We owe Alex Carey1 the following accurate observation. We tend to think that the most totalitarian regimes are those that make the most systematic use of propaganda and psychological warfare methods. In practice, however, the exact opposite is true. It is the liberal democracies that have the greatest need for propaganda mechanisms – indeed refining them to the highest degree – precisely because they do not have the luxury of resorting so frequently to the use of direct violence. The drive to exercise physical violence, which is constitutionally inscribed in the internal logic of every class-stratified society, appears to be transmuted in the liberal, mass “democracies” of the 20th and 21st centuries into an uncontrollable tendency toward psychological violence and information warfare. Whatever cannot be achieved by tear gas, gun barrels and battle tanks is accomplished primarily by newspapers, radios and televisions; and secondarily, in a more covert way, by the industry of mass entertainment (primarily musical and cinematic).

In the not-so-distant past, the above observations would be accepted, more or less unquestioningly, by any seriously thinking person, regardless of their position on the political spectrum. Even a conservative with basic intellectual integrity would have no difficulty accepting that the role of mass culture and mass media converges on the pacification and domestication of the masses, acknowledging that this constitutes a necessary evil in order to ensure that “the masses can be governed.” A stance of accepting liberal platitudes about the democratic nature of institutions and genuinely believing in them was a safe sign of harmless naivety, unless there were self-serving motives behind it. Especially for those who identified as left-wing, exposing the manipulative role of the media was one of their main duties, even if this remained largely at a highly abstract and “philosophical” level, rarely touching upon specific and actual interests. For a while, Chomsky, through his relevant analyses of propaganda mechanisms, became a minor star and almost mandatory reading for every leftist.2 However, those same leftists who once swore by (any version of) Chomsky may now rejoice when major U.S. television networks cut off Trump’s speeches mid-air, or when the otherwise “multifaceted” social media platforms suspend his account, effectively imposing a kind of censorship. It seems overly difficult for them to understand that Trump is simply a political front for certain factions of American capital and that he is the most prominent victim of an information war in which other segments of the American elites—those with deeper (or even direct) access to propaganda mechanisms—are also participating.3

If therefore the covid era is indeed an era of war, as states, governments and pharmaceutical-biotech industries assure us, then the well-known axiom that the first victim of every war is truth should also find application here. The important question however in this case concerns the identity of the victim. Is truth and social order threatened by vulnerable and poorly equipped groups of “paranoid covid deniers”, as it seems to be believed by opportunistic and mediocre journalists, intellectuals and academics whose middle-class comfort has degenerated them into a kind of intellectually undead vampires (while remaining otherwise fiery “revolutionaries”), and by all kinds of well-funded expert researchers? Against whom has the entire propaganda mega-machine been directed all this time, and who are facing persecution (so far only at the level of censorship, perhaps legal in the near future)? How plausible is the claim that all this modern holy inquisition of the 21st century is driven by humanitarian feelings of protecting population health rather than by needs of biopolitical management of them?

Bombs in the mind: the category of conspiracy theories

Paranoid ideas that attempt to explain complex phenomena in a simplistic manner have been circulating within human societies for millennia. Very often, they not only circulate but are moreover elevated to official doctrines. The highly popular idea, especially in Western, “rational” societies, that a benevolent being created the world out of pure love does not merely enjoy majority acceptance; in certain states, such as Greece, it constitutes an organic part of national ideology and mythology, often functioning as a pretext for large-scale crimes. Critical thinking has found itself many times on the front lines against such perceptions, especially since the source of their origin can almost always be clearly traced to methods of the ruling powers, if not directly, certainly indirectly – even when not directly produced by propaganda mechanisms, the soil of economic, social, and intellectual degradation in which large segments of populations are pushed is so fertile that the seeds of paranoia sprout with minimal care and grow like weeds. Yet, no special terminology was ever mobilized; one could speak of religiosity, of a tendency toward metaphysics, of idealism (a favorite accusation launched by orthodox communists), or of crude materialism (a frequent response from more deviant Marxists). In any case, someone had to explain why they used such a category or at least appear to try to offer an explanation, even if rough and approximate.

