“Revelation! The Luftwaffe bombs London.” Such a front-page headline in a British newspaper, during the Second World War, would have certainly been unthinkable; war then was the directly experienced reality in terms of harsh materiality. Certainly, there were developments, operations and events well hidden and unknown to the mass of the population, just as there was abundant propaganda that distorted reality. But the war itself, the fact that societies across Europe and subsequently almost the entire planet mobilized and became involved in a deadly confrontation, was not a matter of journalistic coverage in order to document that it was happening.

Today, however, front-page headlines such as “50 million Facebook profiles stolen by Cambridge Analytica in the biggest data leak ever” or “The great British Brexit heist: how our democracy was pirated” rightfully claim the characterization of “revelation,” without violating common sense and the basic understanding of what is happening in the world. This is indeed revelatory journalism. Because the majority in Western societies stubbornly refuses to acknowledge the harsh reality of the evolving fourth world war, and because generalized digital mediation continues to abundantly provide the soothing illusion of some normality, cyber warfare rages in cyberspace in an imperceptible way, like a massive escape, disguised sometimes as social media nastiness, sometimes as criminal or even coup-like practices of unscrupulous companies, and sometimes as the mischief of troll factories (preferably Russian ones), but never, but never, as what it truly is: a piece of the world war; the fifth dimension of the modern battlefield that centrally concerns the “handling of population behavior” on a large scale.

There are two versions of the same story. One begins on March 17, 2018, when simultaneous reports in the Guardian and the New York Times revealed that Cambridge Analytica had stolen 50 million Facebook user profiles, in order to boost, through psychological methods of black propaganda and brainwashing, the Leave EU campaign in the British referendum and Trump’s campaign in the American elections. This version includes the necessary international uproar over how unprotected personal data is on the internet, the classic accusations of Russian involvement, a Zuckerberg dragging himself before congressional committees and now the European Parliament in order to justify the unjustifiable, new regulations and rules for personal data protection, bankruptcy of the company-stone of the scandal… and somewhere around here the story runs out of steam.

The second scenario belongs to the thematic of war (and constitutes a continuation of another online “scandal”, that of fake news, about which we have already written: don’t believe the hype: social media and black propaganda, cyborg #8). It begins several years earlier, with protagonists being the deep state mechanisms in the US and Britain emerging from the shadows of the backstage and assuming, due to the crisis and evolving conflicts, the direct responsibilities of war management. For reasons that are not within the scope of this text to analyze, the realignment of the two closely allied capitalisms involved, on one hand, the complete detachment of Britain from the European bloc and exit from the EU, and on the other, the assumption of the American presidency from a facade behind which it would become feasible to disengage from past strategies deemed unsuccessful. If these were the immediate political objectives, there was simultaneously a second, more social, pursuit: for the far-right and racist current of petty bourgeois fascists to become not only predominant, which it already was, but also formally hegemonic, with solid and undisputed political representation across the entire spectrum of the state.

As has already been happening for years with war contracts, the work has been broken down into subcontracting and outsourced. What we know for sure is that a piece of it was given to a British company, SCL, which was directly drawn from and staffed by the British deep military establishment. The company’s credentials were impressive. Through “strategies targeting specific behaviors” (according to its website), it had a presence and operations across all open fronts of the planet, from the Middle East to Central Asia and from Africa to Eastern Europe, with extensive experience and high operational readiness in this field, which in modern military terminology is characterized as “psyops” (psychological operations) or “information operations.” In all cases, SCL—advertising itself as being “at the forefront of cyber warfare”—employed techniques developed in military laboratories, ranging from torture and interrogation methods to the dissemination of fake news, propaganda, and mass manipulation. In short, it is a company-branch of the Anglo-Saxon military establishment, which had recently added big data and its analysis to its fields of operation. And what happens when a company with such a background and such tools at its disposal gains access to a vast reservoir of personal data? The equivalent of a nuclear bomb, in digital form—or to be precise, an extensive, well-designed, and meticulously executed cyber warfare operation, the largest of its kind to date…

