[ Original title: Foucault in Cyberspace, Surveillance, Sovereighty, and Hard-Wired Censors.

James Boyle is a professor at Duke Law School, where he teaches courses on intellectual property and the constitution in cyberspace, among others. He is a co-founder of Creative Commons and known for his positions in favor of relaxing intellectual property laws. ]

“The problems addressed by sovereignty theory were practically confined to the general mechanisms of power, to the ways in which its forms of existence at the higher levels of society influenced its exercise at the lower levels. In practice, the basic elements of the exercise of power could be determined by the terms of the sovereign-subject relationship. However, we have the emergence—or rather the invention—of a new power mechanism, with very specific procedures… which, in my opinion, is completely incompatible with these formal sovereign relationships… It is a form of power that is exercised continuously through surveillance, rather than through a system of impositions and obligations, intermittently and periodically…. It presupposes a dense network of material pressures instead of the physical presence of a sovereign. This non-sovereign type of power, which lies outside the form of sovereignty, is disciplinary power…” 1

This is an essay about law in cyberspace. I focus on three interdependent phenomena: a set of legal and political issues that I call the jurisprudence of digital liberty, a separate but related set of beliefs about the alleged inability of the state to regulate the Internet, and a preference for technological solutions to difficult legal issues of the Internet. I make the familiar claim that digital liberty is inadequate because of its failure to recognize the impact of private power, and the less familiar claim that digital liberty is incredibly short-sighted regarding the power of the state in cyberspace. In fact, I argue that the conceptual framework and jurisprudential claims of digital liberty have led its supporters to ignore the ways in which the state can often use private enforcement and state technologies to circumvent the alleged practical (and constitutional) limitations on the exercise of legal authority on the Internet. Finally, I argue that the technological solutions that appear as key solutions to the first two phenomena are neither neutral nor benign, as they are commonly considered today. Some of my examples come from current government proposals for regulating intellectual property rights on the Internet, while others come from the Communications Decency Act2 and the debate on cryptography. Along the way, I make occasional and unsystematic use of Michel Foucault’s recent work, to partly criticize the jurisprudential orthodoxy of the Internet.

The holy trinity of the internet

For a time, internet enthusiasts believed that it would be largely immune to state regulation. It wasn’t so much that national states wouldn’t want to control the network, but that they couldn’t do it; due to the technology of the medium, the geographical distribution of users and the nature of their content. This triple immunity became a kind of holy trinity of the internet, where faith in it was a prerequisite for acceptance in the community. Indeed, the ideas that I am about to discuss are so well known on the Internet that they have acquired the highest status that a culture can bestow: they have become clichés.

“The net 3 recognizes censorship as harmful and avoids it by choosing alternative routes around it”

This phrase by John Gilmore, one of the founders of the Electronic Frontier Foundation, has the dual advantage of being concise and technically accurate. The Internet was initially designed to survive a nuclear war. Its distributed architecture and packet-switching technology were built around the problem of delivering messages despite obstacles, holes, and malfunctions. Imagine the unfortunate censor facing such a system. There is no centralized exchange to control and rely on. Messages dynamically seek alternative routes, so that even if one path is blocked, another can be opened. Here lay the dream of the politically liberal: a technology with relatively low entry cost for both “speakers” and “listeners,” technically resistant to censorship, yet significant enough politically and economically that it cannot easily be ignored. The net offers obvious advantages to countries, research and other communities, and companies that use it, but it is extremely difficult to control the quantity and type of available information. Access is like a faucet that has only two settings: “off” and “full.” For governments, this is considered one of the greatest problems posed by the Internet. For Net devotees, most of whom support a variety of liberal ideas, the technical resilience of the Net against censorship—or any other externally imposed selectivity—is not “a bug, but a feature.” 4

“In Cyberspace, the First Amendment 5 is a local ordinance”

To the technical obstacles that the Net creates against externally imposed content filtering, geographical obstacles caused by its global expansion must also be added. Given that a document can be retrieved just as easily from a server five thousand kilometers away as from one five kilometers away, geographical proximity and the availability of content are independent of each other. If the king’s word can reach wherever his sword can reach, then a large part of the content on the net can be considered free from the regulation of any particular sovereign.

