Both politicians in their election campaigns and corporate executives at their conferences warn about an impending crisis due to automation – a crisis where workers will be replaced, gradually at first but abruptly at some point, by intelligent machines. What they avoid saying with their warnings, however, is the fact that the crisis due to automation has already begun. The robots are here, already working in management, sucking the last drop of blood from the workers.

They monitor hotel cleaners, guiding them to the next room that needs to be cleaned and recording their speed. They oversee programmers, tracking their clicks and scrolls on their screens, deducting from their salary if their pace is slow. They listen to workers in call centers, instructing them on what and how to say things and keeping them constantly busy at the highest possible rate. At the same time that we anxiously await when autonomous trucks will hit the roads (in five years they’ll be here, we hear every year), robots are already here in the form of the supervisor, the foreman, the manager.

These automated systems can detect inefficiencies in production that would be impossible for any manager to spot – the momentary pause between two calls, the bad habit of wandering around the coffee machine right after finishing a task, a new route, which, if all goes well, increases the packages that can be delivered within a day. For the workers, however, whatever is flagged as an inefficiency by an algorithm was for them the last refuge of rest and autonomy. As these micro-breaks and micro-freedoms are sifted out as waste by optimization algorithms, their job becomes increasingly intense, increasingly stressful, increasingly dangerous. For several months now, I have spoken with over 20 workers from six different countries. For many of them, their greatest fear is not that robots will take their jobs, but that robots have already become their bosses.

Amazon is perhaps the most characteristic case of the dangerous effects that automation of work management can have. Almost every aspect of its warehouse management is run by some software package: from working hours and pace to when someone gets fired because they can’t keep up with this pace. Each worker has their own “quota” (a specific number of items that must pass through their hands per hour) and if they fail to meet it, there is a chance they will be automatically dismissed.

When Jake started working in a warehouse in Florida, he was initially impressed by how few supervisors there were: just two or three managers for a workforce of 300 workers. “All the management was automated,” he had told me. One of the supervisors would walk back and forth with a laptop in hand, identifying workers who were lagging behind and telling them to speed up (Amazon claims that its system alerts managers about workers they need to speak to regarding their low performance, and that all final decisions regarding staff, including dismissals, are made by the supervisors themselves).

Jake, who used a pseudonym out of fear of reprisals, did the job of “repositioning.” What he had to do was take an item from a conveyor belt, press a button, place the item in whichever compartment a screen indicated, press another button, and do all this over and over again. He compared his job to continuously performing a stretching exercise every 10 seconds. Even so, the giant scoreboard in the warehouse that showed a cartoon character running alongside the speed of the 10 fastest workers encouraged him to move even faster. Every so often, a manager would come on the loudspeaker and make announcements, as if it were a sports broadcast: “For the first half, we have Bob in third place with 697 units per hour.” Top workers received Amazon coupons that they could redeem for company devices and t-shirts. Those who scored low were fired.

“You never stop,” Jake told me. “Literally, you never stop. It’s like, from the moment you leave your house, you have to run non-stop for 10 hours, without stopping for any reason.”

After several months, he began to feel a burning sensation in his back. A supervisor had told him to bend his knees more each time he lifted something. Jake did try this, but the result was that his performance dropped, and so another supervisor told him to increase his speed. At that moment he thought: “Are they kidding me? Go faster? If I go faster, I’ll get injured and collapse.” Eventually, at some point his back betrayed him. The diagnosis included two damaged discs and so he had to live with disability benefits. According to him, the speed of work was 100% responsible for his injury.

All the Amazon workers I have spoken with have told me the same thing: what makes the job so dehumanizing is not so much the physical difficulty as the automatically imposed pace. The system is constantly optimized to avoid even the slightest slack and any opportunity for rest. A worker on the west coast told me about a new device that shines a light on the object he needs to pick up, allowing Amazon to accelerate rates even further and thus eliminate even the “micro-breaks,” as he calls them, that he manages to steal in those fleeting moments when his eye searches for the next item on the shelf.

