Saying that capitalist relations of production and consumption are dominant, essentially across the entire planet by now, constitutes a truism. This is an obvious observation, at least for those who have not been convinced by the, ultimately fatal, theories of the “end of history” and “self-transcendence of capitalism,” which a few years ago had become fashionable (and sometimes are still trotted out, particularly the latter). One does not need to be “left” or “right” to accept this observation as a simple reflection of reality. It suffices at least to be serious and not make a living from producing ideology…

Saying that reproductive relationships, both of labor and of nature, have now also been largely subordinated to capitalist norms may not be equally self-evident. Yet even if the observation regarding capital’s dominance remains only at the level of production and consumption cycles, there is a very real political risk. Insofar as such observations are articulated as abstract generalities (“we had capitalism two centuries ago, we have capitalism now, things have remained the same”), they risk losing their footing at any moment. Not because they are inaccurate, but because they are “lazy,” failing to grasp crucial transformations in certain aspects of capitalism. Capitalism may not have transcended itself, but it has not remained unchanged throughout its historical trajectory. If anything, its course has certainly shown that it contains an extraordinary potential for mutation whenever it faces the threatening prospect of its own collapse. And as we know, when one sows intellectual laziness, one reaps political failure. The difference being that the consequences of such failure are not merely intellectual and spiritual, but often paid for in blood (even literally).

In our humble opinion, the time for intellectual laziness and theoretical acrobatics has passed irretrievably (if it ever existed). The critical understanding of the current phase of capitalism – and particularly its technical composition – along with its genealogy and the historical possibilities it opens up for the future, constitutes an urgent task that has already been delayed.

Easy in words, difficult in practice. Difficult, because generalized complacency, often disguised as techno-enthusiasm (or as adherence to a “Swiss” neutrality of equal distances in relation to the use of technology), does not help to feed the relevant discussion with the necessary theoretical tools. In any case, such a tool that has proven useful in our analyses is also the term “change of capitalist paradigm.” Because, as a term, it runs the risk of either being misinterpreted or even mystified (it may sound somewhat heavy-handed), we judge that some additional (and in any case not final) remarks may perhaps help to clarify it 1.

about epistemological paradigm

Starting from the term “paradigm”, a preliminary clarification that needs to be made is that it does not originate either from any economic theory or from political science. It is not a term that has found a somewhat established place within the conceptual universe usually mobilized for the study of capitalism. For this reason, therefore, it does not possess a very specific, “technical” meaning, such as, for example, the concepts of capital, surplus value, or (real / formal) subsumption. Without this, of course, meaning that, based on our own conceptualization (and as will become clear in the following), it does not have some relation to these more established terms. This particular term, then, draws its origin from epistemology and more specifically from Kuhn’s classic work “The Structure of Scientific Revolutions” (first edition in 1962).

The somewhat loose use of the term, even by Kuhn himself, provided an opportunity for systematic criticism to be directed against him, primarily regarding the ambiguity it seemed to contain 2. Nevertheless, it is possible to reconstruct with relative clarity the core of Kuhn’s argument that led him to introduce the term “paradigm.” The significance of Kuhn’s book lies in the fact that it served as the catalyst for the age of innocence within epistemological circles to finally come to an end; 3 and indeed at a time of rapid techno-scientific developments—or perhaps precisely for this reason (the destructive potential of nuclear energy had already sown suspicions regarding technological “progress”). Speaking somewhat schematically, the pre-Kuhnian innocence consisted in the absence of a critical reflection on the historical development of science. The dominant perception until then viewed the evolution of science as a linear path of knowledge accumulation. According to this view, every scientific theory must (and does so in practice) be examined in a strictly scientific manner (“rationally” and experimentally), its weak points must be identified (“objectively”), and it must be enriched so as to be able to include in its explanation whatever was previously unexplainable. There are no gaps in this development. It is the “natural” course of the human spirit toward continuously improved knowledge, regardless of environment, conditions, and contexts.

According to Kuhn’s analysis, this is a simplistic perception that does not correspond to historical reality – or, in more political terms (which Kuhn himself does not use), it is an ideological reading of the history of science. Science, when studied historically, did not evolve in this way. On the contrary, what can indeed be observed is the following: For long periods of time, a scientific field operates using certain basic theoretical tools. All involved scientists use these tools and often, phenomena that cannot be explained are simply ignored. However, at certain historical moments, such “anomalous” phenomena may acquire particular significance, to the extent that serious doubts begin to arise about the dominant theories. These are the phases where a field enters an epistemological crisis. The result of this crisis is the emergence of a new dominant theory or a new paradigm.