All this until recently. The latest trend among those who consider themselves intellectually sophisticated is to hurl the accusation of “conspiracy theorizing” not only at those who actually believe in coronavirus-related conspiracy theories, but also at those who dare to express reservations and maintain a critical stance regarding its management. This complex of intellectual superiority, however, when examined more deeply, conceals at least one (perhaps forgivable) historical ignorance regarding the origin of the “conspiracy theorist” label, but also an (inexcusable) willful blindness to the fact that it is precisely states, with their propaganda mechanisms, that systematically employ this accusation; a willful blindness that may ultimately indicate a desire to identify with mechanisms of power in an era when those who are or appear powerless are threatened with social, emotional, or even biological annihilation.

What however is really the origin of the term “conspiracy theory”? The bible of political correctness called wikipedia is not particularly enlightening. However it contains an interesting excerpt:4

“The term ‘conspiracy theory’ itself constitutes the subject of a conspiracy theory, which claims that the term became popular following efforts by the CIA to discredit and ridicule those who believed in some conspiracy [note: regarding the assassination of President Kennedy] and particularly those who criticized the findings of the Warren Commission [note: the official commission established to investigate the circumstances of Kennedy’s assassination]. Lance deHaven-Smith, a political scientist who in 2013 published the book Conspiracy Theory in America, supported the view that the term began to circulate widely in the U.S. after 1964, the year the Warren Commission published its findings, with the New York Times publishing five articles that year containing the term. However, this view of deHaven-Smith has been criticized by Michael Butter, professor of American philology at the University of Tübingen, according to whom the CIA document cited by deHaven-Smith titled Concerning Criticism of the Warren Report [Regarding Criticisms Against the Warren Report]—which was published in 1976 following a request based on the Freedom of Information Act—does not contain the phrase ‘conspiracy theory’ in the singular and refers to the term ‘conspiracy theories’ only once, in the sentence ‘Conspiracy theories have often placed our organization in the crosshairs of suspicion, e.g., wrongly accusing us of Lee Harvey Oswald working for us.'”

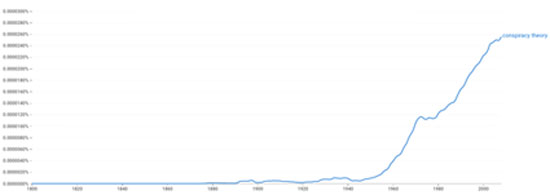

Butter’s article can easily be found on the internet.5 There we learn that, contrary to what deHaven-Smith claims “conspiratorially,” the term “conspiracy theory” was already in circulation from the late 19th century. Therefore, the authors of the CIA document were simply adopting and using a term that was already established, and they did nothing suspicious nor attempted to use the term as a tool of defamation. For the sake of truth, the diagram below depicts the frequency of the term’s usage in books that have been digitized and catalogued by Google:

The issue can therefore be considered closed. Another fantastic conspiracy theory. But is it really? The diagram clearly shows a trend of the term’s usage skyrocketing after 1950, and even more specifically after 1960, which should already create some initial doubts as to how established the term was in 1964. Beyond simply looking at this diagram and drawing easy conclusions, one can delve deeper and see exactly how this term was used each year. In the 19th century, the term does indeed appear in various texts; with the significant difference (which one can observe by focusing on specific years) that it had an entirely different meaning. It usually appears in legal texts, where the term “conspiracy” refers to the commission of the eponymous crime. Even in 1960, it is not found with its dismissive connotation (in the samples we examined), although it sometimes acquires additional meanings. As “conspiracy theory,” it may refer even in academic texts to the Marxist conception of history, meaning that it is a view of history that leaves little room for the factor of chance and the unpredictable, yet this characterization of the Marxist view is not intended disparagingly. It functions more descriptively, possibly implying a drawback of this conception, which however remains a legitimate subject of academic discussion. If one focuses on 1964, one will indeed see the term appearing with its current meaning, for example, in texts referring to theories that claim that behind the Black Panther movement lies a Soviet finger—New York Times archives also show the term appearing in articles from 1964 referring to the Warren Commission report.6

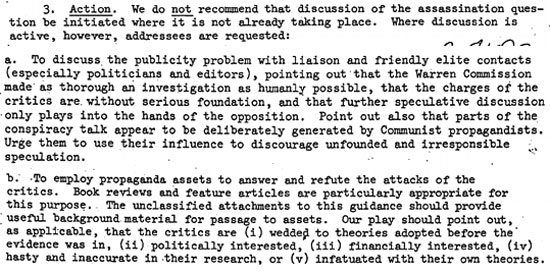

The situation becomes even more alarming if one takes the trouble to read the CIA document itself. It should be noted here that this particular document was not addressed to the general public but internally, to agents of the service, providing them with instructions on how they should respond to any criticism. We then present an indicative excerpt:

And its translation:

“Action: We do not recommend initiating discussions regarding the assassination issue when such discussions are not already taking place. However, where such discussion exists and you are addressed, you should:

a. Discuss the publicity issue with friendly high-level contacts (especially politicians and editors), emphasizing that the Warren Commission conducted the most thorough investigation humanly possible, that critics’ allegations lack basis, and that any further speculative discussion only serves to feed the opposition. It should also be emphasized that part of this conspiratorial talk appears to deliberately originate from communist propagandists. Encourage them to use their influence to discourage unfounded and irresponsible speculation.

b. Use propaganda assets [note: a term difficult to translate literally in Greek, referring generally to people useful to a service but not directly belonging to it] to respond to and refute critics. For this purpose, book reviews and articles on the subject are particularly appropriate. The unclassified documents accompanying this guide provide useful material that could be conveyed to the assets. Our [original: play] stance should emphasize, where possible, that critics are i) devoted to theories they have accepted without seeing all available evidence, ii) have political interests, iii) have economic interests, iv) have conducted hasty research with inaccuracies, and v) are deluded by their own theories.”

The entire document moves along the same line, advising CIA agents on how they can undermine the credibility of their opponents. It is more than obvious that it matters little that the term “conspiracy theories” appears only once. The term “conspiracy” is continually referred to, either directly as is, or periphrastically (“wedded to theories before the evidence was in”, “infatuated with their own theories”) and clearly with a disparaging disposition, without reference to actual facts. The aforementioned data therefore align with deHaven-Smith’s hypothesis that the term “conspiracy theories” began to spread through this document, although indeed such a hypothesis is difficult to prove.7 What is certain is that this was not some innocent use of the terminology regarding “conspiracy theorizing”; even if the CIA was not the first to use this particular terminology with a derogatory disposition, it was certainly among the pioneers, since until then its context was completely different and its common usage did not refer to paranoid delusions. The use of the term was clearly hostile and within the framework of propaganda.

This phenomenon, whereby various self-appointed defenders of the right cause, in their battle against those they consider to be obscurantists and conspiracy theorists, ultimately prove to be very few upon closer examination of their arguments, is not uncommon.8 Those accused of conspiracy theorizing often possess much more coherent thinking and solid background compared to the “rationalist” defenders of political correctness. The category of conspiracy theorizing thus appears to be essentially devoid of substantive content—a void which the current sovereign naturally rushes to fill as they see fit, much like how the category of “subversive action” was once mobilized against allegedly leftist circles to justify purges, or more recently, the category of “terrorism,” which proved so useful for the West in constructing the Islamic Other. A kind of (psycho-)medicalization of public discourse, in which the opponent is swiftly marginalized as incapable of rational thought and excluded from the realm of proper reasoning, traverses once again the well-trodden yet internally contradictory path of constructing the enemy as unworthy of attention by ascribing monstrous characteristics to them.9 This is an enemy who is dangerous (otherwise we wouldn’t bother with them at all), but this very dangerousness is exorcised by essentially erasing them from our intellectual field of vision. This terrifying yet ultimately very small opponent is, in the end, a phantom, a spectral being we construct precisely so that we may demolish and burn it with an almost sacrificial fury.

Karl Popper, known for his liberal naiveties, was among the first to teach, when in his book The Open Society and Its Enemies (1945) he argued against those who believed that there are powerful individuals and groups of individuals with the power to influence and direct the movement of society. According to Popper, (right and left) totalitarianism was nourished by such conspiratorial perceptions. A few years later (1964), historian Richard Hofstadter would repeat the same endeavor of defending liberal values with a (supposedly weighty) essay entitled The paranoid style in American politics. In both cases we are dealing with a project of demarcating the political center through the exile of the “extremes” to ideological deserts as (almost medically) incapable of participating in the liberal paradise; except that in those days the real opponent was naturally located at the left extreme, beyond even the limits set by the official left parties – the fact that today’s followers of far-left parties and grouplets seem to adopt tactics that were used against their ancestors is indicative in itself of where they actually stand politically: they wear the lion’s skin of a revolutionary verbalism to hide their deep conservatism. What both Popper and Hofstadter neglected to note is that liberal societies themselves generate that schizophrenic situation where in the first place they create an inflation of meanings (in the consumer logic that all truths are allowed, ergo there is no one truth) only to come in a second phase the propaganda mechanisms, when they deem it necessary, to offer binding truths, deciding in states of exception what is “logical” and what is “illogical” and dangerous for public order; something that in turn sets in motion successive additional cycles of paranoia, since this systematically undermines whatever faith in the good will of the propaganda media and enhances suspicion. They thus resemble drug dealers whose very use of their product creates the need for it. Except that in this case the psycho-emotional and intellectual addiction is sold by as it should be and reputable merchants of ideas and spectacles.

