Alex Karp, founder and CEO of Palantir, spoke via video conference on December 3 with Greek Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis regarding the continuously expanding collaboration between Palantir and the Greek government, aimed at supporting efforts to respond to covid-19. Also participating in the conference were Palantir director Josh Harris and Kyriakos Pierrakakis, Minister of Digital Governance, as new ways were sought to keep Greece above the curve in its health effort.

From the beginning of the pandemic, Palantir has helped the Greek government make data-driven decisions, as part of its pandemic response. The government uses Palantir’s Foundry platform on Amazon’s web services infrastructure to create response dashboards for officials handling pandemic issues. Particularly valuable is the development of a crisis monitoring center for the Greek Prime Minister, which provides a real-time comprehensive overview of the pandemic situation.

“The collaboration with the Greek government was born out of necessity as soon as the pandemic began,” stated Alex Karp. “We immediately played a key role in their efforts to respond to the pandemic, which based on our experience is one of the best in the world, and we are eager to deepen this collaboration in the years to come.”

This is the first report by the news site Business Wire, which announced on December 7 the arrival of Palantir in Greece and its collaboration with the government. On the company’s official website, there is no relevant announcement or press release, and the specific report is simply republished without any comment. Note the date, December 7, as well as the statement by the managing director that “the collaboration was born… right when the pandemic started” and that from the beginning of the pandemic, March 2019, the company “played an immediate key role,” which means that for at least 10 months Palantir has been present in Greece and doing its work, without fanfare and away from any publicity.

Palantir already has an 18-year history behind it, for a data pioneer tech company it should be considered at least “aged”, and from its first steps it systematically took care of two things. The first is to make it clear that it is not “yet another neutral” hi-tech company in the track of generalized “digital well-being”, but it is enlisted to serve the interests of the “West” and especially the USA, and indeed in the hottest and most dangerous fronts such as the “war on terror” or internal security, assigning itself the role of the most pro-military faction of Silicon Valley. The second, a logical consequence of the first, is to conceal behind a veil of secrecy and unconfirmed rumors its real activity in more than 150 countries where it operates.

What we know about Palantir lies mostly at the level of general critique and little in the realm of the directly specific and practical. We know that in recent years it has become the privileged partner of secret, military, police and judicial services, focusing on extracting and processing vast amounts of data scattered across databases, aiming on the one hand to reveal hidden relationships, networks and activities, and on the other to construct models for timely and preventive diagnosis and prediction; in other words, to enhance the “data-driven decision-making process” (as the CEO elegantly put it to the Greek Prime Minister). We know that it embeds its own engineers at the client’s premises (called “forward-deployed engineers” in the company’s military argot), who directly undertake to unravel, combine and process data from every available source. We also know that its operations function de facto on the blurry boundaries between established legal safeguards and restrictions (already eroded by the “war on terror” and now the “war against coronavirus”) and the realm of the digital far-west. We know what lies at the heart of Palantir’s “business” activities: unlimited control and surveillance, the generalized algorithmic panopticon. After all, the strategic goal of the American military-technological complex, of which Palantir is a privileged partner, since 9/11 and beyond, has been precisely this: to be able to “know everything,” so as to accurately predict and direct everything.

But this knowledge does not answer, and could not possibly answer, what the company’s exact plans are now, what specific services it offers, what particular work it actually does. It is the same issue that concerns secret services. We know, for example, what the CIA or the NSA are and their history, but it is inherently unthinkable to know in detail their current operations, except for the rare cases of the WikiLeaks or Snowden type, when the veil of secrecy is temporarily torn apart. The same condition of concealment applies equally to Palantir; the same mechanisms that protect secret services and spread rumors and organized lies to cover up their actions seem to have cast a web of opacity over the company. That is why, moreover, whatever specific information we have about its activities comes from “leaks” and the efforts of anonymous hackers who sometimes manage to bring data to light.

From the time Palantir was founded in 2003, it took 8 full years until it first came into the spotlight, in a way that alluded to a “scandal,” yet suitable for enhancing the reputation of “a company determined for anything.” In early 2011, a series of emails were leaked showing that a Palantir engineer had collaborated on a plan to deal with the potential publication of WikiLeaks documents from the Bank of America. In these emails, the Palantir engineer suggested specific methods to locate and identify the organization’s donors, launch cyberattacks against WikiLeaks’ infrastructure, and even identify and threaten supporters. The company placed the particular engineer on leave, but after an internal investigation into the practices applied, he returned to his position normally.

