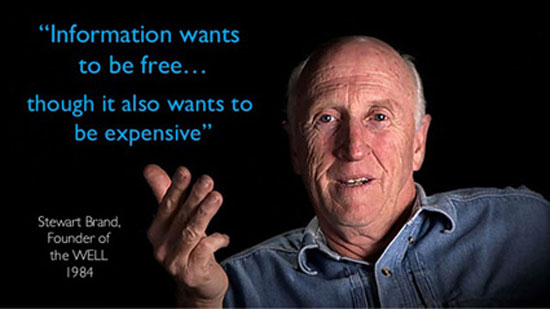

The author of the Manifesto for Cyberspace is not some random figure in the history of cyberlibertarian ideology. Along with some other individuals, such as Kevin Kelly (founding editor of the tech magazine Wired) and Stewart Brand (publisher of the legendary Whole Earth Catalog, a bible of the American counterculture of the 60s and 70s), he was a pioneer of this ideology, whose roots trace back well before 1996, already to the 1960s. Nor is it coincidental that he was also a member of a rock band of that era. The non-random aspect here lies in the fact that the core of this ideology was essentially first expressed and developed within the diffuse libertarian climate that prevailed in the countercultural movements of those decades2.

It is perhaps well known that the movements of that era did not constitute a cohesive front with uniformity regarding their purposes and the means to achieve them. However, behind their diversity, they shared a common core of concerns, which was primarily expressed as dissatisfaction toward what until then had been presented as the model of a happy life for an average American—because it presupposed integration into bureaucratically organized hierarchies, jobs requiring the performance of dull and repetitive tasks, reduced autonomy, and in general whatever could be described as alienated labor. The rejection of the “model-for-the-happy-American” often went beyond mere words. On one hand, political groups, following the rationale that “we must put our principles into practice,” attempted to organize themselves on anti-hierarchical structures. On the other hand, a rather significant communal living movement emerged, often based on the idea of returning to nature, within which life was supposed to be the opposite of work routines and obedience to mechanical rules. Moreover, all this was often accompanied by hedonistic lifestyles that scandalized the traditional conservatism of the “happy American” who swore by the triad of work-home-family.

Less known, however, is the existence of a rift between two tendencies of the 1960s counterculture, which may never have reached the dimensions of an open schism with the ensuing ideological hostilities, but which proved a posteriori to be of crucial significance for our subject. One of these tendencies was expressed in what later came to be called the New Left, encompassing a multitude of political groups with affinities to the broadly understood left, yet not necessarily identifying with any orthodoxy, and often opening the discussion towards new problematics (e.g., concerning race and gender). For all these groups, it was self-evident that the path towards overcoming alienated labor and, in general, all forms of separation necessarily passed through practices of collective organization and political struggle in the public sphere. Characteristic of the second tendency was precisely the rejection of such practices. In the eyes of many who found an outlet in communes and in nature, the traditional forms of political action (including those of the New Left) were bankrupt and from the outset suspect as conducive to oppressive hierarchies. As an antidote to such dangers, what they prioritized was not only a return to nature but also a return to the self itself, a turning inward to explore individual consciousness, as a necessary step towards overcoming any internal fixations and internalized authoritarian tendencies.

The seemingly paradoxical thing about this communal tendency was that their desire to return to nature did not imply any universal rejection of technology. On the contrary! In a DIY logic of self-utilization, they needed “access to tools” (as the Whole Earth Catalog put it) that would facilitate and accelerate self-exploration (e.g., psychedelic substances for exploring consciousness) and their degree of self-sufficiency (with all kinds of gadgets of the era). Tools that a democratized technology could and should produce and make accessible to everyone3. What is even more impressive, however, is that they found a kind of ideological legitimation in theories that were born from within the bowels of the military-industrial complex: systems theory and cybernetics. A key characteristic of these theories that exerted appeal to these communal communities, already positively predisposed toward holistic perceptions, was the fact that they provided a model of anti-hierarchical organization where every node of the system can communicate with any other on an equal basis, and where any resulting structure does not impose itself from above but emerges through the action of individual nodes. Regardless of whether this perception truly corresponds to the reality of cybernetic theory, what matters is that it was thus interpreted at that time by those groups. It is most likely, of course, that they were unaware of the sources of systems theory within military laboratories. However, cybernetics had already escaped from engineering laboratories and had become a fairly widespread intellectual model that was “applied” to the most diverse scientific fields (even anthropology, mainly through the work of Gregory Bateson).