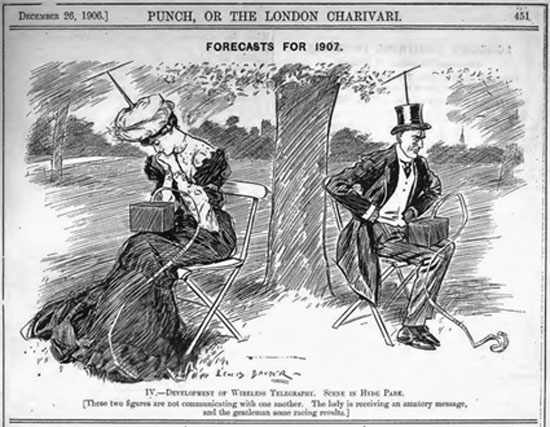

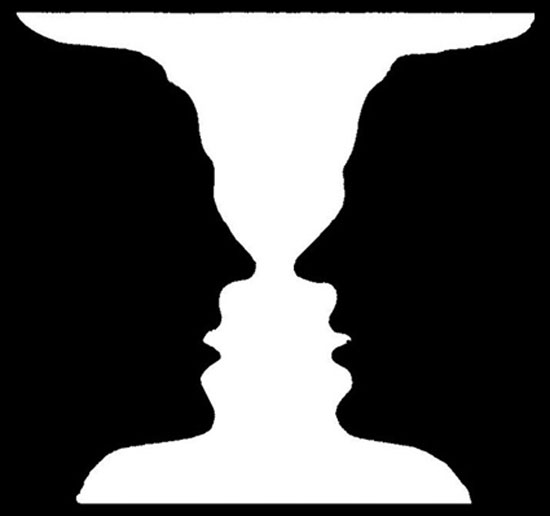

Kuhn uses the term new “paradigm,” not new “theory,” to point out the following important thing. The new theory is not simply the old theory, improved. The new paradigm is also a new way of thinking that, in many points of it, contradicts what until then was dominant. There is an incompatibility / asymmetry (the original term in English is incommensurability) that may even concern basic concepts (e.g., the concept of space in classical physics and in relativity). The “armies” of the two paradigms cannot even communicate with each other; as if they inhabit two different semantic universes. To emphasize this point, Kuhn also employs the well-known ambiguous designs from Gestalt psychology, such as the example below:

The two camps are as if they see the same image (they observe the same phenomena), but they interpret it completely differently. Some see a vase, others see two faces. It is not possible for a scientist to adopt both shapes – interpretations – simultaneously.

Before we leave the realm of epistemology, one final observation needs to be made, this time of a translational nature. The term “paradigm shift” is a Greek translation of the original term “paradigm shift.” This rendering into Greek is an unfortunate choice that, unfortunately, has now become established. It is unfortunate in regard to both words. First, the word “change” in Greek carries a connotation of neutrality, if not mildness; semantically, it is closer to the English “change.” In contrast, the word “shift” readily evokes terms such as “shape-shifting” (transformation, metamorphosis) or even “tectonic shift” (movement of tectonic plates); processes, that is, that involve an element of universality, unexpectedness, or even “force.” Secondly, the Greek “παράδειγμα” (paradigm) is equivalent to the English “example,” indicating a specific case or instantiation of a more general rule. However, the English “paradigm,” although of Greek origin and etymologically related to “παράδειγμα,” has a considerably different meaning. In fact, a meaning almost opposite to that of “example,” since it refers to a general framework; perhaps not a single rule, but certainly a set of interconnected rules that function more or less bindingly for those who adopt it. In other words, it is closer to what in Greek could be rendered as “model,” “pattern,” or even “framework.” Nevertheless, for reasons of continuity and consistency, we will also stick to “αλλαγή παραδείγματος” (paradigm change) – but essentially meaning “transformation of framework.”

about capitalist paradigm

Based on the above, the application of the term “paradigm” to the study of capitalism, to give the term “capitalist paradigm”, could mean, in its simplest form, the study of capitalist models and more specifically the study of dominant models of capitalist production. The main objection that arises naturally at this point concerns the potential misuse of terminology. The adoption of an ambiguous, and indeed unsuccessful in Greek, term instead of a simpler one (“model”) might seem like a theoretical quest and an exercise in vanity. Instead of providing sharper tools for the anatomy of capitalism, does it ultimately blunt the scalpel of criticism, leaving it exposed to the theoretical rust of generalized confusion? We believe not. It is clear that the term “paradigm” cannot be transferred as is from the field of epistemology to capitalist affairs (and future endeavors). Indeed, there are problems in its use; and we will see some of them in what follows. However, it also offers certain advantages that are not immediately obvious when more neutral concepts are used.

