At the beginning of the 21st century, the problematization of consciousness, in other words the formulation of questions such as “what is consciousness?”, could not belong to what has historically been called either “philosophy” or “religion” or “politics”. The current “bewilderment” stems directly from neuroscience. Specialists in imaging classifications and neurochemical theories already declare that they have satisfactorily explained the functioning of partial “brain mechanisms” (the word “mechanism” must be emphasized). Although every non-specialist should be cautious about what “explanation” means when, for its sake, something has already been presupposed that is understood as “mechanism” (therefore as machine), neuroscientists generally have no such reservations. Here is a sample of neuroscientific “naturalness”: 1

…What is it like to be a bat? Is the experience you have when seeing the color red the same as mine? In fact, how do we know for certain that other people have consciousness? I would say, however, that ultimately it is probably Neuroscience, and not Philosophy, that has the best chance of providing some answers to these very difficult questions.

A field in which we have made great progress is the discovery of the physiological and neurological correlations of consciousness – how consciousness “appears” in the brain, as one might say. One way to investigate this question is by observing what changes when consciousness is limited or absent, as occurs when people are in a vegetative state, without signs of consciousness.

Imaging examinations of the brain show that these people usually have damage to the thalamus, a transmission center for “signals” located right in the middle of the brain. Another common finding is damage to the connections between the thalamus and the prefrontal cortex, an area in the front part of the brain that is generally responsible for high-level complex thinking.

The prefrontal cortex has also been linked to consciousness through another method, brain imaging when individuals lose consciousness under general anesthesia. As consciousness fades, a distinct set of regions deactivates, with the prefrontal cortex being the most prominent absent region.

Studies of this kind have been invaluable in guiding us toward identifying the parts of the brain associated with being awake and conscious, but they still cannot tell us what happens in the brain when, for example, we see the color red.

Simply having someone lie in a brain scanner while looking at something red yields no result, because we know there is a large portion of unconscious brain activity caused by visual stimuli – in fact, by any sensory stimulus. How can we overcome this problem?One solution is to use stimuli that are exactly at the threshold of perception, which is why they are only perceived some of the time – playing a subliminal noise, for example, or displaying a word on a screen for an extremely short period of time, so brief that it is barely noticed. If the volunteer does not consciously perceive the word that appears, the only part of the brain that becomes activated is the one directly connected to the involved sensory organs, in this case the visual cortex. But if the volunteer does perceive the words or sounds, some other areas also become active. These are the lateral prefrontal cortex and the posterior parietal cortex, another area associated with complex, high-level thinking located at the top and toward the back of the brain.

Fortunately, despite the fact that many animals have a thalamus, the two cortical areas involved in consciousness are not as large and well-developed in other species as they are in humans. This fits with the widespread perception that, although there may be a spectrum of consciousness throughout the animal kingdom, our form of consciousness has something very distinctive about it.

In humans, the three brain regions involved in consciousness—the thalamus, the lateral prefrontal cortex, and the posterior parietal cortex—share a distinctive feature: they have more connections among themselves and with other brain areas than all other regions combined. With such dense interconnections, these three regions are the most suitable “candidates” for receiving, integrating, and analyzing information from the rest of the brain. Many neuroscientists suspect that this convergence of information is the key characteristic of consciousness. When I talk to a friend at a bar, for example, I don’t perceive him as a series of isolated features, but as a unified whole, combining his appearance with the sound of his voice, my knowledge of his name, his favorite beer, and so on—all concentrated into one unique person-object.

How does the brain bind together all these scattered pieces of information coming from so many different sources? The dominant theory is that the neurons involved begin to fire in synchrony many times per second, a phenomenon that can be observed as brain waves on an electroencephalogram (EEG), where electrodes are placed on the skull. The signature of consciousness appears to be a hyper-fast form of these brain waves, originating in the thalamus and spreading throughout the cortex.

…

The fact that the entire aforementioned sequence of observations and reasonings is historically and socially determined (electrodes and electroencephalograms are not eternal “tools” of human life/history!) would disturb the supposed “pure exit” from the sphere of somewhat foggy philosophy to the clean table (the “pure screen”) of science. And it would disturb it because it would strictly relativize both the question “what is consciousness?” and the answers: it is a valid question-and-answer procedure ONLY insofar as it is consistent with capitalist development (technical and political, primarily, though not exclusively) at the beginning of the 21st century. It is a valid question-and-answer procedure ONLY insofar as it is equipped with electrodes, electroencephalograms—and a certain jargon. It is, ultimately, a valid question-and-answer procedure ONLY insofar as the consciousness of neuroscientists is consistent with their capitalist (research, academic, commercial) environment.

