What is a “smart city”? 1 The sum of various “smart” devices and applications? Or the technological shaping of a large-scale unified and controllable “shell” for social relations, which composes technology with power, counting/recording with control, and capitalist profitability with yet another restructuring of the “human,” to an extent and intensity unprecedented in history? Is it simply another expression of technological futurism? Or is it something that happens this way, in ways that escape us?

Already from the first issue of Cyborg (October 2014), Rorre Margorp made a first presentation of the topic 2. We return with the first part of a text 3 published on the website of the electronic magazine “first monday”, on July 6, 2015, titled The spectrum of control: a social theory of the smart city.

The interest does not lie in the short-sighted expectation that “tomorrow” the designs of computer companies will be completed reality. But in the strong tendency for a general reconstruction of the social, which constitutes the banner (not always distinct…) of the “4th industrial revolution”.

introduction

The idea that cities allow everyone to feel at home everywhere, and at the same time to be a stranger, holds a certain appeal. You can know the streets, the shops, the boulevards and the alleyways, and at the same time move about in them for days without being met by anyone who knows you. But as governments and corporations, often in close collaboration with each other, fill cities with “smart” technologies (turning them into platforms for the internet of things: sensors and algorithms embedded in all kinds of objects that connect, communicate or/and transmit information between themselves or via the internet), they increasingly narrow the margins for escaping this omnipresent web of surveillance. Soon, for example, shoppers or those who window-shop will be as familiar to retailers as these places will be familiar to them. Facial recognition software and data emissions from smartphones will constantly reveal everyone’s identity, consumer habits or tastes.

Big data is the new commercial currency. However, as is generally the case with money, some have much better access terms to it than others. It is already happening elsewhere: when a loan is made, for example, the borrower is required to provide detailed personal information to close the deal; the bank, on the other hand, has no obligation whatsoever to explain in writing, with the same level of detail, its internal processes in making its decisions. The same asymmetry appears in the formation of the internet of things: powerful organizations acquire more and more user data but deny similar access either to users or to regulatory authorities to their own secrets, even when abuses and violations of rights become known. It no longer makes sense to think of the internet as something to which everyone has access via a computer. Cities themselves are being redefined and reshaped as platforms for and as nodes within networked information/communication technologies.

One of the central articles of the wired magazine on the subject of the internet of things makes the rhetorical question: “Have you ever lost something in your house and wished you could easily find it with a simple “keyword” search, just like when you search for a file on your hard drive?” You can make it a reality now, thanks to a startup company, named StickFind Technologies, which sells small, cheap, adhesive sensors that can be placed anywhere. Lost your child in the mall? The “smart fashion” RFID tags can keep it constantly connected to the network, and therefore constantly traceable.

And why stop only at locating your children once you get familiar with the sensors? Soon your body, your home, your devices and everything else in your environment will be the source of a continuous stream of networked communication. On an urban scale, the city will become a cocoon of connectivity that will envelop us (or a web that will trap us) as “smart technologies” become increasingly integrated into our daily lives. These technologies are presented as techniques of locating and navigating. They are search technologies (when we use them) and evaluation technologies (when used by others, with us as material). They map, classify, evaluate: and what, indeed, could be more harmless than simple information?

Weighing the pros and cons that such innovations bring is a Sisyphean and entirely ideological task. Who can know what ominous or impressive applications may emerge? However, analyzing the possibilities could offer an alternative approach compared to forecasting a balance of benefits versus harms. Such an approach takes into account that the harm caused by the loss of privacy, as proclaimed through the expansion of the Internet of Things, is not compensated by the benefit of convenience in using various applications.

