First Snapshot:

Programmed bio-computers. None of us can escape our own nature, our nature as programmable entities. Each one of us can literally be nothing more than our programs; nothing less, nothing more.

Despite the vast variety of available programs, most of us possess only a limited set of programs. Some of these are hardwired within us. In simpler life forms, the programming is encoded in the genetic code, eventually leading to fully developed organisms that reproduce upon reaching adulthood. Behavioral patterns, patterns of action and reaction, were determined by the necessities of survival, adaptation to slow environmental changes, and the transmission of the code to offspring.

Eventually, at some point, the cerebral cortex emerged as a new, expanding, higher-level computer with the ability to control the structurally lower levels of the nervous system, the lower-level program recordings. For the first time, learning behaviors and a faster adaptation to a rapidly changing environment began to appear. Moreover, as this new cortex expanded over the course of millions of years, it reached a critical size. At this level of organization, a new capability emerged: the ability to learn how to learn.

Second snapshot:

“If I gave you a third eye, and that eye could see ultraviolet radiation, then that would be a function that would be integrated into whatever you do. If I gave you a third ear with the ability to hear very high frequencies, like a bat or a snake, then you would integrate all these senses into your empirical experiences and use them to your advantage. If you can see at night, then you are better than someone who cannot.

Let’s say I gave you a third hand and then a fourth. You would become more capable, you could do more things, right? And if you could control four hands with the same ease that you handle two hands, then you could do double the work compared to your usual level. It’s that simple. You increase your productivity so that you can do whatever you want to do.”

Third snapshot:

“We focus on a specific type of learning: the acquisition of cognitive abilities. The hypothesis from which we start is that, at certain optimal moments during the educational process, precise stimulation of peripheral nerves can enhance the release of various chemical substances in the brain, such as acetylcholine, dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine, which in turn promote and strengthen neural connections in the brain. These are the so-called neuromodulators that contribute to regulating synaptic plasticity, the process through which connections between neurons change during education to improve brain function. By combining peripheral neurostimulation with conventional training practices, we aim to harness endogenous neural circuits to improve the learning process, facilitating the cooperation and coordination of neural networks responsible for cognitive functions.”

All of the above excerpts could easily originate from some dystopian work of science fiction. In the first one, one might imagine the character of the philosopher-visionary with his calm, deep voice delivering some lecture as an introduction to the basic thematic motifs of the work. In the second, a video plays on the aerial advertising giant-screens of the city, proclaiming the propaganda of the hardworking corporate giant-colossus that functions as a second government within the world of the work. In the third, a scientist on the company’s payroll, wearing a white blouse and with a disheveled appearance, tries to explain to his superiors in as simple terms as possible (but also sufficiently dry so as to gain a few confidence points) exactly how the latest product line being prepared by his team works.

However, no. Everything is snapshots of a real historical process that has been unfolding with impressive consistency (for those who have the necessary clarity of vision and do not suffice to regurgitate endless, but very convenient, “revolutionary” commonplaces) for at least the last seventy years. In 1968, while the streets of Western metropolises were filling with slogans, fires, and tear gas, John Lilly, a neuroscientist, psychoanalyst, and one of the godfathers of the psychedelic faction of the 1960s counterculture1, published his book “Programming and Metaprogramming in the Human Biocomputer.” The first excerpt comes from this book.

The second belongs to Geoff Ling2, a military doctor who founded and directed the Biological Technologies Office of DARPA, the research department of the U.S. Army, from 2014 to 2016.

The third can be found on DARPA’s official website. It describes one of the funding programs that the agency has initiated toward the direction of neuro-engineering, the Targeted Neuroplasticity Training program (launched in 2016)3.

DARPA likes to present itself as the agency that defies contracts and dares to fund “crazy” high-risk projects, which, if successful, could yield great benefits. This perception of DARPA is, of course, part of the mythology surrounding it and simply another, clever way of saying that its research focuses on cutting-edge areas, touching (or possibly even surpassing) existing ethical or legal boundaries (aided by the permanent “state of exception” under which the military operates). Its programs may exude a sense of hyper-ambition (bordering on science fiction), but they are quite firmly grounded in the reality of scientific research, closely following its pace. In other words, those who rush to dismiss such ideas as the delusions of a former superpower in decline may suddenly wake up from the slumber of justice they still enjoy. The techno-scientific complex is charging toward the conquest of the “spirit,” already carrying in its quiver some initial, seemingly impressive results.

