Great vision over the streets, like autumn leaves

the cries were scattered.

The city had been lost beneath the lights, the flags, the

shouting. We were celebrating the victory.But at the same time someone gets up in the silent

T. Leivaditis, A Small Book for Great Dreams

house, doesn’t turn on the light, gets dressed and sits in the

darkness.

No one can help him.

What common ground could VAR1 in football possibly share with coronavirus management? The question is not provocative (not very much, at any rate). At first glance, the answer seems trivial. Either there is no common ground at all, or there are so many connections that the question ultimately becomes meaningless. We argue that there is a significant common ground, and that the threads linking these two seemingly unrelated aspects of society may be difficult to discern, yet they are real and indeed quite resilient. There is a specific web of meanings and practices that allows for a transition from VAR to the coronavirus and back again. Let us rephrase the question in a slightly different way. On one side we have one pole, one point of convergence of these threads: the institution of football (or any other sport) with its various practices of shaping and describing bodies and behaviors—first and foremost those of athletes, but not only. On the other side, an unprecedented biopolitical campaign for population management, which, having first turned homes into prisons with designated hours for outdoor activity, now aspires to capture cells themselves, subjecting them directly to the logic of capital. Does the question, framed thus, perhaps reveal that there might indeed be common ground underlying the logic of (professional) sports and that of medicine?

The dominant perception regarding the function and origin of sports sees it as a human constant, with its birth lost somewhere in the depths of the ages. Almost every minimally organized society has activities that could be called athletic, from the Olympic Games of ancient Greece to the rubber ball games of Mesoamerican civilizations. From this perspective, therefore, sports resemble a pan-human need that transcends cultures, eras, and places—something like the Paparrigopoulos myth of the famous uninterrupted continuity of Hellenism through the centuries. Such an observation, however, true as it may be, is extremely shortsighted when formulated in such a broad, macro-cultural generality. The modern Olympic Games are not a simple revival of their ancient Greek counterparts, even though they relied precisely on such a mythology for their legitimization. And it would be an unforgivable historical sleight of hand to attempt to equate modern football with Mesoamerican ball games. To understand the logic and function of modern sports, one needs the magnifying glass of historical criticism, which can provide a more specific and focused examination of how these sports are embedded within the broader perceptions, institutions, and ideologies of capitalist hyper-mature societies of the 21st century.

Sports – ceremonies

The Olympic Games, in particular, are a good example of how the meaning of a practice can change radically from era to era, even when it remains almost unchanged in its external characteristics—the track and field events (most of which are extremely simplistic in their conception anyway) remain more or less the same. A first notable difference between the ancient and modern games concerns the social position of participants within the general division of labor.2 Ancient “athletes” were not athletes in the modern sense of the term. They did not pursue a sport professionally, did not make a living from athletics, and were not professional entertainers. They were free citizens (and certainly not the property of any sponsor or agent), typically of higher social status and origin, enabling them to dedicate time to training, yet their identity was not fully defined by this activity. Athletic practice was organically integrated into what could be called the cultivation of virtue; however, it must be understood here that the term “virtue” referred not to moral but to political and social qualities—morality, in its modern, individualized sense, was underdeveloped in the ancient world until the emergence of Stoicism. People trained in their role as citizens, and among their duties was the readiness for war, both in character and bodily form. For this reason, a serious deformity or disability could constitute a significant obstacle to attaining higher offices.

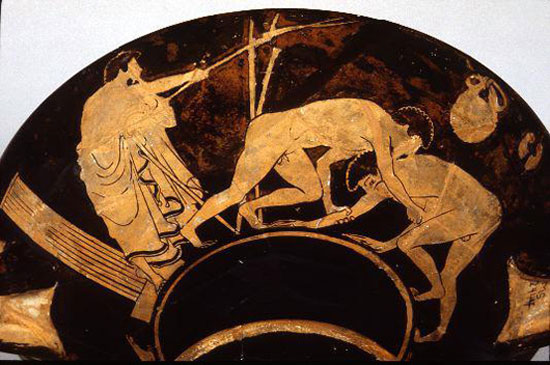

Equally significant, and perhaps even more striking, is the fact that the level of violence tolerated in ancient games was considerably higher than what we would consider acceptable today. Wrestling matches in the well-known pankration had almost no rules and certainly far fewer than even today’s MMA competitions. Defensive retreat, although not explicitly forbidden by any rule, carried the stigma of dishonor for the athlete who lacked the courage to withstand the blows of their opponent. It was therefore not uncommon for these contests to end not only in serious injuries but even in death, sometimes in horrifyingly gruesome ways (the story is known of an athlete who used his fingernails to rip open his opponent’s abdomen and extract his entrails).3