Nevertheless, governmental and corporate rhetoric about the Internet of Things marginalizes the most important analyses of negative consequences, dismissing them as paranoid. Technocrats distort political assessments regarding pervasive and generalized surveillance and control within urban environments. Moreover, the criteria they provide to evaluation agencies, which focus on users’ “consent” to surveillance, are flexible enough to legitimize even the most intrusive monitoring applications—for instance, the use of drones to manage crowds of protesters or car rental technologies that immobilize a vehicle if there is a slight delay in rental payment—presenting them as expressions of democratic will and market rationalization.

what is a smart city;

On a global scale, the development of “smart” cities is advancing rapidly. A 2013 report prepared by the UK Department for Business and Innovation estimated that “the global market for smart city applications and related services will be around $408 billion by 2020.” This growth has been accompanied by the exponential expansion of the Internet of Things. According to figures widely available from the telecommunications giant Cisco, one of the key companies involved in the Internet of Things and smart cities, billions of objects are already interconnected, with “over 12.5 billion devices connected in 2010 alone.” They predict that “approximately 25 billion devices will be interconnected by 2015, and 50 billion by 2020”4. Less conservative estimates place the smart cities market in the trillions of dollars over the next 5 to 10 years, with the Internet of Things market expected to be even larger. IBM recently announced that it will invest $3 billion over the next five years to create a new Internet of Things unit, an investment that will certainly boost IBM’s existing “Smarter Planet” business initiative.

Whether from the perspective of assessing the market that is being shaped, or from the perspective of the capital that needs to be invested, or from the perspective of technological development and the impact of the transformations taking place, the “smart city” is an enormously challenging endeavor. Emerging as a current of urban planning and rationalization of governance, the promotion of “intelligence” (of cities) is primarily carried out by large corporations that strive (and succeed) to make the various city authorities their advocates. This is not about discovering a virgin market whose needs must be identified. But rather about inventing an entirely new one; hence, shaping it.

However, despite this large-scale capital investment, the definition of “smart city” remains nebulous. There is no fixed content implied each time these words are used. The ambiguity suits the promoters of the urban intelligence idea perfectly. The words “smart city” hang in the air and shift direction according to interests. This flexibility – within – ambiguity allows for the creation of a fluid yet dynamic promotion of products, state actions, and policies. Providing them with coverage in case they need to be reversed if something ultimately goes wrong or fails to meet some promise.

The typical examples used propagandistically to depict and accept a world that will be the internet of things are various consumer products – such as the brand new “smart fridge” that notifies the supermarket when you run out of milk. But Bruce Sterling argues that this is a fairy tale. And that the genuine internet of things wants to break into the fridge to count, organize and monitor every movement as soon as its door opens; and that it would gladly sell such a fridge at cost price, in order to profit from controlling its usage.

Focusing on consumer devices is misleading and keeps attention on superficial issues, trying to limit the analysis of developments to the emotional sphere. The major business alliances currently being formed aren’t about selling consumers “smart fridges”! They want to advertise living in “smart cities,” where the term “intelligence” is defined by corporations that disregard individual consent point by point. The “smart city” is not simply a linear scaling up of the “smart home” concept, in which all personal and household devices are interconnected and automated. It is, primarily, about appropriately shaping infrastructures and urban applications in such a way as to favor a new techno-political configuration of society, through data concentration and processing and corresponding applications.

Not every “smart city” is developed in the same way. We can distinguish three basic approaches:

First, the most common existing “smart cities” are those that have been retrofitted with technology, upgraded from “dumb” to “smarter.” Various estimates place the number of cities in this category at several tens or even hundreds of thousands worldwide. In these cases, “the smart city is assembled in fragments, upgraded haphazardly through existing institutions of governance and built environment. Typically, the motives stem from political economy, resulting from the increasingly intense entrepreneurial form taken by municipal authorities aiming to make one or another city a center (regional or global) of competitive economic development. Making a city ‘smart’ here is the ultimate means of imposing austerity policies, managing the city, and transforming it into an attractive destination for capital flows; all this through the utilization of ‘network infrastructures to improve economic and political efficiency, and activating the social and cultural environment.’ In this sense, ‘smart’ initiatives promise to provide municipal authorities with the tools to achieve their entrepreneurial goals.

