One would assume that biohackers are a marginal cosmopolitan phenomenon, some “geeks” here and there. Indeed, numerically speaking, biohackers may be few in number, for now. Ideologically, however, biohacking indicates something mainstream. According to a definition:

Biohacking is a name that sounds crazy for something that is not crazy at all: the desire to be the absolute best version of ourselves.

Before being swept away by the second, synthetic part of the term, “-hacking”, thinking it refers to some “geeky screwdriver-wielding folks”, one needs to pay attention to how “the absolutely best version of ourselves” can be understood in 21st-century conditions.

The first and historically documented aspect is that this desire belongs to the very broad and general circle of desires for “self-improvement” and “self-care”, which have concerned postmodern societies since the 1970s. From gyms to hygiene, and from plastic surgeries to the chemistry of “performance enhancement”, most of this bundle of social practices has revolved around a central idea: eternal youth. In the name of “performance” (in its various forms, from sexual to intellectual), the historical content of “self-care and self-improvement” for about four decades has been anti-aging.

Within this very broad, established, and socially entrenched historical cycle of social practices, biohacking (with its “crazy” name…) comes to add or highlight something specific: the concept of the “optimal version of oneself.” This concept of the “optimal version” is borrowed from software versions 1.0, 2.0, 3.0, etc., each representing an improved iteration: biohacking, as a concept, originates primarily from the continuous upgrading of computing machines.

In other words, the contemporary technological environment is the conceptual setting of a new historical phase of “self-improvement and self-care.” Within this context, hacking is nothing more than a do-it-yourself approach to the “self-disposition” of this desire (for care and improvement…). As for the “bio”? It refers to the orientation: self-care and self-improvement through biology and biotechnology. Anti-aging remains a constant reference goal. But it is no longer alone. Self-care and self-improvement are now also defined by the “capabilities” promised by new technologies: it’s such a thing (care and improvement…), for example, to open your doors or your computer with a mere thought…

Although biohacking has emerged from the previous historical phase of “self-care” much like Athena sprang from Zeus’s head, there is a strategic shift: from maintaining youth (or at least, the image of it) to enhancement. From the fixation on the state of “myself when I was young”, an approach that looked nostalgically backwards, to the fixation on “the continuous upgrading of myself”, an approach oriented towards the (mechanical) present and future. In the phase of biohacking, past youth is not the ideal, as it is technologically poor and/or outdated. There is a different “youth” that is sought, an idea of “youth” that looks forward: the continuous adaptation to the possibilities of technological self-enhancement.

Biohacking appears as a current that has started from “the bottom”; we are not sure that this is true. It has a mutually reinforcing relationship with two slogans. Science for everyone, and biotechnology for everyone. There is in this “popularity” a clear imitation (?) of computer for all, an American youth / student initiative in the ’70s, from where the idea and the demand first sprang, and subsequently the construction of personal computers. (Let us remember that at that time computers were huge in size and only for industrial or/and bureaucratic use).

Science for everyone does not propose revolution in educational systems! This is interesting, because it grasps “science”, as knowledge, not from its beginning but from anywhere. The linear development of scientific knowledge through long-term education has no place in this rhetoric. One would say that such an approach is “anti-scientific”, but this is corrected if one sees what it is about. Science for everyone is rather an encouragement towards the great mass of citizens to participate in various crowdsourcing programs. It mainly means voluntary collection of observations / data from everyone (on health issues, social services, environment, but also astrophysics). This entails, of course, mass familiarization with the “dat-ification” of reality, and in white the transfer of this accumulation to algorithm manufacturers.

Biotechnology for everyone, which could be considered a subset of science for everyone, appears as a step further from participation in (simple) recording and data collection. It also includes experiments of biological content. One can find basic equipment being sold on the internet (often second-hand) at affordable prices, especially if some group of ambitious and curious experimenters pays, with a grant or with crowdfunding.

The range of these diy “experimenters” is large (in reality: unknown). Usually professionals also participate in these groups, recognized knowers with diplomas that is. The thing starts from simple observations and reaches various versions of biohacking. Either purely biological content (for example: controlling the synthesis of various foods), or with the mixture of biology and cybernetics. Experimental implants of microcircuits are included in this repertoire.

The advocacy in DIYbio revives the libertarian arguments of the past: the right of access (to biotechnologies…) for everyone, anti-hierarchy, collectivity and communitarianism, anti-commerciality, etc. Moreover, the protagonists of this movement claim that they have stricter “bio-ethical rules” compared to corporate research centers. It is certainly a matter of who controls what. On the other hand, this seems rather answered: as the technological infrastructure, the machines that is, evolves, such “old” ones become cheaper, even various kinds of machines / biological analyzers. Consequently, they become accessible (from a cost perspective) to a market that can be characterized as “amateur”. If one adds the cost reduction in DNA “analysis”, one would conclude that the spatiotemporal boundaries of DIYbio are at the perimeter of official biotechnologies, mainly as a process of social legitimation.

There is, of course, also a dangerous side. A form of bio-terrorism could emerge from DIYbio. Or, equally likely, such amateur laboratories could be targeted by authorities; although genetically modified viruses that could be used as weapons are well-guarded military secrets.