Ancient sports and athletic competitions thus carried a seriousness unusual by today’s standards. It is indicative that we cannot classify ancient athletes according to our own categories: by definition, they were not professionals, yet they were certainly not amateurs either. They resembled participants in a particular kind of ritual, a notion that becomes even more evident when we consider that the Olympic Games were held in honor of Zeus and accompanied by numerous religious ceremonies. In no case did they function as an opportunity for free entertainment, accumulation of fat, or wasteful expenditure of leisure time. The close connection between athletic contests, religious rituals, and mythology was not a unique characteristic of the ancient Greek world. Similar perceptions and practices are found in cultures vastly distant (both geographically and temporally) from ancient Greece, such as those of North and Central America, where the religious element could be even more intense and concern for the outcome (who wins) nearly absent (in pankration, even the dead could be crowned as victors).4 These examples do not necessarily mean that every athletic activity is rooted in religious rituals; however, they are sufficient to demonstrate that the logic of sport and competition can differ so radically between two different societies that it becomes difficult even to translate the athletic terminology of one into that of the other.

The birth of modern sports

As for modern sports now (at least those originating from Europe, usually from Britain), if we “must” historically identify a specific point in time when they were born with their current more or less meaning, then this point is mainly located in the 19th century and more specifically in its second half.5 During the Middle Ages, various versions of team sports that later became popular were quite widespread, such as hurling (resembling an ancestor of rugby), as well as numerous others referred to as football/handball, although there is insufficient information about exactly how they were played. In any case, these were characterized by much higher levels of aggressiveness and violence (death was again a possibility) compared to their “descendants” and followed a different logic. The competitions usually took place within the framework of (religious) festivals, had far fewer rules (though not completely anarchic), and the definition of a winner was something quite vague and not necessarily of particular importance.

Attempts to suppress these savage forms of “entertainment” among rural populations through royal decrees had occurred frequently throughout the late medieval and early modern periods. Overall, they were resoundingly unsuccessful. Such suppression only became feasible from the 18th/19th century onward, coinciding chronologically—but not coincidentally—with the rise of advanced industrial societies and the absolute dominance of the urban class. As rural populations were violently proletarianized and driven into new urban environments where they were crammed into microscopic apartments to work exhausting hours, they no longer had the space, time, or physical and mental reserves to indulge in such “pleasures.” Moreover, these “pleasures” did not receive the approval of the conservative urban strata and their puritanical work ethic. The “paradox” here (or dialectically interesting, if you prefer) is that it was this same urban class—who had previously banned these activities for the working population—that revived these sports. Initially, they began somewhat hesitantly as activities for students in the schools attended by the children of the upper classes, so that these young people could channel their energies—including sexual energy—in some way (as the ever-wise and all-knowing teachers of the time, as well as today, believed). However, these sports quickly gained popularity among broader circles, to such an extent that by the end of the 19th century, the first disputes erupted regarding the status of athletes and whether or not they should be allowed to receive payment—up until that point, the morality of the upper classes considered it self-evident that athletes should be strictly amateurs and not “workers” of sport.

In any case, the important thing here is that whatever sports eventually gained popularity did not revive in their original form, but with a completely different and rather disjointed logic. First, the acceptable level of violence dropped sharply. Deaths and serious injuries became unthinkable; hence, the much more detailed and sensitive definition of fouls and permissible moves. According to analyses by Norbert Elias and Eric Dunning, this can be interpreted based on the assumption that sports, like Western societies as a whole, underwent a process of “civilization,” with the state acquiring a de facto (not just de jure) effective monopoly on violence, and the upper classes finally finding a balance point in their mutual hostilities. Even the emergence of parliamentarianism at that time expresses precisely this process of pacification in the upper echelons of the social hierarchy, according to which the alternate but peaceful assumption of power by different factions is accepted by all “players,” so that there is no longer the fear that the loser will end up facing the guillotine.6 Rhetorical battles in parliament proved ultimately preferable to real brawls with actual dead. In this way, overall acceptable levels of violence (unless originating from authorized state bodies) decreased across all expressions of developed Western societies, including sports. Sports began offering a mimetic revival of emotions stirred in real battles, but with almost negligible risks.