A Google for spies and agents, this is a fitting description that has been given to Palantir. Indeed, the two companies resemble two sides of the same coin. Both aim, ultimately, to unify, categorize, and process vast amounts of information scattered across countless independent databases; both seek to restore order within informational chaos and algorithmically derive models that accurately reflect live activity. The clientele and operational plans may differ, but in both models, surveillance and oversight lie at their core; the difference is that in Google, the public actively participates in the surveillance, whereas in Palantir, the public is the clear object of surveillance. Google represents the panopticon under normal conditions; Palantir represents it under wartime conditions—it is a Google in campaign gear.

A child of the 11th/9th

The story begins in 2003 in the USA, with two retired military officers, high-ranking officials from the Reagan administration, who had returned to active duty after 9/11. The first was Richard Perle, one of the architects of the first Iraq war that had begun that year, who wanted to introduce the second to a pair of young and promising entrepreneurs from Silicon Valley who had just founded a software company. The startup, named Palantir, aimed to collect data gathered by a wide range of intelligence services—any kind of data, from field spy reports to phone calls, from airport surveillance footage to economic transactions—in order to identify terrorists and prevent attacks on the USA.

The second was John Poindexter, a retired rear admiral, who had served as Reagan’s national security advisor, was the orchestrator of the Iran-Contra affair (the secret and illegal sale of weapons to Iran, in order to use the proceeds to fund the U.S.-backed Contra rebels in Nicaragua) and because of his role had been forced to resign and was criminally prosecuted. After he was ultimately acquitted of all charges, he was recalled to the Pentagon after 9/11 and was placed in charge of the information office at DARPA, with the objective of developing a data mining program, which was as ominous as its name: Total Information Awareness / Comprehensive Information Awareness. His work at DARPA – which had been characterized in the press at the time as “the super-spy’s dream” – served as the precursor to the extensive surveillance system established by the NSA and revealed a decade later by Edward Snowden.

Poindexter, with his extensive background in the deep state, was certainly not the type to be thrilled by the grandiose claims of two young men who had nothing tangible to show for themselves. Yet he was precisely the person Peter Thiel and Alex Karp, the two co-founders of Palantir, were looking for. Their company shared similar ambitions with the program Poindexter had launched at the Pentagon, and they certainly had every reason to meet the man still regarded today as a kind of sacred totem in the field of mass electronic surveillance. Poindexter was interested in their proposals but ultimately concluded they lacked the necessary infrastructure. For this reason, he suggested they collaborate with one of the companies already working on the Total Information Awareness program. The two Palantir founders rejected the offer, because according to Poindexter, “they were so arrogant that they were convinced they could do everything on their own,” without any partnerships. Eventually, their trusted mentor Richard Perle guided them down a different path, and shortly thereafter Palantir would be established at the Pentagon under different terms.

Palantir’s original technology originates from a previous Thiel company, PayPal. In 2000, the payment company’s engineers developed a program that would indicate fraud through the PayPal network, but found that algorithms alone were insufficient to keep up with how quickly fraudsters were evolving their methods. The solution to the problem was a program named Igor, after the pseudonym of a notorious Russian hacker who had pierced PayPal’s security systems, which identified all suspicious transactions and flagged them for human operators to review.

In 2003, after the sale of PayPal, Thiel approached Alex Karp, his old Stanford classmate (and unrelated to computer science; his studies focused on neoclassical social theories) with the idea of adapting the Igor program to identify terrorist networks through their financial transactions. At that time, the CIA still had minimal experience or even interest in such an approach. Thiel was the one who put up the initial capital, and after they began seeking investors, Palantir secured its first solid foothold in the secret services universe with a $2 million investment from In-Q-Tel, the CIA’s investment firm. The CIA’s goal was to recruit the best available talent from Silicon Valley in order to successfully unify disparate and isolated sources of information into a single database, regardless of their type. Regarding In-Q-Tel’s investment, Richard Perle himself, that tireless supporter of Thiel and Karp, stated in an interview that “I have my doubts about the CIA, but this angelic investment [sic] in Palantir may be one of their most inspired moves.” With the In-Q-Tel investment, Palantir got off the ground, but this move provided something more important than money: the CIA’s protection. As doors began to open in Washington, Palantir started gaining more and more friends and access within various secret services and security agencies.

