In every historical era, there is a core set of ideas through which a society understands itself and which outline its worldview. Ideas that in other times would seem bizarre or even unthinkable “suddenly” acquire the status of the self-evident, and individuals appear to swim within them like fish in water. For the societies of the hypermature capitalism of recent decades, one such defining element of their worldview is the notion that “reality is fluid,” that “there is not one single reality but only interpretations of reality,” and ultimately that “everyone has their own reality, their own private universe.” It is now assumed that such a repudiation of a single reality has something progressive and liberating about it, that it is the result of tolerance. If everyone has the right to build their own personal universe and a personal interpretation of reality, then automatically it follows that no one is allowed to impose a different interpretation on them. And thus, the denial of reality acquires an almost “resistant” and “revolutionary” hue. In our view, this is an ideology – in the Marxist sense of the term – distinctly postmodern, with its own genealogy. And this genealogy can be traced.

Of course, the relationship of every society with reality has never been unambiguous. The construction of alternative realities to the tangible and immediate reality of the senses has a tremendous historical depth. Religions were an archetypal mechanism for splitting reality into multiple levels. A basic motif of shamanic rituals (perhaps the oldest religious practice) is the ascent and descent of the shaman into different worlds, into spiritual worlds beyond this sensible reality. Similarly, the great monotheistic religions (and not only) would be built upon the metaphysical assumption of the distinction between two realities, one empirical and one higher spiritual. However, there is a crucial difference between the multiple realities of religion and the alternative realities of modern societies. Religious realities were socially binding. The experience of the shaman and the spiritual realm of Christianity did not allow multiple interpretations – with the significant distinction that the interpretation of the shamanic experience was multiply mediated by the collective memories and knowledge of the tribe, while the higher spiritual realities of monotheistic religions were dogmas that were often imposed through ruthless violence.

The above brief observations are already sufficient to demonstrate the enormous distance that can separate different societies in terms of the relationship they “choose” to build with reality and the external world. Such a thing, of course, should not be surprising if one takes into account the extent to which these social formations differ in other aspects and structures as well. A nomadic tribe centered around shamanic rituals, a Christian kingdom of medieval Europe, and a Western industrial state in the postmodern era of advanced capitalism differ so radically in the levels of their economic relations, political institutions, and historical trajectories that it would be rather unlikely for them not to differ equally in their ideological constructions as well. The issue, however, is not simply about noting the existence of such differences—an observation that is more or less self-evident. What is important is identifying those factors which, under specific historical and social conditions, bring a particular ideological construction to the foreground while condemning others to obscurity or even ridicule (today, supporting the idea that reality is one, unified, and coherent is considered rather outdated and “naive”). Such fluctuations in the density of ideological constructs, which bring some to the surface while pulling others into the depths of the social fluid, have little to do with the “free will” of individual persons. Citizens of today’s Western societies complacently believe that their adherence to the ideology of multiple realities constitutes a personal choice, naturally attributed to the high levels of sensitivity and cultivation they have attained, without considering that this may have been imposed on them from an early age (just as their particular cultivation and corresponding sensitive points have been imposed upon them). The ideological frameworks of each society, as well as the ways in which these change form, are certainly far removed from the fantasies of its members; rather, they emerge as results of long-term historical processes and through conflicts of tectonic scale. The same, of course, applies to the ideology of multiple realities. Although it appeared and spread widely for the first time in the second half of the 20th century, this emergence was neither abrupt nor disconnected from earlier, similar ideas that had already gained popularity from the first half of the century or even earlier.