The libertarian culture that prevails on the net places state intervention in private action as necessary only for the prevention of “harms.” Viewing the net as a field of “human activity dominated by speech” where “harms” are comparatively more difficult, libertarians are far more opposed to state regulation of the digital environment than to the “meat-space” (note: meat-space, in contrast to cyberspace), as they mockingly call it. Their concession goes something like this: “wood and stones can break my bones, but bytes cannot harm me.” Therefore, the argument that a global net cannot be regulated by national governments was considered an unquestionably positive position.

The description of the first amendment to the constitution by John Perry Barlow as a local institution reminds us that it is not simply about “bad” state traditions, interventions and regulations that are rendered obsolete in cyberspace. There is a difference between speech that is constitutionally protected and that which may be practically/technically uncontrollable. Indeed, the second situation may in some cases undermine the protection of the first situation.

“Information wants to be free”

For someone interested in political theory, one of the most striking things about the net is the instability of political mapping. We divide our world into related and opposing territories – public and private, property and sovereignty, state regulation and laissez-faire – “solving” problems by examining their position on this map. In the everyday world, these divisions seem relatively stable and coherent to most people, even if some smart academic critics may insist on their theoretical indeterminacy. On the net, things are different. Concepts and political forces seem blurred. Nothing demonstrates this point better than the discussion regarding online intellectual property. In the digital environment, is intellectual property simply property, that is, a prerequisite for an unregulated market or yet another example of rights that libertarians believe the state was specifically created to protect? Or is intellectual property actually a public regulation, artificial and not natural, an invented monopoly imposed by a sovereign state, an intervention that distorts and reduces freedom in an otherwise free market?

While it would be difficult to find someone who fully believes in either of these two stereotypes, recognizable versions of both can be found in the discussion on intellectual property and – even more interesting – they can be found across the entire political spectrum. George Gilder of the conservative Manhattan Institute, a fervent supporter of capitalism and laissez faire, displays considerable skepticism regarding intellectual property. Peter Huber, from the same conservative think tank, views it as the cornerstone of freedom, privacy, and natural rights. The Clinton administration seeks to expand online intellectual property rights and faces strong criticism from both civil liberties groups and right-wing intellectuals. This is not merely a disagreement over tactics among people who could be said to share the same ideology: it concerns a fundamental set of disputes regarding the social structure itself and the regulatory significance of a particular phenomenon – as though the liberal party could not agree on whether its slogan should be “Taxation is theft” or “Property is theft.”

Stewart Brand’s phrase “information wants to be free” has penetrated culture so deeply that it can now even be a cliché in advertisements. However, its ubiquitous nature may serve to obscure its claims.

John Perry Barlow begins his famous essay “Selling Wine without Bottles: The Economy of the Mind in the Global Network” with this excerpt from Jefferson:

“If nature has made anything less susceptible than all others to exclusive property, it is the action of the power of thought called idea – which an individual can exclusively possess as long as he keeps it to himself. But the moment it is revealed, it forces it to become the property of all, and the recipient cannot be deprived of the knowledge of it. A characteristic of its peculiar nature is also that no one possesses less, because everyone else possesses the whole of it. He who receives an idea from me, does not diminish mine – just as when someone lights his candle from mine, he does not leave me in more darkness. The fact that ideas must spread freely from one to another throughout the world, for the moral and mutual instruction of man and the improvement of his condition, seems to have been specially and benevolently designed by nature, like fire which extends throughout space without diminishing its density at any point, and like the air which we breathe, in which we move and have our physical existence – unable to confine it or acquire it exclusively. Inventions cannot, by their nature, constitute an object of property.”