For three years, from 2005 to 2008, the CIA was Palantir’s sponsor, its only customer, and the final tester and evaluator of its programs. With the CIA’s help, the company began supplying software and training to army units destined to be deployed in Iraq and Afghanistan. However, the method it employed was not the standard one, but “sideways” and unusual. Instead of following the normal procedure and approaching the Pentagon through its relevant services, Palantir began supplying directly the combat units, thus creating demand for its services from within and securing at the same time a valuable base of already trained “consumers.” Gradually, Palantir gained footholds in the lower echelons of the hierarchy, until the commander of the occupation forces in southwestern Afghanistan personally requested to get in touch with Palantir. At that time, the army’s main data integration and processing program was the Distributed Common Ground System–Army, developed by the Pentagon’s traditional suppliers, with a cost exceeding 10 billion dollars. However, the problems of DCGS–A were its difficulty of use, especially by inexperienced users, its slow speed, and its frequent crashes.

This particular commander was impressed by Palantir’s program, especially the part dealing with the timely detection of improvised explosive devices, which was the main cause of deaths among occupying forces, and by securing some capital that was intended for other things, he awarded Palantir its first contract with the military. From the company’s side, an additional bonus was offered: along with the software, a team of the company’s engineers, the “forward-deployed engineers”, would be embedded in combat units in order to adapt the program on-site to the respective needs. It goes without saying that this commander, after his retirement, became a consultant at Palantir.

Palantir quickly began expanding into Afghanistan, both in the army and among special forces. But back at the Pentagon, the company’s practice reportedly caused a “headache”. The army’s designated service responsible for all procurement warned that Palantir’s tactic was not merely unusual and extrajudicial, but illegal, and that soldiers are forbidden from accepting training and electronic programs from external sources without oversight and approval. This sounds reasonable, so what was the Pentagon’s response? The issue was resolved by awarding Palantir a small contract, in order to cover and retroactively justify the provision of its “free” services.

Let’s sum it up: a company controlled by the CIA bypasses the entire military hierarchy and the official/legal procedures of the Pentagon, trains combat personnel, supplies them with programs used on the front lines, places its own people within combat units to control and adjust the program, and instead of the Pentagon kicking them out and dragging the responsible parties to court, it rewards them with a contract and acknowledges their role. Hollywood could certainly serve up this scenario with a thousand-and-two patriotic and superhero movies, but in the real world, only one interpretation makes sense. That this was a well-staged CIA operation aimed at installing Palantir in the military, with the cover-up and/or subsequent acknowledgment of the Pentagon. The reason why Palantir’s infiltration was orchestrated in this way likely lies in the realm of the secret. It may have had to do with overcoming bureaucratic obstacles or bypassing rival factions; perhaps direct CIA involvement would encounter resistance, or a scenario needed to be created that would justify Palantir’s profile as a “capable-of-everything” company. Most likely, Palantir was crafted as a vehicle or shell through which American intelligence services could step into fields otherwise forbidden. The facts, however, are two: first, it was an intelligence service maneuver, and second, Palantir is their showcase.

As Palantir was strengthening its relationships with the Pentagon, it began to operate with greater formality, following the well-trodden path of the army’s other major suppliers, hiring lobbyists and distributing money to the appropriate recipients in Washington, with the primary goal of discrediting the DCGS-A program and removing it from the picture. Note the name of the person who became a consultant for Palantir at that critical moment. Lieutenant General Michael Flynn, who subsequently took over as head of the army’s intelligence services, later became Trump’s first security advisor with a tenure of just 22 days (after resigning when it was proven that he had provided false information to congressional committees) and recently came back into the spotlight when his name was mentioned among those responsible for the invasion of the Capitol on January 6th and was one of those who advised Trump to proceed with extreme actions.