It is impossible for a person to withstand such work rates without collapsing. ProPublica, BuzzFeed, and several others published last year some investigations regarding Amazon, where they report cases of delivery workers running like crazy between cars and pedestrians in their attempt to deliver their orders, following difficult routes, such as those that arise and are algorithmically recorded via an application on their mobile. In November, Reveal analyzed various documents from 23 Amazon warehouses and concluded that about 10% of full-time workers were seriously injured in 2018, a figure that is almost double the national average for this type of job. I have heard from various Amazon workers that such repetitive injuries due to work stress have reached epidemic proportions, but that reports are rarely made (an Amazon spokesperson said that the company takes worker safety very seriously, that it has medical staff available on-site, and that it encourages workers to report all injury cases). Back and leg pain, as well as various other symptoms from constant strain, are so common that Amazon has installed automatic painkiller dispensers in its warehouses.

This relentless stress burdens in other ways too, however. Jake remembers that at some point he started shouting at his colleagues on his own to go faster, only to begin wondering a little later what had gotten into him and eventually to apologize. The fatigue after the end of his shift was so great that, as soon as he got in his car, he would fall asleep directly in the company parking lot and only after waking up would he start the engine and go home. “There were many who did this,” he told me. “The idea behind the 40-hour week was that you work for eight hours, sleep for eight hours, and you have another eight hours left to do whatever you want. But what happens if, when you get home, you collapse into sleep and sleep for 16 hours? Or if on your day off you constantly feel as if you’ve woken up after a bad hangover, feel lousy, can’t concentrate on anything, and lose your sense of time due to the effects of work and a stressful, tiring condition?”

Inevitably, at some point workers reach the point of “burnout,” but they are easily replaceable from the moment machines can dictate their every move. Jake estimates that he was hired along with 75 other individuals, but when his back finally betrayed him, he was the only one left, and in most positions there had already been two replacements. “You’re just a number. They can replace you with anyone within two seconds,” he says. “No qualifications needed. They need nothing. The only thing they care about is that you work very fast.”

In Amazon’s warehouses, one will find robots among those that steal our jobs, but it’s not this type of robot that worries workers the most. In 2014, Amazon introduced robots that transport items to and from shelves, automating the work of retrieving products. These robots proved so successful that eventually more workers were needed at other posts to maintain a high work pace; Amazon built more facilities and now has three times as many warehouse workers as it had before introducing the robots. However, the robots changed the nature of the work: workers, instead of moving around the warehouse, were now confined to their stations simply receiving the items brought to them by the robots. Workers claim that this particular post is one of the most demanding and exhausting jobs within the warehouse. Reveal uncovered that injuries were more frequent in warehouses with robots, which should come as no surprise since the issue is the fast pace. Workers are more concerned about these machines that impose such rates.

Last year, a wave of worker protests erupted at Amazon facilities. Almost everywhere, the cause was automated management that leaves no room even for the most basic human needs. A worker in California was automatically fired when she exceeded her unpaid leave limit by one hour due to a death in her family (she was rehired following a request from her colleagues). Workers in Minnesota walked off their posts in protest against accelerated pace rates, which were responsible for injuries and left no time at all for bathroom visits or for observing certain religious customs. The workers’ feeling was that, in order to satisfy the machines, they themselves had to become machines. Their slogan was: “We are not robots.”

Just as industrial revolutions involve stories of technological discoveries, they also involve the issue of how labor is organized. Steam engines and stopwatches were available for decades before Frederick Taylor, the high priest of optimization, used them to organize the modern factory. While working in a steel mill in the late 19th century, he managed to simplify and standardize all positions and recorded his instructions in notes; he timed each task accurately to the second and set an optimal pace. In this way, he managed to remove the control that skilled craftsmen had over production, thus starting an era of industrial development, but also of demeaning, repetitive, and dangerous jobs.

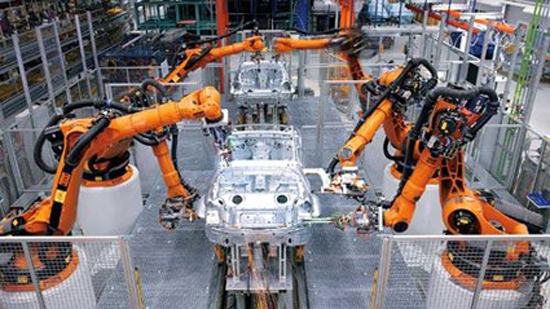

The one who managed to prove the advantages of the new method in the most convincing way was Henry Ford, by further simplifying tasks and organizing them in front of an assembly line. The speed of the line determined the workers’ pace and gave supervisors an effective tool to check who was slacking off. It was something the workers disliked. The work became so exhausting and boring that resignations began to fall like rain, forcing Ford to double wages. As the application of such methods spread, strikes and voluntary slowdowns as protests against “speeding up” (cases where supervisors increased the line speed to rates that no one could keep up with) became a common phenomenon.

