September 19, 2019: An attack by American drones in the Afghan province of Nangarhar resulted in the mass murder of 30 farm workers and the injury of another 40, while they were resting after their work. The alleged target of the operation was an Islamic State “safe house”.

September 25, 2019: An attack by Afghan government forces in the province of Helmand, with the support of the American army, against a building that was allegedly housing a Taliban armed “safe house”. The outcome was the bloodbath of a wedding party and the mass murder of 40 civilians.

December 1, 2019: In the Afghan province of Khost, an American drone struck a vehicle, killing all five passengers. Among them was a woman who had just given birth and was being transported to the hospital. The American army claimed that the attack targeted three Taliban members and declared ignorance about the civilians.

January 8, 2020: An attack by American drones in the province of Herat resulted in the murder of 10 civilians and the injury of more than 50. According to the American army’s statement, the attack targeted a Taliban checkpoint, was “successful”, and reports of civilian casualties “will be investigated”.

The aforementioned events, recent and indicative, are drawn from the extensive and ever-expanding list of military actions by the American army that result in bloodbaths with civilian casualties. Their common characteristic is not merely that they involve cold-blooded mass killings of civilians, but that they are operations decided, planned, and executed with the mediation of cutting-edge digital technologies. They are supposedly organized based on highly accurate information drawn from massive databases and processed by “smart” algorithms, in order to achieve surgical precision and maximum effectiveness. At least that is what the relevant rhetoric claims, a rhetoric that remains unshaken despite the hundreds of civilian deaths; unless, of course, that is precisely the goal.

The technological fetishism of the “most powerful” war machine has now reached such a point as to claim omniscience or to believe it possesses it. “We know everything about everyone”: this could be a maxim of the most pathetic theology or totalitarianism, but today it encapsulates the ideology of the American army’s modus operandi. It doesn’t matter whether such a claim is or can be true; it suffices as a pretense to produce utterly tangible, practical outcomes, such as a massacre of civilians in some village in Central Asia. When the drone operator sits in his comfortable gaming chair and directs a blind instrument of death, he is merely a biological intermediary executing the technological will of an algorithm from a database. This is how war is conducted today, like a system of inputs and outputs within a digitized universe. On one side, information flows in—analyzed, deconstructed, reconstructed, and locked onto a target—and on the other, raw, blind bestiality pours out.

The following articles come from the electronic magazine OneZero (the first is from November 2019 and the other two from January 2020) and quite vividly describe the prevailing trend in the techno-military complex that directs the operations of the American army: electronic profiling on a planetary scale, looting of personal data, hyper-accumulation of information in databases and the potential conversion of anyone into a target of military action.

The first two articles specifically concern the American army and the global digital surveillance system it has established. The third concerns the extension of these electronic profiling technologies at the expense of immigrants trying to enter US territory. From these articles it becomes clearly apparent how all existing and new databases have begun to interconnect, creating a global panopticon. So that the allegedly surgical precision of “smart” weapons can become a planetary-scale experience…

Harry Tuttle

here’s how the US military’s mass facial recognition system works

documents show how the military collects biometric data from around the world

Over the past 15 years, the U.S. military has enriched its arsenal with a new addition. This new weapon is being deployed worldwide, nearly invisible, and grows stronger day by day. This weapon is a massive database, filled with millions of photographs of faces, irises, fingerprints, and DNA data—an biometric dragnet containing information on everyone who has come into contact with the American military abroad. The 7.4 million identities in the database span from suspected terrorists in active combat zones to allied forces’ soldiers being trained alongside American troops.

“Depriving our adversaries of anonymity allows us to focus our deadly power. It’s like removing the camouflage from the enemy’s arsenal.” These are the words of Glenn Krizay, director of the Defense Forensics and Biometrics Agency (DFBA), in a report obtained by OneZero. The DFBA is tasked with overseeing the database, officially named the Automated Biometric Information System (ABIS).

