The idea

The idea of integrating European databases with data from EU citizens, as well as those coming to the EU (as tourists or migrants), has been on the discussion table for over 15 years. However, in its early stages, it encountered various issues raised either by the systems themselves, since the development of systems still had a long way to go to meet requirements, or by political freedoms; perhaps more so in terms of privacy and data protection, and less regarding the freedom of movement.

This continued until the attacks in Brussels and Paris in 2015, along with the increased migration flows to Europe in the following years, mainly from the Syrian front. Since 2016, the European Commission has placed the idea of database integration at the forefront, setting specific timelines: estimates suggest the system will be ready by 2023.

Although the technical problem in the application was a matter of time – since the evolution of technology as a science has not been seriously disputed – the issue of political rights had to be resolved somehow. Discussions in committees always had this obstacle, trying to round it off with various institutional measures for proper use and data security. However, because the “proper” implementation of surveillance and control does not leave much room for such – and other – freedoms, and because a capitalism in crisis cannot wait for those with tendencies towards these freedoms to comply, it is more practical not to have too many such discussions; or if they do take place, to base them on the grounds of “emergency.” It is nothing new.

We copy from a relevant report:1

“The events of September 11 had a dramatic impact on the use of biometric systems in the context of migration and security. Until then, biometric systems were being developed as tools for migration management and, like other emerging technologies, were applied on a case-by-case basis through pilot programs. One of their uses was to facilitate frequent travelers by providing a separate “fast” lane for arrivals/departures. Enrollment in the biometric system was voluntary and served as a convenience. As security measures, biometric systems were only used for entry into restricted access areas of the airport (with the exception of EURODAC). Although initiatives to introduce biometric data into passports predated September 11, the events of that day accelerated efforts and established specific timelines for implementation.”2

And from one more:3

“Following the example of the US, the EU’s “security” agenda strongly promotes the use of biometrics […] and has already decided to introduce fingerprints in European passports.

[…]Government responses to the events of September 11, 2001, as well as to other terrorist acts in Bali in 2002 and Madrid in 2004, included decisions for the significant increase in the development and application of biometric and information technologies for recording and verifying identity.

[…]Within the EU, there is increased political interest in expanding identification systems and strengthening border regulations. This is connected to an older and long-standing ambition of the EU: to find ways to ensure the free movement of citizens within member states while managing movement at external borders. Such an ambition is expressed through the EU’s ideal as an area of “freedom, security and justice,” where secure external borders are considered crucial so that the freedoms of EU citizens are not jeopardized by “external threats.” Effective control of individual movement, meaning the regulation of both “internal” and “external” borders, requires the individuation of people in order to determine their rights of access to both areas. The great irony of the EU’s “security” agenda, which gained greater momentum with the Amsterdam Treaty and the subsequent Tampere program of 1999, is that the provision of greater freedom has been closely linked with increased forms of surveillance; surveillance of both non-EU citizens and those within.

[…]The Hague Programme, which succeeded the 1999 Tampere Programme, has recently been issued by the European Commission as the “Hague Programme: Ten Priorities for the Next Five Years.” Many of these ten priorities link the preservation of “freedom” with increased measures to ensure “security” throughout the EU. Priority No. 6 provides the most striking example of the mutual relationship between these two concepts, stating that: “an area where the free movement of persons is fully ensured requires further efforts towards integrated control of access, based on integrated management of external borders, a common visa policy, and with the support of new technologies, including the use of biometric identifiers.”

[…]The history of introducing biometrics into EU passports includes a series of discussions regarding migration and crime; the resolutions on identity and security recording adopted by the Council in 2000 were quickly reassessed after September 11th, and by June 2003 the European Council summit in Thessaloniki confirmed the need to upgrade passport security through the use of biometric technology.”

By April 2019, the project has progressed significantly. Technology has made leaps to meet the requirements; smart algorithms have been trained quite well on data from multiple “sources,” such as through generous samples of voluntary self-promotion on anti-social networks, as well as through the extraction of biometric data from migrants, while network technologies also seem to withstand this large flow of data. It is then that the “green light” is given by the European Parliament for the creation of the mega-database of biometric data.

The implementation

The relevant statement of the migration and internal affairs committee states:4

“Today, the Council approved the Commission’s proposal to address significant security gaps, to unify the EU’s information systems for security, migration and management. […]

Welcoming the approval, Migration, Home Affairs and Citizenship Commissioner Dimitris Avramopoulos stated: «An effective Security Union must ensure that national authorities and EU agencies can cooperate seamlessly, connecting the dots between information systems for migration, borders and security. Today, we are creating a crucial pillar of this project, providing border guards and police with the appropriate tools to protect European citizens».