We are in the midst of yet another major acceleration. There are many causes for this acceleration, but one of them is certainly the digitization of the economy, along with all the various ways it reorganizes labor. An example is retail: workers no longer stand around aimlessly in the store waiting for the next customer; due to e-commerce, their role has undergone a fission. Some work in warehouses, fulfilling orders nonstop, while others work in call centers, answering an endless stream of questions. Workers are under close surveillance in both of these settings. Every move they make is recorded by warehouse scanners and call center computers, feeding data to automated systems that force them into overintense labor.

Automated management, in its most basic form, starts with scheduling. Scheduling algorithms have existed since the late 90s, when stores began using them to predict customer traffic and accordingly schedule employee shifts. These programs did whatever an owner would do, assigning fewer workers to morning shifts when traffic is light and more during the afternoon, trying to maximize sales per employee. However, the algorithms simply proved better and continued to improve by incorporating the ability to take various factors into account, such as weather or any sporting events in the wider area. At some point, they reached the point where they could predict staffing needs with fifteen-minute accuracy.

According to Susan Lambert, a professor at the University of Chicago, these specific software packages are so accurate that they could be used to create schedules that are more human. However, they are often used for the opposite purpose: to produce a schedule with the minimum possible number of workers—or even slightly fewer—who can handle the anticipated workload. This is not necessarily the most profitable practice, as she points out, citing a study she conducted in Gap stores: for companies and investors, it is easier to quantify cuts in labor costs than lost sales due to customer dissatisfaction from being left alone wandering in empty stores. But if it’s a bad situation for customers, it’s even worse for workers who are forced to run around all the time trying to cover the gaps in a business that is perpetually understaffed.

Although they started in retail, scheduling algorithms are now everywhere. For example, in Amazon’s facilities where products are sorted before being shipped, workers are initially given a very general schedule and then, via an app, they are notified whenever extra hours arise in the warehouse, which can happen even 30 minutes before the start of their shift. As a result, no one can afford a break anymore.

Networking technologies, cheap sensors, and machine learning algorithms have allowed automated management and monitoring systems to become even more sophisticated – and this not only in structured environments such as warehouses, but anywhere workers carry their mobile phones with them. Gig platforms like Uber were among the first to exploit these new technologies, but the same quickly happened in other sectors as well, such as delivery companies and restaurants.

There was no single revolutionary moment; however, just like in the case of the stopwatch, revolutionary technology can seem boring until it becomes the foundation upon which work is organized. Each time a work pace monitoring program is installed in a warehouse or a GPS device is placed in a taxi, management possibilities open up to such a depth and extent that they seem drawn from Taylor’s dreams. The cost of hiring several managers to time all the movements of workers in a warehouse or truck drivers would be prohibitive, but now only one is needed. This is the reason why all those companies that readily adopt such practices look very similar in their structure: a large mass of low-paid, easily replaceable part-time workers (or contractors) at the base; and at the top, a small group of highly paid employees who design the software that manages those at the base.

It is not the industrial revolution that people like Elon Musk, Mark Zuckerberg, and other Silicon Valley residents constantly warn us about. These individuals remain obsessively attached to the specter of an artificial intelligence that will eliminate our jobs, something presented as radically new and extremely alarming – something like a bulldozer that will flatten our society, according to Andrew Yang’s words. Like all revelatory visions, this one appears excessively flattering to the high-tech industry, which finds itself in the privileged position of warning the rest of the world about its own success and the forces it has unleashed that will render human labor obsolete forever. However, by looking at an entire civilization from such a lofty and abstract perspective, this perception loses sight of how technology transforms work, while at the same time, the fatalism that characterizes it leaves no room for sympathy or concern for all those people who become objects managed by machines. Why should anyone protest about the working conditions of warehouse workers, taxi drivers, and call center employees when everyone says they too will be replaced by robots in a few years? What these types like Musk and Zuckerberg have to offer is as abstract as their diagnoses, and essentially amounts to giving money to those who will be replaced by robots whenever that happens.