In 2015, one could read the following summary from an article published in the high-impact journal Neuron4:

“The idea that memory is stored in the brain in the form of physical changes dates back at least to Plato, but it wasn’t until the 20th century that it was further developed, when two significant theories emerged: Richard Simon’s ‘engram theory’ and Donald Hebb’s theory of ‘synaptic plasticity.’ Although many studies have been conducted since then, each confirming some aspect of these theories, until recently there was a lack of definitive evidence for such engram cells and circuits. In recent years, the combination of transgenic, optogenetic, and other technologies has enabled neuroscientists to begin the process of identifying cells that carry mnemonic engrams, by locating specific groups of cells that are activated during the learning phase, as well as through mechanical manipulation of them, making it possible not only to recall a memory, but also to alter it.”

The perception that human memory can be equated with a warehouse where one organizes things into boxes to retrieve them later or even discard them (as if they were garbage and recyclable paper) is of course not at all self-evident, and for this reason it is not (socially) innocent. Most likely, the fortunate authors of the aforementioned article inherit such a perception ready-made, being themselves an organic part of the dominant epistemological paradigm within which they work. The sophisticated theoretical distinctions and historical investigations – genealogies at minimum, as a duty and a sign of intellectual integrity towards such a weighty concept as “memory” – obviously do not fall within their job responsibilities (they might even be counterproductive when one wants to boost their publications).

It is not, of course, only because of intellectual backwardness that such perceptions can be expressed with the greatest naturalness from the lips of specialists. They are also convenient from another point of view. Their simplicity can sometimes provoke mocking reactions, but it has an important advantage: it allows memory to lie down on the neuroscientist’s anatomical table and be examined experimentally, as a mechanism of boxes and switches, free from historical baggage and social loads. When, however, memory is dried out from the juices of historical and social life, it would perhaps not be unfair to speak of an autopsy over a mummy; necrophilia and necrophilism are, after all, not uncommon vices among specialists. Just as, however, a corpse still maintains a relationship with the living organism, so too in memory-as-storage some similarities with living memory still survive. And when someone is determined to experimentally locate such similarities and has the necessary funding, it finally becomes very likely that they will find them and present them as sensational scientific discoveries – thus preparing the ground for the gradual conformity of living memory as a whole with the model of memory-as-storage.

2011 may be historically recorded as the year of birth of selective memory deletion technologies. A group of researchers reported successful experiments in deleting painful memories in mice via the injection of a substance into their spinal column5. These painful “memories” in the case of the mice referred to the hyper-sensitivity they had developed in their paws following repeated applications of capsaicin (the same substance contained in peppers and responsible for the burning sensation they cause). This particular discovery was welcomed as highly promising for treating chronic pain6.

Two years later, another research team published the results of their investigations on the transfer of memories from one organism to another7. The unfortunate mice once again played the role of experimental subjects. A group of mice were called upon to perform a learning test while at the same time the neural activity patterns of their hippocampus (a brain structure considered crucial for “encoding memories”) were recorded via electrodes. When similar electrodes were placed in mice that had never before performed this test and the researchers “hit replay” to “transfer” the recorded neural activity to the hippocampus of the newly recruited mice, these demonstrated faster learning rates. As if a fast-track training program had been pre-loaded into their brains.

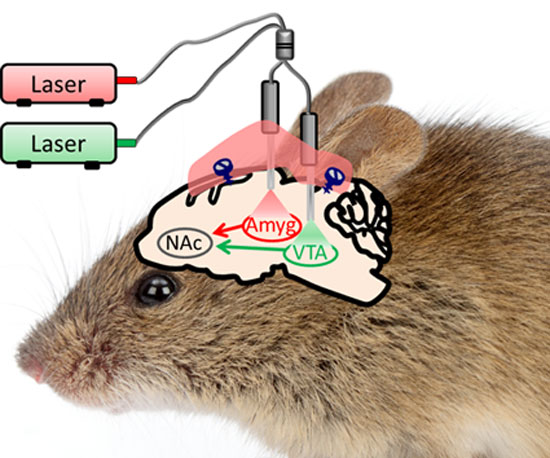

As expected, the techniques of memory transfer did not remain stagnant. 2019 was the year when the possibility of creating memories de novo was announced, no longer requiring the training of mice that acted as “memory donors”8. It suffices to record the neurons activated during exposure to stimuli A (a specific odor) and B (an electric shock) and then simultaneously activate them in the recipient mice so that they learn that A is associated with the painful B, exhibiting avoidance behaviors toward A. This means that, without ever having been previously exposed to stimuli A and B, they have learned to associate them – normally, without training, stimulus A (the odor) should be neutral to them and not provoke a negative reaction.

It seems, in a rather paradoxical and broken way, to confirm Lilly’s hypothesis about organisms as programmed and programmable bio-computers. On the other hand, it is certainly extremely doubtful whether Lilly had in mind deletions and implants of memories. For him and his companions then, the issue was the possibility of endogenous change of behaviors and not their exogenous imposition. However, their failure lies in the fact that, in an attempt to scientifically legitimize their pursuits, they rode the wave of the mechanization of the spirit that had already begun to swell from the 40s and 50s at least. Computers were already presented during the war as giant super-brains, while techno-scientists had placed at their center the hypothesis that brain and nervous system operate on principles similar to those of computers (see the well-known Macy conferences on cybernetics and systems theory, which are considered something like a birthplace of cognitive sciences).

