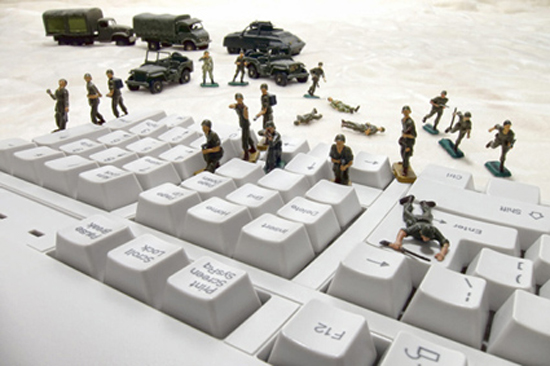

A characterization consistently attributed to the fourth world war, even by those who refuse to recognize it as such, is that of hybrid war. Hybrid, because orthodox and unorthodox methods converge and intertwine, conventional and modern forms, formal and informal conflicts. The cyberspace factor, with its hegemonic dominance across the entire social spectrum, is what most of all has imparted the hybrid character to war. Strategies are specifically deployed for the digital arena, campaigns are organized, battles unfold, strikes occur, and all this in an imperceptible way, behind the massive playground of social media.

Israel is among the states at the forefront of cyber warfare; in fact, it claims to be such and advertises itself as such, without any measure of comparison or verification of its claims. Without making a fuss about it, it is a given that a number of states, especially those taking part in confrontations, have developed their own cyber warfare techniques. The difference of the Israeli state from the rest in the digital “arms race” is that it has the largest testing ground under real conditions. The occupied Palestinian territories, the world’s largest prison, is the “laboratory” where Israeli forces, besides applying the utmost of their murderous power, test all their new technologies. The two articles below are indicative of the cyber warfare techniques developed by the Israeli state. The first was published on April 16 in the online magazine One Zero. The second was published on June 5 in the also digital Wired.

Harry Tuttle

Israel’s hidden cyber-power reshapes the Middle East

As Israel’s digital surveillance sector continues to grow, questions are beginning to arise about who this technology empowers.

“New revelations about torture in the prisons of the Emirates.” This is what a message read that was sent to the iPhone of Ahmed Mansoor, a prominent human rights activist in the UAE. The message contained a link, which Mansoor did not click. Suspecting previous attempts to hack his communications, he forwarded the message to a cybersecurity researcher at the organization Citizen Lab, which deals with digital rights issues. What happened next would be a crucial point in a story that is invisibly reshaping the Middle East.

Based on Citizen Lab’s research, the link led to spyware manufactured by the Israeli technology company NSO Group. According to Citizen Lab, the existence of the spyware signals the ongoing disregard of such companies for human rights issues. Under Israeli law, NSO Group should have had a license to sell its products to the UAE. “The systematic violation of human rights by the UAE,” writes Citizen Lab, “should not have carried the same weight as other motives of the authorities who licensed the export.”

Since then, NSO Group and the Pegasus spyware have been linked to the surveillance of politicians and journalists in the UAE, and last March, security expert Gavin Becker claimed that the spyware had been used to monitor Jeff Bezos of Amazon. Pegasus also appears to have played a role in the murder of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi. However, NSO Group has denied that its programs were used in espionage against Khashoggi or Bezos.

In a statement, a spokesperson for NSO Group said that the company complies “with all relevant laws and regulations” and has established a business ethics committee to ensure that its technologies are used responsibly. “We do not tolerate misuse of our products, and we regularly review and revise our contracts to ensure they are not used for anything other than preventing or investigating terrorism and crime.”

But Israel’s cyber-espionage industry goes far beyond one spyware. Last October, an investigation by the Israeli newspaper Haaretz revealed numerous Israeli companies selling offensive and defensive cyber-espionage and surveillance programs to countries around the world, many of which employ highly controversial methods regarding human rights issues. (…)

According to the website Intelligence Online, the company AGT International – based in Switzerland and owned by Israeli businessman Mati Kochavi – signed a contract with the UAE in 2008 worth over 800 million dollars for a wide-range surveillance and security system to protect oil and natural gas facilities. More recently, the same company was found to be involved, through a Swiss intermediary, in a secret security cooperation with the UAE, involving a political monitoring network in Abu Dhabi titled “Falcon Eye”. According to some sources, this system guarantees that “every individual is monitored from the moment they leave their door until they return”.

Another Israeli company, IntuView, created an electronic program for Saudi Arabia in 2015 aimed at identifying jihadists on social media. The program was capable of processing 4 million Facebook and Twitter posts daily, and later added the ability to monitor public opinion trends regarding the royal family. According to Haaretz’s investigation, Verint Systems, an analytics company with nearly half of its employees located in Israel, sold a similar system to Bahrain.