For some years, the communal tendency evolved in parallel with that of the New Left. However, their trajectories were quite different. While the movements of the New Left accumulated defeats, already from the 1970s, the techno-libertarian tendency, although in practical terms it also experienced a decline with the dissolution of many communes, managed to remain alive at the ideological level. Ultimately, it became dominant, especially with the spread of personal computers from the 1980s and subsequently with the spread of the internet. Finding new inspiration in the theories of Marshall McLuhan, who saw in the new media possibilities for empowering individuals and the spontaneous emergence of a virtual demos, beyond the control of corporations and states, they proceeded to shift their techno-libertarian ideas into purely informational contexts. And as a result, the cyber-libertarian ideology was born: the new digital media, with their inherent interactive capabilities, allow everyone equal participation in a space of freedom that must be left free from external interventions—and here, mainly state regulations must be understood4.

the revival of liberalism in the 1970s

However, the reason why neoliberal ideology managed to survive and ultimately prevail needs an explanation. In our view, the defeat of the New Left and the dominance of liberal ideology are not two merely parallel developments, but complementary ones. And the connecting link that unites them is called the revival of liberalism. Initially as economic orthodoxy in the 1970s, subsequently as political practice from the 1980s onwards (mainly in the U.S. and Britain initially), and – most importantly for the purposes of this discussion here – as a social ideology throughout all these decades until today.

As an economic doctrine, liberalism never completely disappeared, but in any case remained a rather marginal current during the post-war years in the West, always in the shadow of the then-dominant Keynesian policies. It had to wait until the 1970s to re-emerge dynamically, as a real alternative, back in the foreground5. Among other things, it had the following weapon to offer into the hands of employers: a response to a generalized wave of work refusal6. Discomfort with alienated labor was not expressed only through actions on the central political stage or through communal withdrawal. There was also a form of reaction equally (if not more) worrying for businesses in a large part of the Western world, and it had to do with the very workplaces. Complete refusal to integrate into the workforce, low-quality work, continuous absences from work, labor sabotage, and persistent strikes: these were some of the ways in which an entire generation expressed its alienation from alienated labor—and from its morality.

The initial reaction of the bosses was traditionally predictable: concessions in terms of job security, higher wages, etc. Realizing, however, that even these concessions could not reverse the wave of work refusal, some of them (the more “visionary” ones) shifted the game to the heart of anti-labor rhetoric and played the card of granting increased “autonomy” to workers; but through the (neo-)liberal prism of individual self-realization. We reproduce an excerpt from the Red Pages, issue 4, “The refusal of work in France… and the new spirit of capitalism”:

“But the real new idea was the recognition of the value of the demand for autonomy, and even more so that this became the central value in the new industrial, and more broadly capitalist, arrangement.

…

With a remarkable political reversal, autonomy was exchanged for security. The employers’ struggle against unions and their turn toward greater individual autonomy and individualized pay was accomplished through appropriate means—namely, by changing the organization of labor and increasing productivity.

…

Just as occurred with the students’ demand for autonomy, here too autonomy was understood as a condition concerning individuals (who are less tightly controlled by hierarchy) and as a condition of productive units (departments, that is, that are now treated as independent units and independent profit centers; or the development of subcontracting). The world of work would evolve into a field composed of individual entities, interconnected with each other through some kind of network.”

And if the liberal rhetoric of self-realization managed to take hold within workplaces, it succeeded equally outside them: through the incorporation into the capitalist circuit of various lifestyles and marginal artistic/aesthetic currents, reinterpreting them naturally as individual choices that allowed everyone to “find themselves.” It is not difficult to see how cyberlibertarian ideology clicks with the “new spirit of capitalism.” Autonomy, self-realization, focus on the individual, connections/relationships in the form of networks: a common vocabulary within which cyberlibertarians would feel like fish in water. With the extra bonus that they could maintain a (pseudo-)sense of “marginality” – as just another lifestyle.