Techie Tailor Soldier Spy

With its base established at the Pentagon alongside the CIA, Palantir’s operations began to expand and multiply. Major contracts followed with the FBI, military intelligence services (Defense Intelligence Agency), the Department of Homeland Security, the NSA, and the Army Special Operations Command. Palantir’s software became the exclusive tool used by soldiers in Afghanistan to counter improvised explosive device attacks and predict upcoming insurgent assaults; it was used in operations against Mexican drug cartels; it even reached the court of the Dalai Lama to eliminate Chinese spyware installed on his computers and decrypted a massive volume of documents, shedding light on the intricate frauds of financier Madoff. Palantir collaborates closely with the American Customs and Border Protection (the militarized service that guards the borders) to identify migrants crossing the border, as well as with the notorious ICE (Immigration and Customs Enforcement) that hunts migrants within the borders. It is specifically this “collaboration” with ICE that has triggered the most reactions, as Palantir is rightfully considered responsible for breaking apart immigrant families, deporting parents, and imprisoning underage children in detention camps. Police services are certainly not absent, as Palantir has long been installed, among other places, in the police departments of New Orleans, Chicago, New York, and Los Angeles, which we will discuss in detail later. Finally, given the Palantir-CIA connection, it is worth noting that the client list formerly included the IAEA, the International Atomic Energy Agency, responsible for monitoring Iran’s and North Korea’s nuclear programs, for which Palantir provided its services free of charge.

In 2010, the New York Police Department introduced Palantir to JP Morgan, which became its first customer outside of government services. A decade later, the company operates in more than 150 countries (other sources put the number at 250), serving both the private and public sectors, including the United Kingdom and France with the most contracts, as well as Germany, Switzerland, Ireland, the Netherlands, Brazil, India, and Canada. Relations with Britain have been ongoing for years and include collaborations with GCHQ, the UK’s electronic surveillance and cyber defense agency, and the Ministry of Defence.

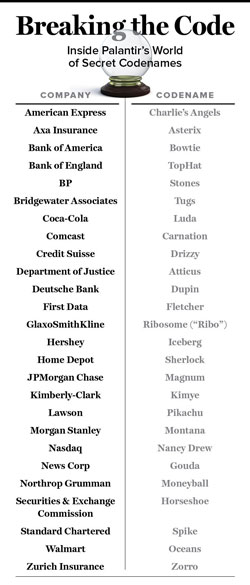

BP is currently Palantir’s largest customer, having signed contracts worth $1.2 billion over the next ten years. Other clients include Airbus, Credit Suisse, the Bank of England, Bridgewater Associates, Deutsche Bank, GlaxoSmithKline, Morgan Stanley, Ferrari, News Corp, and Northrop Grumman. One of its major business ventures was the formation of a data-sharing consortium that would include the largest consumer goods companies in the US. The goal was to merge the databases of all these companies in order to thoroughly analyze that specific market and public consumer behavior. Clearly, if completed, it would have been the largest database of its kind, under Palantir’s control. The heavyweight behind this project was Coca-Cola, which had agreed to a trial period but eventually abandoned it, citing “differences in mindset”; apparently, it was not ready to be handcuffed to the intelligence services’ wagon.

With the onset of the hygiene war, Palantir and its tools found themselves on the front line. In the US, the Department of Health collects and processes data from millions of Americans using Palantir’s technology. The digital platform Protect Now, which Palantir established and manages on behalf of the ministry, collects data from at least 187 different sources, including the federal government, state authorities, municipalities, hospitals and the private sector. In Britain, Palantir signed a contract with the NHS (national health system) in March 2020 to process data related to covid-19, for the consideration of only one (1) pound. The contract expired in June, but was extended for another four months at a cost of one million pounds, while negotiations have already begun for a five-year contract that will reach 100 million. We referred to the Greek case of import and it is not the only one. We have also identified the case of Colombia, which seems to share many things in common with Greece. In Colombia, the relevant news came to light in October, from a company blog and is almost identical to the Greek one: Since the beginning of the pandemic, Palantir has been working closely with the Colombian government… The Visor COVID-19 program is a digital tool built on Foundry on top of Amazon’s web services infrastructure and provides a unified, real-time picture of the pandemic situation… Never before had intelligence services shown such interest in public health and never before had the exploitation of personal data been so critical in dealing with a virus.

With such an inflationary business activity, with such powerful clients, with contracts in dozens of countries and an almost supernatural reputation for its capabilities and connections, Palantir should logically belong to the category of hi-tech companies whose profits are measured in hundreds of millions. And yet, reality shows a different picture, raising from this perspective, the economy, the question of whether it is a normal company or a smoke screen covering American secret services, the deep state and their actions.