From a broader historical perspective, therefore, this particular perception can be placed within the spectrum of possible responses to an age-old philosophical question: that concerning the nature of the external world and the way human subjects perceive this world. Precisely because the external world sometimes appears to lose the firm stability usually attributed to it (as is characteristic in cases of dreams, hallucinations, or conflicting testimonies about the same event), for this reason the nature of the world itself can initially be posed as a philosophical problem; and with the same move, consciousness (or the soul/spirit, using more “outdated” terminology) can acquire a central role in philosophical discussions. Naturally, it is not coincidental that the problem of the relationships between consciousness and the external world constitutes a permanent motif in philosophical discussions since antiquity.1 The reason, in our opinion, lies in the very nature of the problem-question: it is fundamentally a metaphysical issue, where the term “metaphysical” is initially intended without religious connotations and without any derogatory disposition. The term is used with a more Kantian intention, aiming to highlight the boundary character of the question which, by its very nature, exceeds human capabilities to handle it rationally, based solely on epistemological criteria. It is indicative, moreover, that throughout the history of ideas the most fantastic answers have been constructed for this question, to which, however, plausibility was never lacking.2 If epistemological criteria are insufficient, however, it follows that any philosophical (or even religious, artistic, etc.) constructions attempting to deal with this issue must draw vitality from other sources. And these can only be of a social, political, moral, or even aesthetic nature. The interest here is that, precisely due to its metaphysical character, the question of the external world not only does not lose value, but is upgraded, albeit at a different level; since it functions as a capacitor of collective struggles and hopes, it becomes an ideal field for sociological interpretations. What struggles and what hopes, then, lie behind the popularity of today’s answer to the question of the external world, that of multiple realities?

idealism and materialism

If one wishes to draw up a typology of the answers that have been given throughout the history of philosophy to the question concerning the nature of the world, one could arrange them (even if somewhat broadly) along two basic axes. The first axis concerns the “what,” the “essence” of the external world, the material from which it is supposedly constructed. The two major lines of thought that have traditionally been rivals in claiming the “essence” of the world fall under the (broad, to be sure) names of idealism and materialism. Although the concepts of “idea” and “matter” have undergone significant conceptual shifts over the course of 25 centuries of philosophy (to remain only in the West), it seems that some of their characteristics have remained sufficiently stable for the derived terms “idealism” and “materialism” to have orientational utility as a first compass.3

The “idea” is typically associated with what is usually rendered in terms of spirit, soul, and thought; “matter,” on the other hand, refers to what relates to the body and immediate sensory impressions. Thus, both the elective affinity of idealism with intellectualism and the consistent preference of materialist philosophies for empiricism become understandable. For the latter, the world is fundamentally material, as is somewhat—or very—perceptible by the senses, with any immaterial or invisible substances considered merely as secondary derivatives. For idealist currents, priority is naturally reversed to be given to spirit, which is called upon to act as the first principle of the world. Around the two fundamental keys of idealism and materialism, countless variations of the piece called “the essence of the world” have been played, without any philosophy having fully transcended this duality. As for the second axis, it is dominated by another emblematic duality in philosophy, that between dualism and monism. Dualist conceptions introduce a chasm into the world, dividing it into two different levels of reality, one of which is usually accorded some ontological (or even moral) superiority. Monism, on the other hand, tends toward a conception of the world that sees it as consisting of one and only one substance and governed by a single, unified logic, without ontological divisions that imply corresponding value distinctions. This duality also has a steady presence in the history of Western philosophy, from which impressive intellectual constructs have occasionally sprouted. Within the history of ideas, however, the above distinctions between idealism and materialism on the one hand, and dualism and monism on the other, have not been applied with absolute consistency and rigor. In fact, philosophies that were absolutely aligned on only one side of each of these two dualities have rarely existed (e.g., extreme dualist systems that cleave the world into two unbridgeable realities—Descartes came quite close, but even he retained a point of connection). It is important, however, to identify at each historical moment which side is being prioritized and for what reasons this occurs.