However, it was not only the tendency to reduce levels of violence that led to the introduction of more and more rules and prohibitions. The logic of measurement and quantification, already dominant in the broader social imaginary, began to infiltrate sports as well, especially once professionalization advanced at a rapid pace, resulting in an ever-greater emphasis on the outcome of the game and on the winner.7 A characteristic feature of this (quasi-Weberian) tendency toward bureaucratization is the obsessive preoccupation with records. As Huizinga informs us, the word record (from Latin recordari = to remember) originally simply meant a mnemonic device, a notation made by an innkeeper to remember his customers, and eventually came to refer generally to the extent of trade.8 From there, it was transferred to modern sports, gaining increasingly central significance as the process of quantification deepened to such a degree that it acquired fetish-like status. The deployment of statistics for comparative purposes, both in economics and in sports, however, imposes a specific set of values. More specifically, it brings about a re-evaluation of the very concept of time. In pre-modern times, a contest, embedded within a ritual framework, often had a high symbolic value, expressed as a reenactment in the here and now of a past, mythological moment. Through the cyclical revival of the past within the present, it acquired a “conservative” function for society, renewing its self-understanding, but with its gaze turned toward the past.9 In modern sports, the “mythology” of statistics fulfills an essentially different role. The linear time on which comparable quantities are arranged acquires a clear directional progress. The past becomes useful to the extent that it can be compared with the present, and the present must be surpassed by the future through new records. The now is always better than the before, but never as good as the after. Citius, altius, fortius.10 Even the salvific eschatology of Christian theodicy was ultimately bureaucratized, hidden behind numbers and records.

Another consequence of professionalization was a dual split within sports: on one hand, the divide between professionals and amateurs, and on the other, that between players and spectators. But what could be the consequences of such a “paradigm shift,” which proceeded through a dual fragmentation of the original unity of play? The distinction between professionals and amateurs implies a (not-so-)hidden evaluation regarding the seriousness of engagement. To maintain the right to attribute seriousness to an activity, that activity must be mediated by the logic of anticipating an exchange. Outside such a logic, any engagement is automatically, almost reflexively, categorized as harmless entertainment. Ultimately, it is normalized as what has become conventionally known as a hobby, almost always bearing the stigma of an unconscious guilt. At best, the “hobbyist” gives the impression (sometimes even cultivating it themselves) of a charming eccentricity. At worst, when passion and obsession take hold, they relish their marginalization into the oblivion of peripheral visibility.

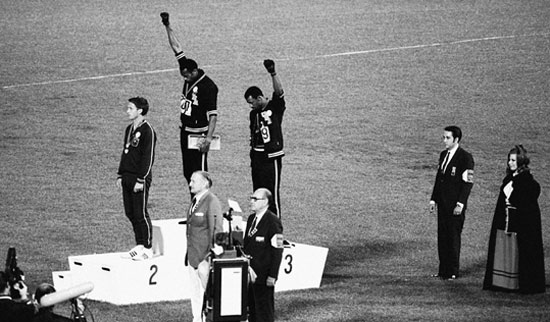

The second distinction, that between athletes and spectators, was of course nothing new. In combination with the first, however, the gap between the two levels of participation becomes endemic, if not structural. And this indeed was new. In an activity you participate seriously either as an athlete, a privilege that only a few are destined to enjoy, or as a spectator, as part of a crowd whose role is exhausted somewhere between applause and the construction of an elaborate repertoire of abuse ready for use against the “others,” the “ours,” and the “crows.” Beyond whatever cathartic functions the role of spectator may indeed perform, here we are interested also in its significance as a model and structure of action. Even the most extreme behaviors are permitted and forgiven, even encouraged, as long as they remain at the rhetorical level. Action is allowed only as rhetorical participation, that is, as non-action.11 Discourse acquires weight only to the extent that it remains empty of practical reference. Yet this was precisely the model of “action” and existence for the citizen of mass, democratic societies of the early twentieth century.

