Less than ten years have passed since the Internet of Things was making headlines and fueling the dreams of tech enthusiasts everywhere. Smart clothes that can gauge your mood and notify your phone, smart glasses that allow you to overlay reality with a second, personalized layer, smart, energy-efficient light bulbs tasked with carrying the burden of your ecological conscience by turning on only when you’re in the room or when you issue a command from your life’s remote control, otherwise known as your smartphone, smart coffee makers, genius cups, wi-fi enabled toilets, and the list goes on. All this new, “smart,” and illustrated life that universal connectivity of all things to the internet promised has proven, at least so far, to be merely a fantasy. But is this evidence of the Internet of Things’ failure? In one sense, the answer should be affirmative (again, at least for now), at least if one wants to take such promises at their face value. On the other hand, the Internet of Things could be considered as “failed” as any new car model from an automaker could be deemed a failure simply because drivers end up spending most of their time moving at a snail’s pace along Alexandras Avenue rather than gracefully gliding through open, vast expanses or serpentining roads winding up lush green mountains, as the related commercials would have us believe. The critical difference in the case of the Internet of Things, which will also determine the extent of its failure or success, is that it wasn’t simply an attempt to promote a product or even a range of products. What was largely promoted, or even imposed, was not just the shiny mirrors of smart devices, but the very idea of universal connectivity, the notion that information can be drawn from everything and that this information can be evaluated, utilized, and monetized.

There were many, far too many, perhaps the vast majority of subjects in Western societies, who seemed excessively eager to fall for the bait of all kinds of smart devices. To find themselves with the hook of universal connectivity lodged inside them, without perhaps even fully realizing the consequences of the position they have ended up in. The oceans of psycho-intellectual novocaine in which they swim daily (courtesy of social media platforms and subscription-based lobotomy platforms) do not, after all, leave them much room. The extent of this conscious retreat and the panicked surrender of positions once considered non-negotiable became evident, if nothing else, with the recent rollout of health certificate mandates. The helpless eagerness with which these subjects display the symbols of their undignified compliance with a paranoid regime (even for movements that are not necessary, such as those related to work or studies) represents a low point—but not the lowest—of political and aesthetic-moral degradation; at the other end of the drainpipe are those who assume the role of enforcer, often enjoying it, even if they do not openly admit it, perhaps not even to themselves (yet the tone of voice and body language remain undeniable witnesses). A wonderful social condition that allows microclimates and pockets to emerge everywhere, within which the fungi of petty authoritarian behaviors acquire the status of the self-evident: the teacher checks the students (as some malicious observer might say, “it’s not like it’s a brand-new role for teachers”), the shop assistant checks the teacher when the latter appears as a customer, the waiter checks the shop assistant when the latter goes to buy a coffee, and so on. Everyone is given the opportunity to assume the role of examiner; yet no one escapes that of the examined: in other words, the definition of a cannibalistic condition.

Not a trivial reminder: all of the above owe their “success” to a large extent to the fact that they benefit from mechanical mediation. The smartphones that promised the bloom of a life where everything would be available at the touch (or even before) of a button seem to first need to spread the manure of social barbarity in the form of mutual surveillance. It is obvious that without the ability to directly scan and identify a certificate, the entire “medical” monitoring regime would be discredited and moreover to such a degree that in the end it might collapse. But who would dare to rise up against such practices among those who, for the sake of whatever free “convenience,” have become spineless data donors through their various interconnected devices?

the body as a field of interventions

This intersection of medical “care” and surveillance with networking technologies is neither temporary nor occasional, even though it is often presented that way. It represents a fundamental axis of capitalist expansion towards the 4th industrial revolution, which unfolds periodically under various banners. Two of these are precision medicine, which tends to operate on a somewhat more tangible and grounded level, and post-humanism, for which no metaphysical vanity and no religious soteriology are foreign or out of place1. As if these were not enough, lately a third, similar banner has emerged: we refer to the so-called “Internet of Bodies.” We are not supporters of the inflationary creation of new terms for whatever a bureaucrat in some think tank or a researcher in search of new funding might come up with. The Internet of Bodies initially seems to be such a case of a term without a particular object, recycling old material. Even if this holds true to some extent, upon a second look the term appears to indeed signal a new turn in the relationships of bodily and electronic surveillance that deserves somewhat more informed attention. In contrast to precision medicine, the Internet of Bodies does not concern only health issues but potentially anything that can relate to the body, whether healthy or suffering. And as an extension, in a way, of post-humanism, it does not merely envision the biological body as perpetually upgradable, but simultaneously also as “open” to the outside world, as an inexhaustible source of information, as a node within a mega-feedback mechanism (the old, good dream of cybernetics).

