DARPA needs no special introduction: it is the tip of the technological spear of the American military-industrial complex. Although it is at the forefront of the bioinformatics revolution, the research it conducts and the applications emerging from its laboratories seem so futuristic that the general perception of DARPA evokes more of a movie production studio for superhero films than a government agency. Yet its work is as solid and concrete as the intravenous doses of mutated cells served up for “salvation”; what seemed unthinkable yesterday is today already a universal reality.

DARPA’s reference to any combination with the “war against the coronavirus” certainly constitutes sacrilege, since the former is a dark service with warlike plans and intentions, while the latter is conducted by enlightened representatives of science with the goal of saving humanity. However, history does not begin in December 2019, and fortunately evidence from the pre-covid era still exists that challenges the modern orthodoxy of hygiene coups.

The article we present in translation below was published by a mainstream source in November 20181 and by no means would we judge it as denunciatory, nor even critical. It rather expresses “concerns,” while not failing to make a generous presentation of the service, its achievements and research, always based on the statements of its own employees, as a controlled PR presentation. What it seeks, with references to its mysterious biotechnological plans, is not to condemn but to inspire awe; and to define the kind of criticism that is allowed: what they are creating is the post-human, but the issue is that it should not be misused. If the author knew today’s philology, he would surely add this too: the benefits outweigh the consequences…

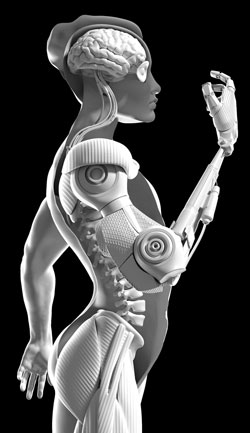

However, there are points that deserve our utmost attention, especially now under conditions of violent biotechnological restructuring. The body is a prison, and biotechnologies, as designed by state laboratories, aim to free us from its bonds. The body is what confines us, therefore it must be dissected, controlled, nullified, reconstructed, and reconfigured as a supplement to advanced bioinformatic systems. The augmented human is a better human, and in his confrontation with the non-technologically-restructured human, the latter will prove inferior. The human with the third or fourth arm, the third ear, bat hearing, and vision in the ultraviolet (sic) is the future of our species. The hyper-soldier who stands ready for battle and awake 24/7, has an integrated pharmacy, his bodily functions are controlled by computer, and directs weapons with his brain, is the guarantee of sovereignty.

In the 2000s, according to the article, DARPA underwent a major crisis due to the negative impact caused by the disclosure of its plans for autonomous weapons systems. The result was a major restructuring both in the type of oversight that would be exercised over the agency and in the way its research and results would be implemented. On one hand, Congress theoretically banned any research on the “augmented human,” but whether the outcome might accidentally or inadvertently lead to that is another story (referred to precisely as a “directive”). On the other hand, they redesigned the stated goal of their neurotechnology research to ostensibly focus on a more limited field: wound healing and disease treatment. Our work has nothing to do with weapons and war, officials claimed, it has to do with therapy and healthcare… DARPA’s history includes many episodes where new technologies are introduced through appealing applications, while the real and more troubling purposes are concealed (again, from the article).

Do we know of such examples, biotechnologies developed by DARPA and introduced through “attractive applications,” as “therapy and healthcare”? Under today’s conditions, the answer should be immediate and straightforward. DARPA generously funds a newly established pharmaceutical company, Moderna, which had not registered even a single drug patent, assigns to it the mRNA research it had conducted over the years, allows it to develop a genetic engineering platform (as the company itself named it), all of this before covid, and subsequently markets it as a “vaccine” against a coronavirus, thus ultimately becoming the biotechnological spearhead of the new totalitarianism.

Harry Tuttle

The Pentagon wants to turn the brain into a weapon.

What could go wrong?

Who would disagree;

“Today I would like to share with you an idea that I am very passionate about,” the young man began to say. “Think about this. Throughout human history, the way we have expressed our intentions, the way we have manifested our goals, the way we have expressed our desires, has been limited by our bodies.” Pointing to his own body, he continues. “We are born into this world with this. With whatever nature or fate gives us.”