Ancient Greek thought is a typical example of a snapshot from the history of philosophy which, despite its diversity, never developed intense dualistic tendencies, yet without completely freeing itself from them.4 A characteristic case of an essentially monistic philosophy that nevertheless has some mild deviations toward dualism is Aristotle. According to Aristotle, the fundamental principles of the world are two: matter, which constitutes something like a primary, formless and shapeless substrate, and form, which, as a more active principle, shapes the formless matter. This scheme appears dualistic at first glance; and indeed it is, but to a much milder degree compared to more traditional dualisms, such as those of Plato and Descartes. The concept of form does indeed seem to have something immaterial, especially since, through multiple levels, it ultimately leads to Aristotle’s divine Intellect. However, it is not connected to any kind of will or soul, thus functioning more as a cosmic force (much like in modern physics there are fields and forces that are invisible, yet for that reason alone are not considered “immaterial” or “spiritual”). The result was naturally the absence of any longing for other worlds to which an immortal, individual soul could migrate, as occurred in later Christian times. Even in their most popular mythological constructions, the other world of the ancient Greeks took the form of a gloomy underworld, a Hades in which it is not worth being, even as a king. The world that has value is the immediate world of the senses and not “higher” realities that remain forever beyond reach.

The desire for other worlds may have been essentially non-existent in the ancient world, yet something more than existent was the passion for discovering multiple interpretations of the one world of the senses; a passion that found its most characteristic expression in the current of sophistry. If there is a complex of ideas within the history of philosophy that has close affinities with the postmodern ideology of multiple realities, it is this current—sophistry. The basic point of convergence between ancient sophistry and postmodern relativism lies in the rejection, by both, of the concept of a single, unique, and time-invariant truth. The sophists were probably the first philosophical current to give us a prospective understanding of truth: the way each person perceives what holds as true or even as good ultimately depends on their social position, their mental and physical condition, and even their interests. There is no privileged, Archimedean point from which one can survey reality as a whole and pronounce on truth in a way that is universally binding for all people. This relativization of truth was sometimes expressed in relatively mild tones, as a critique of traditional, mythological, and religious ways of thinking, while at other times in more extreme, aggressive emphases, as an outright rejection even of the slightest notion of truth and justice, identifying moral good with the right of the strong (e.g., as Thrasymachus does in Plato’s Republic).

There are, however, some critically important differences between ancient sophistry and the contemporary potpourri of postmodernism. In its milder versions, sophistry understood itself as a quasi-therapeutic practice with potentially universal resonance. By placing at the center of reflection the conflict between “nature” and “civilization,” with all the oppression that the former suffers from the latter, it seems at times to imply that a return to a more “natural” morality is desirable, where human beings would have themselves as the measure of judgment and not mythological fantasies.5 Clearly, such a moral and political stance has little in common with the spineless and flabby tolerance of postmodern liberalism that accepts everything… until, of course, the bosses decide to tighten the reins on their otherwise tolerant subordinates (and then they suddenly discover, for example, that seeing Muslim women wearing headscarves in the street deeply offends them). Even in its most extreme versions, sophistry was never merely a philosophical theory, a painless and harmless topic suitable for casual discussions over cheese and pear, or contests of pseudo-philosophy. It was absolutely tied to a combative stance within a demanding public sphere where the gleam of arguments competed with that of weapons. The sophists taught how to persuade a public audience through reason alone on absolutely burning political issues (the Sicilian expedition, which marked the beginning of Athens’ decline, was decided in this way). Consequently, choosing one interpretation over others (equally valid, according to the sophists) was often a matter of literal life and death, certainly not a trained reflex for consuming spectacular realities in front of a screen. The reason, of course, was not some “free spirit” that the ancient Athenians supposedly possessed “innately.” Sophistry was born through the institution of public dialogue, which in turn originated from the social conflicts of ancient Athens. In fact, it was the balance point that emerged from the conflict between an aristocratic class and a destitute rural mass; since neither of these classes could impose itself by force, public dialogue arose as the medium that could defuse tensions.6 Gradually, rhetoric (the subject taught by the sophists) developed as a technique of persuasion that the aristocratic class – the only one that could afford to purchase the sophists’ services – could employ against a crowd it could not control by other means; sophistry’s teaching on the relativity of truth became the ideological defensive line of a class that was unable to impose its own truth. In any case, it is important to emphasize that sophistry questioned truth (that is, the interpretation of reality), but not sensory reality itself.7