Second, there is the method of “shock therapy” (we could call it “smart shock”), where a city undergoes a rapid and large-scale integration of “smart” standards, technologies, and policies into an existing urban environment. There is not yet any city that has experienced a complete shock of this kind; rather, there are examples where the transition to the “smart city” occurred to a greater degree and at a much faster pace than in typical cases. Perhaps the best example is the Operations Center that IBM created in Rio de Janeiro in 2010. According to its creators, “the center aggregates data streams from 30 organizations, including transportation and public transit, municipal services, emergency services, weather forecasts, and information sent by workers and the public via phones, internet, and radio stations, into a single data analysis center.” With this NASA-style control center, the city of Rio became a system of optimization and control. Different aspects of urban life can be thoroughly monitored and precisely managed, reinforcing already existing forms of military-style urban control. IBM and other technology companies have created similar data centers in other cities, usually for the use of individual services (police departments), but none of these have reached the scale of Rio’s Operations Center. Therefore, there are several indications that Rio is a projection of the future, for the kind of systems expected to be rapidly created and developed in other cities.

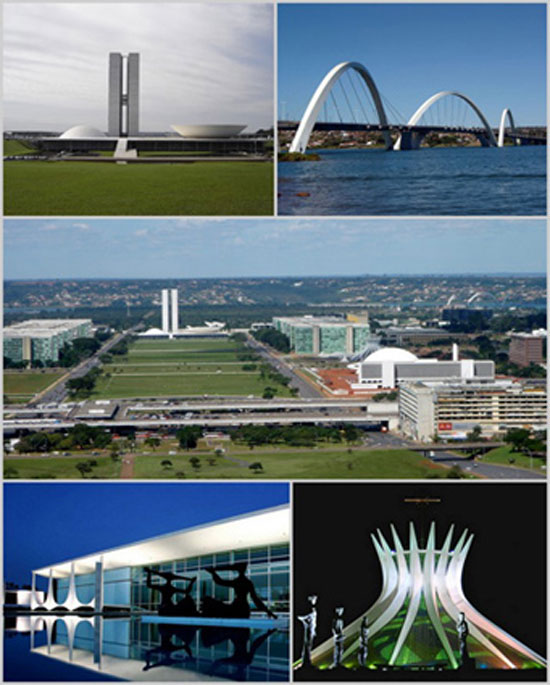

Third, the ideal models of “smart cities” are plans created from scratch, built in places where there was no prior urban concentration. A paradigmatic case is New Songdo in South Korea, which currently serves as a kind of global “anatomy table,” an urban laboratory for the large-scale application of smart systems from the ground up. With a cost of nearly 40 billion dollars, the business and governmental supporters of Songdo hope to create the world’s first fully “smart city.” As Christine Rosen (2012) observes, “Songdo presents intelligence that does not arise from its residents, but from the millions of wireless sensors and microcomputers embedded in surfaces and objects throughout the metropolis.” This “Songdo type” is a window into a vast, yet still potential, urban future. Moreover, the “Songdo type” shows striking historical similarities between the ideology of the “smart city” and the ideology of 20th-century architectural modernism. It should be noted that Brazil’s federal capital, Brasília—a monument to modernist ideologies of technocratic governance—was built in only 41 months (from 1956 to 1960), on cleared land from the Amazon rainforest. “Point by point,” writes Adam Greenfield, “whether out of ignorance, historical amnesia, carelessness, or hubris, the designers of Songdo, Masdar5 and PlanITValley6 [other cases of prototype smart cities] recapitalize the hyper-specialization, hubristic scientism, and rigid authoritarian megalomania of Chandigarh and Brasília, from beginning to end.”