One of these advantages has to do with the concept of asymmetry between models that succeed one another. Each capitalist paradigm requires subordination to certain rules for its smooth operation – with whatever “smoothness” might mean when speaking about capitalism. Put in more classical terms, it is based on a given set of productive relations that allow for the reproduction and expansion of capital. However, these capitalist paradigms, initially viewed as isolated historical snapshots, exhibit fundamental asymmetries among them, despite the fact that, at a different level of analysis, they continue to adhere to the same capitalist logic.

An example (with the usual meaning of the concept…) might help here:

– The early, heroic era of capitalism had at its center the so-called “piecework production”. This essentially translated into the following property relations: The capitalist bought and had in his possession only the raw materials (and only those) that were necessary for the production of a product. On the other hand, the workers possessed both the tools and the knowledge (the means of production) required to produce the particular product. For the product to finally be produced, the raw materials were delivered to the workers, who worked with their own tools and usually in their own space (even in their own homes), to then deliver the final product back to the “entrepreneur”, who would pay them accordingly based on the quantity they delivered.

– In a later phase (industrial revolution), a spatial shift in production is observed, from the workers’ familiar spaces to that of the factory. Except that this shift was not merely spatial, but was simultaneously accompanied by a transformation of productive relations. The factory now, along with the tools and the first machines, belonged entirely to the individual owner – entrepreneur. At the same time, the factory’s logic henceforth imposed both a division of labor, to an extent unknown until then, as well as payment – wages based on working hours.

– But even the factory itself underwent internal changes, with the most fundamental being considered the transition towards the logic of the production line (early 20th century). The extensive mechanization of production through the interlinking of machines into a chain relegated the worker to a position almost external to the production process itself and the knowledge of the machines’ internals. We have now entered the Modern Times of Charlie Chaplin.

There are rather obvious incompatibilities between the three snapshots mentioned above. It is not feasible for a worker to work on an assembly line with tools that require high skill. Equally important, if not more so, is the fact that this incompatibility is not dictated solely by physical and technical constraints—although these are precisely invoked to enforce such constraints. There is a unified logic of production, a paradigm (in the sense of a model now) that imposes this incompatibility. Mass production, aiming for high productivity and presupposing a high degree of interconnection among individual productive stages, cannot afford to employ workers—skilled craftsmen who would work at their own pace and by their own criteria. And even if some such artisans remain at certain stages, the dominant paradigm demands a mass deskilling.

The concept of universality is a second advantage offered by the term “capitalist model.” However, this time, universality does not only concern production itself and its internal processes, but also the cycles that surround it: the cycles of consumption and reproduction. Any fundamental transformations in the cycle of production cannot occur in a vacuum. In their course, they drag along existing consumer and reproductive relationships—or, to avoid being accused of productive reductionism, they align with tectonic shifts in these cycles as well. Mass production cannot be conceived without mass consumption, which in turn necessitates a new round of reshaping habits and behaviors. Indicatively only: obviously, a new, higher level of wages is required, which, however, to translate into consumption, presupposes the rejection of the previous ascetic work ethic and the existence of a mechanism for creating desires. Similar transformations (in terms of their depth and scope) are identified even in the cycle of reproduction. If the capitalist model of the factory of mass production required a “reserve” of women outside of production to sustain the predominantly male working class, as well as systems of mass welfare, the current bio-informational model shifts toward logics of self-maintenance, and over time, toward logics of self-exploitation and continuous upgrading of the body–self, understood as individual capital.

about paradigm shift (and dialectic)

As we have already mentioned, the transfer of the term “paradigm shift” from epistemology to the study of a political-economic system, in order to be effective, cannot be done uncritically, especially since its use can be problematic even if one remains strictly within the realm of the history of science. According to our reading, the most significant problematic point does not lie so much in the term “paradigm” as in the second word: change. Although Kuhn convincingly deconstructed the conventional historiography of science, what he did not provide was an alternative interpretive framework that explains why and how paradigm changes occur 4. The way he describes paradigm changes gives the impression that they occur like a bolt from the blue, like radical ruptures that intervene between long periods of “normal” scientific activity. If this is combined with a misuse of the concepts of universality and asymmetry – if Gestalt patterns are taken at face value – then it easily creates the image of epistemological paradigms that are disconnected from one another, with no channels of communication. In other words, a significant lack of historical awareness emerges, along with an inability (or unwillingness) to identify those catalytic forces that initiate paradigm changes 5.