After nearly two decades of activity, Palantir still hasn’t turned a profit, consistently reporting annual losses in the hundreds of millions. In 2019, despite a 25% increase in revenue to $740 million, it recorded losses of nearly $600 million, marking the second consecutive year with such losses. Amazon took eight years to become profitable, Netflix six, Facebook five, and Google three; Palantir has completed 18 years and remains unprofitable. Moreover, it keeps losing clients; just in the past year, three of its top clients abandoned it: Coca-Cola, American Express, and Nasdaq. One reason explaining this situation is Palantir’s idiosyncratic way of forming contracts in the private sector, in contrast to government services, where it ensures an almost exclusive partner status. In a presentation to potential investors, Palantir had described the contracts it offers as “variable and exotic.” They begin with a trial period that can even be at no cost (see the one-pound contract with the UK’s NHS), followed by a second phase where the cost may be tied to effectiveness as judged and decided by the client themselves, and ultimately requiring a long time before the contract begins generating real revenue for Palantir. Essentially, it loses money from its clients during the initial years of their collaboration. Karp himself, at a 2014 conference, had said that “some of our biggest jobs are with people who can barely afford to pay us. We have a bunch of clients from whom we make zero money.” Economically, this practice appears completely unsustainable and highly risky, unless Palantir’s goal is not to compete with industry giants in terms of profitability, but something else. If the actual goal is to plunder the accumulated digital wealth from the electronic vaults of its “clients” and to integrate scattered databases into a planetary-scale infrastructure under CIA control, then this “exotic and variable” practice is extremely effective—there’s no need for permanent client relationships, and to friendly parties, an alternative can be offered: a “real-time dashboard for monitoring Amazon’s web services infrastructure,” along with a few more covert digital manipulations.

A similar “peculiar” situation also prevails in Palantir’s relations with its staff—beyond the allergy to any publicity, the general ban on contacts with the press, or the use of secret codes when referring to clients. In recent years, Palantir has been losing its executives at a rate that started at 10% and gradually increased last year to 20%. When putting together departures with corresponding hires, Palantir has an unusually high staff renewal rate for a hi-tech company, while its competitors engage in head-hunting to secure talented engineers for their stables. Unproductive at the very least, unless what runs through Palantir is not only “work,” but also seminars, possibly combined with psychological tests and indoctrination. Ten years ago, the NSA suffered a major blow when one of “its own,” Edward Snowden, was horrified by the big-brother surveillance exercised by the agency and spilled everything out in the open. It would be unacceptable for such a failure to be repeated; therefore, somewhere these future forward-deployed engineers must be “trained.” How much of a “company” is Palantir, ultimately?

The besieging ram of secret services

We have already noted that, due to the nature of Palantir’s activities, few specific details exist regarding its current operations. What has come to light has arisen either from internal leaks, or from the persistent work of suspicious researchers who have managed to combine fragments of information, or because rival services have gotten their hands on them. We will refer here to three cases, indicative of the kind of services it provides: the first concerns Palantir’s involvement in the Cambridge Analytica affair and the 2016 U.S. elections (you can read more in Cyborg #12, internal cyber psyops of the 4th world war); the second concerns Palantir’s infiltration into international humanitarian organizations; and the third concerns the extensive surveillance mechanism established by the LAPD with Palantir’s assistance.

American elections 2016

While in the US and much of the Western world Trump’s 2016 victory was seen more or less as a dark conspiracy with Moscow as the main protagonist, allegedly mobilizing every available mechanism to promote its chosen candidate to the White House, in Russia they conducted their own analyses to explain the impressive victory of an orange, unpolished fascist in the “strongest democracy.”

The name Elena Larina probably means absolutely nothing to you, but in Russia she is considered an analyst whose opinion matters and moreover a Kremlin insider; therefore those who read her know that she echoes the views of the central mechanisms. She is a businesswoman, author, criminologist, regular contributor to state media, editor of a blog with analyses and periodically has served as special advisor to the Russian Ministry of Internal Affairs.

After the American elections she published online her own analysis of Trump campaign’s pre-election strategy and according to this, Trump’s son-in-law Jared Kushner, his fascist advisor Stephen Bannon and Palantir founder Peter Thiel, equipped the campaign staff with highly accurate analyses of voter trends. These analyses were products of cutting-edge technologies from three companies: Cambridge Analytica, Palantir and Quid (in which Thiel is also a co-founder and one of the initial investors). Larina’s view was that data mined by Palantir was formatted by Quid and subsequently transferred to Cambridge Analytica to be “translated” into specific pre-election operations.