In Britain, the plan worked flawlessly and the choice to leave the EU was triumphantly and democratically endorsed, revealing the nadir of the British political scene with the protagonist of post-European Albion. In the US, it seems that the initial choice of mechanisms was to promote Ted Cruz, who indeed evolved from an outsider to a favorite, noting some completely unexpected victories in primary elections. However, for reasons we ignore, his momentum deflated until he eventually withdrew from the race and Trump took his place. We also do not know all the reasons why the deep American state chose such a shabby pawn for its showcase, but we certainly know that he was so naive and so narcissistic that he followed to the letter the algorithmic commands set by his digital instructors. And so, for the first time, cyberspace produced a president, a “perfectly weather-forecasting algorithm… whose every message was almost a product of data.”

psychometrics and big data: the science of manipulation

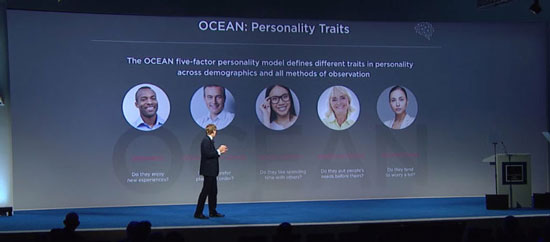

Psychometrics, or psychographics as it is sometimes referred to, focuses on measuring psychological characteristics and quantifying personality. In the 1980s, two groups of psychologists developed a model that was supposed to be able to assess and classify people based on five personality traits, known as the “Big Five.” These are: openness (how open you are to new experiences?); conscientiousness/diligence (how perfectionist are you?); extraversion (how social are you?); agreeableness (how agreeable and cooperative are you?); and neuroticism (do you get upset easily?). Based on these five dimensions (also known as OCEAN, an acronym from the five English terms: openness, conscientiousness, extroversion, agreeableness, neuroticism) psychometricians claim that they can make a relatively accurate assessment of the person sitting across from them. This includes their needs and fears and how they might behave in specific situations. The “Big Five” model became the standard technique of psychometrics. But for a long time, the problem with this approach was data collection, because it involved completing a complex, highly personal questionnaire. But then came the internet. And Facebook. And Kosinski, a Polish graduate student at Cambridge.

Michal Kosinski was a student in Warsaw when he was accepted, in 2008, to Cambridge to pursue his PhD at the Psychometrics Centre, one of the oldest institutions of its kind worldwide. Kosinski began collaborating with his fellow student David Stillwell (who is now a lecturer at Cambridge’s Judge Business School) on building a small application on Facebook; Stillwell had already been working on the application for about a year, back when Facebook was not yet the behemoth of our time. Their application, called MyPersonality, asked users to complete various psychometric questionnaires that included a plethora of psychological questions from the Big Five questionnaire (“Do you panic easily?”, “Do you oppose others?”…). Based on the assessment, users received a “personality profile” – their scores based on the Big Five model; they were also asked to give their consent so that researchers could gain access to their Facebook profile.

Kosinski expected that the response would be limited to a few dozen acquaintances from school who would complete the questionnaire, but before too long, hundreds, thousands and then millions of people began to reveal their most intimate beliefs. Suddenly, the two doctoral candidates found themselves in possession of the largest dataset ever collected that combined psychometric results and Facebook profiles.

The approach that Kosinski and his colleagues followed in the following years was, in fact, very simple. First, they gave the research subjects a questionnaire in the form of an online quiz. From the answers, the psychometricians calculated the personal Big Five values of the participants. Kosinski’s team then compared the results with all kinds of digital data of the subjects: what they “liked”, the comments they shared or posted on Facebook, or what gender, age and place of residence they declared, for example. This approach allowed the researchers to connect the dots and draw correlations.

The psychometricians concluded that particularly reliable inferences could be drawn from simple digital actions. For example, men who “liked” the cosmetics brand MAC were slightly more likely to be homosexual; one of the best indicators of heterosexuality was liking Wu-Tang Clan. Lady Gaga’s followers were probably social, while those who liked philosophy topics tended to be introverted. While each piece of such information is too weak to support reliable estimates, when dozens, hundreds, or even thousands of separate data points were combined, the resulting estimates were considered extremely accurate.

Kosinski and his team continued working on their models. In 2012, Kosinski claimed that based on an average of 68 Facebook “likes” from a user, he could deduce skin color (with 95% accuracy), sexual orientation (with 88% accuracy), and preference for the Democratic or Republican party (with 85% accuracy). But he didn’t stop there. Intelligence, religious choices, as well as smoking and alcohol and drug use, could all be determined. From the data, it was even possible to infer whether someone’s parents were divorced.