Even with this pluralism of methods and incentives, we believe it is possible and necessary to begin analyzing the underlying sociopolitical logics that are common to all initiatives and versions of “smart cities.” The trend toward these does not seem to be slowing down. The ideas and practices of this trend continue to colonize the urban landscape and the political imagination of local leaders.

Given the limitations of this text, our overview aims simply to lay the groundwork for a social critical theory of the phenomenon. For a more thorough genealogical analysis of the dominant discussions and ideologies shaping these sociotechnical systems and corresponding policies—particularly those originating from large corporations such as IBM, Cisco, and Siemens—we recommend readers consult Adam Greenfield’s comprehensive brochure “Against the Smart City.” 7

Furthermore, we must be clear: the generalized use of the term “smart city” hereafter serves as a kind of coded reference to the technologies and techniques aligned both with the practices and ideologies of the “smart city,” regardless of their scale or type of application. We neither homogenize nor equate the various interpretations of the “smart city” offered by different municipal authorities, politicians, or companies. On the contrary, we seek to draw attention to the ways in which seemingly different technologies and techniques share a common origin and reproduce unified sociopolitical choices.

The next section presents the ideologies—updating and adding depth to Greenfield’s study—that are incorporated and implemented by “smart city” initiatives.

Aerial views of Brasilia.

the ideology for the smart city

In the most official version of defending the choices that support the development of smart cities, the linear perception of technological progress offers a supreme fantasy: the Internet of Things. In an article in Foreign Affairs magazine that has become a reference text, two of Cisco’s executive directors declared the benefits of applying i.o.t. to almost every aspect of urban infrastructure and city governance. And what did they not promise? “Smart and efficient management of urban development,” which would reduce “traffic, congestion due to insufficient parking, pollution, energy consumption, and crime.”

Who could be opposed to all this? The only cost, the CEOs assured, would be a small reorientation in governance and technology procurement strategies. Because first, “the world must rethink the purpose of investments in information technologies” by “moving away from purchasing individual services and instead focusing on integrated solutions that are incorporated into systems at various levels.” And because, secondly, “hyper-collaborative public-private partnerships,” with strict “adherence to deadlines,” are essential. As one of their principles for creating smart cities, the “global” rule they promote declares that “the world should not be afraid to adopt technology in new ways. This entails re-examining the contracts with citizens regarding the services provided to them by information companies and governments.”

The shift in political terminology—from the social contract to the corporate contract—is subtle but crucial for understanding the politics surreptitiously introduced into the technocratic agenda of “smart cities.” This explains why the six principles proposed by advocates of “smart cities” are all directed against “municipal authorities” that do not (sufficiently) utilize the products and services offered by the information technology sector for cities.

As entrepreneurs conscious of their interests, the drafters of these principles acknowledge the asymmetry of relations between the public and private sectors in an era of neoliberalism. However, when the earnings of top corporate executives are multiples of those of top public officials, the latter are willing to directly allow businesses to reshape the public, “in their own image and likeness.” Companies can afford to hire large numbers of economists, designers, lawyers, and public relations specialists to help present the future of cities as technologically deterministic—where there is no alternative except their own proposals. Indeed, apart from the corporate model, “there are no large-scale alternative models for ‘smart cities,’ partly because most have already adopted business-oriented models of urban development.”

Undoubtedly, Cisco has commercial interests here: the design, construction, and installation of this hardware is vital for Cisco, and its future profitability depends on the company’s ability to craft compelling narratives of “intelligence.” However, many public officials and non-profit organizations have also jumped on the bandwagon. One can also find material incentives here, as research demonstrates the interconnected employment and career vessels among companies, the public sector, and the “third sector.” When public employees can earn significantly more by jumping from government agencies to corporations if they are flexible and collaborative, few have the incentive to ask difficult questions at the expense of businesses. The boundaries between the public and private sectors are porous.