Consequently, if there already exist – explanations – for – (brain) mechanisms, what is needed is a “unifying, universal theory / answer to the question of consciousness” that is compatible, consistent, with the basic “assumptions” of scientists and technologists (in general) at the beginning of the 21st century. It should be consistent, for example, with assumptions of the kind that, to begin with, everything is information and their processing…

A “universal information theory about consciousness” would thus be, not just favorably accepted by neuroscientists but something strategically more important: mandatory, compelling. No unrelated or hostile answer to the “question” towards the “information” of the 3rd and 4th industrial revolution would have a place; no matter how “philosophical”, “religious” or “political” it might want to be.

It cannot, therefore, be considered strange that such a theory was created! However, it is interesting (and the goal of criticism) how far such a “response to the question of consciousness” is forced, compelled to go…

a mechanizable “theory of everything”

The Italian Giulio Tononi, initially a psychiatrist and subsequently a neuroscientist, professor of psychiatry and sciences of consciousness at the University of Wisconsin, saw his fame skyrocket when he formulated the Integrated Information Theory – IIT for consciousness (“integrated information theory of consciousness”). What Tononi did not do was try to unify the findings of electroencephalograms into a single “map”. What he did was the opposite: he attempted to formulate mathematical-type axioms for the “being” of consciousness (and the experience of it)…

Essentially, Tononi hastily traversed the trajectory of “scientific thought” from the 19th century onward, which guarantees that once mathematical-type axioms are formulated for anything, their evolution into symbol strings is assured; with whatever subsequently entails the formation of “equations” that represent this anything 2.

The axioms that lie at the outset of IIT initially appear innocent:

– Internal existence: consciousness exists; every experience of it is in action. Indeed, that my conscious experience exists here and now (is real) is the only fact I can confirm. Moreover, my conscious experience exists from within its own internal perspective, regardless of external observers (it is internally real or in action).

– Structuring: Consciousness is structured. Every experience of it consists of multiple phenomenological distinctions, elementary or of a higher order. For example, within a conscious experience I can distinguish between a book, the color blue, a blue book, the left side, a blue book on the left side, etc.

– Information: Consciousness is informative. Every conscious experience exists in its particular way, constituted by a particular set of specific phenomenological distinctions, thus differing from other possible conscious experiences. For example, a conscious experience may include phenomenological distinctions that specify a large number of spatial positions, various positive concepts, such as bedroom (as opposed to non-bedroom), bed (as opposed to non-bed), blue color (as opposed to non-blue), higher-order compositions formed from first-order distinctions, such as a blue book (as opposed to a non-blue book), as well as many negative concepts, such as non-bird (as opposed to a bird), non-bicycle (as opposed to a bicycle), non-bush (as opposed to a bush), and so on. Similarly, the conscious experience of complete darkness and silence is constituted in a particular way—it has the particular quality that it has (not bedroom, not bed, not book, not blue, not any other object, color, sound, thought, etc.). And as this is the case, it necessarily differs from a large number of alternative conscious experiences that I could have but practically do not.

– Unity: Consciousness is unified. Every conscious experience is irreducible and cannot be subdivided into non-interdependent elements of phenomenological distinctions. I have the conscious experience of an entire visual field, not of its left side independent of its right (and vice versa). For example, the conscious experience of seeing the word BECAUSE written in the middle of an empty page cannot be reduced to the conscious visual experience of BE on the left plus the conscious experience of CAUSE on the right. Similarly, seeing a blue book cannot be reduced to seeing a book without blue color plus a blue color without a book.

– Exclusion: Consciousness is determinate, both in content and in spatiotemporal dimensions. Every conscious experience has the set of phenomenological distinctions that it has, neither fewer nor more, and flows at the speed that it flows, neither faster nor slower. For example, the conscious experience I have is seeing a body lying in a bed in a bedroom, or a shelf with books, one of which is blue. I do not have a conscious experience with less content, say one missing the distinction blue / not blue or colored / not colored. Nor with more content, say enhanced with the additional phenomenological distinction high / low blood pressure. Moreover, my conscious experience runs at a specific speed—let’s say it lasts a hundred milliseconds or so, but I do not have an experience that lasts a few milliseconds or, conversely, several minutes or hours.

It is possible that by following the above lines one might not notice that within their “naturalness” they are formulated in such a way that they can subsequently evolve into some kind of symbol strings. Perhaps the most immediately perceptible is the “axiom” of information integration of consciousness: it is evidently binary (bedroom / non-bedroom, etc.), something that is empirically arbitrary. However, this arbitrariness is strategically useful, since duality runs through the subsequent axioms as well. So that one can understand that Tononi’s axioms “describe” conscious states but in such a way that ultimately the axioms can evolve in some subsequent stage of his theory into “informational stimuli” and their management.