The propaganda machine: psychological warfare units

The entire discussion about conspiracy theories does not therefore arise from an innocent, academic interest in phenomena of mass intellectual degeneration and the misguided application of the principles of sound reasoning. It is organically embedded within the methodologies of propaganda mechanisms. The actual existence of groups with beliefs deemed to lack any rational basis is of little significance here. The fundamental function of the category of conspiracy theories is to strip those who are targeted by it of their essence as beings capable of participating in public discourse, to de-socialize them, to de-politicize them, and ultimately to delegitimize them both symbolically and literally: to push them outside the law and to construct them as criminals.

Of course, this is not a novel phenomenon in its basic outlines. Christianity had assigned the clergy for centuries the role of safeguarding the ideological order and constructing the “paranoid” and heretics. The bourgeois class, for its part, could ally itself with the clergy whenever this was deemed necessary for its interests (despite the occasional harsh rhetorical attacks against it); however, it did not place the clergy at the center of its strategy for ideological hegemony. On the contrary, it constructed and invested with authority a new specialized class, that of intellectuals, especially in the form of university professors and more specifically in that of scientists. The 19th century, the golden age of the bourgeois class, saw the university philosopher-scientist take on an almost priestly form,10 where, of course, his role was not simply the impartial search for truth. The following excerpt from Gramsci is accurate in its brevity:11

“The intellectuals are the ’employees’ of the dominant group, for the exercise of the dependent functions of social hegemony and political administration, that is: 1) The spontaneous consent of the great masses of the population to the guidance of social life by the basic dominant group, a consent that is historically generated by the prestige (and consequently also by the trust) that the position and mission of the dominant group in the world of production confer upon it. 2) The mechanism of state violence, which ensures in a ‘legitimate way’ the discipline of groups that neither actively nor passively ‘consent’, a mechanism created for the whole of society with provision for the period of crises in administration and leadership, when, that is, spontaneous consent becomes scarce.”

The role of intellectuals has not, of course, changed in the meantime – only intellectuals would believe such a thing.12 However, the traditional figure of the highly educated intellectual now typically addresses an equally more “refined,” middle-class audience. The second wave of ideological warfare consists of the clearly more numerous groups of journalists, advertisers, and entertainers of all kinds. There are two (at least) factors that drove this internal split within the class of intellectuals and led to the emergence of mass propaganda mechanisms in the early 20th century.

First, since the prerequisite for the existence of a special layer tasked with maintaining ideological order is the social and economic separation of mental and manual labor (so that some can “think,” others must sustain them), any change in the way this separation occurs is expected to bring about changes in the composition of the ideological police force. Such a thing happened exactly in the early 20th century with the introduction of mass production methods and the emergence of mass consumption behaviors. On one hand, the gap between intellectual and manual labor deepened even further; on the other, whatever free time existed was seen as fertile ground for commercial exploitation. The traditional layer of intellectuals, with their lofty pursuits, could not meet the needs of entertaining and amusing the citizens of mass democracies. It too had to undergo a split and a division of labor. Thus was established and expanded—the sector of public relations, with advertising and journalism serving as its two complementary arms—starting from cases like Ivy Lee, Edward Bernays, and Walter Lippmann13. Walter Lippmann, himself a journalist, would go on to speak in his book Public Opinion (1922) about the pseudo-environment in which every person lives, initially meaning the subjective way each individual perceives reality. His choice to use a new term (“pseudo-environment”) also signified something more: that this multiplicity of voices was potentially dangerous, since belief in a pseudo-environment could easily drive someone to irrational acts. Therefore, “the adjustment of man to his environment” should be achieved by employing “the medium of fictions.” And this must be done on a mass scale.