At this point, certain classical (but forgotten?) concepts from the Hegelian and Marxist tradition prove to be extremely useful tools for filling such interpretive gaps. One of the most emblematic is, of course, that of dialectics. Within the framework of this article, it is naturally impossible to provide an exhaustive presentation of such a concept, for which oceans of ink have been spent. Without ambitions of originality, we will limit ourselves to a rough and necessarily almost schematic description, focusing more on its genealogy; that is, on a historical dialectical presentation of dialectics itself. As a term, dialectics has a long history, with its origins traced back to ancient Greek thought. However, with its modern meaning, its historical line can be codified in the names of three thinkers who now hold a privileged position (rightfully or wrongfully, that is another discussion…) in the “pantheon” of philosophers: Kant, Hegel, and Marx.

When Kant entered the philosophical scene, one of the burning issues that preoccupied the minds of his time was the so-called epistemological problem – which, to a large extent, also constitutes the basic problem of modern philosophy. The problem concerns the way in which a human subject can acquire knowledge about the external world that surrounds it and to what extent this knowledge can have certainty and not be merely a chimera. In his grand synthesis, Kant attempted to contrast the two dominant philosophical currents up to that point, that of rationalism (Descartes, Spinoza, Leibniz) and that of empiricism (Hobbes, Locke, Hume), to demonstrate their limitations, and to point to a middle path.

According to the Kantian architectonic, within every human subject there exist certain inherent categories (and intuitions) through which the world is perceived and understood: for instance, the intuitions of space and time, and the category of causality. Evident is the Enlightenment note underlying this conception, since these categories constitute something like the “essence” of man, regardless of historical period or cultural context. Armed with these categories, the human spirit inevitably poses certain questions about the world and man’s place in it, and endeavors to answer them. Kant’s “innovation” here—largely due to skeptical influences—was also the realization that certain questions, although inevitable (and legitimate) to ask, cannot be answered solely on the basis of epistemological criteria. A typical example is the ancient question of God’s existence and, more specifically, the possibility of constructing a proof for God’s existence. Kant demonstrates the fruitlessness of such endeavors by employing the schema of thesis and antithesis: starting from the categories and using strict syllogisms, one can prove the thesis, that is, affirmatively answer the question about God; however, exactly the same holds true for the antithesis, since the negative answer is also strictly demonstrable. Since this contradiction does not arise as a result of any logical fallacy, the Kantian conclusion is that such a question is unanswerable, and the problem lies in the dialectical use of logic; Kantian dialectic is the logic of contradictions that emerges when the human spirit attempts to grapple with questions that transcend it 6. Therefore, for Kant, dialectic is like a quicksand of the mind which must be avoided so that reason remains within its limits and capabilities.

However, it was Kant’s successors, preeminently Hegel, who ultimately gave dialectic the meaning attributed to it today. In a movement of revolt against Kant’s “resignation” stance, with its strict epistemological limitations, they essentially rehabilitated dialectic, recognizing it as the fundamental driving force of the human spirit. Speaking in strict philosophical terms, the issue for Hegel was the investigation of the relations between the universal and the particular, through negation/abstraction. At the heart of this investigation, the goal was to reveal the unity of subject (human) and object (world); but not in a static, formalistic way, but rather as the end result of an evolutionary process that dialectically uses the tensions between these two poles as a catalyst to overcome deadlocks.

The introduction of history into the realm of philosophy marked a real turning point. Even up to Kant, as has already been mentioned, philosophy had existed as an exercise on concepts outside of time. For Hegel, however, the human spirit, even when philosophizing, is subject to the forces of history. The emergence of contradictions within the historical development of philosophy may be inevitable; yet, in contrast to Kant, such contradictions do not signify an end nor are they meant to lead to a search for refuge outside of philosophy. If negation is considered productive, then it provides an exit from the vicious cycle that begins from the position to pass into the opposition and from there back again to the position, showing a path toward the resolution of contradiction 7.

A somewhat simplistic example of using dialectics in this way could be given by examining the question of God’s existence 8. In the historical era of Christianity, the answer to this question would be something like: there exists a supreme being who created the world out of love for humanity. Entering into modernity, with the (initially timid) emergence of atheism, the denial of this position could simply be produced by adding a “not”: there does not exist a supreme being who created the world out of love for humanity. And thus two apparently incompatible answers are created. However, the denial can proceed further, ultimately producing a Spinozist position: there exists a supreme being, but it does not have anthropomorphic characteristics, such as will and mind, but rather is essentially identified with nature itself. It is evident from the above that philosophy and the history of philosophy are impossible to separate. For the human spirit to philosophize, it must also have historical consciousness.