At some point, robots might eventually replace truck drivers and all of us together, although so far the impacts of automation on the labor market have not been that devastating. As in the past, it is certain that technology will push some into unemployment and it is important that there be a safety net for these people. According to an analysis by the UC Berkeley Center for Labor Research and Education, however, a different but quite likely scenario predicts that drivers will not become unemployed, but will continue to travel within their essentially autonomous truck in order to assist on difficult roads within cities, earning less money to do a de-skilled and strictly monitored job. Or they may be transformed into office workers in a call center, remotely fixing any problems with the trucks, with their efficiency constantly monitored by an algorithm. In short, machines will reach the point of managing them, as a result of forces and tensions that have been increasing for years, but which go unnoticed due to this fetishism with artificial intelligence.

“The Robotic Revelation is already here,” according to Joanna Bronowicka, researcher at the Center for Internet and Human Rights and former candidate for the European Parliament. “The issue is simply that the way we have constructed all these narratives conceals how real people are living their lives here and now. We have people from both the left and the right, but also people like Andrew Yang, participating in this discussion using a language of the future.”

This does not mean that workers should not worry about the future development of artificial intelligence. Until now, a job could only be automated if it could be broken down into small sub-tasks that could be measured by machines, e.g., a route recorded via GPS or an object scanned in a warehouse. However, machine learning is now capable of handling data that is not so strictly structured and thus deliver new jobs into the hands of robot-bosses, such as typing on a computer and conversations between humans.

Angela had been working for years at the call center of an insurance company until she resigned in 2015. Her job was quite stressful, as often happens in call centers: customers out of their minds, algorithms counting the number and duration of calls, and managers secretly listening in to see how things were going. Last year, when she decided to return to a similar position, she noticed that something had changed. Besides all the usual metrics, there was now something else that had become measurable through artificial intelligence: emotion.

The software package responsible for this task had been built by Voci, one of many companies that use artificial intelligence to evaluate call center workers. Angela scored exceptionally well on all other metrics, but the program consistently gave her low scores for sentiment, which puzzled her, given that her (human) managers had previously praised her for the high degree of empathy she displayed on the phone. No one was able to tell her exactly why the program was penalizing her in this way. She suspected that the program was interpreting her fast and assertive speaking style, expressions of sympathy toward customers, and periods of silence (which resulted from efforts to meet a quota aimed at minimizing the number of customers on hold) as negative.

“I wonder if the program ultimately rewards a kind of fake empathy, that fits with expressions of the type: ‘Oh, I’m very sorry you’re facing this problem,'” says Angela, who asked to use a pseudonym out of fear of reprisals. “It’s very limiting to feel that the only way to show some emotion is to do it the way the machine dictates. Beyond that, it doesn’t seem to me to be the best thing for customers either. If they wanted to talk to a machine, then they would have chosen to continue with IVR (Interactive Voice Response).”

A Voci representative said that the company has trained its program with thousands of hours of audio data collected from employees and labeled as negative or positive emotions. He admits that these assessments are quite subjective, but says that the volume of data allows the tone and voice quality to be taken into account. This representative said that, ultimately, the company provides an analysis tool and that it is up to call centers how they will use the data provided to them.

Angela’s experience with the Voci program made her a bit cautious about the new round of automation. The call center where she worked had embarked on installing a Clarabridge program designed to automate certain parts of call evaluations still done by humans, such as whether call agents used the correct phrases. The center also planned to expand its use of Cogito, which uses artificial intelligence to train workers in real time, telling them when to speak more slowly, with more energy, or to express empathy.

Every time a list emerges with the jobs most at risk of falling victim to automation, call center workers are immediately placed just below truck drivers. Their job has a repetitive nature, and machine learning has made rapid progress in voice recognition. However, machine learning struggles with certain highly specialized and unique tasks. Moreover, customers often simply want to speak to a real person. As a result, it is the managers’ jobs that get automated. Google, Amazon, and a host of other smaller companies have built artificial intelligence systems that listen to calls and train or even automatically evaluate workers. For example, CallMiner advertises an AI system that evaluates workers in terms of their professionalism, politeness, and empathy—and, as an promotional video informs us, it can measure all these with an accuracy of a fraction of a percentage point.