The power of the model was revealed by its reverse application: conclusions could indeed be drawn about an individual’s personality based on their data, but also, the analysis of the data could predict the individual’s responses and attitudes. Before long, Kosinski was able to assess a person better than any other researcher at the school, based on just 10 Facebook “likes.” Seventy “likes” were enough for conclusions that surpassed what the person’s friends knew; 150 surpassed what their parents knew; and 300 “likes” what their partner knew. Even more “likes” could surpass even what the person thought they knew about themselves.

But now the research had nothing to do only with “likes” or even Facebook: Kosinski and his team could now extract the Big Five values based exclusively on how many profile photos a person has on Facebook or how many contacts they have (a good indication of the degree of sociability). However, we reveal things about ourselves even when we are not online. For example, the motion sensors in our phones reveal how fast we move and how far we travel (data that researchers correlate with the degree of sociability and emotional instability). Smartphones, was the conclusion, are a huge psychological questionnaire that we continuously fill out, both consciously and unconsciously.

Above all though – and here’s the key – the thing works in reverse too: not only can the psychological profile of a person be created from the data they produce, but the data can also be used inversely by searching for specific profiles: all anxious fathers, all angry introverts, all unruly teenagers – or perhaps even all undecided voters. Essentially, what Kosinski had invented was a kind of person search engine.

The publication of the research caused a tremendous impression; it was original, unusual, and had obvious potential. For whom? Secret services and military research centers lined up to meet Kosinski, and the Psychometrics Center organized regular demonstrations for their benefit. For example, during one such demonstration for the secret services, a specific test named “you are what you like” was presented. It showed some strange patterns; for instance, people who “liked” comments such as “I hate Israel” on Facebook also tended to like Nike shoes and KitKat chocolates. This particular research had the nickname “Operation KitKats.” The result of these demonstrations was that organizations funding research on behalf of the secret services fell headlong for the work of Stillwell and Kosinski.

The defense and military establishment was the first to see the potential. Boeing, one of the largest contractors for the U.S. armed forces, funded Kosinski’s doctoral research, and DARPA, the secretive agency for advanced military projects, is cited in at least two academic papers as supporting his work. But when the first major publication about the research emerged in 2013, others also recognized the possibilities. Among them was a British company named SCL.

information operations: war in the age of universal digital

“Information Operations [in Greek, the term could be rendered as “information operations” or “cyber operations”] are the combined application of electronic warfare, cyber network operations, psychological operations (psyops), deception using military means, and security operations, aimed at exerting influence, disruption, erosion, and/or appropriation/neutralization of adversary individuals and automated decision-making processes, while simultaneously protecting our own.” This is the official definition of information operations, as included in U.S. military manuals and cited in Wikipedia.

Techniques that were systematized and developed during the Cold War, when military conflict between the two rival blocs evolved indirectly, covertly, and through intermediaries, the I.O.s were further upgraded and evolved even more in the 21st century, to the extent that electronic networks and generalized informatization added yet another field of warfare. Because they are by nature operations conducted in the shadows, and their effectiveness requires concealing the real instigators behind them, and moreover, because they rank among the most shameful practices of military methodology, it is technically difficult for the “official” military or secret services to openly organize and execute them; dirty work is best always attributed to others. Nowadays, this issue has been resolved in the same way capitalism has addressed a series of other issues: through outsourcing. Thus, companies have been established with military funding, equipped with military expertise, and staffed with former military personnel, aiming to undertake the execution of information operations within the framework of an undeclared, yet real and evolving cyber warfare. This is not simply a “privatization” of military operations, as is rampant with mercenary companies, but something more: it is a kind of distorted socialization of war. Furthermore, such companies also address an additional practical issue, that of attracting the appropriate human resources. Many nerds might object to working for the CIA or the British Royal Army, but they would hardly refuse a well-paid corporate position dealing, for instance, with the “analysis of digital traces of Islamic terrorism.”