Then his speech took a somewhat different direction. “Now we have developed many interesting tools over time, but fundamentally the way we work with these tools is through our bodies… Here’s a situation I’m sure you all know very well – your frustration with your mobile phones, right? It’s just another tool, right? And we still communicate with these tools through our bodies.”

Then he made a small leap. “I will claim before you that these tools are not that smart. And perhaps one of the reasons they are not that smart is because they are not connected to our brains. Perhaps, if we could connect these devices to our brains, they would gain an idea of who our goals are, what our intentions are, and what it is that unsettles us.”

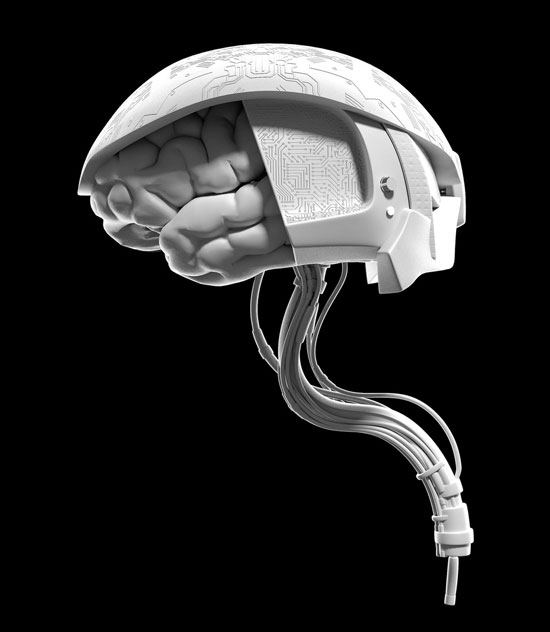

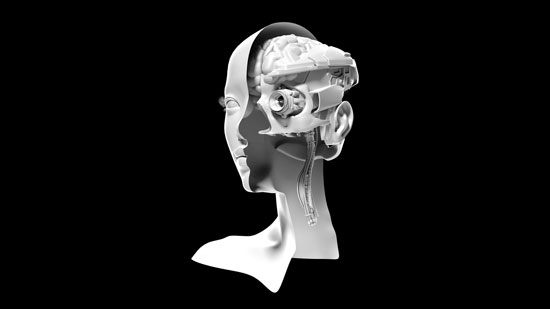

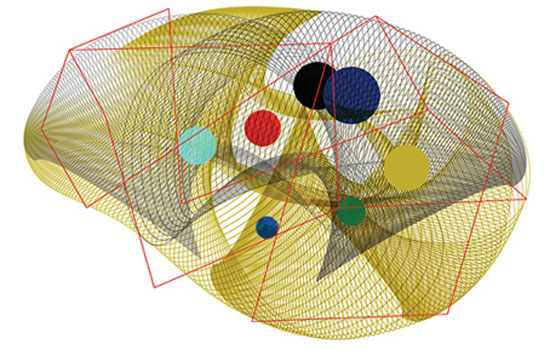

This is the introduction of a speech titled Beyond Bionics2 by Justin C. Sanchez, then an assistant professor of biomedical engineering and neuroscience at the University of Miami and a member of the “to cure paralysis” project. He was speaking at a TedX event in Florida in 2012. But what comes after bionics? Sanchez described his work as an effort “to understand the neural code,” which would evolve to the point of placing “electrodes the diameter of a human hair in the brain.” When we do this, he argued, we will be able “to listen to the brain’s music” and “hear someone’s motor intentions” and gain an image “of the goals and expectations” and then “we will begin to understand how the brain encodes behavior.”

He then explained that “with all this knowledge, what we are trying to do is to create new medical devices, new implantable chips for the body, which can be encoded or programmed based on these different aspects. You might wonder what we are going to do with all these chips. The first ones to receive such technologies will be paraplegics. It would be something that would make me happy at the end of my career, if I could help someone get up from a wheelchair”.

“The people we are trying to help should never be imprisoned in their bodies. And today we can design technologies that will help them be liberated from them. This is what guides me every day from the moment I wake up. Thank you,” he concluded his speech by sending a kiss to the audience.

A year later, Sanchez went to work at DARPA, the Pentagon’s research and development service. At DARPA, he now oversees all research related to treating and enhancing the human mind and body. And his ambitions include much more than helping people with mobility problems get out of wheelchairs – much more.