No matter how impressive such experiments may appear, they nevertheless leave behind some fundamentally vexing questions. What is the relation of these laboratory experiments to reality? What do they ultimately tell us about the memory of living organisms? Do they function as simple mirrors, providing unambiguously interpretable results?9 No experimental condition, of course, aspires to represent within the laboratory walls the aspect of reality under study in its entirety. A certain simplification is always presupposed, a forced omission of those elements of reality deemed to be of lesser significance for the phenomenon under investigation—just as a map obviously does not need to recreate a city in its entirety, which would in any case be useless and contrary to the very purpose of mapping. The experimental condition is always also a (perhaps early) modeling, an attribution of meanings and a hierarchization of the elements of reality; for this reason, it cannot therefore ever be simply “experimental” and rawly “empirical.” The problem with the above experiments does not lie in their simplicity—or at least not solely in that. The distance between the capsaicin-laced footpads of mice and Proust’s madeleines indeed appears chaotic. How is it possible for such experiments to have the slightest relation to the descent into the labyrinth of childhood memories?

More significant, however, seems to be the fact that the experimental labyrinth in which mice are tested and that in which a human mind dreams lie on different levels. An experimental labyrinth, by its very nature, places the living organism in an anxiety-inducing condition, resembling more of a stress test. It takes considerable doses of psycho-intellectual distortion and malformed ideology to consider anxiety-provoking situations as the normal relationship of the organism to its environment. And yet. Laboratories studying “memory” around the world are based, whether explicitly or implicitly, on this assumption. An assumption that, of course, is not new. Georges Canguilhem was already writing in the 1950s:10

“An animal within an experimental condition is an animal within an abnormal condition, within a condition that it does not need based on its own norms. It has not chosen this condition; it has been imposed upon it. An organism therefore never equals the theoretical sum of its possibilities.

…

The relationship between the living and its environment is established as a dialogical relationship (Auseinandersetzung), in which the living enters with its own, specific norms for evaluating situations. It is not a matter (as one might think) of a relationship of opposition or conflict.

…

A healthy life, a life full of self-confidence in its existence and values, is a flexible life, full of elasticity, almost soft. The situation in which the living is subjected to the external demands of its environment is what Goldstein considers to be the archetype of the destructive situation. And this is the condition of the living in the laboratory. Of all possible relationships, those between the living and its environment, as examined experimentally and objectively, are those that have the least meaning; they are pathological relationships.”

And if the laboratory falls short of reality in critical and essential aspects, then the escape route can be disarmingly simple: as bad as it gets for reality; it suffices for it to start reflecting the laboratory (or the factory, which does not differ much) and its conditions more faithfully. A goal that is sometimes achieved more easily than many would assume: by simply handing out smartphones to the underlings…

Behind such methodological failures, however, certain problematic ontological assumptions are also hidden. How convincing would someone be who claimed that the game of football could be understood by studying the ball alone exhaustively: its weight, its shape, its aerodynamic behavior? And that all that is needed for a full understanding is money, more money for more accurate equipment and brilliant researchers. No one denies that the physical characteristics of the ball may significantly affect the way a football match is played. Everyone, however, realizes that the essence lies in the players and, more specifically, in the dynamics that develop between teammates and opponents. Even if the ball were cubic, one could still talk about football; perhaps not exactly the same football, but about football. For the “sphairo-logos” of our thought experiment, however, such a change would automatically eliminate its object as well (perhaps someone should pursue an additional degree in “cube-logos”). By analogy, the vast majority of today’s neuroscientists position themselves structurally against memory (and consciousness) just as the sphairo-logos positions itself against football, believing that the royal road to decoding the mnemonic code will be found somewhere within the nervous system and more specifically somewhere within the brain. One only needs to carefully study the brain and all the secrets of consciousness will be revealed to them.

Just like so many other scientific ideas, this one regarding the centrality of the nervous system and the brain in the formation of consciousness did not arise exactly from empirical data. The path followed was rather the reverse: first it was accepted, for reasons not strictly scientific, that the brain is the seat of consciousness, and then began the production of data that “confirmed” this belief (and not exactly a hypothesis). The revaluation of experience and nature that took place during the European Enlightenment played a key role in this process11. From the moment sensory experience ceased to be treated as epistemologically unreliable (mental ideas were considered clearly more distinct and orderly) and morally insignificant (or even dangerous), it immediately acquired a new authority. Not only did it stop being considered a source of confusion, but in many cases it became the only essentially legitimate path to understanding the world. As a direct result, the sensory organs of the human body, as well as the nerves that originate from them, acquired a new value as objects of study. The Platonic-Christian Mind that ascends and descends the scale of quasi-geometric Ideas was replaced by the neural Mind, the brain and its signals that travel through the nerves.