So far, we have avoided references to the Platonic teaching. Without any disposition to undervalue the significance and greatness of Plato, our sense is that the core of his ideas, especially his ontology, fits more naturally into later centuries, and that in his time he was rather the exception than the rule. It is not coincidental, moreover, that Christianity in the Middle Ages made systematic use of Platonic ontology, while it turned mainly to Aristotle for its logical inquiries. Plato, then, was the pioneer of the longing for other worlds, which also serves as the firm backdrop for every Christian cosmology. The truth is that the Platonic dualism remained largely noetic. The Platonic Ideas dwell in a higher, mental reality, with sensible objects being poor copies of the Ideas, cheap and unskilled replicas of them; yet they are Ideas with a geometric order and serenity that one reaches through thought, without heart’s exaltations and emotional spasms. A significant step away from this cold noetic dominance would be made by Neoplatonism in the first centuries AD, under the strong influence of Eastern religions. Although philosophically less dualistic than Platonism—since the entire world is structured in a system of emanations from the primal One, which are consubstantial with it—it is governed by such an aversion to sensible things, and the description of union with the One is expressed in terms of mystical rapture, so much so that it can rightly be considered as taking yet another step closer to Christianity. Christianity would ultimately complete the process of devaluing sensory reality, treating nature as the quintessential domain of chance, unworthy of interest except insofar as it poses obstacles on the path toward individual salvation. If one takes into account the social and political conditions within which the proto-Christian philosophical movements and Christianity itself developed, it becomes understandable why a stance such as that of the sophists could not survive, but was doomed to be replaced by intensely dualistic worldviews.8 Within the framework of a multicultural empire that had managed to continuously expand through wars of conquest, a degree of syncretism (such as that which borrowed Eastern elements into Neoplatonism) was rather to be expected. However, this syncretism could not ascend to a Roman stance like that of the sophists, as it lacked its essential support: public dialogue as the fundamental institution of political life. At the same time, since for the overwhelming majority of the empire’s subjects the ability to control political and social developments had been minimized, the dominant ideologies withdrew their points of connection with external (social) reality and folded inward into increasingly mystical constructions, longing to find salvation in transcendent worlds. Sensory reality had not disappeared; it had been devalued as unworthy of interest in favor of another, immaterial reality, beyond the bonds of the senses.

Lighting – and beyond

Christian dualism, with its consequent devaluation of nature, would remain dominant in Europe for nearly ten centuries, essentially until the Renaissance.9 In the centuries that intervened between the Renaissance and the Enlightenment, certain developments would emerge that radically transformed the ideological–philosophical frameworks of European societies: the gradual development of mathematical physics, the discovery of new continents (and peoples) through overseas voyages, and the emergence of some primitive forms of capitalist organization of production and trade, accompanied by the gradual concentration of political power in the hands of monarchs, which in turn set in motion the weakening of the nobility and the eventual subjugation of unified geographical areas to the power of nation-states (and no longer fragmented kingdoms). Naturally, these were developments that proceeded at very different speeds in different countries (e.g., in England they were completed relatively quickly, while Germany and Italy had to wait until the end of the 19th century), but the general pattern is sufficient for our purposes in this article. Scholastic philosophy, which Christian monasteries had cultivated with such zeal for centuries, began to seem quite inadequate in responding to the demands of the new social formations. Outspoken attacks against religion only became common from the Enlightenment onward, but behind the statements of religious propriety made by the thinkers who prepared the way for the Enlightenment, a common thread can be clearly discerned. The tortuous paths and awkward, rope-like arguments of scholasticism, with its insistence on certain intangible and rigid Ideas, no longer had any “usefulness.” Philosophy had to become “useful,” to be applicable to the real world, to pave the way toward a dialogue with nature.10 The result was the rehabilitation of nature as an autonomous field, which not only deserved philosophical investigation but should henceforth constitute the primary domain of scientific inquiry. For the goal was certainly not a detached knowledge, which, moreover, scholasticism had offered abundantly, but rather the conquest of nature, its domination, and its subordination to human purposes.