For decades, DARPA has been pursuing the goal of merging human beings with machines. A few years ago, when the prospect of developing mind-controlled weapons negatively impacted the agency’s public image, officials resorted to characteristic ingenuity. They redesigned the stated goal of their neurotechnology research to ostensibly focus on a more limited field: wound healing and disease treatment. “Our work has nothing to do with weapons and war,” officials claimed, “it has to do with therapy and healthcare.” Who could possibly object? But even if these claims were true, such developments would carry extensive ethical, social, and even metaphysical implications. Within a decade, neurotechnology could trigger social disruptions on such a scale that smartphones and the internet would seem like gentle ripples in the ocean of history.

But perhaps most concerning is that neurotechnology overturns long-standing historical answers to this crucial question: what is a human being?

High risk – high reward

In his proclamation in 1958, President Eisenhower supported that “in research and development the USA must constantly look ahead in order to anticipate the unthinkable weapons of the future.” A few weeks later, his administration created the Advanced Research Projects Agency, an independent service that reported directly to the Secretary of Defense. This move had been prompted by the successful Soviet launch of the Sputnik satellite, and the agency’s initial mission was to accelerate the entry of the USA into space.

In the following few years, ARPA’s mission expanded to include research on “human-computer symbiosis” as well as a secret program of mind control experiments under the codename Project Pandora. There were various strange attempts at the time that even reached experiments on moving objects from a distance using only thought. In 1972, in a crisis of sincerity, the word Defense was added to the name and the agency became DARPA. Following its mission, DARPA funded research that led to technologies which radically changed the nature of battle (such as stealth aircraft and drones) and influenced the lives of millions of people (with voice recognition technologies or GPS). Certainly, its most famous creation is the internet.

The agency’s policy for what it called “high-risk, high-reward” research resulted in funding a parade of follies. The Seesaw program, the epitome of useless research during the Cold War, had in the works a “ray gun” that would be deployed in case of a Soviet attack. The idea was to trigger a series of nuclear explosions beneath the Great Lakes, creating a massive underground reservoir. The lakes would then be drained within 15 minutes, generating the electrical energy to activate the ray weapon. The ray would be accelerated through tunnels hundreds of kilometers long (also to be constructed using nuclear explosions) to gain enough power to reach the atmosphere and shoot down Soviet missiles in the air. A similar example comes from the Vietnam War era, when DARPA attempted to build the “Cybernetic Anthropomorphic Machine,” a jungle vehicle that officials ultimately named the “mechanical elephant.”

The different and often conflicting goals of DARPA scientists and their superiors in the Department of Defense led to a dark, symbiotic research culture—”free from standard bureaucratic oversight and unimpeded by the constraints of academic criticism,” as Sharon Weinberger wrote in her recent book, The Imagineers of War. According to Weinberger, the history of DARPA includes many episodes where new technologies are introduced through attractive applications, while the actual and more troubling purposes are concealed. At DARPA, the left hand knows, but doesn’t even know what the right hand is doing.

The agency looks deceptively small in size. Only 220 employees, supported by approximately a thousand contractor workers, punch in every morning at DARPA’s headquarters, an unremarkable glass and steel building in Arlington, Virginia, across from the Washington Capitals’ training center. About 100 of the employees are program managers – scientists and engineers whose job is to oversee approximately 2,000 outsourcing agreements with companies, universities, and government laboratories. The essential workforce of DARPA actually amounts to tens of thousands. The budget, the one officially announced, reaches 3 billion dollars, and has remained unchanged at this level for an unimaginably long time for a government agency – the last 14 years.

The Biological Technologies Office, created in 2014, is the newest of DARPA’s six core departments. This is the office that Sanchez leads. One of the office’s goals is “to restore and maintain warfighter capabilities” in various ways, many of which focus on neurotechnologies—the application of engineering principles to the biology of the nervous system. For example, the Restoring Active Memory program develops neuroprosthetics—microscopic electronic components implanted into brain tissue—and aims to modify memory to compensate for traumatic brain injuries. Does DARPA conduct secret biological programs? In the past, the Department of Defense had done such things, with tests on humans that were questionable, unethical, and, as many have argued, completely illegal. The Big Boy protocol, for instance, compared radiation exposure among sailors who worked above and below deck on warships, without ever informing the sailors that they were part of an experiment.