Especially for the information technology sector, another development has also gained significance here. The reorganization of production into more automated and flexible models, through processes such as outsourcing and modularization7, made it clear that information technologies would play a central role. As would the category of highly specialized workers who would carry out this restructuring—and who, initially, were expected to enjoy favorable treatment. The celebration of this new category of workers found its ideological expression in the then (late 1960s, early 1970s) emerging theories of post-industrial capitalism. Think tanks and intellectuals (such as Daniel Bell, with his book The Coming of Post-Industrial Society) viewed the transition toward a new capitalist model—as organized primarily around the provision of services—almost as a natural law, where “knowledge” and “thinking” (rather than manual labor) would become the driving forces. And where the most significant class of workers would be the so-called “knowledge class”; that is, scientists, engineers, and managers8.

the digital commons

After all this, what then does cyberlibertarian ideology express? Our humble view is that it has little to do with any kind of defense of digital commons, as it is often presented or even wishes to present itself. It is more a mixture of a complacent technological determinism, expressed in cyber-informational terminology, and an extreme version of atomistic liberalism. And from this perspective, it is indeed an ideology, in the narrowest, Marxist sense of the term: false consciousness in the service of the capitalist paradigm shift that began in the 1970s. It is the defeat of the movements of that decade, inverted and served as a victory.

One objection that may arise at this point is that cyberlibertarian ideology does not necessarily relate to the insurgent practices of defending digital commons, such as open-source licenses, hacking, cryptocurrencies, etc. We cannot address all these practices here, but we will focus on two current examples.

First example: there is a plethora of open-source licenses, graded according to how strictly one wants to enforce the requirement for the code to remain open through various stages of processing and modification. Broadly speaking, the stricter a license is considered, the more likely the code is to remain open. Currently, the strictest are considered to be the so-called GNU GPL licenses, inspired by the well-known Richard Stallman. Two points are worth emphasizing here. First, even in the GNU GPL licenses (we repeat: the strictest), there is no clause that prevents either commercial or even state/military use. Most servers around the world run on open-source code (or its variants). As do Google’s smartphones. Very likely, as does the guidance system of a drone’s missiles…

Second point, initially in the form of a question: has anyone noticed a movement that extends the concept of “open” to the material infrastructure of information technologies, an “open hardware” movement;9 The absence of such a movement is neither coincidental nor a simple oversight. Stallman himself insists that the concept of ownership at the level of “ideas” must remain separate from the same concept at the material level. The reasoning he uses to justify this distinction is slightly “distorted,”10 but there is something else we would like to focus on. Whether he is aware of it or not, Stallman, with this separatist logic, essentially reproduces one of the fundamental pillars of cyberlibertarian ideology: that “ideas” are something special and as such deserve special treatment. More prosaically and “cynically,” he reproduces the distinction between manual and intellectual labor, thus reserving a more upgraded position for those who work “intellectually”; for those who are members of the “knowledge class” (isn’t this also called guild mentality?).

Going one step further, another even more worrying consequence emerges. When they want to deal with the issue of commercial exploitation, open source advocates usually put forward the argument that although it may not be excluded, it essentially becomes unprofitable due to the strict requirements of the license. Practice has shown that this is not exactly what happens. In a (always liberal) competitive environment, whoever can reap profits from something that circulates freely is the one who has a critical mass, both in terms of hardware infrastructure and in terms of workforce – where, as we said, the issue of “openness” does not arise. Or, in other words, whoever is already strong11. From this perspective therefore, open source software not only does not protect any digital commons, but essentially constitutes a specific type of business model that has the ability to transform these initially common goods into quintessential commercial products; without returning anything to the original creators. Instead of defending digital commons through open source licenses, shouldn’t we therefore also be talking about a process of digital primitive accumulation?

Second example: the debate over net neutrality. Technically speaking, the issue here concerns whether information packets circulating on the internet should be treated equally (as is currently the case) or whether some of them should be given priority, possibly depending on their content. In the latter case, for example, a video service provider could pay network owners more money so that they prioritize its videos to reach subscribers faster. The dominant public image formed around this debate has positioned the large corporations on one side and the rights of the “internet people” on the other, with various cyber-libertarians, such as those from the Electronic Frontier Foundation (one of whose co-founders was Barlow), presenting themselves as their defenders.

However, not all companies support the abolition of net neutrality. Google is also on the side of the “people” here. Due to its sensitivities? Not exactly. Until now, Google, like all content providers, pays network owners a specific rate based on the volume of packets transferred. However, to the extent that these packets contain commercially exploitable information (e.g., personal data usable for advertising purposes12), they have begun to acquire an additional value that is not linearly correlated with their volume, but now also with their content. Therefore, the debate over net neutrality also has this dimension: to what extent network owners will be able to claim a share of the profits “hidden” within internet packets, or whether content providers will remain privileged, without having to compete with each other for access to the internet’s “highways.” For cyber-libertarians, however, the issue remains an abstract concept of freedom.