The next step that “had to” be taken was the famous inversion of Hegel, so that he would stand with his feet down and his head up. Although, strictly speaking, Hegelian philosophy (and the entire German idealism) was not ontologically dualistic, it nevertheless gave a priority, as it were genetic, to what we call “spirit”. Marx adopted dialectics, applying it at a more grounded level; in understanding human history in its material, practical and active aspect. It is not only spirit that evolves dialectically, but also human activity, human action within the material world. Something that can be observed even more specifically in the evolution of capitalism. Each dominant capitalist model (or paradigm) contains contradictions – anomalies which, in their development, can reach a point of explosion. In their most general form, these are the contradictions between productive forces and productive relations, which a capitalist system can dialectically overcome, evolving towards a new model, carrying within it elements of the old, even in their negative form. The fundamental contradiction, however, is that between the social production of wealth and its individual appropriation through private ownership of the means of production. Since this contradiction lies at the heart of capitalist production, any possible transcendence of it cannot simply lead to a new capitalist model, but ultimately to communism.

about changing the capitalist paradigm

If the contradiction between the social production of wealth and its individual appropriation, as Marx identified it, was universally accepted by all subsequent Marxist currents, orthodox and non-orthodox alike, there is another fundamental element of capitalism that generates tensions within the productive process, but which was ignored by orthodox Marxism: the intensive use of machines. Although Marx himself had made certain insightful observations regarding the use of machines,9 this issue was treated with proverbial simplification by his orthodox successors. Technological development (the development of productive forces) was regarded as an inherently progressive and desirable process, to such an extent that capitalist relations of production came under criticism because (it is assumed) they posed barriers to further development, with the logic that only a different social model could unleash the productive forces, and thus both science and technology.

The rethinking of the relationship between development and capitalism is largely owed to Italian autonomism and the theoretical work undertaken during the turbulent decades of the 1960s and 1970s.10 Starting from the exactly opposite position—that capitalism and development not only do not oppose each other, but are organically linked—they attempted to demonstrate how capitalist production “progresses” toward higher levels of development. And here, the concept of dialectical development through negation, and specifically through the negation of workers as subjects,11 was honored.

The introduction of new technologies in production does not occur due to an abstract, supposedly inherent, human predisposition for more efficient exploitation of nature (to overcome the scarcity of goods). On the contrary, it is precisely the workers’ refusal to submit to the prevailing productive norms that catalytically drives the search for technological innovations. Capital, in an attempt to nullify such refusals, engages in a struggle to extract greater relative surplus value through restructuring the productive process. It tries to find a new productive model (paradigm) by deconstructing and reconstructing labor, transferring aspects of living (human) labor into the dead; in other words, by introducing newer, more “improved” machines. It deepens the degree of alienation of labor by incorporating into machines knowledge previously held by workers (increasing its organic composition), thus rendering them interchangeable and minimizing the risk of their refusals.

The outcome of this struggle between labor and capital is, of course, not predetermined. Yet even if capital manages to impose its will, class conflict does not disappear but shifts to a “higher,” more socialized level. A simple example: large-scale industry, by fragmenting labor, renders it meaningless from the workers’ perspective; however, in doing so, it feeds working-class discontent (to put it mildly). The entire industry of exploiting free time, from entertainment to all kinds of hobbies, is now called upon to function as a valve for releasing such tensions. And thus, the conflict comes to encompass even spheres outside production, such as consumption. In the words of Tronti 12:

“When capital conquers all spaces that lie outside capitalist production proper, it initiates a process of internal colonization; indeed, only when the cycle of civil society – production, distribution, exchange, consumption – is completed, can one begin to speak of capitalist development proper… At the highest level of capitalist development, the social relation becomes a moment of the production relation, the entire society becomes an articulation of production; in other words, the entire society exists as a function of the factory, and the factory extends its exclusive sovereignty over the whole of society.”

A new capitalist paradigm therefore is in no case detached, as if it were the result of a flawless conception. It carries within it a history of denials, a history of workers’ denials; and the reluctance to acknowledge these denials, especially by those who would normally have an interest in recognizing them, produces a theoretical stance that resembles the ridiculous figure of a petty bourgeois, with upward ambitions, who insists on denying his “humble” roots, thinking that this way he will fit into an environment that has spit him out from the outset.

Separatrix

cyborg #11 – 2/2018