To achieve such a thing, initially a host of skeptical and relativistic arguments were mobilized which, even if indirectly, attacked the religious worldview. Montaigne (16th century) is a typical example of a thinker who used such arguments in his attempt to sow doubts regarding the superiority of Christian ideals, by comparing the behaviors of his own Christians with those of the “uncivilized” peoples from other continents. From this perspective, one can speak of a temporary revival of sophistry in its milder versions, which, without reaching extremes and without becoming dominant, nonetheless runs like an underground current through the entire modern philosophy. However, Enlightenment optimism never permitted the complete fragmentation of reality; the human spirit could and should grasp this reality, even if such a task required arduous effort. The grand philosophical systems of the 18th and 19th centuries, such as those of Kant and (even more so) Hegel, overflow with the conviction that the world is governed by logic and that knowledge can be arranged into an orderly whole, even if the price for such knowledge includes entire centuries of bloodshed, violence, and oppression, as in Hegel’s theodicy—the assertion by Joyce that “history is a nightmare from which I cannot awake” would have been unthinkable for Hegel. The 19th century was the century of the triumph of the bourgeois class and, as such, had to repel any centrifugal tendencies toward a fragmentation of reality. Yet for the same reason, it inherited one of the fundamental contradictions of the bourgeois class: the split within the bourgeois individual between his role as a citizen of a state and his role as a private individual who must look after his own interest within an extremely competitive environment. Such a permanent sense of irreconcilable opposition to (social) reality nourished and sustained the continuing presence of dualism in the philosophical systems of modernity. This “dualism” could be quite mild, as in the case of Kant, or almost absent, as in the case of Hegel. Yet it always began by taking as given the epistemological (or even ontological) primacy of inner experience, of the self versus the external world—something observable not only in German idealism but even in Locke’s empiricism.11

The first cracks in the Enlightenment edifice would only become apparent toward the end of the 19th century. At its close, the 19th century left behind as legacy the epic of capitalist and scientific spirit, but with a thorn in its side: continuous economic crises and political revolutions. The sense of suffocation caused by the traditional norms of the triumphant bourgeois class was now widespread. During the famous fin de siècle, spirits would begin to move toward the constellation of decadence, distancing themselves from the great philosophers—architects of the past—and moving toward the damned underminers of certainties and traditional values, thus entering the zodiac of sensualism and relativism. Baudelaire, Rimbaud, Wilde, and Nietzsche were only a few of the new heroes who marked that fragile era. The magma from the underground current of relativism found its way back to the surface, and reality once again became a field of contention, losing its coherence.

The first half of the 20th century managed to “respond” to the challenges of decadence with a dual movement. On the one hand, it set in motion the machines of both mass production and mass consumption; on the other hand, it appropriated the challenges of the decadents, but in a way that would be suitable to the demands of mass societies: sensuality became an advertising billboard and relativism a liberalization of (consumer) morals. The reaction of philosophy appears to have been rather defensive in this first phase (and we say this without a dismissive attitude). Husserlian phenomenology attempted to discover the purity of the world (and perception), going back behind the (scientific or other) interpretations of it – from this perspective, it incorporated the challenge of relativism, but with the purpose of transcending it. More moralistic, Heidegger devoted himself to searching for a certain lost authenticity amid the chaos of mass societies.12 In any case, however, philosophy had begun to lose its luster and “usefulness,” especially given the central role it would gradually play in shaping ideology through the development of the mass culture industry.