Such a company was SCL (Strategic Communication Laboratories). SCL was founded in Britain in 1990, drawn and staffed directly from the British deep military-industrial establishment. For example, the director of the company’s defense operations department was Steve Tatham, who had served as head of psychological operations for British forces in Afghanistan. SCL developed as a private contracting company active in both the military and electoral sectors. The company’s military wing had contracts with both the American and British defense departments, among others. Its specialty was “psychological operations” – psyops, that is, manipulation through “information dominance,” a set of techniques including rumor spreading, disinformation, and fabrication of fake news. Through strategic manipulation, it had participated in Afghanistan and Pakistan in suppressing “jihadist violence” and limiting “recruitment by extremist groups”; it had served as a political advisor to states in sub-Saharan Africa, Southeast Asia, and South America in the area of national security; it had organized “psychological operations” on behalf of the British Army; it had a contract with the British defense ministry to conduct “anti-extremist” operations in the Middle East; it had contracts for influence campaigns supporting NATO among the population in Afghanistan and former Eastern Bloc countries; it had been involved in the elections of at least 200 developing countries, organizing campaigns to manipulate public opinion, while in others it had established comprehensive electronic surveillance and population monitoring systems.

Former employees of the company, who began to publicly speak out after March 17th and the revelations, speak of “a private” and additionally “dirty MI6”; while British secret services are formally overseen by a parliamentary committee and a prosecutor approves their actions, SCL was free to operate unchecked. The following excerpt from an interview with a former employee of the company in the Observer is characteristic:

“…Before we became this dark, dystopian data company that gave the world Trump, we were just a psychological warfare firm.” That’s what you called it, I ask him. Psychological warfare? “Absolutely. That’s what it was. Psyops. Psychological operations – the same method the military uses to influence behavior on a mass scale. That’s what they mean when they talk about winning hearts and minds. We did the same thing to win elections in developing countries where there aren’t many rules…”

In short, SCL was a regular, battle-ready branch of the British military establishment, and subsequently of the American one, whose methodology was taken straight from information operations manuals. In 2013, this company undertook the largest project in its thirty-year history: to work on the American presidential elections. Subsequently, another similar contract was added, for the British referendum on the question of leaving the EU. This private war company, then, when the mechanisms of the hard state core in the US and Britain were preparing for the great upheaval, found itself in a key role—with all the cyber warfare tools at its disposal.

Cambridge Analytica: the fifth dimension of the modern battlefield

A young Canadian nerd, brilliant in data analysis and trend prediction, seasoned in the backstage intrigues of the British political scene and with grand ideas around big data and their utility. A former banker and now editor-in-chief of the most hardline right-wing news site in the US, on a sacred mission to make American, white, petty-bourgeois fascism a hegemonic political force. And an American billionaire of the digital economy, head of a hedge fund, former pioneer of new technologies and main financier of the most far-right factions of the Republican Party. All three of them could be fictional heroes in John le Carré’s books or Norman Spinrad’s novel, “The Last World War.” However, they are real people. The first is Chris Wylie, who conceived, established, organized and directed the operations of Cambridge Analytica and lately attempts to cleanse himself, appearing in international media as a reformed whistleblower who revealed the Cambridge Analytica story in depth to the Guardian and the New York Times. The second is Steve Bannon, then editor-in-chief of the far-right news site Breitbart and subsequently strategic advisor to President Trump; in the meantime, he was the man who brought SCL to the US, took over its leadership and funded Cambridge Analytica as its vice-president. The third is billionaire Robert Mercer, owner of the hedge fund Renaissance Technologies, one of the largest donors to the Republican Party, the biggest financier of Trump’s pre-election campaign, close friend of British Farage, funder of the Brexit campaign (through provision of big data analysis services) and owner of Cambridge Analytica.

“I was the gay vegetarian Canadian who somehow ended up creating for Steve Bannon a psychological warfare tool that fucked with people’s minds.” This is exactly how Chris Wylie summarized his role in the Cambridge Analytica story. At the age of 24, while still doing his master’s thesis on predicting fashion trends, Wylie had already made a name for himself, working as a data analyst for the British Liberal Democrats (LibDem) party, when he was hired by SCL as research director for all the group’s businesses. The major challenge he had to face was SCL’s intention to expand its operations to America, ahead of the presidential elections, a plan for which the company was already collaborating with Steve Bannon through the newly formed Cambridge Analytica. The answer that Wylie began to formulate, influenced by Kosinski’s psychometric research that had just been published, was to combine big data with social media, applying the warfare methodology of information operations that anyway ran throughout SCL’s entire range of activities.