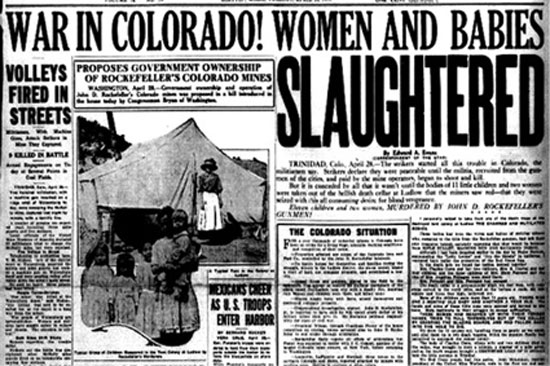

The second factor behind the birth of mass propaganda has to do with the political climate of the time. During the period around World War I (before, during, and after), massive waves of harsh labor strikes and resistances erupted both in Europe and America. The response of employers and states was often open and brutal violence. The massacre in the town of Ludlow, Colorado, in the U.S.A. is considered a pivotal point in the history of the American working class. Workers in the town’s mines went on wild strikes in 1914, only to face the American National Guard, which slaughtered them, killing 21 people, including women and children who were burned alive inside their tents. Employers, of course, had no moral problem with these killings per se; their problem was different: public opinion often sided with the strikers, especially when such brutality was exposed to the public eye. To reverse this climate, they turned to the new specialists in public relations at the time. Rockefeller, the owner of the Ludlow mines, was among the first to make use of the capabilities offered by mass media propaganda and their handlers. To improve his image in the face of American “public opinion,” he hired Ivy Lee and engaged in a series of advertising tricks that ultimately proved successful (in propaganda terms). If the movements of that time were defeated, it was not only due to the fierce repression they suffered, but also to the silence that covered up that repression—a silence carefully and systematically woven by propaganda and public relations mechanisms.

Today, after nearly a century of mass democracy, which brought about the collapse of classical bourgeois culture that allowed a degree of autonomy to intellectuals, a reverse trend is observed toward bridging the gap between high and low culture (or perhaps it is simply the disappearance of high culture). Only now it happens on the terms imposed by the propaganda machine, as it has gone through a phase of capital concentration (economic, but also symbolic, especially with social networks) and has grown to a suffocating degree for anything that refuses to pass through its gears. The intellectual, in order to exist as such, becomes a mere spectator and appendage of propaganda mechanisms, a ruminant of state and corporate fetishes which he chews over to serve them with a more refined flavor. His reward: a few likes, a few shares, and some status that may translate, at some level, into a privileged position. In its most shameless form, this type of intellectual-celebrity has a more specific name: that of the specialized scientist who (pretends to) always speak(s) on the basis of “hard” and “objective” data.

The propaganda machine: the rise of technocrats

In 1957, amid widespread concerns and reservations regarding the use of nuclear energy, the (now infamous) World Health Organization convened a study group to examine the issue, comprised of academics, psychiatrists, representatives of the American Atomic Energy Commission, and members of the European nuclear industry. The experts’ conclusion was that the public’s fears were “unreasonable” and “unfounded”:14

“Even if all objective data is interpreted in the most pessimistic way, the weight of available evidence does not justify any concern for the present, except perhaps for the very distant future. Yet, such concern exists and persists to an excessive degree. It is something that cannot be explained except by exploring the psychological nature of people themselves.”

Distrust towards advertisers and journalists has now become an endemic phenomenon in Western societies; it is a distrust that is absolutely justified, even if it does not always translate into a consistent and solid political stance of rejecting advertising and journalistic products. However, when it comes to all kinds of experts, this instinctive suspicion seems to be disarmed, even when they make monstrous “mistakes” that could cost lives. It’s always due to insufficient data, a methodological oversight, or equipment failure. The experts remain unscathed.

Although critiques of scientific reason flourished briefly in the 1960s, from the 1980s onwards the technosciences took their revenge by triumphantly advancing (reheated) promises of continuous progress through technology. However, the rise of experts was not a spontaneous social process; to a large extent, it was planned, once again as a reactionary movement against the movements of the 1960s and 1970s and the subsequent alleged “governance crisis” of Western societies.15 Experts and technocrats came to the forefront as the most suitable to confine the boundaries of public discourse within acceptable frameworks, aided also by the extraordinarily high level of specialization in scientific research.

How, however, is it possible for scientific knowledge to be used for essentially propagandistic purposes? Aren’t scientific truths supposed to be immutable and scientists impartial (as humanly possible) researchers? The answer to such a question is not simple; and certainly does not boil down to a simplistic affirmation. Yet examining this question, even superficially, becomes an urgent necessity in an era where technoscientists and politicians tend toward a dangerous identification, with the former hiding behind the latter and vice versa, in a cycle of mutual reinforcement and glorification by the mass media.