A year ago I directly asked Sanchez whether there are DARPA programs, especially in neurotechnologies, that are classified. His answer was “we should leave this issue, because I can’t answer either way.” When I rephrased the question, addressing him personally (“are you personally involved in any classified neurotechnology program?”) he looked me in the eyes and answered “I don’t do any classified work that has a neurotechnology endpoint.”

His remarks may be cautious, but they are not rare. Sanchez appears with some regularity at public events (there are relevant videos on DARPA’s YouTube channel) to present a cheerful plethora of good news regarding DARPA’s tested applications – for example, brain-controlled prosthetic hands for soldiers who have lost limbs. Occasionally, he also refers to some of his more distant inspirations. One of these is the process, via computer, of transferring knowledge and thoughts from one person’s mind to another.

“We are trying to find ways to say yes”

Pharmacology and biology had little interest for DARPA until the 1990s, when biological weapons were deemed a threat to American national security. The agency made a significant investment in biology in 1997, when DARPA created the Controlled Biological Systems program. Zoologist Alan S. Rudolph led this extensive effort to bridge the artificial with the natural world. As he explained to me, the goal was “to increase, at will, the rate of connection, or intercommunication, between living and non-living systems.” The questions that concerned him were of the kind “can we unlock brain signals related to movement in such a way as to allow control of something outside the body, such as a prosthetic hand or leg, a robot, a smart home – or send this signal to someone else and have them receive it?”

Human enhancement became a priority for the service. “Soldiers without natural, physiological, and perceptual limitations will be the key to survival and operational dominance in the future,” predicted Michael Goldblat, who was a scientific and technological officer at McDonald’s before joining DARPA in 1999. To enhance human ability to “control evolution,” he organized a series of programs with names that seemed to come out of video games or sci-fi movies: Metabolic Dominance, Persistence in Battle, Continuous Assisted Performance, Enhanced Perception, Military Performance Apex, Brain-Machine Interface.

The programs of that era, as Annie Jacobsen described in her 2015 book The Pentagon’s Brain, often veered into the realm of mad science. For example, the Persistent Aquatic Living program aimed to create a “24/7 soldier” who could operate continuously without sleep for up to a week. (“The measure of our success,” a DARPA official said of these programs, “is that the International Olympic Committee has banned whatever we do”).

Dick Cheney had been enthusiastic about such research. In the summer of 2001, a broad spectrum of programs for “super-soldiers” was presented to the vice president. His enthusiasm contributed to the push that the Bush administration gave to DARPA—at a time when the agency’s base was shifting and academic science was giving way to the “innovations” of the tech industry. It was then that Tony Tether, whose entire career had moved between the technology industries, defense industries, and the Pentagon, became director of DARPA. After 9/11, the agency announced a plan for a surveillance program named Total Information Awareness, whose logo featured an all-seeing eye emitting rays that scanned the globe. Reactions were strong, and Congress launched an investigation into DARPA’s activities, suspecting Orwellian practices. The head of the program—Admiral Poindexter, who had been indicted for the Iran-Contra scandal under Reagan—eventually resigned in 2003. The controversy brought attention to the agency’s discreetly held programs on super-soldiers and the fusion of mind and machine. Revelations about these research efforts caused even greater concern, and ultimately, the new director, Alan Rudolph, also found his way out the door.