(No surprise. If things were otherwise, Tononi would simply be a little-known psychiatrist…)

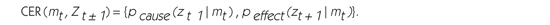

The above axioms must evolve into fundamental principles. We will not tire of reproducing them: fundamental principles are the evolution of axioms with more technical terminology. From the fundamental principles, equations are derived in the most natural way (like Athena from Zeus’s head) – the mathematical formulation of the basic characteristics of consciousness… You do not understand them, but you can admire them. Indicatively:

Or:

These are some mathematical formulas (let’s call them “equations” in the general sense of the word) for consciousness – according to Tononi and his followers. They look sufficiently “scientific” and completely incomprehensible. But that’s the jargon of techno-scientists. Incomprehensible to the uninitiated. We can, however, rest assured: our kind has turned the planet upside down; but it has finally realized what consciousness is…

What you shouldn’t miss, however, is the (Greek) letter phi. There are two such in Tononi’s theory. A capital (Φ) and a small (φ). The capital (Φ) is a measure of the integration (and hence the “informational complexity”) of consciousness – see the 4th axiom. The small (φ) is the minimum allowable division of this integration, which does not break the conscious complexity…

This is a well-meaning effort, but it could be useless. One can formulate “axioms” for consciousness, derive “fundamental principles” from them and arrive at mathematical formulas… However, something is missing, which was there from the beginning behind the question of consciousness, in the shadows but with dynamism; something that pushed this question (and the due answers) in the right direction, towards mathematical formulas, away from philosophical ambiguities. And this is the following: what is the relationship between electrons and all this?

Because yes, it would be extremely unfortunate if in the 21st century, the question of consciousness reached strings of symbols but remained a “property” (or “attribute”) of the living… What, after all, are the living? Matter. Therefore, all of the above should concern matter; and moreover not in its specific forms but in every form of it.

As another neuroscientist, named Christof Koch, put it:

“We are in the era of the birth of artificial intelligence and very critical questions arise: Can a machine have consciousness? Can it feel something? And if it has feelings, will it be entitled to legal rights and have moral obligations? Such questions we cannot avoid.”

Some Greek fans were delighted:

In his study on consciousness, Koch collaborated with Giulio Tononi… Tononi’s theory suggests that consciousness arises in physical systems that contain many different and highly complex interconnected pieces of information… Tononi attempted to measure “Φ” (the quantity of consciousness) in a human brain. The method he followed is similar to striking a bell. A magnetic pulse was sent into a human brain, and they observed how this pulse echoed among the neurons. The louder and clearer the echo, the greater the value of the quantity of consciousness. Using this method, Koch and Tononi were able to determine whether a patient was awake, asleep, or under anesthesia (data for verification).

The need to measure consciousness is urgent for both practical and ethical reasons. Doctors and scientists could use the “Φ” measurement unit to determine when an individual in a vegetative state has left life, the cognitive ability of a person suffering from dementia, how and when consciousness develops in an embryo, what and how animals perceive, and whether a computer can feel emotions.

…

The IIT theory also combines these practical applications with more profound ideas. The theory states that every object with “φ” greater than zero has consciousness. This may mean that animals, plants, cells, bacteria, and perhaps even protons in an atomic element are conscious beings….

While Tononi’s mathematical formalizations are incomprehensible, another aspect of his theory is easily understandable; although it could be considered cheap mysticism: this aspect is called panpsychism! Everything (everything, anything material!) “has a soul” – or, more correctly “has consciousness”. A chemical reaction can be considered a “conscious unfolding” of the molecules or even the electrons of certain materials, under specific conditions… As long as we can attribute a Φ to it…

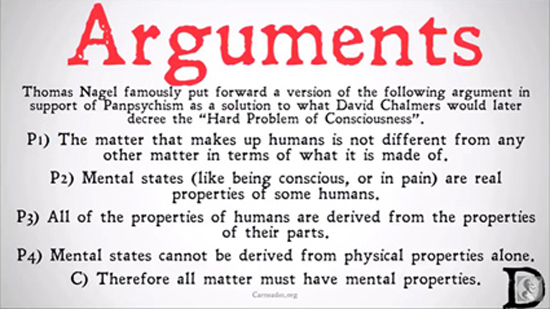

This aspect of Integrated Information Theory, namely “panpsychism,” seems the least random. However, it has brought forth various “old” arguments in its defense. From Plato to animism. Here, however, we are not concerned with advocating for the “panpsychist” investment of an information theory of consciousness. We are interested in what made it necessary (such an investment), against the risk of ridiculing its inspirers and supporters.