Today’s approval marks the final step in the legislative process. The text of the regulation will now be published in the Official Journal of the European Union and will enter into force 20 days later. eu-LISA, the EU agency responsible for the operational management of large-scale information systems in the area of freedom, security and justice, will then begin the technical work of implementing the interoperability measures. This work is expected to be completed by 2023. The Commission is also ready to assist Member States in implementing the regulation.”

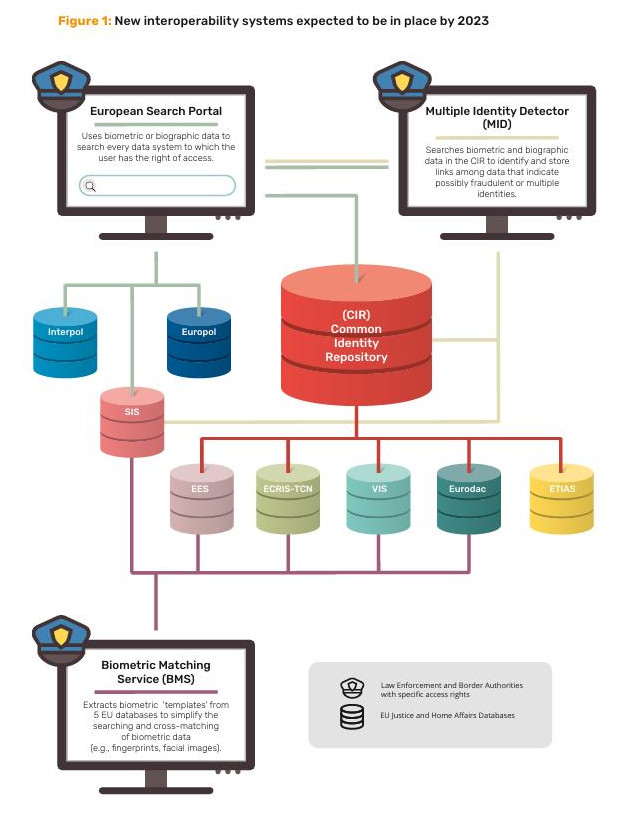

The mega-database is called CIR (Common Identity Repository) and its implementation was approved by the European Parliament on April 15, 2019. The goal is to unify all existing databases in the EU5, containing data on over 350 million people, including identity records (name, date of birth, passport numbers, etc.) and biometric data (initially fingerprints and facial photographs), and it will be the third largest biometric database, after those of China and India.

In October 2019, eu-LISA organized a conference in the Estonian city of Tallinn, where EU officials and representatives of the technology sector discussed ways to put “interoperability” into practice. Speakers from software companies specializing in artificial intelligence and biometrics gave presentations, as did a representative of US “border security” (US customs and border control), who explained that part of the core technology now used for border control was developed immediately after September 11 to combat terrorism.

“The data in the CIR database will be collected from five other databases. Two of these – which contain fingerprints of asylum seekers and data related to short-stay visa applications – are already operational.

Two others include a system replacing passport stamps by recording all movements of third-country citizens, in and out of the EU, and a program requiring visitors who do not need a visa to submit an entry application to the EU.

The final piece of the puzzle – a file collection system designed to help national authorities know whether foreigners have previous criminal convictions in the EU – will also maintain data on EU citizens with dual nationality.

The proposed legislation comes at a considerable cost: Brussels has allocated 425 million euros for the period 2019 to 2027 for implementing the ‘interoperability’, with each country expected to cover part of its own expenses. Germany estimates it will need to spend up to 92 million euros. Creating the new border control and travel authorization systems under the plan will cost the EU another 690 million euros.”6

In June 2020, the eu-LISA agency signed contracts with at least two companies, IDEMIA and Sopra Steria, to implement a biometric database of approximately 400 million “third-country nationals” by 2022. Whether this biometric data will remain limited to fingerprints and facial images, we cannot yet know.

“In February (2020), leaked documents showed that police forces in the European Union plan to create an interconnected network of facial recognition databases across the EU.

A report from the EU Council, according to sources, was circulated among 10 member states last November, with detailed measures proposed by Austria, for legislation to create a network of facial recognition databases that could be used by police forces across the bloc.