This statement absolutely expresses the mixture of Enlightenment values and the fundamental theory of public goods that “net analysis” represents for information flows. Copying information costs nothing. It must spread widely and cannot be restricted. Beyond a Jeffersonian faith lies a kind of Darwinian anthropomorphism. Information really wants to be free. John Perry Barlow refers to Brand’s phrase:

“…recognizing both the natural desire of secrets to be told and the fact that they could constitute from the outset something like a ‘desire’. The English biologist and philosopher Richard Dawkins proposed the idea of ‘memes’, self-replicating forms of information that spread among the ecology of minds, as if they were forms of life. I believe they are forms of life from every perspective except their basis in the carbon atom. They self-reproduce, interact with their environment and adapt to it, mutate, persist. Like any other form of life, they evolve to fill the potential spaces of their local environments, which in this case are the belief systems and cultures of their carriers, that is, us. Indeed, sociobiologists like Dawkins make a reasonable assumption that carbon-based life forms are also information. Just as the chicken is a way for the egg to make another egg, the entire biological spectrum is simply the means for DNA to copy more information like itself.”

From this perspective, it appears that the net is the absolutely natural environment for information and that the attempt to regulate it is like trying to hinder evolution.

Overall, these three positions confirm that the technology of the medium, the geographical distribution of its users, and the nature of its content make the Net particularly resistant to state regulation. The state is excessively large, too slow, and too geographically and technically limited to regulate the fleeting interactions of a citizen within this volatile medium. Although I do not agree with the full version of these positions, I have a sympathy for each of them. I am enthusiastic that the net is extremely resistant to content filtering imposed from outside—although I worry about structural private filters as well as public ones under orders—and I acknowledge that reason and information can and will cause both harm and good. I believe that the global character of the Network is—by and large—something positive, although we must pay greater attention to things like the cost of the technology required to play the game, or the impacts on workers in a networked economy where companies relocate around the world and can find an online workforce within an afternoon. 6 Finally, I feel optimistic about the historical combination of technologies based on nearly cost-free copies and a political tradition that treats information in a more equitable way than other resources. It is certainly possible to create a world where the unchecked kleptocracy of information undermines scientific and artistic development. I have argued elsewhere that the main risk is not that information will be too free, but that intellectual property rights will become so exhaustive that they will truly stifle innovation, freedom of speech, and the dynamics of education. In any case, I want to set aside my agreement or disagreement with the values of Network theology and focus on the practical and legal cases upon which it is based. My argument is that information libertarians should not dismiss the state so easily. In fact, I argue that the work of the peculiarly non-digital philosopher Michel Foucault provides some useful ideas about the ways power can be exercised on the Internet and the reasons why many contemporary analyses are so dismissive of the power of law and the state.

Foucault and the Doctrines of Digital Freedom

When netizens think about law, they tend to create a positivist, even “Austinian7 image8” · law is a command backed by threats, issued by a sovereign who recognizes no superior, and addressed to a geographically defined population that obeys it. Thus, they consider state laws as clumsy tools that are unable to enforce their will on the global issues of the Net and on its ephemeral and geographically shifting transactions. Indeed, if any model of law were to fail to regulate the Network, it would be the Austinian model. Fortunately or unfortunately for the Net, however, the Austinian model is inept and inaccurate. And this is where the recent work of Michel Foucault comes in.

Michel Foucault was one of the most interesting post-war French philosophers and social theorists. His work was extensive, sometimes obscure, and his historical generalizations would be inapplicable if they weren’t so frequently provocatively useful. Above all, Foucault had the ability to pose problems in a new way – redirecting research in a manner that was particularly helpful to those who followed. This usefulness is evident even from thinkers whose politics and methodology differ greatly from Foucault’s.