On the contrary, the positive sciences evolved in synchrony with the spirit of the times, also claiming their share in constructing stars for consumption. The theory of relativity for gravity and quantum mechanics for atomic phenomena were both built upon the common relativistic assumptions of the non-existence of absolute reference points and the dependence of phenomena on the observer. Less known but similar were the developments in mathematics. In the attempt to find solid foundations for mathematics (Hilbert’s program), mathematicians eventually came to the conception of the purely abstract character of mathematics, which does not (need to) have any relation to concrete, sensory reality, except perhaps symptomatically. The mathematician is free to create formal worlds and realities as he sees fit. Through this endeavor, the new sciences of computer science and cybernetics eventually emerged. Setting aside the earlier obsession of mathematics with continuous quantities and functions, they placed discrete (digital) quantities at the center, which become objects of manipulation by algorithms, that is, by sequences of well-defined and utterly elementary steps.13 The process of dividing mathematical entities into small and interchangeable elements thus reveals structural correspondences with the ongoing individuation of Western societies.

It is interesting to observe the evolution of the relationship between the societies of the first half of the 20th century and reality from yet another perspective: through the sensitive seismograph of literature. A fundamental literary technique for the early great novelists, such as Stendhal and Balzac, was naturally writing from the perspective of the omniscient author. Perhaps it is unnecessary to point this out, but it is significant for what follows. Such a narrative stance is only possible if the author holds a belief both in the existence of a reality and in his own ability to capture it on paper. Reality may be labyrinthine (and Balzac’s ambition to create a panorama of French society was accordingly abyssal), but it exists, it is out there, waiting for the author to grasp it. For the literary modernism of the early 20th century, such a stance of depicting reality as it is would seem naive and childish. Not because such a reality does not exist, but because the interior monologue of Joyce, the poetic, introspective prose of Broch, and the finely wrought psychological visions of Proust indicate a shift in attention toward what they themselves consider to have literary value: the transformation of reality within the subject. Their aim is to use the prism of literature to refract reality into rays of different hues, as these illuminate (or cast shadows on) the psychological journeys of their characters. In a sense, these are “anti-realist” techniques which, paradoxically, often lead to an even more penetrating reading of (a) reality. Moving in a different direction, Kafka, at first glance, remains within the framework of describing external reality, without engaging in extensive psychological analyses. Yet this is not the logic of the omniscient author. Both the reader, and one suspects the author himself, stand before a reality that exceeds their capacity to understand and make sense of it. Individual segments of this reality may follow an iron logic (e.g., in The Metamorphosis, the reader need only make the initial leap of faith and accept that Gregor Samsa has been transformed into an insect, after which the plot unfolds with fairly convincing logic), but the overall structure in Kafka’s works resembles a building whose parts are constructed from the hardest concrete, even as the joints appear to be made of clay. Reality still exists, yet the absurd and relentless logic have become locked in a nightmarish dance with no prospect of escape. By the time we reach Beckett, reality has been fully disintegrated into countless fragments that no longer even maintain a semblance of logic. Reality has not been dissolved; it remains necessary as the stable backdrop that renders its own fragmentation all the more convincing. This progressive disintegration of reality in the literary works of the first half of the 20th century was, of course, not unrelated to the evolution of the societies that gave birth to them. It can easily be read as a cry of despair in the face of the Leviathan of state bureaucracy and the Behemoth of the mass production factory, which were then beginning to spread their tentacles in all their monstrous “grandeur.” And from this perspective, these are indeed invaluable works.