Neve Gordon, professor of international law at the English university Queen Mary, believes that these exports have a significant impact on the power dynamics in the region. “Regimes such as Saudi Arabia and other Gulf states today feel more comfortable with Israel than with the other Arab countries in the region. We may not see it at the official political level, but it certainly applies in the field of the military industry and private security companies. We see the relationships between these countries being shaped through the buying and selling of products related to surveillance and security. We could even say that the reshaping of the Middle East is happening through this industry.”

how Israel found itself at the forefront of cyber

Israel takes cybersecurity very seriously. The country ranks second globally in cybersecurity contracts, only behind the USA. In 2018, the total amount of investments in Israeli cybersecurity companies recorded an annual growth rate of 22%, reaching $1.03 billion. The previous year, the government announced it would invest $25 million in the industry and launch a three-year program for pilot application investments in companies working on “high-risk” research and development. In the field where cybersecurity, surveillance, and security intersect, Israel is a reference point. (…)

Israel is the country where some of the first firewall software companies were founded, such as the multinational digital security company Check Point. It is also on this same ground that Israel’s offensive cyber capabilities were developed. In 2010, a powerful virus was revealed, attributed to attacks on five Iranian industrial facilities over a period of 10 months. The targets included uranium enrichment facilities in Natanz, and all researchers have concluded that the virus, named Stuxnet, was the result of a joint effort between the USA and Israel.

The issues become quite complicated when taking into account the relationships between the Israeli cybersecurity industry and the Israeli army. One of the many characteristics that most companies have in common, from Check Point to NSO Group, is a strong link between their founders and the IDF [the Israeli army]. (…) A specific branch of the IDF has particularly close ties with the Israeli cyber industry: Unit 8200, responsible for surveillance and security [8200 is the largest unit of the Israeli army and covers the entire spectrum of intelligence services; its closest equivalent is the American NSA], from which most founders of cybersecurity and surveillance companies have served. Gordon explains that many projects that start within the army are released in order to be developed by the private sector, and it is then common for them to be offered back to the army. “When the army gives its approval, then the project enters what I would call a laboratory,” he explains.

The “laboratory,” that is, the testing ground for security and surveillance, is, according to Gordon, the battlefields where the Israeli army operates, including the occupied Palestinian territories. This is a finding that has also been made by other researchers, such as Leila Stockmarr, who in a 2016 study argued that a crucial aspect of Israel’s advanced military and police capabilities is how “new technologies are developed and tested in comprehensive population control situations, such as in the Gaza Strip.”

In this model, the private security and surveillance sector is treated as a testing ground for the military and vice versa. The military can test new products for its own needs in areas such as the West Bank, the Gaza Strip and eastern Jerusalem. And through contracts with the military, companies that develop cybersecurity or surveillance programs can optimize their products through field experience, before going out to foreign markets. (…)

a state of initial chaos

And this brings us back to NSO Group and Pegasus. A previous year investigation by Citizen Lab found evidence of infection by the virus in 45 countries, including the UAE, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Lebanon, and the Palestinian Territories. This was followed by a second investigation, which concluded that Omar Abdulaziz, a Saudi activist and permanent Canadian resident, had been infected by the Pegasus spyware.

Citizen Lab’s research was published just one day before Jamal Khashoggi was murdered. Abdulaziz, a friend and collaborator of Khashoggi, intended to file a lawsuit claiming that communications between himself and Khashoggi were under surveillance by the Saudis using software from NSO Group. The company denied any involvement, with its co-founder Shalev Hulio stating in the Israeli newspaper Yedioth Ahronoth that Khashoggi was not targeted “by any product or technology of NSO.” However, at the same time, the Washington Post, citing two senior American intelligence officials, reported that Saudi Arabia had indeed purchased software from NSO through a Luxembourg company named Q Cyber Technologies.

As cybersecurity evolves into a massive business field and regional dynamics are reshaped intensively, the new front of cyber espionage is simultaneously developing as a major Israeli export product. As Israel’s ties with the Gulf kingdoms are no longer particularly hidden, how it will manage the lobbying of its developed private cybersecurity sector may prove to be an issue of crucial significance for the future political situation in the Middle East.

what does Israel’s strike against Hamas hackers mean for cyber warfare

This weekend [early June 2019], violence in Gaza escalated to levels not seen since 2014, with 25 Palestinians and four Israelis killed. (…) But for cyberwar experts, one particular event was especially significant: Israeli forces claimed they bombed and partially destroyed a building in Gaza because it was allegedly the base of an active Hamas hacker group.

This attack appears to be the first real example of a physical attack in response to digital offensive actions—a further development of the so-called “hybrid warfare.” It is a defining moment, though analysts warn it should be examined within the context of the conflict in Palestine, rather than as a global first or general warning for the future.

What happened?