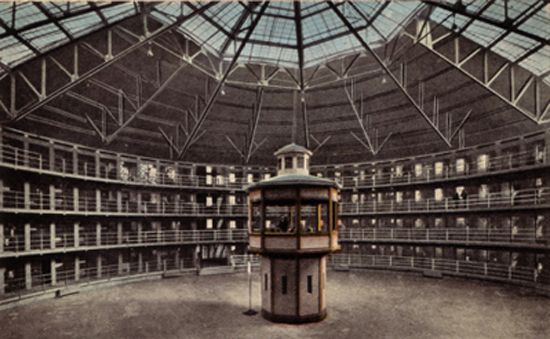

For the position of this particular article, one of Foucault’s most interesting contributions is his questioning of a specific concept of power, power-as-sovereignty, and his opposition to it through surveillance and discipline. At the core of this work was the belief that both our analyses of how political power operates and our strategies for limiting it were inaccurate and flawed. In a series of essays and books, Foucault argued that instead of the familiar and official triangle of sovereign, citizen, and right, we should focus on a series of finer, private, informal, and material forms of coercion organized around the concepts of discipline and surveillance. The example for the idea of surveillance was the Panopticon design, Bentham’s plan for a prison constructed in a circular form around a central tower from which the observing guard could at any moment have the prisoner under observation. Uncertain whether the guard is watching, the prisoner will constantly try to adjust his behavior. Bentham had found the behavioral equivalent of the superego, formed by the uncertainty of when someone is being watched. The echo of contemporary laments about the “lack of privacy protection” is deafening. To this, Foucault added the concept of discipline—which organized the multiple “private” methods of regulating individual behavior, ranging from instructions for more efficient use of motion and time at work to psychiatric evaluation.

Foucault highlighted the apparent conflict between an official language of politics organized around the relationships between sovereign and citizen, which is expressed through rules supported by sanctions, and a real experience of power exercised through numerous non-state sources, which often depend on material or technological means of enforcement. Writing in a way that managed to be both cunning and threatening, Foucault suggested that there was something strange in the coexistence of these two systems:

“Impossible to describe with the terminology of sovereignty theory, from which it differs so radically, this disciplinary power should have as a result the disappearance of the great legal edifice that has been created by this theory (of sovereignty). But in reality, the theory of sovereignty continues to exist not only as an ideology of right, but also to provide the organizational principle of legal codes… Why did the theory of sovereignty persist in this way…? For two reasons, I believe. On the one hand, there was a permanent means of criticizing monarchy and all the obstacles to the development of a disciplined society. But at the same time, the theory of sovereignty and the organization of a legal code focused on it allowed a system of rights to cover the mechanism of discipline in such a way as to hide its real processes…”

Foucault does not write about the internet. He doesn’t even write about the twentieth century. But his words provide a good starting point from which to examine the catechism about the inviolable net. It is a good starting point precisely because, when examining sovereignty, the issuing and implementation of Austinian “commands supported by threats and aimed at a specific area and population,” the net indeed appears almost immune. However, things look somewhat different from the perspective of “a type of power that is exercised continuously through surveillance rather than intermittently through a system of commands and obligations at intervals, and which presupposes a dense mesh of material constraints instead of the physical presence of a sovereign.” Moreover, there is a concept according to which “the system of rights extends into the mechanism of discipline in such a way as to conceal its actual processes.” The jurisprudence of digital freedom is not simply inaccurate, but may also obscure our understanding of what is really happening. Thus, even the digerati 9 may find the following analysis interesting. If for no other reason, to see how the net can come to treat censorship as “a feature and not a bug”; how far local orders can reach into cyberspace; and how the “desire for information freedom” can be curtailed.

The examples I will give 10 come from different areas of telecommunications regulation. Some of them clearly deal with the Internet: the Communications Decency Act (CDA), the proposed NII Copyright Protection Act, and cryptography regulation. Others address technologies outside of the Net, at least for now: the V-chip, the Clipper chip, 11 digital telephony, and digital audio recorders. All of them have one thing in common – the state actively worked to embed or anchor the legal regime directly into the technology itself. In most of these cases, the exercise of power is much more a matter of parallel shaping and monitoring of activity rather than simple post-facto imposition of regulations. However, these examples also reveal significant differences – depicting a range of objectives, tactics, and outcomes. Sometimes technology has been mandated by legislation, sometimes facilitated through state sanctions. Sometimes legislation defines technological safe harbors from sanctions that would otherwise apply, and sometimes the state uses its economic power to create a de facto standard, refusing to purchase equipment that does not comply with desired technical/legal standards. I will start with the Communications Decency Act, turn to the use of strict liability and digital fences in Internet copyright policy, and conclude with a sample of embedded regulation, drawing examples from various areas of communications technology.