Sports as a Constructed Spectacle

The above applies naturally to sports spectacles of the 21st century. These are developments whose consequences still spill into today. However, additional layers of capitalist distortion have settled upon them over recent decades—starting already from the post-war period—turning professional sports into a pure form of Spectacle (for those who have eyes to see and not invested interests, such as the bias of sports journalists) and even influencing those who participate in sports amateurishly or even those who don’t participate at all.

We did not use the term Spectacle randomly or exaggeratedly. If until the Second World War sports had been “refined,” quantified, and bureaucratized to a large extent, they nevertheless remained, despite all this, what we might call a “superstructure” of capitalist accumulation.12 It was neither outside nor opposed to the capitalist, Fordist logic of mass democracies, yet it was not at their core either. The sphere of hard production still had priority. However, as the circles of capitalist accumulation expanded to encompass ever-larger areas of the social, sports followed the fate of so many other, until then relatively autonomous, fields (such as art), to end up beneath the caterpillars of the capitalist machine.

Since every capitalist formation, by its very nature, must constantly struggle against impending crises of overproduction, a sure way of protection is always the advance into new fields of exploitation. In its most mature phase (what Ernest Mandel called late capitalism), capitalism tends toward a universal subsumption of society under capital. It is not only the hard production of tangible goods that must be organized industrially, but also the “superstructure”: culture, art, leisure time, entertainment, sports, even daily experience itself. Whatever belongs to what we would call the “symbolic order” is now organically incorporated into the logic of commodity circulation, and not merely as a side effect or appendage. For the social factory to function smoothly, it must continuously construct and produce symbols, meanings, identities, or even experiences—all available for consumption and without necessarily any coherence.13 The following excerpt is from Trotski.14 We have cited it before on another occasion, but we bring it back here because it is particularly telling:

“When capital conquers all spaces that lie outside capitalist production proper, it initiates a process of internal colonization; indeed, only when the cycle of civil society—production, distribution, exchange, consumption—is completed can one begin to speak of capitalist development proper… At the highest level of capitalist development, the social relation becomes a moment of the relation of production, the whole of society becomes an articulation of production; in other words, the whole of society exists as a function of the factory, and the factory extends its exclusive sovereignty over the whole of society.”

Professional sports experienced great glory in the postwar period precisely because it managed to successfully integrate itself into the factory production of symbols and experiences. It was a relatively cheap product to produce that could easily be transmitted to millions of spectators. From this perspective, it was also an ideal way to colonize leisure time, which had been so hard-won in the prewar period. But it was also a way to offer “thrilling” experiences, at the same time that slogans against workplace boredom and daily routine were being heard in the streets. It was not, of course, the only such way; the film and music industries, for example, were already considerably more mature, although with the “disadvantage” that consumption of their products was passive, especially in the case of cinema. In any case, however, sports also became an inseparable part of the Spectacle, a machine for producing virtual moments and yet another channel for spreading the psycho-intellectual panacea.

Beyond (but also complementary to) its economic value as a link in the commercial circuit, equally important for professional sports is the fact that it also functions additionally as a factory for producing identities. The more societies become bureaucratized and algorithmic, the more the value that each self can attribute to itself actually decreases, realizing that it constitutes nothing more than a link in a long chain. Something that is, of course, not sustainable in the long-term for any society, let alone for 21st-century Western societies that have been imbued with the ideologies of individualization and the importance of the self (although they may soon learn that it would be best to forget such delusions). They must provide their subordinates with a sense of meaning and identity. In various ways, among which is the construction of fan identities. The interest here – and so fitting for postmodern societies – is that fan identities are now completely devoid of content, they have no signified to which they can root – even the spatial affinity of the fan with the team’s headquarters (because there is no longer any question of affinity with the players) plays an increasingly smaller role. From this perspective, fan identities resemble an archetypal application of the famous principle of the arbitrariness of the sign in linguistics. It does not matter so much what they refer to, but rather that their oppositions, like those between linguistic signs, can set in motion mechanisms for producing meanings.15