What exactly is the Internet of Bodies? If the Internet of Things was the idea that every object in the world can now be equipped with sensors that have the ability to connect to the internet, the Internet of Bodies takes it a step further by treating the body itself as such an “object.” The body is now conceived as a “technological platform”2 upon which various kinds of devices can be developed and attached. More or less, this was also the purpose of the self-quantification and quantified self movement. For the Internet of Bodies, however, self-quantification constitutes only the first step. The integration of quantified and hacked bodies into a communication network, the quasi anatomical opening of them outward, even in the form of information flow, is the second step.

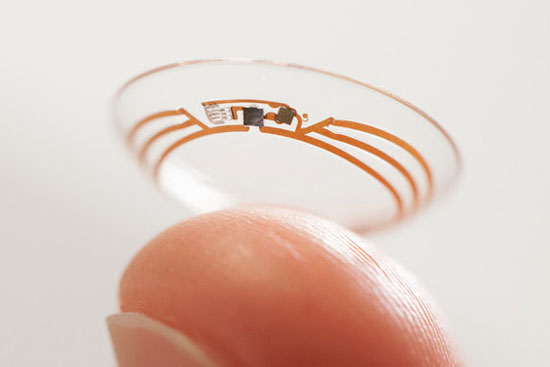

The first references to the term Internet of Bodies (at least based on our research) seem to go back to 2014 and were related to Google’s ambitions to develop such implantable devices, such as contact lenses containing nano-circuits and hair-sized antennas3. Despite its catchy and impressive nature, as a term it did not gain particular momentum in the immediately following years. Its broader establishment came in two phases, with a slight delay. First, it was used by American academic law professor Andrea Matwyshyn in an extensive article where she describes, categorizes and analyzes, often with a strongly critical attitude, these devices and the legal consequences their proliferation will have in the future4. This article has since become a constant reference point in all discussions related to the Internet of Bodies. Secondly, this particular term seems to be gaining popularity from 2020 onwards. The leading role has now been taken up by think tanks (such as RAND)5, World Economic Forum-type organizations6 and techno-scientific unions through their periodicals7. The fact that this term suddenly found itself on the most official lips and in the most official pens precisely during the period when the pandemic totalitarianism under the pretext of the coronavirus has put basic perceptions of the body and its autonomy into question cannot be considered simply coincidental. It is not a matter of temporal coincidence. Those who thought that coronavirus management concerned simply and only the virus itself and possible ways of dealing with it will soon learn that in reality it concerned all of their bodies. And the Internet of Bodies will be one of the terms of the polynomial on the basis of which the bodies of the subjects of western societies will be described and delimited.

The aforementioned text by Matwyshyn attempts, beyond providing a definition of the Internet of Bodies, to also make a first genealogical classification of related devices. As the first generation of Internet of Bodies devices, it refers to those that interact with the body while remaining external to it (body-external). Examples of such devices abound: from Google’s smart glasses that were withdrawn prematurely (but only temporarily, in our assessment) to all kinds of wearables for recording physical activity or even electronic skin devices that adhere to normal skin and take medical measurements of interest. It is important here to understand that many of these devices are not even considered medical devices and consequently their sale and use does not require approval from competent authorities. Nevertheless, they almost always have the capability to collect, process, and store the recorded data, far from users’ control. The issue of ownership, possession, and custody of this data remains in a legal vacuum, which of course does not prevent the companies behind them from proceeding with unprecedented ventures in primary accumulation of “digital capital,” given also the ignorance and apathy that users demonstrate toward such issues.