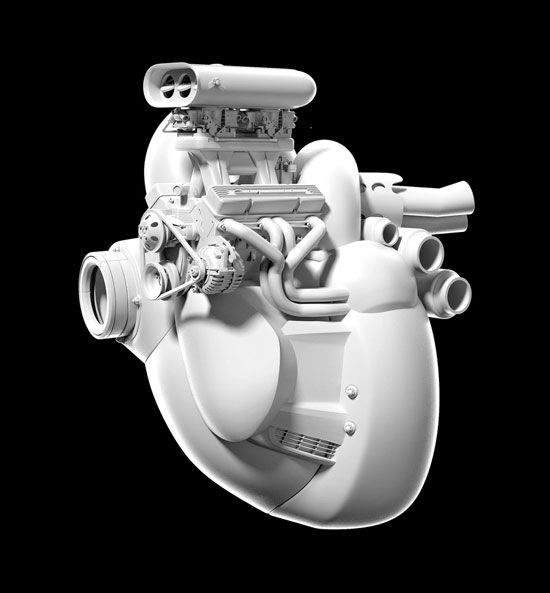

At this stage of the crisis, DARPA called upon Geoff Ling, a neurologist-intensivist and then-active Army officer, to participate in the Defense Sciences Office. (Ling continued his work at the Biological Technologies Office when it was spun off from Defense Sciences in 2014). When Ling was going through interviews for his first position at DARPA, in 2002, he was ready for deployment to Afghanistan and had very specific needs in mind for the battlefield. One such need was an “on-demand pharmacy” that would eliminate the need for a multitude of pills and capsules and replace it with a kit that would formulate active substances into lighter and smaller forms ready for administration. This plan eventually became a DARPA program. The agency’s tactic of supporting even the most audacious projects gave momentum to Ling, who fondly remembers how his colleagues would say “we try to find ways to say yes, not ways to say no.” When Rudolph stepped down, Ling took over his position.

Ling recalls the first lesson about the Office of Defense Sciences that he specifically learned from Rudolph: “Your brain tells your hands what to do. Your hands are essentially the brain’s tools. We are tool users – that is what humans are. Humans want to fly, they build an airplane and fly. Humans want to have recorded history and they make a pencil. Everything we do is because we use tools. And the ultimate tools we have are our hands and our feet. Our hands allow us to work with the environment and make things, and our feet take us where the brain wants to go. The brain is the most important.”

Ling connected the idea of brain supremacy with his own battlefield experience. He asked himself “how can we liberate humanity from the constraints of the body?” The program for which Ling became most known is called Prosthetic Revolution. Since the time of the Civil War, says Ling, the prosthetic hand given to most amputees was little more advanced than a hook, and this was not without risks. “Try to do your morning hygiene with this crude tool and you’ll end up needing a proctologist every day.” With the help of his colleagues at DARPA and academic and business researchers, Ling and his team built something that until recently was unthinkable: a brain-controlled prosthetic hand.

No other invention since the internet has brought better publicity to DARPA like this one. The milestones in its development were welcomed with enthusiasm. In 2012, the 60 Minutes show featured a paralyzed woman, Jan Scheuermann, eating a piece of chocolate using a robotic arm that she controlled herself through an implant in her brain.

But DARPA’s work to repair damaged bodies was just one point on a road that led somewhere else. The agency had always had a much broader mission and in a 2015 presentation, a program director – recruited from Silicon Valley – described this mission: “to free the mind from the constraints even of the healthy body.” What the agency learns from therapies it uses in enhancement. The mission is to make human beings something other than what they are now, with powers beyond those with which we are born and beyond those we can physiologically acquire.

The internal processes at DARPA are complex. The goals and conditions of its research projects shift and evolve in the manner of a strange, semi-conscious broader game. The boundaries between “therapy” and “enhancement” blur; and one must not forget that D is the first letter in DARPA’s name. A year and a half after the video showing Scheuermann offering chocolate to herself, DARPA produced another video with her, in which the brain-computer interface was connected to an F-35 flight simulator and she was flying the aircraft. Later, DARPA presented this video at a conference titled Future of War.

Ling’s efforts were continued by Justin Sanchez. In 2016, Sanchez appeared at DARPA’s “demo day” alongside Johnny Matheny, whom the agency described as the first “osseointegrated” amputee with an amputated hand—the first person with a prosthetic hand directly connected to the bone. Matheny demonstrated what was then DARPA’s most advanced prosthetic hand. “I can sit here all day lifting a 20-pound ball until the batteries run out.” The next day, Gizmodo [a technology content portal] had this headline for its related report: “DARPA’s Mind-Controlled Hand Will Make You Wish You Were a Cyborg.”

Since then, DARPA’s work in neurotechnology has demonstrably expanded to include “the broader aspects of life,” Sanchez explained to me, “beyond the people in the hospital who need it for therapeutic reasons.” The logical evolution of all this research is the creation of human plasmas that are even more advanced, based on specific technological criteria. New and improved soldiers are necessary and sought after by DARPA, but they are simply a window that shows us the life that lies ahead of us.