What must first and foremost be understood is that scientific truths are social products, and their mode of production is also thoroughly social. There is no automatic, “objective” mechanism for producing them that transcends human passions. A scientist, in order to become and be recognized as such by peers, must pass through multiple and successive filters that ultimately determine what they will work on, which theories they will follow, and which methodologies they will employ. At one end of the spectrum, the simplest case of filtering is the ostracism of a scientist due to direct political or business interventions in their research field when their findings are not those desired by their superiors or employers. Without the percentage of such cases being negligible,16 this remains rather the crudest and most unrefined method of filtering scientific truths.

On the other hand, the most complex, invisible, and therefore almost universally present filtering method relates to the well-known phenomenon (from the studies of Foucault, Kuhn, Feyerabend, Blumer, and other radical epistemologists) of scientists being immersed in a given universe of concepts and methods inherited from previous generations of their colleagues—what Kuhn called a paradigm—and which they themselves typically receive uncritically, without much inclination to question it. The conceptual constructions that constitute any epistemological paradigm cannot, however, be explained simply by appealing to the demands of a narrowly defined empirical and positivist rationality; their references also point to extra-scientific pressures, such as those arising from the intersection of economic, political, and ideological forces in motion within a given social climate.17 The process of a scientist’s initiation necessarily includes accepting the currently dominant paradigm; the pharmaceutical industry and the entire medical circuit would be unable to function if medical specialists did not share the perception (epistemological paradigm) that the body is a mechanism whose flows must be regulated from outside through drugs.

The scale of filtering scientific truths and facts includes several additional intermediate steps of retaining “undesirable” or simply incompatible theories and ideas with prevailing customs.18 One of these concerns the way of maintaining the economic terms of scientists’ reproduction as a special layer; in simpler terms, their funding and its sources. From where exactly do all these funds directed towards research come from and how are they distributed? In the case of so-called applied research, funding sources can often be companies; mainly those of a certain size and above that can afford the relevant cost. Whether they collaborate with research institutions or develop on their own, internally, special research and development departments. However, the largest portion of funding, especially when it comes to basic research, comes from state (or federal, see EU) funds – even in countries with corporate giants, such as the U.S.A. The competent state services decide to allocate a specific amount for research within a time frame (e.g. the European H2020); subsequently, various committees and sub-committees, in which scientists may possibly participate (but not only), specify the particular directions towards which this amount will be distributed; and finally, they issue calls – competitions to all interested scientists who meet certain conditions (e.g., nationality). These latter now engage in a race to enter as many competitions as they can, submitting corresponding proposals to the relevant committees, aiming to secure a piece of the pie. Almost as if it were competitions for public works; with scientists being the contractors…

The obvious conclusion from the above: the freedom scientists have to choose the subject of their research is exhausted in selecting the competition that seems to offer them the highest chances of winning. Second, complementary conclusion: the content of research is not determined by any “love for knowledge,” so abstractly and vaguely, nor by any disposition to cover real social needs, but is strategically planned at a central level, based on the current needs of states and (secondarily) companies; that is, based on the harsh needs of capitalist development.19 Scientific research is no longer conducted as a sport of eccentric, noble gentlemen who have the means to devote themselves to their passion, as was the case to some degree 100 years ago. From the end of World War II onwards, when the success of the Manhattan Project for building the atomic bomb became evident, as well as other related military projects run under the close supervision and generous funding of states, research was restructured according to the logic of mass production and targeting increasingly direct and tangible results.20

The list of mechanisms through which scientific “truths” are selected and shaped in specific ways could extend further, but we will not insist.21 The purpose of the previous observations was not to conclude that science produces lies that it serves as truths – something that indeed happens, and more frequently than scientists and ordinary users of technical inventions would like to admit. Nor is it necessary to resort to an extreme cognitive relativism, rejecting any notion of truth. Our intention was more to demonstrate the degree of sociality that exists even in the production of what are considered the most certain knowledges. It is people who are involved in this process, people with particular preferences and life attitudes; and ultimately with specific interests. Which in turn means that every knowledge is produced from a specific positional perspective, and its value is judged based on these interests – even if unrecognized by those scientists who still believe in abstract notions of objectivity. Regardless of what scientists themselves think about themselves, their (socially dictated) role does not consist merely in a careless search for knowledge; they constitute a special layer of intellectuals, serving specific interests (consciously or not, this is irrelevant) and having meanwhile accumulated a huge capital of dead and living labor to produce their “unshakeable” certainties.