According to the analysis “for Trump to evolve from a joke to a black swan, Bannon and Thiel used Palantir to identify the non-normal states. Palantir concluded that 11 states were ideal for targeting, particularly five that traditionally were Democratic strongholds, in which Palantir’s analysis showed abnormal trends. The data then passed to Quid, which has a holistic view, treating data as communities of organisms. Quid primarily analyzes language on the internet, searching for anomalies and hidden trends on behalf of electoral campaigns as well as private sector businesses. Quid looks for those points where even relatively small pressure can cause major ruptures. Quid had predicted that Michigan, Wisconsin, Iowa, Ohio, Pennsylvania and Florida had the dynamics to deliver the desired result.”

Larina’s analysis was published in two consecutive issues under the title “Trump’s Revolution” in the geopolitical analysis journal of the Izborsk organization (one of Russia’s major think tanks) and was republished hundreds of times across the Russian-speaking internet, especially after it was adopted and promoted by Oleg Matveychev, a Russian politician, governor of various regions, and Kremlin public relations consultant; in this way, it acquired almost semi-official status. Therefore, beyond the data it presents, which can be judged for their accuracy or not, what matters is the fact that the Russian side chooses to focus on and highlight precisely these three companies: the well-known Cambridge Analytica, involved in this case, as well as the “related” firms Quid and Palantir.

Spies Without Borders?

The organization The New Humanitarian is not at all disconnected from the world of humanitarian operations, quite the opposite. It was founded by the UN in 1995 as IRIN, after the genocide in Rwanda, when it was deemed necessary to establish a specialized news agency focused on on-the-ground reporting of humanitarian crises. In 2015, IRIN decided to detach itself from the UN and transform into an independent non-profit news organization (and also changed its name to New Humanitarian), with the main goal of critically examining and monitoring the actions of relevant organizations and the multi-billion-dollar humanitarian aid industry.

In 2016, IRIN’s researchers discovered something alarming: that a large number of humanitarian organizations were turning to the digital services of a specific company, Palantir, which was known for its ties to intelligence agencies. We republish a few characteristic excerpts from the relevant investigation:

A month-long investigation by IRIN into the company Palantir, which is linked to secret services, reveals warm relations with many humanitarian organizations, both large and small, reaching as far as the services of the UN itself and involvement in the international response to the Ebola epidemic. But how close are these relationships? […]

The digital tools developed by the secretive Silicon Valley representative of Palantir can be used for a wide range of humanitarian issues: from human trafficking and arms smuggling to responding to natural disasters; they can bring revolution to coordination, management, and crisis response.

But the international humanitarian community is uneasy. Palantir maintains exceptionally close ties with the American secret service establishment, and the boundary between political intervention and humanitarian action is constantly under attack to the detriment of the latter. […]

Palantir’s ability to process and analyze data is already being used by prominent American humanitarian organizations such as the Carter Center, the Clinton Foundation, the Rockefeller Foundation, and the anti-money laundering organization Enough Project.The UN agency that monitors nuclear activities, the International Atomic Energy Agency, has also hired Palantir. The IAEA has a mission to verify the implementation of restriction agreements—with Iran and North Korea, for example—and spent $500,000 in 2014 to procure Palantir’s Gotham program to analyze the relevant data. […]

It seems like a direct blow to humanitarian principles, if not common sense, for humanitarian organizations to seek collaboration with an entity whose roots are so deeply embedded in covert operations.

There are many places on the planet where displaying a Palantir logo on your laptop isn’t particularly smart. And there is significant, if not reflexive, concern that having Palantir at your feet is an open invitation for the American NSA to read your emails, collect your data, and add it to their massive, planetary, espionage haul.

Palantir claims there are no hidden connections and that contracts include terms clarifying that data will not be shared with secret services. But humanitarian operations advisor Paul Currion has fundamental concerns. “Technology is often considered neutral and is marketed to us as such. But the reality is that software programs have specific specifications embedded in their code. The specifications of secret services have nothing to do with our own. Software built for their purposes is not going to serve us, even if it is effective software.” […]The humanitarian action, or as Palantir calls it “philanthropic engineering”, looks like the company’s voluntary contribution, whose value is estimated at 20 billion dollars. It makes its money by selling licenses for its programs, all of which are cutting-edge technology, but the real profit lies in the highly skilled personnel that Palantir deploys to run the system on your behalf – the “forward-deployed engineers” as they are called in the company’s military terminology.