Beyond the Horizon

Think about memory, Sanchez told me: “Everyone wonders what it would be like if we gave memory a boost of 20, 30, 40% – put in whatever number you want – and how that would change things.” He speaks about enhancing memory through neural interfaces as an alternative form of education. “School, in its most fundamental form, is a technology we as a society have developed to help our brains do more,” he says. “In different ways, neurotechnology uses other tools and techniques to help our brains become the best they can be.” One such technique was described in a 2013 paper, for a study in which researchers from Wake Forest University, the University of Southern California, and the University of Kentucky participated. The researchers performed surgical procedures on 11 mice. An electronic array with 16 stainless steel wires was implanted in each mouse’s brain. After they recovered from surgery, they were divided into two groups and underwent a training period, with one group being trained more than the other.

The less educated group learned a simple task, which involved how to procure a quantity of water. The more educated group learned a more complex procedure of the same task – to procure the water these mice would have to persistently press some levers with their snouts and despite delays that were meant to confuse them, wait for the delivery of the water. When the more educated group perfected this task, the researchers extracted the neural patterns that had been recorded in the brains of the mice – the memory of how to perform their complex task – from the implanted electronic arrays into a computer.

“What we did next was take these signals and pass them to the animals that were stupid,” Ling explained at a DARPA conference in 2015. That is, the researchers took the neuronal stimulation patterns that encoded the memory of executing the most complex mission and had been recorded in the brains of the most trained mice, and transferred these patterns to the brains of the less trained animals. “And these stupid animals succeeded. They were able to execute the mission fully. For these mice, we reduced the training period from 8 weeks to a few seconds.”

“They could infuse memory using the precise neural codes for specific abilities,” Sanchez claimed. He believes that this experiment constitutes the fundamental step toward “adding memory.” Although many researchers dispute the findings—warning that, in reality, it cannot be that simple—Sanchez is certain: “If I know the neural codes of one person, can I give these codes to another person? I think we can.” Under Sanchez, DARPA has funded experiments on humans at Wake Forest University in western California and the University of Pennsylvania, using similar mechanisms in analogous parts of the brain. These experiments did not transfer memory from one person to another, but gave individuals a memory “boost.” Implanted electrodes recorded neural activity related to pattern recognition (at Wake Forest and USC) or memorizing words (at Penn) in specific brain circuits. Subsequently, electrodes re-fed these neural activity recordings back into the same circuits, as a form of enhancement. The result in both cases was a significant enhancement of memory recall.

Doug Weber, a neuroengineer at the University of Pittsburgh who recently completed a four-year stint at DARPA as a program director alongside Sanchez, is a skeptic of memory transfer. “I don’t believe in the infinite limits of technological advancement,” he tells me. “I think there will be certain technological challenges that will be impossible to answer.” For example, when scientists place electrodes in the brain, these devices will eventually fail—after a few months or years. The most intractable problem is blood loss. When a foreign body is placed in the brain, says Weber, “the same process repeats itself over and over: injury, bleeding, healing, and back to the beginning. When blood leaks into the brain, the activity of cells in these areas drops dramatically and the cells eventually weaken.” More than a fortress, the brain prevents invasion.

Even if the interface problems that constrain us did not exist, Weber continues, he still does not believe that neuroscientists will be able to implement the scenario of adding memory. Many people think the brain is a computer, Weber explains, “where information goes from A to B to C as if it were a modular process. There are certainly such processes in the brain, but by no means are they as specific as in a computer. All the information is everywhere all the time. It is so widely distributed that achieving a usable degree of connectivity with the brain is beyond feasible at this time.”

Peripheral nerves, in contrast, transmit signals in a more articulated and serial manner. The longest peripheral nerve is the vagus nerve. It connects the brain to the heart, lungs, gastrointestinal tract, and others. Neuroscientists understand the relationship of the brain to the vagus nerve more clearly than they understand the complexities of memory formation and recall between neurons and the brain. Weber believes that we can stimulate the vagus nerve in ways that enhance the learning process – not by transferring experiential memories, but by sharpening proficiency in specific abilities.