Epilogue… with a feeling of nausea in the mind

Can the censorship cases against Trump be interpreted as an attempt to protect public opinion from the fake news spread by a paranoid? Is the hunt for those who criticize the coronavirus management part of an effort to protect public health from irresponsible ignoramuses who deny scientific findings;22 Even when this censorship pandemic has now become a subject of discussion and concern in major mainstream media?23 Obviously not.

The problem with fake news is not that they are produced and disseminated – it is not, after all, something unprecedented. The problem is that the complex of the state and bio-informational companies, in this transitional phase of mutation of propaganda media, has not yet managed to acquire a monopoly on their production. At least in Western societies, given their history and their “entrenchments,” such a thing will take time; however, time that Western elites do not have available in their competition with China and their rush toward the heavens of the 4th industrial revolution. The restructuring of economic and social relations that was already underway for years and accelerated through the health lockdown (but economic lockout) will necessarily require an information intensity strategy: systematic psychological terrorism operations followed by offers of hope and salvation. The disruption of public anxiety must henceforth be punished; initially with simple censorship, with legal prosecutions in the future, if one persists.

They used to say that war is the health of the capitalist machine, since it offers it an opportunity to clear out “obsolete” capital, both dead and alive. The information war unleashed by a nexus of politicians, experts, journalists, and intellectuals (layers that, incidentally, are among the least affected by lockdown policies) has a similar function: to clear out whatever psycho-intellectual reserves of resistance remained in Western societies. It was also the ideal opportunity to test the mettle of various “rebels” and clearly reveal where they stand when the lines are drawn on the ground…

Separatrix

- Australian writer (1922-1987), considered one of the pioneers in analyzing the mechanisms of propaganda in modern urban and liberal “democracies.” Some of his essays have been collected in the volume “Taking the risk out of democracy: corporate propaganda versus freedom and liberty”, 1997, ed. University of Illinois Press. ↩︎

- His most famous related book is “Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media”, co-authored with Edward Herman, first edition 1988. It is worth noting here that in the last decades of the previous century there was intense interest in the Anglo-Saxon world regarding the issue of state and corporate propaganda.

As another example, see “Science of coercion: communication research & psychological warfare, 1945-1960” by Christopher Simpson (Oxford University Press, 1996). In a sense, it is a more simplistic version of studies that had been conducted somewhat earlier (already before the war) in Europe by Gramsci (on intellectuals) and the Frankfurt School (on mass culture); as well as Debord post-war (on the society of the spectacle). These contemporary studies now address an Anglo-Saxon (or anglicized) audience, educated in many “information” and “facts”, without necessarily possessing any particular theoretical depth. Even so, for what it was, it was important. ↩︎ - Example is Bezos, owner of the empire called Amazon, who has also purchased the Washington Post, along with of course the newspaper’s “objective” fact checker, who (allegedly) checks statements by political figures for accuracy. We remind you that the Washington Post (along with the New York Times and the L.A. Times) played a key role in slandering journalist Gary Webb as a conspiracy theorist when he exposed the network set up by the Contras in Nicaragua to push cocaine into the U.S. (which ended up mainly in African-American communities) with the silent complicity, if not cooperation, of the CIA.

Webb’s revelations proved largely accurate over time. He “committed suicide” (with two bullets!) in 2004. The Post is still considered credible… ↩︎ - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Conspiracy_theory ↩︎

- http://theconversation.com/theres-a-conspiracy-theory-that-the-cia-invented-the-term-conspiracy-theory-heres-why-132117 ↩︎

- https://www.nytimes.com/1964/09/28/archives/the-warren-commission-report.html

The term conspiracy also appears in newspaper articles from 1963, but with its legal meaning. See, for example, https://www.nytimes.com/1963/01/17/archives/us-court-rules-cuban-attache-can-be-tried-for-conspiracy.html ↩︎ - deHaven-Smith in his book Conspiracy Theory in America (University of Texas Press, 2013) also provides some additional information regarding the relationship between certain media outlets and the CIA document that support this claim. In our opinion, this cannot be considered proof, which in any case would be rather impossible and would require access to archives that are not yet widely accessible. ↩︎

- Especially with reference to covid. As another example, one can see the dispute between Denis Rancourt and David Kyle Johnson regarding an article by the former (Masks Don’t Work: A review of science relevant to COVID-19 social policy) which supported that the so far studies do not prove the usefulness of masks in preventing covid transmission. The video of their dispute is revealing: https://youtu.be/AQyLFdoeUNk ↩︎