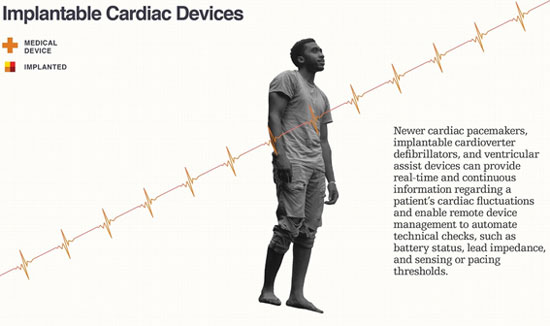

The second generation of IoB devices now refers to devices that, in order to function, must be “implanted” into the user’s body through invasive techniques that breach the body’s dermal boundaries (body internal). Cochlear implants (and generally devices for restoring sensory impairments), smart pacemakers, electronic pills with the ability to transmit information after ingestion, artificial organs (products of three-dimensional printers) are only a few examples. Even though they do not constitute something novel as ideas (conventional pacemakers have a long history), what now distinguishes them from their predecessors is their ability to connect to the outside world, firstly; and secondly, their ability to receive commands from the outside world and adjust their behavior accordingly, either based on such external commands or even spontaneously based on internal instructions, since many of them possess their own computational power, sometimes equipped with artificial intelligence algorithms8. Of course, it is understood that for this type of devices, the issue of the legal regime of the data they collect still persists. In fact, since in several cases we are dealing with the control of vital body functions, if the software of these devices is considered the property of the manufacturing company, then the issue shifts to an even deeper level: companies, based on their own dispositions, intentions, and refusals to maintain, discontinue, or upgrade the relevant software packages, acquire de facto rights of ownership over the users’ bodies; in extreme cases, even rights of life and death. Under no circumstances, however, should it be considered that this generation of IoB devices concerns only therapeutic or preventive medical applications. For example, smart contact lenses that can directly project information or even entire virtual worlds into the eye touch upon the realm of entertainment and social interaction; a segment that, over time, might prove to be more significant and profitable than the strictly medical one.

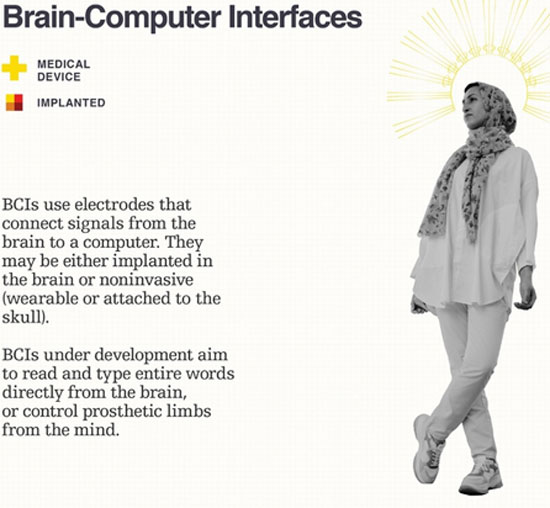

Finally, the third generation, which is considered the least developed for now, includes devices whose goal is to fuse biological and artificial intelligence; in other words, devices that connect to users’ nervous systems and can thus be placed under the direct control of their “minds.” Various types of prosthetic limbs that can move via electrodes connected to the remaining nerves of the amputated limb fall into this category. However, again, it is not at all necessary for the use of such devices to remain strictly within medical—therapeutic contexts. There should be no doubt that the field of cognitive and neural enhancement and optimization will target entire populations, not only patients but also healthy individuals—or rather, primarily healthy ones. For now, existing devices do not appear to provide capabilities for deep diving into neural system structures, generally being limited to what are called “brain-computer interfaces” that function through a tangential connection to the nervous system (e.g., via electrodes). However, exploratory research into the brain’s interior is progressing rapidly9 without anyone being able to say with certainty when their findings will make their way into the real world. If we consider that the coronavirus case and the preventive genetic vaccines presented as salvation against it is a good sample of what follows, then no one should expect thorough safety checks for these devices that aspire to hook onto the nervous system. If the immune system was so easily discarded as obsolete, there is no reason the same won’t happen with the nervous system.

the great collapse

It should be obvious from the above that we are not only facing a paradigm shift in the conception of health and, consequently, of appropriate therapeutic techniques, but also an equally significant restructuring of the conception of the body and, by extension, of the self itself. The body no longer possesses inviolable boundaries, it no longer constitutes an inaccessible fortress the approach to which is permitted only under very specific circumstances and with the utmost reservations, nor is it something which I exclusively possess, according to the beliefs of classical liberalism. The body opens up to the world, becomes almost transparent, from a sphere folded in on itself it becomes an unfolded surface every centimeter of which is available for measurement and examination. There no longer exists any horizon of events, even a vague one, beyond which a hard core of subjectivity is based. A multitude of bodily functions (or even organs) can be replaced by others, artificially enhanced, or even allowed to atrophy to the extent that they are deemed “obsolete.”

