A favorite theme of science fiction (the entire The Matrix franchise is based on it) as well as discussions among “philosophers of mind”: what would happen if a brain could be sustained inside a vat with the necessary nutrients to keep it “alive” while at the same time being provided stimuli via electrodes? Would it truly be a conscious brain living inside a kind of Platonic cave, unaware that its experiences are constructed illusions? And should its experiences indeed be called illusions? Doesn’t the same thing perhaps happen with our own brains, with the only difference being that the body functions as an interface for delivering stimuli? In that case, perhaps we should speak of an illusory nature of reality itself. Profound questions that make careers, lead to university chairs, and fill the coffers of the mass cultural industry. The fact that they presuppose some far from obvious premises (a strict separation of the body from consciousness, which in turn implies a subject–object distinction for such a working hypothesis to even make sense) usually goes uncommented; even though such thought experiments can easily pave the way for a disguised obscurantism. Like that of The Matrix…

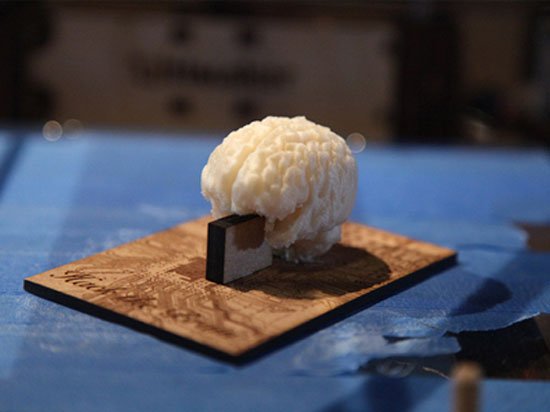

We will not remain at these high levels of philosophy. We will land in the reality of the 21st century and in real experiments conducted in real laboratories. They are called mini-brains in everyday speech and cerebral organoids in more technical terminology. These are real, biological neural networks grown in the lab and can remain alive for long periods of time. Having managed to control how human stem cells (the primary cells that, during embryo development, gradually differentiate to become specialized cells) develop, neurobiologists can now direct them to evolve into nerve cells, which not only remain alive, if provided with nutrients, but also form networks or even structures similar to those of the human brain. The technology is relatively recent, but it is making impressive progress. The lifespan of these mini-brains has been extended considerably, so today some of them can already celebrate their first birthdays. A year in the jar! The techniques that guide their evolution toward specific directions are also becoming increasingly precise. Some of them have even been implanted into rodent brains where they can have a longer lifespan. So far, no differences have been detected in the behavior and abilities of these “chimeric” rodents; no little mouse has yet managed to recite Rilke.

Such research is supposedly conducted for the better study of brain diseases. And indeed, these organoids may prove to be useful tools. However, an ethical debate has also emerged regarding the nature of these brain organoids. Do they have consciousness? What is the size and degree of complexity beyond which we should consider them as conscious beings that might experience pain? Should an ethical code of conduct be established, similar to that governing animal experiments? While the sensitivities of neuroscientists are moving, the key issue seems to lie elsewhere. This type of research represents exceptional tools for developing technologies that integrate biological material with electromechanical devices. The development of reliable interfaces between the body and information-processing machines is of strategic importance for the “smooth” transition to the next capitalist model: the one beginning to be called the Fourth Industrial Revolution.