- See the article Dangerous Machinery: “Conspiracy Theorist” as a Transpersonal Strategy of Exclusion, Husting, Orr, 2007, Symbolic Interaction. ↩︎

- Perhaps not coincidentally, since the 19th century onwards philosophical discourse has acquired an unwarranted bitterness (of the sort that Benjamin abhorred), without this always corresponding to real, substantial needs for expressing deeper meanings. Philosophy’s tight embrace with the academic sphere has pushed it to develop an idiolect accessible only to specialists (or to those who possess ample free time); in other words, to cancel itself out, since this kind of “philosophy” nullifies a fundamental element of philosophical discourse: to be the field of exercise for a universal reflection. ↩︎

- The intellectuals, ed. Stochastis, trans. Th. Ch. Papadopoulos. Gramsci would probably also be a conspiracy theorist with what he wrote. ↩︎

- It is understood that there are intellectuals who could in a sense be called “organic intellectuals,” but they do not have the role attributed to them by Gramsci. In the heyday of bourgeois generosity, such cases were more frequent, sometimes even within universities. Nowadays, the phenomenon is increasingly rare. Especially in Greece, none of the important post-war intellectuals produced (nor produces) work within academic walls. ↩︎

- Some information about the “founding fathers” of public relations can be found in the books we have already mentioned, as well as in Trust us, we’re experts!: how industry manipulates science and gambles with your future, Rampton, Stauber, ed. Jeremy P. Tarcher/Putnam, 2001. Also in Scott Noble’s documentary, Psywar: https://vimeo.com/102695015 or https://thoughtmaybe.com/psywar/ ↩︎

- As reproduced in Trust us, we’re experts!: how industry manipulates science and gambles with your future, Rampton, Stauber, ed. Jeremy P. Tarcher/Putnam, 2001. ↩︎

- For more details, see Parliamentarism, power, state, Sarajevo, vol. 78, November 2013. ↩︎

- The book by Rampton and Stauber that we have already mentioned contains several relevant examples of crude directed research. Specifically regarding pharmaceutical companies, one can see the book by Peter Gotzsche, Deadly Medicines and Organised Crime, published by Levantes, translated by S. Euthymiou, edited by S. Euthymiou, Ch. Panotopoulos. ↩︎

- The relevant bibliography is well-known and we will not provide references. For a more specific example, see the book The crisis in physics and the democracy of Weimar, ed. P.E.K., trans. V. Spyropoulou, where it is discussed how quantum theory was influenced at its core of ideas by broader social perceptions in interwar Germany. ↩︎

- Here it should be noted that this entire filtering process, at several of its stages, is not conscious to those participating in it, except of course for the case of crude interventions, where there is not only awareness but also shameless ulterior motives. ↩︎

- A second round of indirect money transfers sometimes occurs from states to companies. If the results of a research program are found to have commercial exploitation potential, it is not unlikely that a company spin-off of the program will be established to undertake the exploitation. Which in turn can be acquired by some larger company. Such an example is the well-known Boston Dynamics of cutting-edge robots, which was acquired by Google. It started from MIT, with money from the state’s DARPA, the research agency of the American Pentagon. ↩︎

- See related the report that Vannevar Bush (engineer, deeply involved in American research projects during the war) had sent in 1945 to the President of the U.S.A., titled Science, the endless frontier. It is considered approximately something like a foundational text of the birth of the new form of science, as it developed after the war. ↩︎

- Even within scientific circles, a sense of melancholy is sometimes expressed regarding the problematic situation that research has fallen into, where it is often impossible to consistently reproduce the findings of many studies (the so-called reproducibility crisis). Ioannidis (now well-known) had already gained a reputation among broad scientific circles (not only medical ones) due to his studies on the issue of false research results and their extensive scope, even before he achieved his current fame. See his article “Why Most Published Research Findings Are False”, PLOS Medicine, 2005. ↩︎

- See UK on high alert for anti-vaccine disinformation from hostile states, Financial Times, Dec. 11, 2020, https://www.ft.com/content/7502f1f1-e104-403d-975f-bedc6e518fe2 ↩︎

- See Coronavirus Has Started a Censorship Pandemic, Foreign Policy, April 1, 2020, https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/04/01/coronavirus-censorship-pandemic-disinformation-fake-news-speech-freedom/ ↩︎