To investigate this hypothesis, Weber launched a new program at the Biological Technologies Office, named Targeted Neuroplasticity Training (TNT). Research teams at seven universities examined whether vagus nerve stimulation could enhance learning in three areas: perception, monitoring/recognition, and language. The team at the University of Arizona includes an ethicist whose role, according to Weber, is “to look beyond the horizon to anticipate potential challenges and conflicts that might arise” regarding the ethical dimensions of the program’s technology “before we unleash the genie from the bottle.” During one of TNT’s early meetings, the group of researchers devoted 90 minutes to discussing the ethical questions of their work—and this was the beginning of a weighty discussion that would expand to include others and continue for a very long time.

The directors of DARPA refer to the potential consequences of neurotechnology using the acronym ELSI, a term that had been first used for the Human Genome Project. The initials stand for “ethical, legal, social implications.” The person who led the discussion among the groups was Steven Hyman, a neuroscientist and psychiatrist at MIT and on the board of directors of Harvard, and former head of the National Institute of Mental Health. When I discussed with him his work on DARPA’s programs, he noted that one issue that requires special attention is “crosstalk.” A human-machine interface that does not simply “read” someone’s brain but also “writes” to someone’s mind will almost certainly cause “crosstalk between the networks we target and the networks involved with what we could call social and ethical feelings.” It is impossible to predict the consequences of such crosstalk in “conducting warfare” (this example was given by Hyman) and, much less naturally, in daily life.

Weber and a DARPA representative summarized some of the questions raised by researchers during the ethics discussion: Who will decide how this technology will be used? Will a superior be able to impose its use on subordinates? Will genetic tests be used to determine how receptive someone will be to neuroplastic training? Will such tests be voluntary or mandatory? Could the results of such tests lead to discrimination in school or at work? What will happen if this technology affects moral or emotional perception—or one’s ability to distinguish right from wrong or to control their own behavior?

Recalling the ethics discussion, Weber commented that “the main thing I remember is that we ran out of time.”

We can turn anything into a weapon

In her book The Pentagon’s Brain, Annie Jacobsen argues that DARPA’s neurotechnology research, such as prosthetic limbs and brain-machine interfaces, is not what it appears to be: “It is possible that DARPA’s primary goal in developing prosthetics is to give robots, not humans, better hands and feet.” Geoff Ling dismissed this claim when I presented it to him (he had not read the book). His response was: “When we talk about such things and people look for nebulous things, I always tell them ‘do you really believe that the army your grandfather served in, that your father served in, has transformed into the army of the Nazis or the Russians?’ Everything we did in the Revolutionizing Prosthetics program – everything we did – is published. If we were actually building autonomous weapons systems, why would we proceed with publications and let our competitors read them? We didn’t hide anything. We didn’t hide a single thing. And you know what? This means we didn’t do it just for America. We did it for the whole world.”

I started telling him that publishing research does not prevent its misuse. But the terms of use and abuse overlook a larger issue at the heart of any substantive discussion on neurotechnology/ethics. An augmented human being – a human entity that will have a neural interface with a computer – will still be human, in the way humanity has been understood throughout history? Or will such a person be a different kind of being?

The American government has placed limits on DARPA’s ability to conduct experiments on enhanced human capabilities. Ling says his colleagues had spoken about a “directive”: “Congress was very specific. They don’t want us to create a super-soldier.” Under no circumstances should this be the publicly stated goal, Congress seems to say, but if we happen to reach that point by accident – that’s another story. Ling’s vision remains strong. He says: “If we give you a third eye and that eye can see in ultraviolet, it will be integrated into everything you do. If I give you a third ear and it can hear high frequencies, like a bat or snake, then you would incorporate all these senses into your experience and use them to your advantage. If you can see in the dark, you’re better than someone who can’t see in the dark.”

Enhancing the senses to gain superior advantage – this language evokes weapons systems. Such capabilities could certainly have military applications, Ling admits – “after all, we can turn anything into a weapon, right?” – before rejecting the idea and returning to the official line: “No, all this has to do with enhancing human capabilities” in a way he compared to military training and civilian education, and justified in economic terms.