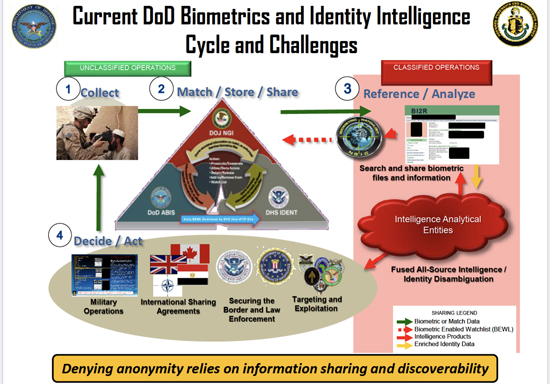

The DFBA and the ABIS database have received minimal attention or publicity, despite their central role in the secret operations of American armed forces. But a presentation that leaked along with notes written by Krizay, director of the DFBA, reveals how the organization operates and how biometric identification has been used to identify non-American civilians on the battlefield hundreds of times, in the first half of 2019 alone. ABIS also allows various branches of the military to flag individuals of interest, recording them in the so-called “Biometrically Enabled Watch List” (BEWL). Once flagged, these individuals can be identified through surveillance systems in battlefields, near borders anywhere in the world, and on military bases.

The presentation also sheds light on how the biometric systems of the military, states, and law enforcement agencies are interconnected. According to Krizay’s presentation, ABIS is linked to the FBI’s biometric database, which in turn connects to state, judicial, and police databases. This means that ultimately, the U.S. military already has access to biometric data of American citizens and registered non-citizens. The DFBA is also in the process of linking its database with the Department of Homeland Security’s biometric database. This network would practically correspond to a global surveillance system. In his notes, Krizay highlights a hypothetical scenario, according to which, the data of a suspect in Detroit would be cross-referenced and checked against information collected “on some mountain peak in Asia.”

The relevant documents were obtained following a request under the Freedom of Information Act. These are documents that were previously used earlier this year, in a closed conference on military use of biometrics, known as the Identity Management Symposium.

ABIS is the result of a massive biometric investment by the U.S. military. According to federal registry analysis, the military has invested more than $345 million in biometric database technology over the past 10 years. Leidos, a company that undertakes contracts with the military and specializes in information technology, is the one that has taken over the management of the database. Ideal Innovations operates a sub-unit of the database, specifically designed for operations in Afghanistan, according to documents obtained by OneZero.

These contracts, combined with revelations about the military’s activities on massive biometric databases, outline a dangerous situation: a large and continuously expanding network of surveillance systems managed by the military, present wherever the US has deployed military forces and absorbing enormous amounts of data from millions of unsuspecting individuals.

The army’s biometric program began in 2004 and was initially focused on collecting and analyzing fingerprints. “In a borderless war, without uniforms or defined fronts, knowing who the enemy is is essential,” wrote John Woodward, head of the Department of Defense’s biometrics unit, in a 2004 report. That year, the Department of Defense assigned Lockheed Martin the task of creating a biometric database with an initial budget of $5 million. Progress was very slow: in 2009, the department’s inspector general reported that the biometric system still had many significant gaps. In tests conducted, the department was able to achieve only five successful identifications out of 150 searches within the biometric data. A new contract later with the defense company Northrop resulted in equally disappointing outcomes, with reports of “system instability, inconsistencies in processing, system overload, operational errors, and delays in data updates of up to 48 hours.”

Since 2016, the Department of Defense has begun making serious investments in biometric data collection. That year, Deputy Secretary of Defense Robert Work identified biometric identification as a critical dimension of almost all department activities: combat, intelligence gathering, law enforcement, security, operations, and counterterrorism. Military leaders began talking about biometric technology as something that would change the rules of the game, and guidance from the Department encouraged analysts to use the technology, but also soldiers in the field. Units were ordered to collect biometric data whenever possible.

That same year, a defense company named Leidos, which had acquired the largest portion of Lockheed’s division dealing with government IT work, closed a $150 million contract to build and develop the system we now know as ABIS.

Between 2008 and 2017, the ministry added more than 213,000 individuals to the BEWL, the biometric-based watchlist. During the same period, the Department of Defense apprehended or killed more than 1,700 people worldwide, based on biometric identifications.

Krizay’s presentation includes data showing that the U.S. used biometric identification to locate 4,467 individuals from their BEWL list in the first six months of 2019. The presentation provides detailed numbers: 2,728 of these identifications involved “adversary forces” and were achieved “in the field” or in areas from which American forces are managed.

The DOD claims to have data on 7.4 million unique identities in the ABIS database, with the majority of these having been drawn from military operations in Afghanistan and Iraq, according to the service’s website.