It’s a very good question, which however has not yet found clear answers. The Israeli army, in a tweet on Sunday, stated that “we prevented an attempted Hamas cyber-attack against Israeli targets. As a follow-up to our successful cyber defense, we targeted a building where Hamas cyber agents were operating. The HamasCyberHQ.exe was deleted.” But the IDF has not provided any details regarding the nature of the alleged cyberattack, and it is unclear from current announcements why Israel chose to proceed with the strike, while at the same time claiming it had already prevented the attack.

State-sponsored cyberattacks and conventional warfare have already been slowly but steadily converging for two decades, and researchers in both information security and warfare support that it is only a matter of time before a state launches a conventional attack against enemy hackers. “When I participated in the first Cyber Command, in April 1999, we discussed that something like this would be extremely serious if it were to happen,” says Jason Healey, former official in George W. Bush’s administration and current researcher on cyber conflict issues at Columbia University. “I wouldn’t say we had plans, but we thought about it thoroughly.” The U.S. has officially declared since 2011 its right to respond with military means in case it suffers a cyberattack.

Has something similar ever happened before?

Basically no, but with some reservations. The role of destructive cyberattacks in a total war has expanded over the past few years. Russian-backed hackers have caused sabotage on critical infrastructure during wars, such as in Georgia and more so in Ukraine. A more relevant example is a U.S. airstrike in 2015 targeting an Islamic State hacker, Junaid Hussain. But that attack was planned over months, in contrast to the Israeli attack which occurred in immediate, real time. And Hussain had been targeted not simply as a hacker, but as a key figure in ISIS’s recruitment networks.

What complications arise from this particular incident?

There are currently two approaches regarding the interpretation of the IDF attack. Some consider it a turning point in the evolution of hybrid warfare, which potentially sets a dangerous precedent, making hackers, even those engaged in offensive actions, legitimate targets of physical retaliation.

«Hackers are unarmed,» says Jake Williams, a former member of the NSA’s elite hacker team Tailored Access Operations [National Security Agency: the American national security agency]. «They are not in a position to defend themselves. Of course, in battles, it is common for even fighters who cannot defend themselves to be targets of airstrikes. I think, however, that the crucial difference is that these fighters can cause loss of life and constitute a clear threat, unlike hackers, who do not pose such a risk. They are support personnel behind the lines. If ISIS strikes our forces stationed in Iraq, the world will understand that they were clearly in the line of fire. But if ISIS strikes soldiers waiting in line to get paid at Fort Gordon, back in the US, they are a less legitimate target, even though they are combat troops.»

Williams notes that hackers potentially have the ability to cause harm in the real world by hacking critical infrastructure. But he warns that just because hackers manage to gain access to a system or even appear to be organizing an attack, this does not necessarily mean the attack will occur. They may simply be breaching a system for surveillance or information-gathering purposes.

On the other hand, war researchers have a different perspective and note that this specific incident occurred within the context of a larger-scale attack, which had nothing to do with what is happening in the cyber domain.

«The fact that the IDF made this stupid joke about the ‘Cyber HQ’ is certainly the most noteworthy, because it shows they can make ruthless jokes while killing people» says Thomas Rid, professor of strategic studies at Johns Hopkins University. «But here we are not dealing with cyber warfare and what happened had nothing to do with cyber deterrence. It appears that the building was used by Hamas intelligence services, so it was a legitimate target for Israel».

Is some kind of precedent being created?

Regardless of their views on the bombings in Gaza, many analysts agree that incidents of physical, violent reprisals against hackers are now inevitable, as modern warfare continues to evolve. But the actions of the IDF do not seem to set a strong precedent, especially for countries that are not actively at war.

«The most important thing in this case is that there was already an armed conflict underway», says Lukasz Olejnik, an independent cybersecurity consultant who collaborates with the University of Oxford. «It is a unprecedented incident that will prove to be of great significance in the history of cyber conflicts. But it is not a boundary crossing. The fact that fighters can be targeted is not exactly a surprise. And as more and more states treat cyberspace as a battlefield, we would reach this point sooner or later».

Nevertheless, state-organized cyberattacks occur constantly, without missiles entering the game. Russia has carried them out in Ukraine and elsewhere. Israel and the US had developed the destructive malware stuxnet to sabotage Iran’s nuclear program. And China is involved in long espionage campaigns aimed at stealing intellectual property. Until now, states that are not at war have dealt with such actions through diplomacy, sanctions and accusations, without sharpening oppositions to the point of normal military actions.

Analysts also note that it is likely the line, after which hackers constitute a target of physical attacks, has been crossed long ago by some state that had less inclination to boast about it. “If we could examine the whole story, would we conclude that Israel’s attack was really the first?” Healey asks regarding the IDF’s strike on Hamas. “Perhaps we would discover that the US or some other country has already carried out some physical attack, but certainly this was the first time such an attack was advertised. What we conclude is that when you are in attack against another country, more and more targets will end up being considered legitimate. When you are at war, you are at war.”