According to the workers, these systems often prove to be very clumsy judges of human communication. One worker mentioned that he had managed to meet his empathy quota simply by continuously saying “sorry.” Another worker at an insurance company’s call center said that Cogito’s AI system, which is supposed to tell her to express greater empathy whenever it detects that a customer is feeling unpleasant emotions, was so sensitive to minor tonal differences that even a laugh managed to trigger it. A colleague of hers had a call where the automatic empathy alarm went off so many times that supervisors called her into their office. When they listened to the call, it turned out that the customer was laughing throughout out of joy for the birth of his child. However, since the worker was busy filling out various forms, he wasn’t paying much attention to the conversation, merely obeying the AI system that kept telling him to respond with a “I’m sorry,” to the customer’s surprise.

According to Cogito, its system “is highly accurate and rarely gives wrong answers,” but in the few instances when such a thing happens, since it simply operates as an aid and does not replace workers, they should be able to use their judgment on a case-by-case basis.

It is of course important that these systems can be evaluated for their accuracy, but an even more fundamental question arises: why is there such eagerness from so many companies to automate empathy? The answer has to do with how automation itself has intensified work.

Until a few years ago, call center workers were called upon to handle all kinds of cases, from some quite complex or emotionally charged ones, to some fairly simple ones, like “I forgot my password.” However, robots have now taken over the easy cases. “There are no longer those easy calls that allowed a worker to catch a mental breath as happened in the past,” says Ian Jacobs of the research firm Forrester. Automated systems also work in collecting information from customers or filling out a form, tasks that previously would have somewhat facilitated a worker, except now any pause is recorded to be immediately “filled” with more calls.

For example, the worker using Cogito’s system had only one minute between two calls to complete a form and just 30 minutes per month for bathroom breaks and personal time. She had to handle a series of calls from people who were suffering from incurable diseases, others who had lost family members, others who had to report a miscarriage, and a host of other traumatic events. Each such call had to be completed in under 12 minutes, and she did this for 10 hours every day. “It makes you desensitize,” she says. Some workers suffer from chronic anxiety and insomnia as a result of endless days spent in emotionally charged conversations, while at the same time “you have a computer over your head deciding arbitrarily whether you’ll be fired or not.” This form of “burnout” has become so common in these workplaces that it has been given a name: “empathy fatigue.” In an e-book, Cogito explains why it uses artificial intelligence and notes that call center workers resemble nurses who become desensitized during their shifts. It also points out that workers’ job quality declines after the first 25 calls. According to the company, the solution is to use artificial intelligence to provide “empathy at scale.”

One of the common wisdoms of our times is that interpersonal skills such as empathy will be among those that remain under human control in the age of robots. And this is usually considered an optimistic view of the future. However, call centers are an indication of how this future can become darker: automated systems that require workers to have increased levels of empathy and that try to extract from them even their last drop of empathy or, after all, a mechanical simulation of it. Angela, the worker who had found her match with Voci, believes that, as artificial intelligence is used to compensate for the consequences of inhumane working conditions, it may ultimately lead to an even greater dehumanization.

“No one likes to call a service center,” says Angela. “The good part of my job is that I can give a more human face to this process, use my own personal style, build a relationship with the customer and make him feel that someone cares about him. That’s what gives meaning to my job. But if you automate everything, then you also lose the ability for a more human connection.”

Mak Rony was working as a programmer in Dhaka, Bangladesh when he saw an advertisement on Facebook from a company based in Austin called Crossover Technologies. Although he liked his job, it seemed to him that the position at Crossover would be a step forward in his professional life: the money was better ($15 per hour) and according to the ad, he would have the flexibility to work based on his own schedule and from his home.

On his first day at his new job, he was told to download the WorkSmart program. Crossover CEO Andy Tryba describes this program in a video as the “FitBit for work.” According to him, the modern worker constantly interacts with cloud applications, thus generating enormous amounts of information about how they spend their time – most of this information is simply treated as garbage. However, he claims that this data should be used to increase productivity. Taking as his reference the popular book by Cal Newport titled Deep Work, which deals with the dangers of distractions and multitasking, he argues that his program will allow workers to achieve ever-deeper levels of focus. Tryba presents a series of graphs, such as one showing the defragmentation of a hard disk, to convince us of how a worker can start their day with their attention scattered, yet eventually manage to spend long periods in uninterrupted productivity.