Such a development might perhaps be seen as a blessing by some, or even as confirmation of the theories of the so-called extended mind (see the relevant work of the “philosophers of mind” Andy Clark and David Chalmers), according to which what we call “mind” is not limited to the boundaries of the brain or even the body, but includes parts of the external world (e.g., the pages on which I write this article and you read it are part of my and your mind respectively). Such theories start from an initially correct disposition of criticism against conceptions that see the mind as a fundamentally enclosed and fully individualized unit (thus reminiscent of Leibniz’s metaphysical ontology) that only subsequently establishes relations with its environment. To the extent that they suffer from a lack of dialectical sensitivity—and this is a common affliction—they can easily lead to an unrestrained idealism (of the Berkeleyan type). Moreover, the conception of the extended body (to paraphrase the term “extended mind”) that the Internet of Bodies essentially undermines the prior conception that saw the body (and the self) as a completed whole, the result of millions of years of biological evolution. In other words, the body was not treated as a mere cumulative aggregation of individual and independent organs and functions that can be rearranged at will, but as a whole with its own unique teleology under which the individual organs were subsumed—and here one could even invoke Spinoza’s concept of conatus, that is, the effort that every living being makes to maintain its existence as a whole. According to the Internet of Bodies, the Spinozan conatus is nothing but an illusion; the body (can and will) be in continuous communication with its environment, receiving commands from it and constantly ready to respond. It is unknown (at least to our simplistic eyes) what consequences such a “rupture of the vessels” of the human (and perhaps not only) body10 will have. The least one could imagine is seriously disturbed and psycho-intellectually maimed existences in complete identity confusion and unable to synthesize their experiences into a coherent perception of the world and themselves. This in turn is absolutely certain to cause serious disorders in what we call physical health; an organism that cannot clearly distinguish the “outside” from the “inside” is an organism whose immune system will be in permanent crisis and whose nervous system will be in a manic-depressive state: either in hyper-excitement trying to constantly respond to new stimuli and commands, or in catatonia, giving up the demand for continuous action, reaction, and feedback.

The blow against the sense of self and the dissolution of body-based subjectivity will not, however, occur solely through the collapse of the sense of wholeness of individual biological organisms. Given that the ambitions of the Internet of Bodies have a strong flavor of post-humanism, aiming at the hyper-codification of the concept of health towards the “ideal” of continuous upgrading, this implies that any (class-based and not only) distinctions between human subjects may begin to acquire even a biological dimension11. If certain subjects, due to their artificial “enhancements” and upgrades, possess a spectrum of experiences radically different from that of more “outdated” models, without even being able to rid themselves of these augmented experiences due to the deep fusion of the relevant devices with their bodies (except perhaps at great cost), then the fabric of intersubjectivity will begin to be uprooted. What will be the common experiential ground upon which such subjects will be able to stand and establish communication channels? How will they be able to converse and through what vehicle and language? Will “the work of the translator” even be possible when the community of lived experiences has been drained, that secret language of human beings (and living beings in general) that animates individual human languages?12

The issue, of course, is not simply “communicational.” Given that identity and the perception of the self emerge through intersubjectivity, as nodes on the weave of social relations (a solitary being could not even form an identity), any unraveling of this weave would automatically signify an evacuation of individual identities. Such a scenario would certainly be extremely extreme, with very low probabilities of realization. In the most extreme case, we would be talking about the potential creation of even new biological species through such a process of continuous techno-biological differentiation. Even in the mildest scenarios, however, the problem of identity formation remains. Both individual and collective identities are at stake. The 4th industrial revolution seems to envision a universal de-specialization, not only in relation to labor and the knowledge it requires, but even with respect to basic bodily functions, including the very constitution of the self as a unified whole. Never, of course, was the self a secluded, isolated unit, detached from the rest of the world. Yet its subjugation to the norms of all kinds of devices and algorithms is nothing but enslavement.

Beyond the aforementioned, somewhat philosophical and existential, issues, there is another one that is eminently political and economic. It concerns the issue of the cost of social reproduction of subordinate classes in Western societies and the relationship of this cost to the Internet of Bodies. What are the benefits of the Internet of Bodies, according to estimates by the World Economic Forum:13 “enabling remote patient tracking,” “improving patient engagement and promoting a healthy lifestyle,” “advancing preventive care and precision medicine,” and “enhancing workplace safety.” One does not need particularly penetrating insight to realize that the main goal of this entire campaign of body quantification and external dissemination of its information is its strictest control and surveillance, in order to eradicate its bad habits and instill the feeling that it does not belong to you as you thought, that any mistreatment of it constitutes antisocial behavior. Behind the babble about precision medicine, preventive treatments, and continuous care lies a fundamental restructuring of the concept of health, of health service delivery systems, of the related rights that patients can demand, and of the corresponding obligations on the part of the state and private providers. The cost of social reproduction is now deemed “unsustainable”—or, in other words, apparently only contradictorily so regarding the “unsustainable” cost, the sector of social reproduction concerning health can become extremely profitable if relieved of the unnecessary “fat” called “I decide when I am sick, when I will seek treatment, and whether I will follow the advice of this or that doctor.”