Safe harbors and unintended consequences

The Communications Decency Act is considered the supreme law of Congress’s legislation on communication technologies. As poorly designed, articulated without coherence, and apparently unconstitutional, it appears to the majority of the internet community as a case of unchecked technological ignorance. Congress wanted to regulate something it did not understand, since a percentage of the content originated outside the jurisdiction of the United States. Reactions ranged from ridicule over Congress’s lack of technological knowledge to anger at the law that attempted to exercise power over electronic borders. “Keep your laws out of our network” was the slogan.

When the CDA was rejected by two different three-member judicial panels and subsequently unanimously by the Supreme Court, the decisions were considered as an inevitable vindication of these libertarian views. The fact that the lower court rulings were based on constitutional issues arising for the CDA because it could not be enforced over much of the content on the internet simply facilitated the victory. Federal judges had indeed recognized both the technical resilience of the net to censorship and the fact that a global network could never be effectively regulated by national legislation. Thus, two of the three parts of the “internet holy trinity” were recognized by federal authorities. Moreover, they had been incorporated into the analytical framework of the First Amendment. Given that the CDA would likely have been ineffective, can we say that it passed the strict scrutiny of the First Amendment? Was it not a case of substantial restriction of “freedom of speech,” without effectively achieving the compelling state interest?

From the perspective of digital liberty jurisprudence, these reactions were absolutely justified. An order supported by the threats of a sovereign, targeting a geographically defined population, had been met and destroyed by the citizens’ right against state intrusion, partly due to the sovereign’s inability to control those beyond its borders. The Communications Decency Act vanishes as if it never existed—an absolute failure. However, this analysis overlooks developments around the CDA: not the public criminal penalties, but the shaping and development of privately deployed, material technological methods of surveillance and censorship.

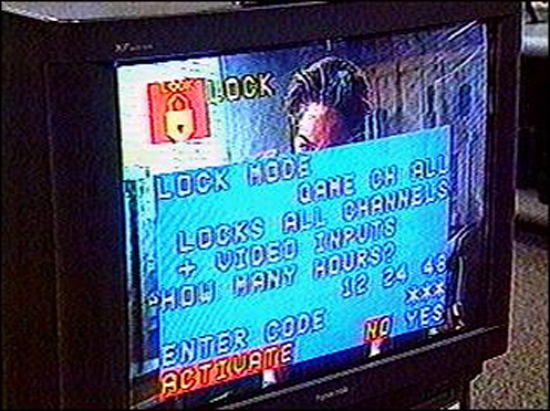

The Communications Decency Act (CDA) aimed at protecting minors from indecent material. However, if it did so by effectively restricting the speech of adults, it would be considered an unconstitutional overreach. 12 The CDA’s response to this issue was to create “safe harbors” for indecent but constitutionally protected content aimed at adults, so that it would not be accessible to minors. The law offered various methods to achieve this goal, such as “the use of a verified credit card, debit account, adult access code, or adult identification number.” Given the technology and economy of the net, however, the most significant safe harbor for non-profit organizations would be the one provided by section 223(e)(5)(A): immunity offered to those who used “any method feasible based on available technology.”