WorkSmart indeed managed to transform Rony’s days into continuous periods of productivity, since whenever it detected that he wasn’t working hard enough, it didn’t pay him his salary. This particular software recorded the keys he pressed, the clicks he made with his mouse, as well as the applications he ran on his computer, all in order to evaluate his productivity. He also had to allow the program access to his camera. The program randomly took photos three times every 10 minutes to ensure that Rony was at his post. If a photo showed that he wasn’t there, or if the program considered his productivity to be below an acceptable threshold, then he wasn’t paid for that ten-minute period. Another worker who started at the same time as Rony and refused to allow access to his camera was fired.

After some time, Rony realized that, although he was working from home, his old office job offered him more freedom. There, he could at least take breaks and stop for food. In contrast, when working for Crossover, he had to move quickly and strategically even for a trip to his home’s bathroom: he waited for the camera’s green light to turn on so he could quickly dash to the bathroom, hoping he would finish before WorkSmart took another photo.

The norms he was supposed to meet were extremely demanding: around 35,000 lines of code per week. He sat down and calculated that he would need to press 150 keys every 10 minutes; if he paused for a moment to think, this would result in him being marked as “idle” for that ten-minute period. Each week he was required to produce 40 hours of productive work, according to the program’s criteria. If he failed to achieve this, he risked being fired. This meant that ultimately he had to work 10 extra hours unpaid in order to make up for the hours the program considered unproductive. Four more current and former Crossover employees told me the same thing – one from Latvia, one from Poland, one from India, and another from Bangladesh.

“Your social life is the first thing you lose,” says Rony. He stopped going out with his friends because he had to stay glued to his computer to meet his quotas. “I stopped going out at some point and after that.”

As the months passed, anxiety began to weigh him down. He lost his sleep. He couldn’t listen to music while working because the program considered youtube as anti-productive and reduced his salary. The irony of the matter is that the quality of his work started to decline. “If I have freedom, real freedom, then I can withstand the pressure, if necessary,” he says. But under such conditions of daily, intense pressure, he eventually “burned out” and his productivity collapsed.

Tryba claims that his company is a platform that provides specialized workers to companies, along with the tools to manage them. It is up to the companies themselves whether and how they will use these tools. He says that no one should work extra hours without being paid, and that if WorkSmart flags some time as idle, then workers can request their manager to overturn the program’s decision. Whenever workers need a break, they can press pause and stop the timer. When asked why such a degree of monitoring is necessary, he said that remote work would become the form of work of the future, and that it would provide greater flexibility to workers, but that employers would need to find a way for workers to give them an account of what they are doing. In addition, the collected data can be used to train workers on how to become more productive.

Crossover is of course not the only company that saw an opportunity to exploit the data generated by digital workers. Microsoft has its own software, called Workplace Analytics, which exploits the “digital exhaust” left behind by employees as they use the company’s various tools to make them more productive. The “workforce analytics” space has been filled with companies that monitor the digital traces of employees and promise that they can identify chunks of idle time and reduce the number of workers. This optimization process becomes increasingly harsher and more focused on individual workers the lower we go down the pay scale. Time Doctor from Staff.com, which is popular among outsourcing companies, tracks workers’ productivity in real time, prompts them not to stray from their target whenever it deems they have wandered off or are idle, and simultaneously takes photographs from their cameras, just like Crossover does.

Sam Lessin, former senior Facebook executive and co-founder of the company Fin, describes a realistic version of where things are heading. Fin started as a digital personal assistant but eventually changed character and became a worker monitoring and management application (applied, among other things, to the workers who built it). One worker said that handling requests from this “assistant” is like working in a call center but with more intense monitoring and recording of idle time. At the time Fin decided to change character, Lessin published a letter in which he said that mental labor is still stuck in a pre-industrial phase, with workers often sitting in their offices doing nothing and their low productivity not being measured. According to Lessin, the productivity explosion that everyone expects from AI applications will not come by replacing all these unproductive workers, but by applying artificial intelligence to measure and optimize their productivity, just as Taylor did with factory workers. The difference being that here we have a factory that will be in the cloud, with a mass of mental workers managed by an AI program to which companies will be able to address themselves whenever they need, much like they now rent computing resources from Amazon Web Services.

At least Lessin admits it: “The industrial revolution was not something good for workers, at least in the short term.” The cloud factory will cause a wave of globalization and de-specialization. The workplaces that allow high degrees of optimization are already largely meritocratic, says Lessin, but there is a risk that this meritocracy will become dangerous, as shown in the movie Gattaca. However, in the long run, these risks will not be of great significance, as people will be able to specialize in whatever they are truly good at, they will work less, and additionally, they will be able to work more flexibly.