The Rise of Subjectivism

Entering now into the second half of the 20th century, the concept of a single reality has by now suffered serious blows, but still retains some minimal elements of coherence. The observer in quantum mechanics may influence the phenomenon being observed, but from the moment of observation onward, once the wave function collapses, reality condenses and solidifies. Quantum mechanics can be read more as an agnostic rather than a pluralistic stance toward reality. Relativity, on the other hand, may eliminate absolute reference points in space-time, but with appropriate mathematical transformations, it is possible to provide a universally binding description of reality. In philosophy, the interesting experiment of convergence between phenomenology and Marxism will give a new breath to dialectics, which by its very nature constitutes a dynamic conception of reality, without denying it. Ultimately, however, the experiment will prove rather short-lived, enjoying only temporary popularity. In any case, the relativization of reality was still expressed mainly at the level of multiple interpretations, assuming that behind these interpretations there still exists a reality, at least at the sensory level.

The breakthrough into the skies of alternative realities would ultimately become feasible only after the end of the war and more specifically from the 1960s onward. There is a thread connecting the shamanism we mentioned at the beginning of the article with the societies of that decade: the revival of religious zeal in the form of the New Age movement. Within the context of increased interest in religions, their practices, and generally in different ways of perceiving reality, significant work was undoubtedly done, mainly in anthropological and psychotherapeutic directions, especially to the extent that such quests were linked with the social demands of the era – let us not forget that anti-psychiatry was a product – a creature of that turbulent time. Once the dust settled from those upheavals, however, the search for alternative realities veered toward increasingly spiritualist paths, eventually leading into the embrace of the neoliberalism of the 1980s. A development that, of course, was by no means coincidental. There was a conscious top-down effort to reorganize both production – with the introduction of new networking and robotics technologies – and ideology in such a way as to “creatively” absorb rather than negate the protests of previous decades. Greater “autonomy” (essentially imaginary) in production spaces, greater flexibility, increased consumption (even through borrowing, since real wages remained stagnant), and of course an unprecedented emphasis on the individual, with their unlimited rights to self-realization. The demand for another reality thus transformed into a call for tolerance toward alternative realities, in sync with the process of extreme individualization that neoliberalism would set in motion.

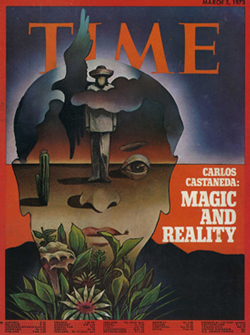

As expected, the shift towards relativizing reality found both its philosophical expression, with the emergence of postmodern theories and their protest against the “dictatorship of Reason,” and its social reflection through the establishment of identity politics as the political correctness of our time, where everyone is what they declare. Equally important, however, is the following. With the expansion of the mass culture industry, initially through television and subsequently through digital media (e.g., video games or more recently through virtual and augmented reality applications), the ideology of multiple realities has now moved from the level of interpretations to the level of the senses. It is not only that there are many realities, but it is also possible to construct alternative realities at will. Through this process of inflationary devaluation of reality, psychedelics were eventually replaced by hard drugs (indeed, supplied by para-state actors via organized crime), new age was academically and philosophically expressed as the postmodern end of grand narratives in favor of “local and ephemeral resistances,” and Don Juan of Castaneda became a caricature by the spectacle industry in the form of Anthony Quinn in The Magus—a industry that was now able to offer ready-made realities for consumption.

And so, in a way, the cycle of commodifying the senses began. Reality itself became a commodity, with versions that can be bought and sold to match the lifestyle choices of citizens in Western societies; its exchange value becomes even greater if it carries a hint of “rebelliousness.” And while insisting that reality can be interpreted in ways different from those imposed by the current authority once held significant weight, today’s zealous or uncritical adherence to the ideology of multiple realities is rather a sign of willing servitude. It is once again the same power, which through its dialectical transformations has reached such a point of refinement that it creates the illusion of denying itself. Such a denial of reality offers easy, cost-free, and sometimes even pleasurable escapes—it repeats, after all, the old recipe of every traditional religion. But this movement, at the end of its path, affirms precisely what it claims to deny: an unbearable reality with the force of a black hole, which devours in its passage whichever alternative worlds the citizens of Western societies carelessly construct in order to feel a virtual security and occasionally receive their corresponding adrenaline fixes, amusing themselves in their boredom.