The documents published in ‘The Intercept’ correspond to a series of reports examining whether the Prüm Treaty, which contains rules for operational police cooperation between EU member states, should be extended to include facial images.”7

However, the “idea” (in the sense of the tendency that the bioinformatics-security complex appears to have) is rather to push the issue even further:8

“The practical application and utility of biometrics in personalizing bodies, to facilitate their identification, is consistent with current uses of DNA identification, a technology that is used to collect and represent the uniqueness of individual bodies at a molecular level. […] It currently provides the most systematic and rigorous way of personalizing people and is widely recognized as a proven method for the reliable and repeated recognition of individuals and their bodily traces. For these reasons, DNA identification and its collection in databases are often referred to as invaluable resources that could potentially be developed as technologies capable of providing security in the EU. A particularly prominent instance of this claim was made by David Blunkett at the G5 summit conference held in Sheffield in July 2004, when he emphasized that biometric technologies can essentially contribute to national and public security, not only by facilitating identification at national borders but also by aiding in ‘intelligence-led policing and closed-border cooperation.'”

The point of no return

The criticism so far comes from academics, based on questioning the validity of biometric identifications, due to the increased likelihood of “false positive” results, as well as from privacy advocacy groups:

“The French digital rights advocacy group La Quadrature du Net filed a legal complaint with the country’s highest administrative court in August, against the use of facial recognition by the police.

The French police have a database of approximately 19 million files, including 8 million individuals.

The group states that police in France use facial recognition “systematically” in public spaces, “for many years” without justification or legal framework. Despite calls for public dialogue from the French government, the group states that facial recognition has already been established in the country, from “exercises” in Nice and the “Parafe” entry gates at border crossings and airports, as well as with the Alicem digital identity program.

The Traitement des antécédents judiciaires (TAJ or processing of criminal records) will include images of people who have not been found guilty of a crime, says La Quadrature du Net, and even more people will be “trapped” in France’s biometric system.

The group argues that the system “makes everyone a suspect” and allows authorities to identify and track people by their faces.”9

Accordingly, the European Data Protection Supervisor (EDPS) criticizes the creation of such a mega-database:10

“Interoperability is not a technical decision; it is primarily a political decision. In the context of integrating distinct European laws and policy objectives (e.g., for border controls, asylum and migration, police and judicial cooperation in criminal matters), as well as by providing law enforcement authorities access to databases not related to law enforcement, the EU’s decision to create large-scale interoperable systems will not only permanently and deeply affect their structure and mode of operation, but will also change the way legal principles are interpreted, marking a ‘point of no return’.

[…]

The EDPS is concerned that the repeated reference to migration, internal security and the fight against terrorism, (stm: as pretexts for creating the mega-database) risks blurring the boundaries between migration management and crime and terrorism fighting. It could even contribute to equating terrorists, criminals and migrants […] and considers that the objectives of combating illegal migration are overly broad and do not meet the requirements of “strictly limited” and “precisely defined” use of such a system, as required by the Court’s proposals.”

Such objections were appearing in the “European dialogue” until recently, and probably slowed down somewhat the pace at which the authorities would like their “ideas” to be implemented. So, it seems they seized the “opportunity”: “Aaah… isn’t controlling migration as an excuse enough for you? Take a health-related terrorism now, let’s see what you’ll answer.”

And if anyone has doubts about what daily life would be like in a European bio-fortress, they can take a look at the reality of migrants; where the real “point of no return” lies.

Wintermute

- Biometrics and international migration – Jillyanne Redpath, Ann Ist Super Sanita 2007 Vol-43 ↩︎

- EURODAC is a European fingerprint database, created in 2000 with the purpose of recording and checking asylum seekers. ↩︎

- European securitization and biometric identification: the uses of genetic profiling – Paul Johnson and Robin Williams, Ann Ist Super Sanita 2007 Vol-43 ↩︎

- Security Union: The EU closes gaps between information systems for security, borders and migration management – 14 May, 2019 ↩︎

- More information in the related images. ↩︎

- EU pushes to link tracking databases – Politico, April 15, 2019 ↩︎

- EU signs contract for large-scale biometric database to protect borders – Euractiv, June 4, 2020 ↩︎

- European securitization and biometric identification: the uses of genetic profiling – Paul Johnson and Robin Williams, Ann Ist Super Sanita 2007 Vol-43 ↩︎

- EU police face biometrics system debated by lawmakers, experts concerned about false positives – Biometric Update, September 23, 2020 ↩︎

- Interoperability morphs into the creation of a Big Brother centralised EU state database including all existing and future Justice and Home Affairs databases – May 2018 ↩︎