According to market specialists, a “bare” system at commercial prices would cost at least 7 million dollars per year; together with all the accompanying services, the cost easily reaches 12-15 million – although the price depends on scale and customization. Nevertheless, the company offers its services to humanitarian organizations practically free of charge. In the case of the proposed collaboration with the UN’s emergency response coordination service, OCHA, and later with the UN’s Ebola mission, Palantir offered such large discounts that the contracts would have had difficulty passing through the OHE’s legal services.Palantir’s initial interest in the non-profit world seems to have more to do with seeking a new business model than with altruism. Direct Relief was one of Palantir’s first partners, and its director describes a scenario according to which, before the rise of the so-called Islamic State, counter-terrorism as an area of activity appeared to be in decline and did not offer the same opportunities as today. «I can understand in hindsight that we were a kind of pilot project» and they knew that Palantir essentially «paid customers» to gain access to the humanitarian aid sector.

Although company employees claim they have no concerns regarding connections with intelligence services, many OCHA officials confirm that it was precisely these fears that ultimately led the agreement to shipwreck. “OCHA donors would be very cautious and reserved about how we work with them.” “I’m sure their idea [Palantir’s] was to become the central information service for the entire humanitarian community. But if that was their goal, then they’re not on the right track. They rather underestimated how paranoid we are about the dark side.”

Burn, baby burn: LAPD case

The Los Angeles Police Department (L.A. police department) is one of the oldest and largest customers of Palantir, and thanks to its tools, the police have managed to set up one of the largest and most powerful surveillance and monitoring networks throughout the state of California. The main program used by the LAPD is Gotham, a software that promises “to bring clarity and order where every other technological infrastructure has failed.” But to function, it needs data, abundant data.

A large portion of the data that the LAPD has at its disposal consists of the names of people who have been arrested, tried, convicted, or even just deemed suspicious, but this material is only the beginning of the surveillance network. Palantir processes the derivatives of daily police activity, regardless of their significance, form, or cleanliness. A police officer may have been told that someone knows a gang member; someone else may have spoken to a neighbor at a crime scene or to someone who was simply passing by; a patrol car may have taken a photograph of some faces next to a specific car; anything. The content does not matter. Once the LAPD adds any piece of information concerning a person to its Palantir database, that person becomes a node in an extensive police surveillance network. Palantir has enabled the LAPD to build a monstrous database that indiscriminately includes lists of names, addresses, phone numbers, employment statuses, license plates, friendships, family relationships, and any other available information about the residents of Los Angeles—innocent, guilty, suspects, and anyone in between.

The Palantir database also includes all data from the DMV (the department that issues driver’s licenses and license plates), which means that anyone with a California driver’s license is de facto registered in the LAPD’s surveillance network. It also includes over one billion photographs of license plates taken at traffic lights and toll stations in Los Angeles and surrounding areas. This means that if someone has driven in Los Angeles after 2015, the police can instantly determine where the car was photographed, which routes it took, identify the driver, and within seconds obtain exhaustive details about their life.

Palantir has effectively become a second police force within the police. Approximately 5,000 officers, more than half of the LAPD’s personnel, have accounts on Palantir and directly use its tools. In 2016 alone, there were over 60,000 searches in the database for more than 10,000 different cases. Outside Los Angeles, dozens of police departments throughout California, airport police, university police, and school security services have signed agreements to share all the data they possess with the LAPD. Furthermore, all these services must daily send all their activity data (warrants, arrests, reports, license plate recordings…) to the LAPD so that it can be entered into Palantir.

With Palantir’s tools, police can search for someone based on any of their details: name, race, gender, gang involvement, job, tattoos, marks, friends, or family. The search is done in an extremely simple way, such as “male, white, Peckerwood gang, skull tattoo,” and the engine will return a list of names, addresses, vehicles, email addresses, warrants, booking records, and anything else that has ever been recorded for any reason. If the engine also finds relevant photographs from surveillance cameras, it will also “serve” those along with every interpersonal relationship it infers—friends, relatives, neighbors, colleagues… LAPD can then use this data in a specific case or create lists of individuals whom the system considers likely to commit a crime in the future; a Minority Report dystopia with somewhat less futurism.