Here is where the irony begins. When the Communications Decency Act was first proposed, several computer scientists and software engineers decided to do more than simply call against its unconstitutionality. They were convinced that an answer to the need for regulation could be found in the language of the net itself. I do not use the term “language of the net” as part of some deconstructive or Saussurean allegory—the idea was literally to create a filtering system whose filters would be embedded in the language that enables access to the World Wide Web, the Hyper Text Markup Language or HTML. Viewing technical solutions as inherently preferable to the exercise of state power, and as facilitating private choice rather than public sanctions, they offered an alternative solution aimed at proving that the CDA was, above all, unnecessary. The idea is called the Platform for Internet Content Selection (PICS) and allows tags that rate a website to be embedded in meta-file information within the page itself. It can be adapted to provide for third-party rating and is considered “value-neutral,” as it can be used to promote any value system. Websites could be rated for violence, sexism, adherence to a particular religious faith, or any set of criteria deemed appropriate. The third-party rater could be the Christian Coalition, the National Organization for Women, or the Society for the Preservation of Zoroastrian Truth. Of course, in practice, the PICS technology might be used disproportionately to favor one particular set of ideas and values and exclude others, just as perhaps occurs with the Lochner-era “freedom of contract” regime, where some groups are favored over others, despite everyone being “value-neutral.” But this legal obsession with examining actual outcomes and real rather than formal power is far less part of the First Amendment’s concern and far more a matter of private law.

While PICS and a variety of other systems offered a technical solution from the “speaker’s” side, other software programs also offered technical solutions on the “listener’s” side. These programs would not offer speakers a safe harbor from the law. Instead, they would “empower” computer users to protect their families from unwanted content through the use of filters, thereby increasing the hope, in the hearts of libertarians, that the CDA was unnecessary. Programs such as SurfWatch, CyberPatrol, NetNanny, and CyberSitter would block access to inappropriate material and would do so without requiring continuous parental intervention. These programs typically maintained a list of forbidden sites, as well as a text search filter that would exclude documents containing forbidden phrases/words.

The irony I mentioned is that these technical solutions were used by both sides of the CDA dispute. Those who challenged the CDA argued that the availability of privately implemented technological solutions meant that the CDA had not been substantially examined, based on the First Amendment: ultimately, these means were not less restrictive in achieving the goal. With the “audience” exclusion software, parents were allowed to control what their children saw, while with “speaker” rating systems such as PICS, a private solution was offered to the problem of evaluating content on the Internet.

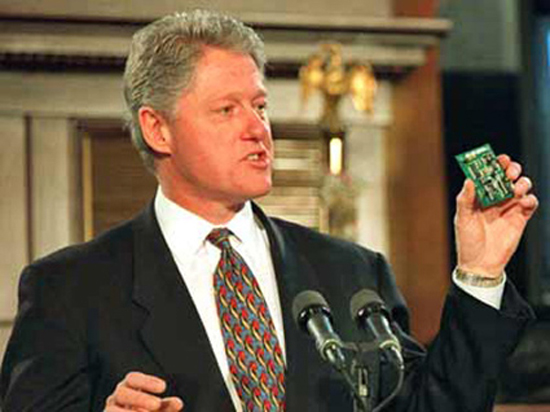

The government took the opposite position, arguing that the availability of systems such as PICS meant that the CDA ultimately did not constitute an overbroad generalization. Adult “speakers” would not be burdened by the law, because these systems would provide sufficient methods to separate their indecent speech from the eyes of minors. The Supreme Court ultimately disagreed, although Justice O’Connor left open the possibility that future technological developments could reshape this conclusion. Even before the decision was made, President Clinton had already expressed his political preference for a technical solution to the issue of regulating online communication, speaking vaguely about a “V-chip for the Internet.” Bills have already progressed in Congress, according to which Internet service providers will be required to provide filtering software to customers and to aim at developing an “E-chip.” 13

Where does online communication stand after the Supreme Court’s decision? From the perspective of digital freedom, the net remains unregulated and the Internet’s “Holy Trinity” undisturbed. From the viewpoint I have developed here, things seem more complicated. As the CDA was constitutionally sidelined, technological solutions emerged—some because of the CDA and some despite the CDA. In contrast to the extensive attention given to the CDA, much of this process was effectively isolated from careful scrutiny due to the perceptions of law and state that I explore here.