And this is clear: “consciousness” must be attributed to machines; or, which is the same thing, reasonable forms of mechanization of consciousness must be constructed. No matter how much this surprises non-experts, Tononi and his “panpsychism” are nothing more than a renewal (and practical adaptation) of ideas that almost 70 years ago one of the most famous “fathers” of cybernetics, Norbert Wiener, had. Note: 3

… The nervous system and the automatic machine are mechanisms which make decisions depending on the decisions they made in the past. The simpler mechanisms can choose between two solutions, such as opening or closing a switch. In the nervous system also each fiber separately decides whether to transmit a pulse or not. And in both cases, in the machine and in the fiber, there is a specialized device that forces future decisions to depend on previous ones. In the nervous system a large percentage of this transmission is fulfilled by those extremely complex points called “synapses”…

… This is the basis of at least part of the analogy between machines and living organisms. In the living organism the synapse corresponds to the switch in the machine. 4

… As I have said before, the machine, like the organism, is a construction which locally and temporarily appears to resist the general tendency toward increasing entropy. With the machine’s ability to make decisions, it can create around itself a local zone of organization in a world whose general tendency is to become barren…… Words like Life, Purpose and soul are completely inappropriate in pure scientific thinking… Every time we find a new phenomenon which participates to some extent in the nature of those we already call “phenomena of life”, but does not agree with all the related views that define the term “life”, we face the problem of broadening the word “life” so as to include them all or defining it in a more restrictive way so as not to include them… Now that certain behavioral analogies are observed between the machine and the living organism, the problem of whether the machine lives or not is, for our purposes, a matter of significance. And we are free to answer this, either one way or the other, as best serves our purposes. As Humpty Dumpty says about some of his most important remarks: “I pay extra for them and force them to do whatever I want”.

If we wish to use the word “Life” to cover all phenomena which move against the current of increasing entropy, we are free to do so. However, then we would include many astronomical phenomena which have only a shadowy similarity to life as we normally know it. Therefore, according to my opinion, it is best to avoid all indefinite expressions that raise questions, such as “life”, “soul”, “vitalism” and the like, and simply say that as far as machines are concerned, there is no reason why they should not resemble human beings in representing centers of decreasing entropy, within a framework where overall entropy tends to increase…

If Tononi makes a slight transgression with the “panpsychist” interpretation of his information theory of consciousness by using the term “soul,” it is only to the extent necessary to remain faithful to the spirit of Wiener’s views, since his subject is consciousness (and its mechanization)… Otherwise, “panpsychism” ensures such a theoretical approach to the question of what consciousness is that, by infinitely expanding the horizon (yes, even galaxies have some Φ…), it restores unity and analogy between “human,” “animal” in general, and “mechanical” being…

animism: the conscience of capital?

Even if Tononi’s theory and that of his followers, taken as a whole, remains just one among others (the struggle for dominance of one or another theory within techno-scientific “communities” is usually very fierce, even violent…), it is still relevant. We noted this in the previous issue 5: what are these machines that, in successive waves of techno-scientific capitalist revolutions, are endowed with “power,” “intelligence,” “sensitivity”—and, where applicable, with “consciousness”? They are a form of capital, a form of objectified labor; they are fixed capital.

Machines / fixed capital, “powerful or powerless,” “intelligent or stupid,” “sensitive or insensitive,” “conscious or unconscious,” are simultaneously two things: knowledge and labor that become objects, things; and means.

Regarding the first, they are completely opposite to each other—an approach, a conception (of whatever machine) that is phenomenological/behavioral, in relation to a historical/constructive conception. In the first case, the (whatever) machine can appear “powerful,” “smart,” “conscious,” simply and only because suitable (alleged) phenomenal similarities to something alive are indicated. We will see later why this indication (on the part of the manufacturers and owners of machines) is persistent, strategically persistent, for at least 1.5 centuries.

In the historical/constructive approach, on the other hand, everything is clear. The machine is knowledge and labor, and therefore it is necessarily an expression exclusively of this knowledge and this labor. The mathematical formulas about consciousness by Tononi, for example, are also an expression of a certain “scientific” theory; and as such, they can be deconstructed. A machine that incorporates these mathematical formulas will NOT demonstrate them; it will protect them from critical deconstruction; it will armor them and mythologize them; and in this way, it will seek to impose itself, to dominate over its living, human environment.

“It will seek to impose itself, to dominate…”? Why? Because the machine has a will to impose, a desire for dominance? No! Because its owner has such a desire!