This number is constantly growing. The data shows that the Department of Defense can collect data from detainees, voters, watchlists from allied countries, employee performance evaluations, or from information provided to the military.

“Almost every operation gives us the opportunity to collect biometric data,” explains a 2014 document on biometrics in the military. “Although quality is preferable to quantity, maximizing the records in the database will result in identifying more persons of interest.”

ABIS also allows different companies and missions to create their own biometric watchlists. These databases can be installed on portable military devices used to scan fingerprints and irises, as well as to combine facial images from the database. «The combination of a known identity and information we possess allows us to decide and act with better focus and, if necessary, with greater lethality,» wrote Krizay in his presentation.

However, much remains unknown about how DFBA and military services use facial recognition and biometric data. A request we made under the Freedom of Information Act to obtain data regarding surveillance systems was blocked by the Ministry of Defense. «Disclosure would be equivalent to unrestricted access to the material by foreign actors,» the response letter stated.

In the text of the presentation at the annual identity management symposium, Krizay provides some insights into the future of DFBA and ABIS. “We will continue to have the need to uncover competitive agent networks, to identify and locate forces driven by our adversaries, to guard the rear and communication lines, to record war prisoners and to locate high-value individuals,” he wrote. According to the presentation, the agency’s goal is to integrate biometric data into the core of security measures. “We already know that we cannot protect our personnel-related systems,” he wrote. “If wikileaks can obtain more than half a million of our reports, then what can China or Russia do?”

DFBA also plans to better interconnect ABIS with other similar databases of government services. Although DFBA has been characterized as the army’s central point for digital processing of biometric data, the service cannot yet share information with the biometric system of the Ministry of Interior Security, due to incompatible formats. In 2021, the ministry intends to award a contract for a new version of its biometric program, a version that will migrate the identification program to the cloud and add new capabilities.

Meanwhile, critics of facial recognition and biometric technologies, both inside and outside the government, are concerned about the accuracy of the technology, privacy violations, and how it will be used, especially in relation to biases that are inevitably introduced into the machine training process.

Tests conducted by the American National Institute of Standards and Technology showed that Black women are ten times more likely to be misidentified compared to white men. On the battlefield, such discrepancies can lead to fatal consequences for people who are misidentified by automated systems.

“It is almost impossible to reach a point where every demographic group—whether related to gender, race, or age—will have the same representation in the system,” stated Charles Romine, the institute’s computer science director, before the congressional committee responsible for the Department of Homeland Security in June 2019. “We simply want to know exactly how much discrepancy exists.”

The executives of Leidos, the company that builds ABIS, do not share the same concerns about the accuracy of their data. “It is noteworthy that the latest tests of the national institute of standards and technology show that our top algorithms actually work better with black than white faces” writes John Mears, vice president of Leidos on the company’s website. It is not clear which of the tests posted on the institute’s website Mears was referring to, but when we contacted them to verify the claim, the institute did not confirm it.

«As a general statement it is not correct» a representative of the institute told us, adding that a study concerning the demographic data of facial recognition technologies is underway. Leidos declined to comment and referred us to the Department of Defense for answers when asked how it addresses allegations of bias in facial recognition algorithms.

Technological challenges do not slow down the adoption of biometrics. It is unclear how many identities have been added to ABIS since Kirzay made his presentation or since DFBA updated its site. All indications converge on the fact that the army is enhancing its capabilities in collecting more and more data. As this data becomes increasingly connected with sources such as the Department of Homeland Security, the American military’s surveillance system grows ever stronger.

“We are not wandering in the dark,” Kirzay wrote in his presentation. “We know who everyone is and most of what they have done.”

The army develops facial recognition technology from long distance that works in the dark

infrared radiation cameras detect the heat emitted by the face

The American army has invested more than 4.5 million dollars in developing facial recognition technology that reads the pattern formed by the heat emitted by the face, aiming to identify specific individuals. The technology will be able to work in the dark and at great distances, according to announcements posted on a website with federal budget expenditures.

Face recognition is already being applied by the military, which uses the relevant technology to identify specific individuals on the battlefield. But current recognition technology usually relies on photographs taken with conventional cameras such as those of CCTV networks or mobile phones.

Now the military wants to develop face recognition systems that analyze infrared radiation photographs to identify individuals. The military research laboratory had previously published related research, but the latest announcements, which began in September 2019 and extend through 2021, show that the technology is now being intensively developed for use in the field.