Beyond material incentives and career ambitions, and equally important with them, the rhetoric of the “smart city” rationalizes urban transformations appearing as a representation of technological systems and their capabilities. In a comment, in a study on “smart cities”, geographer Rob Kitchin supports that the way in which “most of the written and oral discourse related to ‘smart cities’ either comes from companies, or from academics or governments, ‘seeks to appear ideologically neutral, common-sense and realistic'”. It is a burst of technocratic neoliberal ideology, but also of a broader political-economic imaginary about steady profitability and taxation. Supporters of the “smart city” pose as hard-core problem solvers, bypassing zero-sum politics which often cause conflicts.

However, very often they fall into the condition ironically described by Clifford Geertz as follows: “I have a social philosophy; you have a political opinion; he has an ideology.” This trichotomy is convenient. The “I” could be the contractors of “smart cities”; the “you” the municipal authorities; and the “he” the various population groups showing deeper concerns regarding mass surveillance and control applications and data processing.

Take, for example, a speech by Samuel Palmisano (in 2010), then president and CEO of IBM, where he argued that “building a smarter planet is realistic precisely because it is so refreshingly non-ideological.” However, as Geertz explains, the use of the term ideology with the aim of isolating “them” is one of the most ideological practices of contemporary rhetoric about “smart cities,” a way of concealing the most questionable values and assumptions that drive its proponents.

For a better understanding of the political character of the “smart city,” one can think of a logical extension of an already existing “smart city,” as proposed as a thought experiment by the philosopher and legal theorist Lawrence Solum. Singapore has “smart intersections that adjust traffic lights according to traffic flow.” And one can imagine even more complex methods of controlling vehicle flow.

Solum takes it further, proposing the development of an “Artificially Intelligent Traffic Authority” (AITA), which could “adapt to changes in driver behavior and traffic flow.” This system should be designed to “introduce random variations and run controlled experiments to evaluate the impacts of various factor combinations on traffic conditions,” recalling Jim Manzi’s recommendations for much more experimentation in public policy.

But this system would not be particularly lenient toward individual experiments, say, violations of its rules. On the contrary, as Solum envisioned it, “violations would be detected by a complex electronic surveillance system” and offenders “would be identified and immediately removed from traffic via a crane system located at key intersections.”

Solum used this example not as a proposal for the future organization of traffic, but to highlight the overcoming of the usual differences between human and technical conceptions of the law. His scenario is useful to indicate the inevitable legal and political aspects of automated, mechanically mediated enforcement of the law, even in an apparently technical issue, such as urban traffic. In Solum’s hypothetical scenario, then, could cranes “surgically” remove protesters, like those in Ferguson who were blocking highways? Could they remove anyone with an expired driver’s license or vehicle safety certification?

The goal of smart city advocates is to apply the corporate governance model first to the identification, then to the prioritization, and finally to the resolution of urban tensions; that is, life in cities. This means the appropriate selection and promotion of “problems to be solved,” in a comprehensive manner.

Let’s take a few easy and obvious examples: should new forms of surveillance first focus on combating drug trafficking, on indicators of economic crimes, or on employers’ unfair labor practices? Wage theft is a huge problem, but it is rarely taken seriously by authorities. Cameras and sensors in restaurants focus on preventing food theft by employees, on preventing food poisoning, or on detecting violations of safety measures? Does “traffic control” also include efforts to stop horns from honking late at night, or is dealing with this noise considered expensive in “smart” ways, and anyway “self-regulated” through millions of small police acts every year, in contrast to the problem of “pedestrian traffic obstruction” which is usually used by police as justification for harassing African Americans standing on sidewalks? Would autonomous car control systems preferably prevent pedestrian deaths, or would they simply seek to ensure smooth flow of cars to and from the city?

The ideology of neoliberalism very often provides quick, “obvious” and undisputed answers to questions that are formulated as variations of cost-benefit relationships. It is understood that it is business ethics that can manage these relationships in a better way; and “they” abound. The “you” remain, the public organizations, who should realize the dynamics and effectiveness of business planning.