But if the brain became the organ in which the “spirit” could finally be entrusted, this meant that the self also became locatable. The self does not diffuse itself through the web of its social relations, but contracts and collapses like a black hole into an almost point-like being, inwardly folded and primarily detached from its environment.12 Only secondarily does it unfold outward to establish relations in the form of contracts. This phobic syndrome toward the external world sometimes had extreme consequences (as in the case of Locke), going so far as to regard even the body as something almost external to the self and therefore as an asset that its owner could dispose of however he wished (e.g., by selling his labor power). This was a restructuring and reconfiguration of the concept of the self that was “necessary” for liberalism itself to acquire philosophical and scientific legitimation.

The relationship between neuroscientific theories and liberalism seems not to have been coincidental, but rather to have endured over time. Although the brain has not been dethroned, specific theories concerning it have undergone a mutation toward directions eerily similar to those toward which liberalism has moved. The latest major trend (which has been ongoing for decades now) in the world of neuroscience goes by the name “plasticity,” referring to the high degree of adaptability that the brain exhibits—hence the particular interest in learning behaviors and memory mechanisms. Functionally, therefore, the brain is no longer perceived as an organ with a fixed structure. Depending on its functional needs, this structure can change both at the level of synapses—synapses that are frequently activated tend to strengthen, while those that fall into disuse disappear—and at the level of anatomical substrates; for example, if nerves carrying visual signals are connected to the brain’s auditory cortex, it will ultimately learn to process visual signals, even though it formally processes auditory ones. The plastic brain is thus conceived as a set of differentiated yet reorganizable mechanisms, continuously adapting to its external environment and its stimuli.

The result? The self, from a hyper-dense and compact black hole, begins to evaporate into a flexible and colorful bubble. The reorganization of brain structures also implies the ability for infinite analysis and resynthesis of the self until it becomes something illusory. With the same movement, however, the fragmentation of the sense of self inevitably leads to a decay of the sense of reality. Reality is only the continuously suspended and permanently temporary “constructs” of the brain, whatever it chooses to process from the information that reaches it through the sensory organs. There is no one reality; there are only interpretations of reality. At best, reality simply becomes a convention agreed upon between subjects, the result of a legal act.

Under different circumstances, such a fascination with the self could even be considered a work of art. Under the conditions of neo-liberal capitalism of recent decades, however, the dissolution of the sense of self has almost perversely signaled the hyper-amplification of the importance of the Ego. If the brain and the self are infinitely reconstructible and there is no stable and immovable internal point of resistance against the demands of the environment, then the path of continuous (self-)improvement13 immediately opens up. Eyes that capture ultraviolet radiation, ears that catch high-frequency sounds, and third or fourth hands can only be counted as upgrades of a permanently obsolete self. The pyramid of the Ego is built upon the guilt syndromes of a self in permanent crisis; or, otherwise, in a permanent condition of testing against an environment perceived as threatening…

What must definitely be noted here is that both the performative tailoring of reality and the (self-)tailoring of subjects does not aim merely at an increase in productivity within the work environment. The obsession with efficiency has now invaded even the most intimate aspects of daily life. There is no non-productive life outside of work; every moment is recorded, every choice is weighed in averages, and every emotional reaction is factored into the data of someone’s model. If the self has dissolved, the Ego can maintain whatever coherence it has only insofar as it functions as a producer and transmitter of a continuous data stream and as a malleable receiver of advertisements, recommendations, advice, and ultimately, orders. A stream that must be as uninterrupted as possible14.

From this perspective, the importance that Silicon Valley companies place on developing new neurotechnology tools and devices can be better understood15. It is known that a tool, in the hands of a skilled operator, can become second nature, used without the operator even being consciously aware of it. In fact, only when the operator stops feeling the tool as resistance and no longer needs to actively think about using it can they truly unleash their full potential. Nevertheless, no tool can ever become a person’s first nature. There will always remain some distance, however small, between the tool and its user. Among other goals, the new marvels of neurotechnology aim to continuously reduce—and, if possible, ultimately eliminate—this distance. Devices that will be directly attached to a hacked nervous system will provide unlimited sources of data, collected without guilt or inconvenience16.

No matter how microscopic the nano-devices for hacking the nervous system might (will) be, functionally they will resemble oil pumps more. However, setting up data pumps, just like oil pumps, presupposes a desertification. They presuppose the endless fields of internal deserts where the overweening Egos struggle to survive, dragged by all kinds of specialized fools who play as clowns in a poorly made, dystopian farce-comedy that isn’t funny at all.

Separatrix