In the autumn of 2013, Wylie met Bannon, when the latter was still director of Breitbart, which he had brought to London in order to help Farage in the campaign for Brexit. In the interview Wylie gave to the Observer (18/3/2018), the description he makes himself is vivid and quite enlightening as to the atmosphere and intentions:

What kind of man was Bannon? “Smart,” Wylie replies. “Interesting guy. Really interested in ideas. He’s the only straight man I’ve ever spoken to about intersectional feminist theory. He immediately saw the connection to the oppression that conservative, young, white men feel.”

Wylie’s meeting with Bannon was like oil falling onto a flickering flame. Wylie had a theory to prove. At that point, the issue still had the dimensions of a theoretical problem. Politics is like fashion, he told Bannon.

“Bannon got it right away. He believed wholeheartedly in Andrew Breitbart’s doctrine that politics stems from culture, and therefore, to change politics, you must change culture. And fashion trends are a useful analogy for this. Trump is like a pair of Uggs or Crocs. How do you get people to go from thinking ‘ugly, totally hideous’ to everyone wearing them? That’s the approach he was looking for.”

It was Bannon who brought the Mercers into the game: Robert Mercer—managing director of the hedge fund Renaissance Technologies, who spends his billions promoting a right-wing agenda, funding the Republican Party and its candidates—and his daughter Rebekah. Nix [managing director of SCL] and Wylie traveled to New York to meet the Mercers at Rebekah’s apartment in Manhattan. “He liked me right away. ‘We need more people like you on our side,’ he kept saying.” People like you? What do you mean? “Gay people. He liked gay people. Bannon did too. He saw us as early adopters of his ideas. He believed that if you could convince gay people, everyone else would follow. That’s why he had such a connection with Milo [Yiannopoulos].”

The plan that Wylie proposed to Bannon and Mercer was becoming more concrete. To collect the Facebook profiles of millions of people in the US and use their personal and private data to create complex psychological and political profiles. Then, to target users with personalized “ads” designed specifically to work on their particular psychological profiles. What remained was to convince Mercer that such a plan was feasible, in order to secure his funding. And the most convincing argument was Cambridge Analytica’s own work. In 2013, one of the first contracts that CA undertook was in Trinidad. While SCL’s standard practice until then had been to take government contracts for some mock work, usually in the health sector, which served as a cover for setting up elections, in the case of Trinidad, CA negotiated directly with the country’s security council. The agreement included the development of a program for electronic micro-targeting of citizens, and the plan was for CA to record all telephone conversations and proceed with digital processing of the recordings, with the goal of creating a national police database, supplemented with the assessment of each citizen’s predisposition to commit criminal acts. The proposed plan was essentially Minority Report: the preventive suppression of crime at the level of thought. Trinidad was Cambridge Analytica’s first project using big data before the company was acquired by Mercer; and it was exactly this model that he bought.

«First we take Manhattan, then we take London»

With the company established and the plan ready, what was missing was the most critical part: collecting the data. The scale at which this collection needed to be done was staggering, since the goal was the psychological, digital profiling of the entire electorate—practically every adult—in the US and the UK. But Mercer’s millions now allowed Cambridge Analytica to throw a lot of money at the thorny problem of acquiring personal data.

Initially, Cambridge Analytica approached Kosinski and his team at the Psychometrics Centre. After all, he was the one who had developed the methodology combining the OCEAN model with personal data, had the most advanced techniques for constructing psychometric profiles, and furthermore, had at his disposal a massive, perhaps the largest, database of personal data collected through MyPersonality. Indeed, negotiations took place between SCL/CA and Kosinski, which, however, did not result in an agreement. Kosinski claims that he initially showed interest but backed out when he realized how shady the company’s operations were. A rather cheap excuse, admittedly, from a man whose own work made no claims to moral laurels and whose routine included regular collaboration with secret and military services. Moreover, the reality is that negotiations had reached the figure of 500,000 dollars, at which Kosinski would sell the database, but it holds that in the end, for some reason, he refused to agree. When the negotiations failed, another psychologist from the Psychometrics Centre, Aleksandr Kogan, offered a solution considered in academic circles as highly to extremely unethical. He offered to replicate Kosinski’s and his team’s research and exclude them from the final agreement. At Cambridge Analytica, this proposal seemed and proved to be the perfect solution.