The matter is evolving with enthusiastic simplicity! In February 2015, the Senate of the United States organized a hearing with the theme “the connected world: examining the internet of things.” The statement of Democratic senator Cory Booker was representative:

This is an amazing opportunity for a bipartisan, deeply patriotic approach, on an issue that could ignite our economy. I think there are trillions of dollars, to create countless jobs, improve quality of life and democratize our society in ways that offer advantages to people who are marginalized, removing the barriers of race and class.

We can’t even imagine the future that is promised and we should embrace it… And so many of my concerns are those that are also repeated by my Republican colleagues, that is, we must do everything possible to encourage it, and nothing to restrict it…

Doing anything to prevent this leap of humanity, seems unfortunate to me… And I also believe that this must be done through a public and private sector collaboration. We all have a role to play.

Booker’s statements are the commonplace views about innovation and technological progress in society: the best thing we can do is to get out of the way. At best, our duty is to provide all the legal, material and ideological support we can for innovations – and innovators – such as the internet of things.

Whoever wants to ask difficult questions about the future, let alone restrict and slow down technological development, de facto destroys a growing economy and stands in the way of a democratized force for justice. This is not patriotic…

Related is the projection of technological “housewifery” in urban budgets: more with less. It is as if the neoliberal idea of effectiveness is electronically equipped to the point of constructing a total environment, digital and physical. For example, the time spent on organizing and developing a “platform where citizens will engage with the municipality but also with each other through text, voice, social media, and other applications” is not time spent on highlighting the consequences of tax evasion by the wealthy. Would the city of Newark or New Jersey have needed a “donation” of 100 million dollars from Mark Zuckerberg to improve their educational system, if all billionaires had managed perfectly well to reduce their personal and corporate taxes and to relocate their wealth to safe foreign places?

Every time a “quanttrepreneur” proposes new smart ways of measuring and maximizing the “efficiency” of public employees, some with critical thinking should ask: Where does the pressure to “do more with less” come from? The focus on technology through which “more is done,” on technology that responds to issues convenient for companies, displaces the crucial discussion on the causes of “fewer” governmental resources and workers.

…

translation:

Wintermute

Ziggy Stardust

- We use the words “smart city” in quotation marks to emphasize the fact that the language used has already become a vehicle of rhetoric, with all that this entails. Because who wants to be “stupid”? Therefore, even words secure a priori an advantage for some. ↩︎

- Cyborg #01, Smart cities ↩︎

- For the authors: Jathan Sadowski is a professor at the University of Sydney, specializing in “smart cities”. Frank Pasquale is a law professor at the University of Maryland, specializing in the legal dimensions of big data… ↩︎

- https://archive.is/vdpCr ↩︎

- Masdar city is an urban project under construction in the United Arab Emirates, funded mainly by the local sheikhs. Construction began in 2008, but due to the global economic crisis its development has been considerably delayed. According to the initial design, Masdar (which is promoted as the city with “absolutely clean energy production”) will have between 45,000 and 50,000 residents, and 1,500 businesses. Around 60,000 workers will commute to it every day, but they will not live there… ↩︎

- PlanITValley was a project to build a “smart city” from scratch in Portugal, near Porto. Construction never began due to various problems, mainly disagreements between the key “visionaries” and partners, after their initial enthusiasm. ↩︎

- Against the smart city, ed. 2013. Although critical of these projects, Adam Greenfield belongs to the “born-again” of the relevant global industry. From 2008 (at 40 then) until 2010 he was design director, in the interfaces and devices department of the Finnish Nokia. In 2010 he returned to New York and created a design system for communication/digital systems on a city scale, which he named Urbanscale, which he promoted as “ideal for designing interconnected cities and citizens.” In 2013 he won a scholarship for postgraduate studies at the London School of Economics, and since then teaches at the architecture school of University College in London. His most well-known book is titled Everyware: The Dawning Age of Ubiquitous Computing. ↩︎