[…]

Conclusion

Looking from Foucault’s side, the examples I gave in this article seem to show two conclusions, which may seem paradoxical. On one hand, the assumption that the state will not be able to regulate cyberspace is absolutely shortsighted in relation to some of the most significant ways in which states can actually exercise power. The jurisprudence of digital freedom should use much less John Austin and much more Michel Foucault. But we should not simply limit the analysis to the available possibilities of state power. “Discipline and Punish” was not a manual for state officials, but a challenge – in some ways similar to the challenges posed by legal realism and feminism – to the very notions of public and private, and to the belief that power begins and ends with the state.

If the first conclusion of this study is that the state can actually have more power than digerati believe, the second conclusion is that the appeal of technical solutions does not simply stem from the fact that they work, but from the fact that they largely bypass the issue of power—both private and public. Technology is presented as “the way things are.” Its origins are obscured, whether it originates from state-sponsored schemes or from market structures, and its effects are unclear because it is difficult to imagine the alternative. Above all, technical solutions are less controversial; we perceive a legal regime as coercive and a technological regime as simply shaping—or even actively facilitating—our choices.

During the Lochner era, a strikingly similar contrast was observed between the coercive nature of public law and the free private world of a market merely shaped by neutral, favorable contract and property rules. Legal realists did an excellent job highlighting the shortcomings of this market image. If we want to have alternatives to the jurisprudence of digital libertarianism, we must offer a richer picture of Internet politics than that of a pushy (but powerless) state and neutral, facilitative technology.

translation, adaptation: Wintermute

part of the tribute: surveillance and discipline in the 4th industrial revolution

- Michel Foucault, Two Lectures, Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings, 1972-1977. ↩︎

- The Telecommunications Act of 1996. ↩︎

- [transl.] In various points we keep from the original the characterization of the internet as net – the word preferred by “internet residents” or otherwise netizens (references below). ↩︎

- [Source: Wikipedia] The expression “not a bug but a feature” is used in the programmers’ community to declare that a characteristic (feature) or behavior of a program may seem problematic or dysfunctional to some users, but in reality it has been intentionally designed that way and is not a programming error (bug). ↩︎

- [Source: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration] The “first amendment” to the U.S. Constitution prohibits American governments from legislating against freedom of speech, public expression, religious choice, the press, the right of assembly, etc. It was adopted on December 15, 1791, as one of the ten constitutional amendments that constituted the “Bill of Rights.” It is considered the institutional guardian of fundamental freedoms in the U.S. ↩︎

- The global rapid mobility of the workforce is not something that Adam Smith had thought of; is it a quantitative or qualitative distinction? ↩︎

- [st.m.] Refers to John Austin (1790-1859), an English legal theorist who founded the theory of legal positivism. ↩︎

- One of the reasons for this may be the overwhelmingly liberal positions on political issues of the Internet in the United States. Liberals tend to focus on state power rather than private power, tend to focus on the obvious restrictions on freedom imposed by the impact of criminal law on the citizen, rather than the finer restrictions imposed by the rules that constitute and structure the relationships of the market, and not only. Both ideas “fit” with the Ostinika image. By making a criminal regime the standard of exercising state power and the right of the citizen against the government the standard of restriction, the liberal encodes his regulatory ideas about political problems and their solutions in the image of the law itself. ↩︎

- [abbr.] Term that characterizes people with specialization and/or professional training in computer science. ↩︎

- [pp. 127-128] We present the first of the three examples given by Boyle, partly for economy of space and partly because we consider it sufficiently supports his positions. ↩︎

- [edit] The V-Chip was a technology with which one could block television programs based on certain criteria. The Clipper chip was an NSA chip that encrypted data and assigned a unique number to each communication device. ↩︎

- [Editor’s note] “Unconstitutional as overbroad” in the original. In a sense, unconstitutional because it “goes beyond the waters of the constitution.” ↩︎

- [transl.] Equivalent of the V-chip, for the Internet. ↩︎