Kogan indeed copied step-by-step the entire MyPersonality process: he placed ads for people who would be paid to participate in a personality quiz on Amazon’s Mechanical Turk and Qualtrics. In the fine print of Kogan’s quiz, which was named thisismydigitallife, there was the provision that participants granted access permission to their Facebook profiles (formally legal). But not only their own, but also those of their friends, unbeknownst to them. On average, each “seed” – the individuals who took the quiz, approximately 320,000 in total – without knowing it, opened the access window to the profiles of 160 other individuals, who had no idea nor suspicion of what was happening.

The company also (legally) purchased consumer databases – for everything, from magazine subscriptions to air travel – and in a unique way combined this data with psychographic data and voter files. It matched all this information with people’s addresses, their phone numbers, and even their email addresses. “The goal was to capture every dimension of voters’ information environment. Subsequently, all these personal data allowed CA to construct personalized messages” (from an interview with a former CA employee).

In November 2015, the most extreme of the two pro-Brexit campaigns—the Leave.EU campaign supported by Farage—announced that it had hired a Big Data company to support its digital campaign: Cambridge Analytica. A few months later, Trump had tweeted, somewhat cryptically, “You’ll soon be calling me Mr. Brexit.” The message seemed like sheer cunning—something that holds true for most of Trump’s messages—but alarming similarities had already begun to emerge between the pre-election campaign of the American presidential candidate and that of the far-right Brexit campaign. Similarities not so much in content, which were to be expected, but in methodology and practices. At that time, few would have paid attention to a small detail: that Trump had just hired a political marketing company, the same one running the far-right Brexit campaign. Cambridge Analytica, after being “planted” in the US by a subsidiary of the British military establishment, had returned to British soil to support Farage’s far-right racists, and from there it made its comeback, strengthened, to the US in service of Trump and “Make America Great Again.” If it were a military maneuver, we would call it a cyclical movement.

Until then, Trump’s digital campaign was subpar. It was run by a marketing businessman and failed startup creator, who had set up a basic website for Trump, costing $1,500. The 70-year-old Trump was and still is unfamiliar with technology; his personal assistant had once revealed that there was no computer in his office and that he didn’t even know how to send emails. She had convinced him to get a smartphone, from which he now tweets incessantly. Hillary Clinton, on the other hand, relied heavily on the legacy of the first “social media president,” Barack Obama. She had lists with the email addresses of all members of the Democratic Party, worked with pioneering Big Data analysts, and had the support of Google and DreamWorks. When it was announced in June 2016 that Trump had hired Cambridge Analytica, the establishment in Washington simply raised an eyebrow. Outsiders who don’t understand the country and its people? Seriously?

In September 2016, just a few weeks before the American elections, Alexander Nix, the managing director of Cambridge Analytica, had participated in a regular international conference, the Concordia summit, which is something like a miniature version of the World Economic Forum. At this summit, at a time still far from the “data theft scandal” and while Cambridge Analytica had gained a reputation almost as “communication wizards,” Nix gave a detailed presentation of his company’s capabilities. “In Cambridge,” he says in his speech, “we managed to create a model that predicts the personality of every adult in the US.” The audience is captivated. According to Nix, the success of Cambridge Analytica’s marketing is based on the combination of three factors: behavioral science based on the OCEAN model, Big Data analysis, and targeted advertising. Targeted advertising is personalized advertising, focused as much as possible on the personality of each individual consumer. Nix explains how his company achieved this. First, Cambridge Analytica buys personal data from a range of different sources, such as real estate records, purchasing activity, credit cards, club memberships, magazine subscriptions, and church parish participation. Nix presents logos of data trading companies such as Acxiom and Experian that operate globally—in the US, almost all personal data is for sale. For example, if you want to find out where Jewish women live, you can simply buy this information, including phone numbers. Subsequently, Cambridge Analytica combines this data with Republican Party voter lists and online data and builds a personality profile based on the Big Five. Suddenly, digital footprints become real people with fears, needs, interests, and home addresses. The methodology is the same as that developed by Kosinski at some point. “We have created the personality profile of every adult in the US—220 million people,” Nix boasts.