For Rony, Crossover’s promises of flexibility turned out to be a delusion. He couldn’t ultimately withstand all this relentless pressure and surveillance, and after a year he resigned. “I thought I had lost everything,” he says. He had quit his stable job, had lost contact with his friends, and now he was worried about whether he would manage to pay his bills. However, he found another job after three months, a traditional office job. He earned less money, but he was more satisfied. He worked with a manager who helped him whenever he got stuck on something. He had breaks again for rest, a lunch break, and a tea break. “If I can step outside to get some air, to have a laugh and drink my tea, then I feel like I’m in a place where I could even fall asleep. There is a great deal of freedom.”

It has always been the case that working means giving up a piece of your freedom. When a worker takes a job, they may accept that they will allow their employer to instruct them on how to behave, how to dress, or where to be at a given time. And all of this is considered normal. Employers act as if they are private governments (as philosopher Elizabeth Anderson observes), and workers accept the exercise of such power that would seem oppressive if it came from the state, because it is assumed that workers are always free to resign. Beyond this, workers often give their employers wide latitude to monitor them, which is also considered normal and only causes reactions when employers’ long arm intrudes into workers’ personal lives.

The promise of automated management is that it will change these perceptions. Although employers may have always had the right to monitor your computer screen, such a thing would be considered rather a waste of time on their part. Now, however, this kind of surveillance is not only easily automatable, but also necessary in order to collect the data that will guide the optimization of work. This is a logic that seems irrefutable in a company when it is trying to reduce costs, especially if we are talking about large companies, so even marginal improvements in the productivity of individual workers can have significant profit at the end of the day when the sum is tallied.

However, while workers may have tolerated the threat of surveillance as long as it remained somewhat distant and abstract, they react more intensely when data from this surveillance is used to monitor and dictate even their slightest movements. An Amazon worker offered a rather grim description of the future: “Perhaps algorithms will come out connected to devices embedded directly into our bodies to monitor how we work,” he says. “So far, the algorithm simply tells the manager when to yell at us. In the future, that same algorithm could be connected to an electric collar.” I laughed when I first heard these scenarios, but he told me that he was being both serious and half-joking. After all, Amazon has already patented wearable surveillance devices that vibrate to direct workers, and Walmart is testing harnesses that can track workers’ movements in its warehouses. So he turned the question back to me: Is a future really so unlikely where you’ll have the freedom to choose between starving to death or accepting a warehouse job, signing a contract agreeing that you must wear something that delivers a small shock whenever your pace drops? And all in the name of efficiency. “I think that this is indeed a possible development, especially if people don’t become more sensitized and organize better as workers to address all these issues, including how societies are transformed by these technologies,” he says. “These are the issues that keep me awake at night and haunt me even now while I’m in the warehouse.”

This particular worker bases his hopes on unionism and activism that is now flourishing in Amazon’s warehouses. Such reactions are not unprecedented. The same thing happened in the last industrial revolution when workers reacted to increased work rates by organizing and including work rate in the contracts signed between employers and unions.

However, the pace of work is only one of the questions we will be called upon to answer: what is the right balance between efficiency and human autonomy? We now have an unprecedented ability to record and optimize workers’ behavior down to the smallest detail. Is it worth it for so many people to suffer from chronic stress and feel like robots in order to achieve a marginal increase in efficiency?

One could imagine a variation of these systems where data is collected anonymously in order to improve various processes within workplaces. Such a system could have the benefits of optimization while avoiding the personalized surveillance and management that workers find so repulsive. This, of course, would mean that we would inevitably lose some very valuable data. It needs to be understood that sometimes it is worth not collecting data at all, so that we can preserve valuable space for human autonomy.

Recently I discovered on my own the huge difference that the existence of even a small degree of freedom at work can make, talking to a worker who had quit his job at an Amazon warehouse in Staten Island to take a job as a loader-unloader on trucks that make home deliveries. And there he had meters and scanners, but they only measured whether his team was within the daily plan, leaving the workers the freedom to choose their roles and their work pace. “I feel like I’m in paradise,” he told his colleagues.

Josh Dziesa,

the verge.com, 27/2/2020