What is characteristic of sports, however, is not that it is “simply” another field where consumerist mania is exercised. It concerns the bodies themselves and how they become intelligible; initially those of the athletes, but subsequently also of anyone who wants to be considered healthy. Many are those who today frequent gyms in order to stay in shape, sweating over benches and grunting under weights. But how many of them know why they exercise in this way? Is there (or has there been) any other way? The answer is clearly affirmative.16 Until the beginning of the 20th century (even up to the war), an athlete’s training had nothing to do with strengthening or enhancing their performance, as it is understood today. The purpose of training was supposedly to highlight the athlete’s inherent (i.e., genetically predetermined) potential—we must not forget that it was the golden age of eugenics. This would be achieved by following the popular principles of energy conservation at the time: the athlete’s movements (e.g., arm position in speed competitions) had to be adjusted in such a way as to acquire a grace that would prevent them from wasting energy—it was, of course, a logic inspired by Taylor’s analyses of workers’ movements. Training manuals, however, were quite lacking in the part concerning the athlete’s physical exercise; they contained few training tips along with some additional advice on avoiding alcohol and tobacco abuse. The athlete’s training consisted of repeating what they would do in the competition; if you were a sprinter, you simply had to run during your training sessions and not spend hours on specific strength-building methods.

A real paradigm shift in athletes’ training would occur after the war, when professional sports took off and the emphasis on performance took the form of a mania. It was then that a new form of training spread widely: one that uses resistance, short periods of intense exercise interrupted by breaks, progressive increase in difficulty, and focus on specific muscle groups. In other words, exactly what any gym regular does today. Some early indications that such a type of training increases performance already existed before the war. However, it wasn’t only doctors and physiologists who were interested in such research. One of the laboratories that conducted cutting-edge research in the field of bodily performance was the so-called Harvard Fatigue Lab (which closed shortly after the war), under the auspices of the Harvard School of Business. However, the laboratory’s purpose was not to improve athletes’ performance, but to provide knowledge and guidance to managers regarding “human resource management.” Therefore, among the pioneers behind these new training methods were also descendants of Taylor. Every time a dumbbell is lifted in today’s gyms, somewhere deep down, a Taylor smiles.

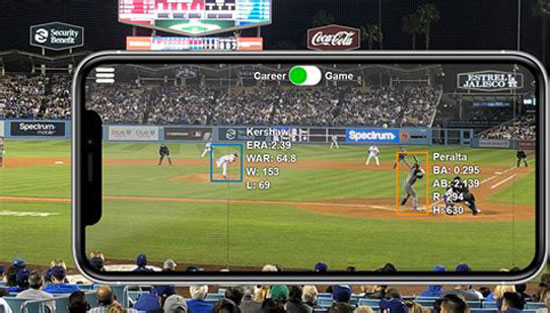

What would have been difficult for Taylor to perhaps imagine was that performance could ultimately be improved through other means as well. It is of course not paradoxical at all that the entire history of athlete doping began immediately after the war and naturally continues uninterrupted to this day, despite the efforts(?) of states and sports organizations to limit the phenomenon – although it is not certain at all that they would actually want to do so. Doping, however, is simply the most obvious case of artificial enhancement. The consumption of proteins or creatine is not typically considered doping. Nevertheless, it would be extremely difficult for an athlete to consume such quantities of proteins exclusively through diet. And if we take one step further, correcting vision problems in professional basketball players to improve their shooting accuracy (as is already happening) should be considered some form of enhancement; and at what point should an athlete’s “work” for self-enhancement finally stop, when apps are already circulating that monitor them even during their sleep to see if they are resting enough or even make recommendations on when to turn off their electronic devices at night?17 Such questions may in any case remain forever pending. The trend – but also the already existing reality – is specific, however. Modern athletes are now produced as products through a long chain of interventions, first on their bodies, but even on their behavior and their “image.”18 It thus appears that professional sports have now become a testing ground for new technologies related to body monitoring and quantification. From this perspective, it does not differ much from the role of the military in developing new technologies: there, new wonders of science and technology are first developed before being served to the general public for mass consumption.

The worn-out phrase that “athletes must be role models” can therefore be essentially accepted even by those who would otherwise reject its more superficial meaning. The acceptance of the logic that the body can become an endless field of interventions, the acceptance of the perception that not only can bodies and behaviors be monitored, but that they must be, lies exactly at the core of the logic of 21st-century hyper-late capitalism. They constitute part of its strategy in its attempt to infiltrate bodies as it extends its mycelium even into the cells themselves. Yet let none of them worry. They will still be able to enjoy whatever spectacles they wish in front of their television and computer screens. In any case, such spectacles never truly belonged to them. Now, simply, their own bodies won’t belong to them either.

Separatrix