It would perhaps not be an exaggeration to say that we are now entering a model of lean social reproduction, by paraphrasing the term lean production (also known as toyotism). Illness, especially non-approved illness, is now seen as waste, as something that must be anticipated and prevented. And whenever this is not possible, it must be eliminated as quickly as possible under the vigilant supervision of the medical gaze14. It would be naive, however, to believe that such a development would bring about at least a general improvement in health. Just as toyotism was not introduced into the productive process in an attempt at de-development, but precisely to increase production, so too will sanitary toyotism likely increase levels of morbidity, being itself in a position to decide what is morbid. The twist: it will not be the morbidity of individual illnesses, but morbidity as a standing condition of social existence, society as a giant intensive care unit where all biological indicators will be recorded. Such a society, permanently at odds with its environment and the nature around it, is already a society morbid at its core. Its only escape will be analgesics, tranquilizers, and self-destruction.

Separatrix

- See related previous articles in Cyborg, many, many, and healthy: health big data is yet another goldmine, vol. 18 – wearable, portable, implantable: your body as motherboard, vol. 10 – precision medicine: the personalization of medicine, vol. 9. ↩︎

- The term is not ours. See the World Economic Forum article, Shaping the Future of the Internet of Bodies: New challenges of technology governance, July 2020, https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_IoB_briefing_paper_2020.pdf ↩︎

- – https://web.archive.org/web/20140121011604

– http://motherboard.vice.com/blog/googles-internet-of-things-now-includes-your-body

– https://www.vice.com/en/article/gvyqgm/the-internet-of-bodies-is-coming-and-you-could-get-hacked ↩︎ - The Internet of Bodies, William & Mary Law Review, 2019. ↩︎

- – https://www.rand.org/about/nextgen/art-plus-data/giorgia-lupi/internet-of-bodies-our-connected-future.html

– https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR3226.html ↩︎ - https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/06/internet-of-bodies-covid19-recovery-governance-health-data ↩︎

- Intelligent Ingestibles: Future of Internet of Body, IEEE Internet Computing, 2020 (https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/9195138), The Internet of Bodies: A Systematic Survey on Propagation Characterization and Channel Modeling, IEEE Internet of Things Journal, 2022 (https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/9490369) ↩︎

- Dick Cheney, the well-known former U.S. vice president, had received such a smart pacemaker. However, after some time it was decided to disable its Wi-Fi connectivity capabilities to the outside world for fear of possible hacking of the device. ↩︎

- A reference to research related to memory was made in the previous issue. See The Machinery of the Spirit, Cyborg, vol. 22. ↩︎

- For the enlightened constructivists, there should be no problem at all. And merely implying that such infinite plasticity can have negative consequences automatically means that one commits the error of “essentialism.” Blessed are the poor in spirit… ↩︎

- For those who find this somewhat excessive, let them consider that it is already happening to a degree: through the separation of vaccinated and unvaccinated individuals. The healthy body has essentially been placed outside the law. This division now clearly takes on class dimensions, with the middle and upper strata of WAPLs (white Anglo-Saxon progressive liberals) being over-represented among the fanatics of vaccination and social compliance measures. See the short article in UnHerd, “To witness the covid divide, walk from Brooklyn to Queens,” https://unherd.com/thepost/to-witness-the-covid-divide-walk-from-brooklyn-to-queens. Fortunately, the woke left is not so easily swept away by the facts of reality and maintains strong resistance. It demands more vaccines for the whole world, even if the rest of the world doesn’t want them. Some other “rebels,” on the other hand, having well assimilated the lesson of union maneuvering, insist that vaccination is a secondary issue (“we are against separations, but whoever doesn’t get vaccinated is an idiot”). And they want the whole “rebel” pie, along with the dog of (intellectual and social) conformity fully fed. ↩︎

- No, we are not constructivists even at the level of language to see it as a system of arbitrary conventions. Those who have not yet overcome such childish ailments, let them see Benjamin’s writings. See Essays on the philosophy of language, W. Benjamin, trans. – ed. – intro. F. Terzakis, Nisos publications. ↩︎

- Shaping the Future of the Internet of Bodies: New challenges of technology governance, WEF, 2020, https://ww3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_IoB_briefing_paper_2020.pdf ↩︎

- It is not a fictional scenario. An insurance company refused to cover the costs for patients with apnea, based on data sent by respirators to its servers, unbeknownst to the patients. Those patients who used the machines for a shorter period than indicated in the instructions lost their compensation. See Health Insurers Are Vacuuming up Details About You – and It Could Raise Your Rates, ProPublica, 2018, https://www.propublica.org/article/health-insurers-are-vacuuming-up-details-about-you-and-it-could-raise-your-rates ↩︎