Marx, in the well-known “fragment on machines” from the Grundrisse, notes:

… The science that compels the inanimate parts of machines to function purposefully as an automatic mechanism through their construction does not exist in the worker’s consciousness; on the contrary, it acts through the machine as a foreign force upon the worker, as a force of the machine itself…

Within a single sentence everything exists: science… the machine… its power… (human) consciousness… the imposition of the machine’s power upon the worker. We can and should enrich the above phrase by expanding the word “power” to include the concepts of “intelligence,” “sensitivity,” or “consciousness”; and the word “worker” by extending it to encompass all of social life.

The historical/constructive analysis reveals purposefulness. Not only of the characteristics and any function of any machine, but furthermore (which is most important) of the imposition via the machine upon life, from the side of its owners. Indeed, the machine is a means, in a dual sense: it is a means of improving performance (of labor or other vital characteristics); but on the other hand, it is also a means of control, a means of expropriating anything non-mechanical.

The attribution of consciousness to machines, the mechanization of consciousness, may appear technoscientifically as a highly complex, even farcical endeavor; yet politically, it is old, coherent, and militant. The attribution of consciousness to machines attacks any human consciousness by presenting the latter as a constituent of the former—and the former as “higher order” in contrast to the latter.

The political purposiveness (and not the technoscientific mannerism) of attributing consciousness to machines is well known to us. Elaborating on Marx6:

… In machines, knowledge [+ consciousness] appears as alien, external to the worker [+ the citizen]; and living labor [+ life as a whole] appears subordinated to the objectified [: machines / fixed capital], which possesses autonomous action. The worker [+ the citizen] appears as superfluous, to the extent that his action is not determined by the needs of capital…

Here, then, is the real political meaning of both capitalist “panpsychism”/animism and the “physio-logification” (that is: mythification) of the “consciousness of matter”—and therefore of electrons, algorithms, and “smart machines”:

1) Everything (from bosons to galaxies) is “alive”…

2) “Life” is a universal “anti-entropic” property of the universe, diffused wherever matter and energy exist in any form…

3) Correspondingly, “consciousness” is also diffused everywhere, as a self-referential property of material “anti-entropy”…

4) Physics and mathematics (as sciences of capital, as sciences of those who wish to be lords of life) can and must discover the “laws of consciousness,” just as they discover any other “physical laws”…

5) Once these “laws of consciousness” are constructed in such a way as to be mechanizable, life (in whatever real form and moment of it) is no longer a characteristic of the living, but a technological projection and application of science, hence fixed capital, hence property…

6) After this, life-life still exists… But it is merely a connecting element in the process of capitalist exploitation…

It is said that a factor in the rapid post-war technological development of Japanese capitalism, and specifically the ease with which robots, “artificial intelligence,” “robotic sex,” etc. are accepted, is Shintoism. Shintoism is the “indigenous” religion in Japan, and at its core is the worship of kami, which means “deities” or “spirits.” According to Shintoism, every living being, and even non-living things, has a kami. The totality of kami is called “yaoyorozu no kami,” which means infinite kami. Shintoism is animistic—and quite compatible with capitalism! Over 100 million Japanese people regularly or occasionally practice Shinto rituals…

Christianity appears as “monotheistic,” although in its main doctrines it is idolatrous. Formally, “God is one and only.” Practically, however, (Christian faith supports) many things have “power,” and therefore, in a particular way, “life”: icons, amulets, symbols, the bodies of “saints,” or even small pieces of them.

As an ideological backdrop to capitalism, Shintoism seems much more suitable to accept that consciousness is mechanizable, so “robots have souls too.” But Christianity won’t have much difficulty either, since everything is a creation of God.

And there is already agreement on who this is: capital in its various “incarnations,” mainly in the form of money.

Since fetishism is the “consciousness of capital,” mechanical animism can only be its most recent manifestation…

Ziggy Stardust

part of the tribute: neuroengineering: the gears of mechanical consciousness

- Bor Daniel, ephem. “the stage”, August 24, 2013, watching our mind in action. ↩︎

- More and in greater detail in notebook for worker use no 3, the mechanization of thought. ↩︎

- Norbert Wiener, Cybernetics and Society, the human use of human beings, Papadessa ed., 1970. ↩︎

- At this point, Wiener refers to the books “Design for a Brain” by W. Ross Ashby, from 1952, and “The Living Brain” by W. Grey Walter, from 1953. ↩︎

- Singularity: technological fetishism and political economy in the 21st century. ↩︎

- Grundrisse, volume B, p. 533 – “stochastis” edition. ↩︎