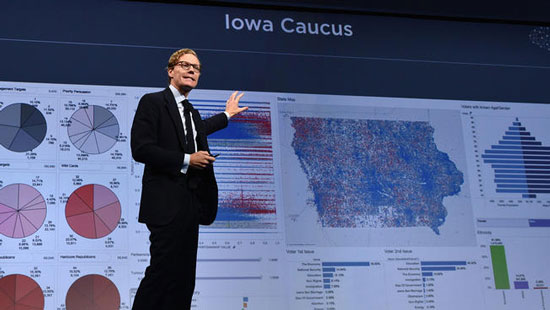

Nix continues the presentation and behind him a screen lights up. “This is the electronic control panel we prepared for Cruz’s campaign.” A panel with digital instruments appears. On the left there are diagrams; on the right, a map of Iowa, where Cruz made a surprise comeback and won a large number of votes in the primaries. And on the map are hundreds of thousands of small red and blue dots. Nix narrows down the criteria: “Republicans” – the blue dots disappear; “undecided” – more dots vanish; “males”… and so on. Eventually, only one dot remains, corresponding to a name, with age, address, interests, personal and political predispositions. Now, in what way does Cambridge Analytica target this specific individual with the appropriate political message?

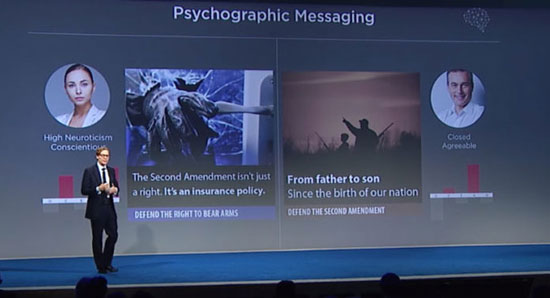

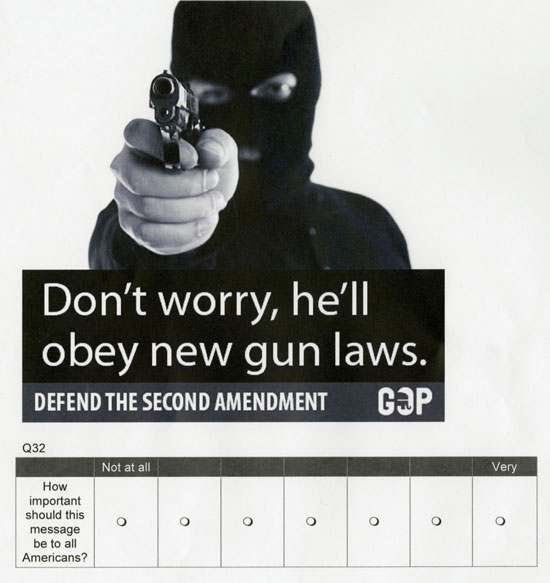

Nix now explains how psychographically categorized voters can be addressed differently, citing the right to bear arms, the Second Amendment to the Constitution, as an example: “For a highly neurotic and anxious audience, the theme of burglar intrusion threat—and the security that a gun provides—resonates.” The left image shows the hand of an intruder breaking a window. The right image depicts a man and a child standing in a meadow at sunset; both are holding guns and shooting at ducks: “Correspondingly, for a more traditional and receptive audience, this image fits: people who care about traditions and customs and family.”

Trump’s incredible contradictions, his much-criticized inconsistency, and the consequent series of conflicting messages are suddenly transformed into his greatest asset: a different message for every voter. The perception that Trump behaves like a perfectly weather-forecasting algorithm, following the audience’s reactions, is now beginning to take on literal meaning.

“Almost every message Trump sent was a product of data,” Nix had said in an interview. On the day of the third presidential debate between Trump and Clinton, Trump’s team tested 175,000 different advertising versions of his arguments via Facebook, in order to arrive at the appropriate one for each different group. The messages differed mostly at a microscopic level, in such a way as to exert the greatest possible psychological impact: different titles, colors, captions, positions of videos and photographs. The adaptation and refinement extended even to the smallest group level, Nix explained in the same interview. “We can address villages or housing complexes in a targeted way. Even individual voters.”

In Miami’s Little Haiti electoral district, for example, Trump’s campaign promoted local news stories about the Clinton Foundation’s failure after the Haiti earthquake, aiming to dissuade them from voting for Hillary Clinton. This, indeed, was one of the objectives: to keep potential Clinton voters (including hesitant leftists, African Americans, and young women) away from the polls, to “suppress” their vote, as a campaign insider told Bloomberg just weeks before the election. These “dark posts”—sponsored ads that looked like news in Facebook’s news feed and could only be seen by users with specific profiles—included videos targeting African Americans, in which Clinton referred to black men as predators, for example.