“Sensors must respond to specific environments, such as targets behind vehicle windshields, targets with backlighting, and targets that are blurred due to weather conditions (e.g., fog),” the Ministry of Defense specifies in the specifications of the proposals to be submitted.

The Ministry also stipulates that the technology must be such that it can be integrated into devices small enough to be carried by one person. The device must be capable of operating from a distance of 10 to 500 meters and to identify faces from a watchlist.

According to information that became public, the Defense Forensics and Biometrics Agency (DFBA) directly oversees the development of the technology. Not long ago, OneZero had reported in one of its articles that the DFBA is responsible for the entire facial recognition, fingerprinting, and DNA analysis program of the Department of Defense. Will Graves, who is referred to as the department’s spokesperson in the announcements, has represented the DFBA at several industry conferences since 2018.

Two are the companies that work on the technology on behalf of DFBA, Cyan Systems and Polaris Sensor Technologies.

Polaris is based in Huntsville, Alabama and sells infrared image processing technology in order to highlight hidden details. The company promotes its products for military and industrial use and from monitoring systems. In 2018, the company collaborated with Exxon Mobil on research into how infrared cameras can be used to detect oil spills. Polaris also has a patent registered specifically for facial recognition with infrared, which was issued in June 2019. The patent concerns how a thermal photograph can be processed in order to dramatically increase the level of detail.

Cyan Systems also holds a patent for thermal image processing, but is more secretive about its technology.

Long-range infrared facial recognition has the potential to dramatically increase the military’s ability to identify individuals passing by even half a kilometer away from military personnel. According to ministry requirements, the new device will be used to identify individuals from a given watchlist rather than scanning the entire DFBA database.

Relatively little is known about how the military uses facial recognition, but ongoing investments in the technology show that the military considers it a priority.

“The combination of a recognized identity and the information we have allows us to decide and act with maximum focus, and if necessary, lethality,” the DFBA director had written in a presentation a year ago.

the omniscient future: mass collection of DNA data of immigrants by the american government

the genetic data will be added to the FBI’s database for violent criminals

This week [stm: early January 2020], the US government will begin collecting DNA samples from thousands of people held by the immigration service, including minors, and will include this genetic information in a massive FBI database used for solving violent crimes, according to the Department of Homeland Security.

This measure had been proposed by the Trump administration in October as an enhancement to the legal framework for immigration and signals a major expansion of DNA collection in the US. In 2018, the Department of Homeland Security had submitted nearly 7,000 DNA samples to the FBI. With the new program, it is expected to deliver over 750,000 samples annually. Anyone who undergoes fingerprinting – including American citizens, green card holders, and temporary detainees – may be forced to provide a saliva sample, according to a privacy impact report released to the public by the department on Monday, 6/1/2020 [Note: such reports are mandatory in the US when a process involves personal data].

Experts in personal data issues and human rights advocates support that major risks are created for those who are detained and their families, pointing out that genetic information could be misused, even for the purpose of mass surveillance. “This is an unprecedented shift from collecting DNA from people accused of specific acts, to people who belong to a category,” says Saira Hussain, a lawyer at the Electronic Frontier Foundation, a non-profit organization for digital rights based in San Francisco.

The new program is the latest to expand the amount of biometric data the government collects from migrants, refugees and asylum seekers. Last year, the immigration service began using a rapid response DNA test on children and their parents at the southern border, aiming to tackle child trafficking networks and “fake families”. The new program paves the way for DNA collection not only when there is suspicion of committing a crime, but also for much less serious reasons. Under the current framework, DNA samples are collected in all states in cases of crimes such as sexual assaults and murders, but illegally entering the US for the first time is considered a misdemeanor. Only a few states, such as New York and Virginia, have proceeded to collect DNA even in certain misdemeanor cases. But the new Department of Homeland Security program will encourage other states to follow.

“To the extent that collecting and processing DNA samples has become faster, cheaper and easier, the legal framework that allows it is becoming increasingly loose,” says Hussain. A bill in Virginia proposes extending DNA collection even to cases of minor violations, such as trespassing or petty theft from stores.