The first time this surveillance and monitoring network came to light was in 2010, and it happened almost by chance, when an activist, a resident of a Los Angeles suburb, learned incidentally that the local police department had started an automated program to photograph all license plates encountered by patrol cars on their routes. Following legal procedures, he requested the authorities to provide him with every photograph concerning himself, his family, and his residence, and the police handed over 112 photographs, which, if arranged chronologically, created a rough picture of his and his family’s daily life over a long period. Digging deeper, he discovered that millions of photographs automatically taken by all patrol cars are collected at the Northern California Regional Intelligence Center, one of the 72 federal surveillance agencies established after 9/11. And from there, they end up – no question needed – in Palantir’s database.

Andrew Ferguson, law professor, author of the book The Rise of Big Data Policing and researcher of the LAPD-Palantir relationship, has argued that data-driven policing has nothing to do with collecting data about crimes. It means that the basic job of police is now increasingly to intensify surveillance in order to collect more and more data. “Palantir’s systems are exclusively aimed at surveillance… Palantir’s job is to help police monitor and surveil more and more people. And by definition this system is ever-expanding. It’s a platform that can incorporate data from any source and turn it into material for a surveillance and monitoring network.” And that’s exactly what Palantir did for the LAPD. It integrated and unified the contents of dozens of databases that were previously scattered across various public services throughout Los Angeles and California – including recent additions such as data from public health services – thus constructing the largest operational Panopticon.

The spy who returned from cyberspace

“Palantir is a company defined by its purpose, and I have specified what that purpose is. The necessity to combat terrorism.”

“Our company was founded in Silicon Valley. But it seems we share fewer and fewer values and commitments with the technology sector. The engineering elite of Silicon Valley may know much more than any of us about building software. But they know nothing about how a society should be organized or what kind of justice it requires.”

“We have chosen a side, and we know that our partners value our dedication. We stand by them when it’s convenient, but also when it isn’t.”

“The essential mission of our company has always been to make the West, especially America, the strongest in the world, the strongest that has ever existed.”

All of the above stem from statements and texts by the two founders of Palantir, and anyone who understands what they are reading should realize that these declarations do not correspond to a typical company, but to a special operations business unit. Palantir does not conduct business; it is on a special mission ordered by American intelligence services. If we look at the story in reverse, our conclusions will still hold: let us assume that the CIA and NSA, along with the entire network of American intelligence services, wanted in the name of the total information awareness goal to organize a data harvesting operation on a global scale, in order to establish a monstrous surveillance and control network. What operational structure would they choose? Surely they would not undertake it directly themselves, because in case of exposure the reactions would be enormous even within the United States; for Google or Facebook to plunder personal data is now considered something like a seasonal phenomenon, natural, whereas if a secret service does it, it can still be provocative.

In what way could this nexus erode organizations, infiltrate services, seize the accumulated digital wealth on a planetary scale and moreover do so effectively, without coordination problems, internal competition and bureaucratic or political obstacles, unchecked and without limitations? By creating for them a palantir. A former “start-up” and now a company valued at 22 billion dollars, a diamond in the crown of Silicon Valley, is allowed to access the databases of market mammoth companies; if the CIA did it, it would at least be clumsy. Palantir has the ability to offer attractive “contracts” in the name of the free market and infiltrate the services of other states; when the CIA did this it was the 1960s and it was called a coup. No Western society is going to rise up because another tech giant has come to skim their personal data; however, some will be disturbed if they learn that the NSA wants their data because we are at war.

Palantir arose naturally as the technological extension of secret services in wartime conditions and is not going to be temporary, unless the excessive noise around its name makes its mission problematic. How much more so now, when panic, the “war against the virus” and sanitary coups have paralyzed criticism, blocked reactions and have dissolved any restrictions. In Greece, and not only, Palantir came to “offer data-driven answers” in times of crisis and it is most likely that in the one year it has been here it has already harvested the data it wants; it is now too late. But let us at least keep this in mind: that our world is becoming faster and more transparent and permeable. Like a huge glass algorithmic prison…

Hurry Tuttle