This targeting has happened at least once. It failed. But it is interesting, because the person accused as a bio-terrorist could be considered a pioneer in some aspects of biohacking; although he has not pursued such a title.

“A small step for the artist, a leap for the headphone industry!”

c.a.e.

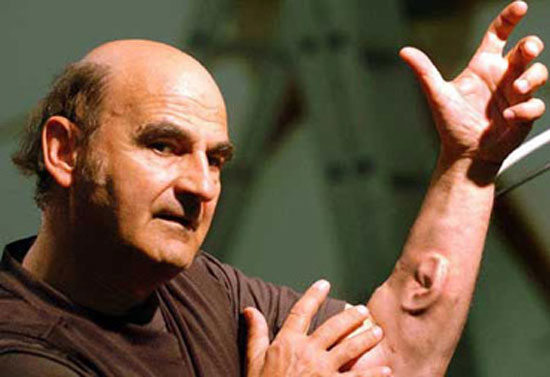

On the afternoon of May 11, 2004, Steven Kurtz called the American “emergency services” saying that his wife, Hope, was not breathing. The hospital arrived along with a patrol car, but Hope had already died. However, the officers discovered something else inside the house: a biological laboratory, with a microscope, a centrifuge, and bacterial cultures in petri dishes. The windows were covered, and on the shelves they discovered books with titles such as “The Biology of Doom” and “Spores, Epidemics and History: The History of Anthrax.” It goes without saying that the FBI was mobilized, and whatever specialists in biological terrorism the US had at their disposal. A few months later, in the summer of 2004, Steven Kurtz was summoned to the prosecutor to testify as a defendant accused of illegally possessing two types of bacteria, as well as for mail forgery. These charges could send him to prison for up to 20 years.

Fortunately for Steven Kurtz, he was known. He was a professor at the State University of New York in Buffalo and, above all, he was a member of the New York art/activist group Critical Art Ensemble. Both he and his wife were known, at least in the avant-garde scene of New York, to use biological or even chemical elements in various installations of theirs.

The mobilization of the artistic circles of New York as well as the major mainstream American media did not spare Kurtz from the judicial ordeal, which lasted for several months; however, they saved him from a conviction that seemed certain.

A conviction that would be certain if he were Arab-American, or just Arab, or Muslim. What could amateur DIY biolabs experiment with? Not with anthrax or smallpox. But it’s not hard to find samples of some flu virus that has been declared particularly deadly, if the epidemic has spread. Obviously, unless he has the alibi of artistic avant-garde, the ten commandments of the good biohacker won’t save him… Especially if it’s urgent to find “dormant bioterrorist cells”.

So, this current bipolarity does have some significance. In recent years, various aspects of biohacking and bioscience for all have essentially become fields of “artistic interest.” Various performances and exhibitions, under the general title bio-art, objectively function as agents of Paradigm Change. 1 One could conclude that this is, from an artistic perspective, an attempt to impress; and from a political perspective, a (not premeditated…) move to bring biotechnologies into pop culture. On the other hand, other aspects of the same technologies are considered dangerous—even as “weapons of mass destruction.”

On one hand, terrorism (war), and on the other, artistic avant-garde, define the field we could call: the new bio-informational (capitalist) paradigm, the new brave world, and our adaptation to it, through our enhancement/improvement. Possibly, this is a transitional period: between the megadanger (bioterrorism) and the megawonder (art), the field is filled with middle-brow risks and middle-brow aesthetics: the implanted chip is not only “functional”… it is also “beautiful”! A small deformation of the skin, the suggestion of a small subcutaneous “thing,” which can and should be displayed also as the aesthetic of electromechanical “enhancement”…

Ziggy Stardust

- Although Athens is provincial to stand at the international center of such events, artistic exhibitions have not been lacking, albeit without attracting great attention. In February 2006, for example, the international exhibition In Vivo In Vitro was held in spaces of the school of fine arts, with the explanatory subtitle: art in the age of biotechnological revolution. As a new genre in these parts, Bio Art needed some presentation:

…Bio Art is the art that uses biotechnology as a medium, but also as a form of interventionist commentary: Cultivation of living tissue, morphological modifications, bio-mechanical constructions…. Others use artificial life (artificial life, that is, simulation of the behavior of the biological entity using special algorithms in the program), or artificial intelligence, or even a combination of biological and technological entities… (More reviews available at http://biotechwatch.gr/BioArt).

In the summer of 2009, the Greek transplant company co-organized in Athens a traveling around the world private exhibition entitled Bodies Revealed: a parade of human bodies (“of unknown origin”…) preserved in various “pieces.” Although thematically it did not belong, at first glance, to the futuristic environment of other bioart exhibitions and could resemble more a 3D “anatomy lesson”, the famous painting by Rembrandt, the artistic relevance of such an anatomical “gaze at the body” places such exhibitions in the account of its transformation. (More reviews on the origin of the corpses available at http://aboutbodies.blogspot.gr).

Recently, at the end of 2016, at the roof of the Onassis Foundation, an exhibition was held entitled: Hybrids: At the boundaries of art and technology. ↩︎