A law passed by Congress in 2005 authorized the collection of DNA samples from individuals arrested or detained by federal authorities. An exception protecting detained immigrants had been in effect since then, but in August 2019, an independent federal agency (U.S Office of Special Counsel) stated in a report that the border protection service “violates this law and ignores the exception over the past decade.”

According to the new directive from the Department of Homeland Security, DNA collection will be rolled out in phases over the next three years. In the first phase, the border protection service in Detroit, at the border with Canada, and at an immigrant intake port in southwestern Texas, near the border with Mexico, will begin collecting saliva samples from children as young as 14 who have been arrested or charged. Gradually, it will expand to every border station and intake port and may include anyone arrested by the U.S. government.

Individuals who refuse to undergo DNA testing may be charged with non-compliance. The few exceptions to DNA collection involve people undergoing legal entry procedures into the U.S., individuals with intellectual disabilities, and patients transported for medical reasons.

Many questions remain regarding what the government can do with the data collected from immigrants and how it might use it in the future.

Under the new regulations, border patrol agents will send DNA samples to the FBI, which in turn will process and analyze them in its laboratories. Subsequently, this data will be entered into a national database called the Combined DNA Index System (CODIS). This database contains the genetic profiles of nearly 18 million convicted criminals and individuals arrested for committing serious crimes. The database allows law enforcement to compare DNA samples taken from suspects or crime scenes with the DNA of known criminals in order to identify perpetrators. CODIS is also used to locate missing persons or unidentified individuals.

In its statement regarding the potential privacy violation, the Department of Homeland Security argued that even if someone’s DNA matches samples in the database, it is unlikely to be used for public safety or law enforcement purposes, since by the time the sample is analyzed by the FBI and entered into CODIS, that person will probably no longer be in U.S. custody.

In any case, there is no provision for individuals whose DNA is collected under the new program—including children aged 14 to 18—to remove their data from the database. Under normal circumstances, U.S. citizens who are arrested for crimes can request to have their DNA removed from CODIS if they are acquitted, charges are not filed, or charges are dropped. However, the department’s announcement does not mention any way for non-citizens to do the same, noting additionally that DNA samples collected from minors can remain available to the FBI “indefinitely.”

The private lives of family members of individuals subjected to DNA testing are also at risk. “This mass DNA collection exposes not only individuals, but also their families in the U.S. and abroad to serious risks,” says Katie Hasson, director at the Center for Genetics and Society at the University of California, Berkeley. For example, many states use CODIS for familial searches of biological material if there are no exact matches in initial searches. This means that family members of detained immigrants may be subjected to intrusive investigations.

It is unclear whether the Department of Homeland Security will share the DNA it collects, and if so, with whom. The possibility that samples might be shared with other governments creates risks for asylum seekers, especially those recognized as refugees. “There is fear that the most sensitive personal information will end up in the hands of exactly those governments they have fled from,” says Hussain.

While supporters of DNA collection claim the practice will help solve crimes, many experts worry that adding hundreds of thousands of DNA samples to CODIS will increase the likelihood of innocent people being implicated in crimes. Every day, a person sheds millions of skin cells containing their DNA, which can end up on objects they have never touched. Simply because someone’s DNA is found at a crime scene does not mean that person is guilty.

The US government is particularly critical in cases of forced DNA sampling in other countries, especially in China, where DNA and other biometric data are collected from Muslim Uighurs even if they have not been convicted or are not even considered suspects of any crime. But the new Trump administration program dangerously approaches what is happening in China, to the extent that it is already collecting a large amount of biometric information from non-citizens. Already, the Department of Homeland Security has proceeded to take fingerprints from children and collect iris scans from adults.

However, DNA provides much more information about an individual compared to fingerprints, which are exclusively an identification method. DNA, on the other hand, can reveal ancestry, familial relationships, and personal health information. Moreover, scientists are seeking and will eventually find ways to determine behavioral patterns, sexual preferences, and intelligence from a person’s biometric data.

Current technology cannot yet deduce an individual’s facial image using only DNA, but American companies such as Parabon Nanolabs are developing programs that narrow down possible images, and similar technology is also being developed by China. If this technology is developed, it could serve in capturing criminals, but it could also result in new surveillance tools capable of recognizing faces.

Many are concerned that if the government retains DNA samples indefinitely, it will open the door to future abuses against vulnerable and marginalized groups. People of color are already overrepresented in CODIS and other police databases, and the new regulations will surely worsen this inequality.