Separatrix

- The philosophical fashion of the 20th and 21st centuries does not feel very comfortable with such “primordial” philosophical questions, perhaps also due to an instinctive aversion to anything that seems to point to some kind of “substantialism” (if such questions hover unbidden in the philosophical sky, as constant sources of anguish and awe for humanity, then this perhaps indicates that certain aspects of humanity have remained unchanged for several thousand years). On the other hand, such is the zeal of contemporary philosophical movements to cast into the fire all previous philosophy under the accusation that it has been “metaphysical” that they have little sympathy left for earlier currents (Heidegger and Derrida are typical examples of philosophers with such excessive ambitions). In any case, however, since such primordial questions do exist, for better or worse, and since it is good to be able to view them from a historical perspective (so as to avoid being easily impressed by the various self-proclaimed saviors of philosophy), we refer to the captivating book by Heinz Heimsoeth, “The Six Great Questions of Western Metaphysics and the Roots of Modern Philosophy,” P.E.K. Publications, translated by M. Papavassiliou. ↩︎

- Berkeley’s idealistic philosophy constitutes such an example, which had been said to be the most extreme form of madness, yet one that cannot be refuted by logical arguments. ↩︎

- When and why exactly the gap between “spirit” and “matter” emerged in human thought is an extremely interesting question, which however we will not delve into. ↩︎

- We will avoid references to the pre-Socratics, for whom monistic elements were even more pronounced. Both for reasons of economy, and because they seem to stray from the classic spirit-matter duality. ↩︎

- This tendency towards a return to a more “natural” morality is more intense and persistent mainly among the Cynics. One can find collected fragments of both the Sophists and the Cynics in two scholarly books, translated by N. Skouteropoulos, published by Gnosi, with the titles “Ancient Sophistic” and “The Ancient Cynics”. ↩︎

- See “History of Ancient Philosophy”, M. Vegetti, trans. G. Dimitrakopoulos, ed. Traulos. ↩︎

- Something similar happened with the skeptics, who however end up in an agnosticism and not in a proliferation of realities. ↩︎

- For reasons of economy, we have not referred at all to gnosticism, which however constitutes a source of even more extreme examples of dualism. See the book by Hans Jonas “The gnostic religion: the message of the alien God and the beginnings of Christianity”, ed. Beacon Press. ↩︎

- Here we overlook some more heretical thinkers, such as those of German mysticism (e.g., Meister Eckhart, Nicholas of Cusa), with their strong monistic elements. Although they are of exceptional interest from a philosophical point of view, their influence was rather limited in their time (at least in relation to the dominant currents), while they reappeared several centuries later, e.g., as influences on Hegel (even there, in a not directly obvious way). For details, see also again Heimsoeth’s book. ↩︎

- The rejection of scholasticism and the demand for a useful philosophy had spread so much that they can even be found in the otherwise idealist Berkeley (see his book “Principles of human knowledge”). For a more general overview that emphasizes the anti-intellectual tendencies of the Enlightenment, see the book by P. Kondylis, “The European Enlightenment,” published by Themelio. ↩︎

- For more details on this point, see Cyborg, vol. 8, the Turing test: notes on a genealogy of “intelligence”. ↩︎

- Although Heidegger insisted that the search for this authenticity takes place at a purely philosophical level and has nothing to do with ethics, as has been correctly pointed out (e.g., by Sartre in “Being and Nothingness”), it is almost impossible not to attribute some ethical hue to the relevant discussions in “Being and Time.” ↩︎

Evolution that caused the monthly mathematical magazine of earlier cut, which accused the new mathematics of resembling more and more a factory where you put pigs on one side and sausages come out on the other. If we remember correctly, this analogy belongs to Poincaré. We are not sure that in this way he managed to offend his opponent colleagues. Anyway, some of them used the analogy of the worker in front of the production line themselves to describe the algorithmic process.

↩︎