If something becomes evident from the above examples (at least in our eyes), it is this: disputes around the internet often have aspects that have less to do with some kind of “freedom” in it and more with the attempt of the new capitalist model to find new balances. Just as with the major players trying to secure as privileged a position as possible and find new business models. We believe that the cyberlibertarian ideology, although we may share certain concerns with its adherents, cannot (and never had the purpose) to serve as a bulwark against digital enclosures. And this inability of it is the best version of the problem.

Because in the worst case, it functions precisely as an ideology, turning its followers into a tail of this or that interest group. Even when they deeply believe the opposite13.

Separatrix

- See the article by David Golumbia “Cyberlibertarianism: The Extremist Foundations of Digital Freedom” and James Boyle’s speech “Foucault in Cyberspace”. ↩︎

- For more historical details, see the article by Barbrook and Cameron «The Californian ideology», as well as the book by Fred Turner «From counterculture to cyberculture: Stewart Brand, the Whole Earth Network, and the rise of digital utopianism». The historical facts we present here refer mainly to the U.S.A., since it was there that the cyberlibertarian ideology was born and only later was exported to other countries. ↩︎

- The famous poem by Brautigan, «All Watched Over By Machines Of Loving Grace» is highly indicative:

«I like to think (and the sooner the better!)

of a cybernetic meadow

where mammals and computers live together in mutually programming harmony

like pure water touching clear sky.

…

I like to imagine (and the sooner it happens the better!)

a cybernetic meadow

where mammals and computers will live together in mutually programmable harmony

like crystal clear water touching a clear sky. ↩︎ - The contradictions of cyberlibertarian ideology are not rare. On one hand, the new media will legally lead to the decline of large power structures, such as states; on the other hand, they must be protected from external interventions, such as those of the state—so their dominance is not so legal after all… On one hand, ideas and data must circulate freely and openly in cyberspace; on the other hand, we condemn privacy violation practices… But if digital data must be open, why shouldn’t personal digital data also be open and accessible…? The fetishism of information, a component of this ideology, can hardly provide convincing solutions to such contradictions. ↩︎

- We will not dwell on this here, but simply note that neoliberalism had certain essential differences compared to classical liberalism (e.g., the recognition of the centrality of the state as overseer of the proper functioning of the market). For the adventures of neoliberalism, see Red Pages, issue 0.3, “The Birth of the Neoliberal in the 30s”. ↩︎

- See Red Pages, issues 2,3,4, “Hepa: the uprising against work – The refusal of work”, “Porto Marghera (Venice): the refusal of work”, “The refusal of work in France… and the new spirit of capitalism”. ↩︎

- See Red Pages, issue 5, “The restructuring of work – Tertiary sectorization…”. ↩︎

- See the second chapter in Dyer-Witheford’s book, «Cyber-Marx: cycles and circuits of struggle in high-technology capitalism». It has historical interest here: however paradoxical it may sound, theories about post-industrial capitalism have some roots in left-wing critiques of the Soviet Union, mainly through Trotskyist circles! An example is Burnham’s work, «The managerial revolution» (which had already been published in 1941), in which he attempts to describe the rise of a ruling bureaucratic elite in the Soviet Union, a tendency that could also be observed in other countries, such as the U.S.A. during the New Deal era. Daniel Bell had dabbled in Trotskyist circles in his youth and probably had such analyses in mind. He therefore took them… and reversed them. Bell’s “knowledge class” is an inverted version of Burnham’s bureaucratic elites! ↩︎

- Open hardware refers to the opening of designs (design, somewhat like the architectural plans of a building), not the physical hardware devices themselves. ↩︎

- See John Pedersen’s essay, «Free culture in context: property and the politics of free software», who had direct communication with Stallman precisely on this topic. It can be found at https://commoning.wordpress.com. ↩︎

- Something that, by the way, also resembles the formally civic-liberal disconnection of politics from economic equality, with the known consequences that economic inequality can have on the possibilities for political equality. ↩︎

- See the relevant information provided in the report of the Game Over event “The end of privacy?: self-exposure and the commodification of personal data”. ↩︎

- For the darker sides of free software, see also Cyborg, issue 6, “free” as in “free software”: a small tribute to free software. Specifically for hacking, see Cyborg, issue 4, “Hacking as ideology”. ↩︎