“Let’s say I give you a third hand, and then a fourth, so two additional hands,” he says. “You’ll be more capable, you’ll do more things, right?” And if you can control four hands as seamlessly as you can two now, he continues, “you’ll actually do twice the volume of work you usually do. It’s that simple. You increase your productivity to do whatever you want.” I begin to form the image of him working with four hands and ask him “and where does this end?”

“It will never end,” says Ling. “I mean, it will keep getting better and better. What DARPA does is provide a fundamental tool that others can take and do incredible things with; things we can’t even imagine today.”

Judging from what he said next, though, the things DARPA is thinking about go far beyond what it officially announces publicly. “If a brain can control a robot that looks like a hand,” says Ling, “why can’t it control a robot that looks like a snake? Why can’t that brain control a robot that looks like a large jelly-like sphere that can turn at angles, go up and down, and penetrate objects? I mean, someone will find an application for it. They couldn’t do it now, because they can’t make that sphere. But in my world, with their brain directly connected to this sphere, the sphere becomes their embodiment. So they essentially become the sphere and can do anything that sphere can do.”

The fever of gold

The developing plans of DARPA are still at the edge of the proof-of-concept stage. But they are so close that they have attracted investments from some of the largest and wealthiest companies in the world. In 1990, during the first Bush administration, DARPA director Craig Fields lost his job because, according to some sources of the time, he had deliberately promoted business relationships with certain Silicon Valley companies, and the White House deemed these relationships inappropriate. However, since the second Bush administration, such sensitivities have faded.

Over time, DARPA became something of a talent farm for Silicon Valley. Regina Dugan, who had been appointed DARPA director by Obama, subsequently took over as head of Google’s Advanced Technology and Projects division, where she was followed by other DARPA employees. She then jumped to the position of head of research and technology at Facebook (although she has since left there as well).

DARPA’s neurotechnology research has been affected in recent years by the headhunting that large companies engage in to search for staff. Doug Weber told me that some DARPA researchers have been “poached regularly” by companies such as Verily (a subsidiary of Alphabet, Google’s parent company, which deals with biotechnology) which, in collaboration with the British pharmaceutical group GlaxoSmithKline, created the company Galvani Bioelectronics, aiming to bring neuron-modulating devices to market. Galvani refers to its activity as “bioelectronic medicine,” in order to cultivate an image of familiarity and trust. Ted Berger, a biomedical engineer at the University of Southern California, who had worked on research into memory transfer between mice, worked as chief scientific officer at the company Kernel, which plans to create “advanced neuron interface systems for treating diseases and disorders, revealing the mechanisms of the mind and extending perception.” Elon Musk has approached DARPA researchers to work at his company Neuralink, which is said to be developing an interface system called a “neural lace.” Building 8 [this is what the Facebook department dealing with biotechnology is called] is also working on neural system interfacing. In 2017, Regina Dugan had announced that 60 engineers are working on a system that will allow users to type 100 words per minute “directly from their brain.” Geoff Ling himself is a member of Building 8’s advisory board.

Discussing with Justin Sanchez, I made the assumption that if his ambitions are realized, he could change everyday life in a more fundamental and lasting way than Zuckerberg of Facebook or Dorsey of Twitter. He might have felt uncomfortable hearing his name in such a sequence, but the reference did not alienate him. Recalling a remark he had once made about the “broad acceptance of neurotechnology,” but with “appropriate controls to ensure it’s done the right way,” I asked him to describe to me what that right way could be. Had he ever met any member of Congress who had any good ideas about the legal and regulatory rules that would define the field of the emerging neurotechnology industry?

He avoided answering (“DARPA’s job is not to define or even suggest such things”) and instead proposed that market forces would actually do more to shape the development of biotechnology than laws or regulations or deliberate policy choices. The market will take the reins: “As these companies develop and as they develop their products, they will need to convince people that what they’re making makes sense, that it helps people become a better version of themselves. And this process – this day-to-day development – will ultimately determine where these technologies will go. I think that’s the reality of how things will ultimately evolve.”

He seems completely unfazed by what appears to be the most worrying aspect of DARPA’s work: it’s not that it discovers what it discovers, but that the world is, so far, ready to consume it.

- This article was published in November 2018 in the print edition of the American The Atlantic. ↩︎

- https://youtu.be/VumV_5ojlxk ↩︎