The methods used were radical. From July 2016, Trump’s canvassers were equipped with an app that enabled them to determine the political beliefs and personality type of a house’s residents. It was the same app used in the Brexit campaign. Trump’s team only rang doorbells of houses that the app flagged as receptive to the presidential candidate’s messages. The canvassers arrived prepared with tailor-made talking points suited to the resident’s profile. In turn, canvassers fed the app with the reactions they encountered, and the new data flowed back to Trump’s digital campaign headquarters.

Nevertheless, such methods are not entirely new. Democrats did similar things, although there is no evidence they relied on psychometric profiling. Cambridge Analytica, however, segmented the American population into 32 personality types and focused on 17 states. And just as Kosinski had concluded that men who like MAC cosmetics are slightly more likely to be gay, the company discovered that a preference for U.S.-made cars was an excellent indicator of a potential Trump voter. Among other things, the new findings showed exactly which of Trump’s messages worked best and where. The decision to focus on Michigan and Wisconsin in the final weeks of the campaign was made exclusively based on data analysis. The presidential candidate had become the perfect instrument for implementing a big data model.

a business has been completed, the cyberwarfare continues

The result of the British referendum in favor of Brexit and subsequently the electoral victory of Trump gave a great boost to Cambridge Analytica. Steve Bannon became Trump’s strategic advisor, while Michael Flynn, the first to be appointed to the position of national security advisor, had served as a consultant to SCL with a focus on lobbying the Pentagon and contracts with various services of the military-industrial complex. Cambridge Analytica itself saw its business prospects opening up. In the U.S., it began negotiations, with an unknown subject, with the Defense Department’s “multi-level assessment service,” a service whose work includes conducting psychological and sociological research in countries where the American military operates. In Britain, discussions were underway with Theresa May’s government in order to renew and expand SCL’s contracts with the Ministry of Defense, which had been a “client” for at least a decade. Alexander Nix, the prominent CEO of CA, had announced in various press interviews that the company had already received orders (for what subject?) from Switzerland, Germany, and Australia, while the company’s international client base continued to expand.

All of this until March 17, 2018, and the public reports in Observer (of the Guardian group) and New York Times that “burned” Cambridge Analytica. The story is so dirty that even its “revelation” looks like a chapter from some psyop. While there were documented publications about Cambridge Analytica’s activities long before – as early as 2015 – about the massive theft of personal data, about fake news campaigns, about electronic voter profiling, about the coordinated manipulation operation, it took the “soul” of the project, the person who conceived and organized the information operation, with papers and documents, to come into the spotlight. Consider this in relation to whistleblower Chris Wylie: Chelsea Manning, who leaked documents about American military atrocities in Iraq and Afghanistan, was sentenced to 35 years in prison on espionage charges. Edward Snowden, who revealed highly classified NSA programs, was treated as a traitor, is a fugitive, and lives in self-exile in Moscow. Wylie? “He’s eaten by guilt,” these are the consequences he pays, perhaps rewarded with a lucrative contract at some electronic economy company, and now enjoys fame. Something is rotten here…

We do not know exactly the reasons that necessitated such a journalistic campaign to expose Cambridge Analytica, but we can make reasonable assumptions, to the extent that internal competition within mechanisms is a given and not all factions agree on the attempted restructurings. It is indicative that the Observer covered the story as a coup, and such an accusation against the “oldest democracy” is not minor.

The first reaction of Cambridge Analytica was the expected one. It blamed the entire responsibility on the CEO, whom it sacrificed. When it became clear that a scapegoat would not bring about the “purification,” the SCL group announced in early May the bankruptcy of Cambridge Analytica and SCL Elections, leaving aside all other subsidiaries and branches that had been involved in the affair. But how feasible and realistic is it for a showcase company of the military establishment, essentially a ready-for-war unit, into which so much expertise has been invested and which carries years of operational experience, to dissolve at a time when the war has erupted? It is not! The bankruptcy is nothing but a misleading maneuver.

Indeed, that is exactly what happened. A few days before the bankruptcy filing, SCL executives established a new company, supposedly independent of the group, to which assets of Cambridge Analytica began to be transferred. Among those who set it up is former CEO Alexander Nix, as well as Rebekah Mercer among the directors.

And the name of the new company: Emerdata. Keep it in mind for future references.

Harry Tuttle