The following text, apart from being a section of a small tribute to (and against) genetic engineering, has a specific anti-informational significance. It is the official summary of a large (110-page) report commissioned by the “European Council” (the political showcase of the EU) and published last summer (2021). The subject of the report (without being explicitly and bluntly stated) is the circumvention of the ban on “genetically modified organisms” that has been in effect in Europe since 2001, in light of “scientific developments” in biotechnology, the spread of genetic engineering, their “usefulness,” and “international data.”

Neither the content of this “interest,” nor its historical timing is coincidental. Amidst the “health crisis,” and having already authorized the mass use in humans (in the form of “vaccines”) of genetic engineering platforms by bypassing the relevant legislation that prohibited it, the political bosses of the EU, backed by the lobbies of biotech industries, were already preparing the next step: the official and generalized transition to “biotechnologies-for-the-entire-population” (as the Caradinieroi / Pfizeroi would say…).

This official and generalized passage is already on the table. But there are still obstacles. The summary of the report that follows describes the “opportunities” but also the “obstacles” in a technocratic way. It thus offers a good overview of the situation (in European institutions) regarding this extremely critical issue.

Because the subject is among our basic goals of criticism at cyborg since 2014, we will write and rewrite about it. We judge, however, that general and reliable knowledge about what we face – not from a technological but from a “political” perspective, from the bosses’ side – is primarily necessary.

(For Crispr/Cas9 you can refer to earlier issues. Where there is emphasis, it is ours).

translation / rendering

Ziggy Strtdust

On April 29, 2021, the European Commission presented a study on the data of new genomic technologies (NGTs) in accordance with EU law. The Council had requested this study in the context of the European Court of Justice’s 2018 decision and the practical questions it raises.

The Commission’s study examines the application of EU legislation on new genomic technologies, based on consultations with Member States and stakeholders. It provides information on the status and use of NGTs in plants, animals and microorganisms, for agricultural food and for industrial and pharmaceutical applications. The study defines new genomic technologies as “techniques capable of altering the genetic material of an organism, which have emerged or have been developed since 2001”, meaning after the adoption of the existing EU legislation on genetically modified organisms.

The main conclusions of the study highlight “limitations regarding the ability of legislation to keep pace with scientific developments,” stating that this creates challenges in its application and legal uncertainties. According to the study, there is strong evidence that legislation is not suitable for certain new genome technologies and their products, and that it needs to be adapted to scientific and technological advances.

According to the Commission, the study confirms that NGT products have the potential to contribute to sustainable food systems in line with the objectives of the European Green Deal and the “from farm to fork” strategy.

Stakeholders have mixed reactions to the study: while certain industry associations and researchers welcome its content and conclusions, others are more cautious and some environmental NGOs strongly oppose it. In the European Parliament, the Environment and Agriculture Committees (ENVI/AGRI) have organized public hearings and the Parliament’s initial views are being shaped within the framework of the “from farm to fork” strategy.

Introduction

New genomic technologies (NGT) have evolved rapidly over the past 20 years. The 2020 Nobel Prize in Chemistry was awarded to those1 who developed an innovative technique for genome editing, CRISPR-Cas9. This fast, precise, and inexpensive gene-editing technique, described as “genetic scissors,” has revolutionized genome editing since 2012. According to the Nobel Committee, these technologies have led to innovative plant crops, but will also lead to groundbreaking new medical treatments, such as innovative cancer therapies.

The legal regime of these new techniques has raised questions both in the EU and globally. In November 2019, the Council requested the Commission to submit a study in the light of the Court of Justice of the European Union’s (CJEU) etymology in case C-528/16 regarding the regime of new genomic techniques based on EU law. The Commission’s study published on April 29, 2021, covers the use of NGT in plants, animals and microorganisms, and in agricultural, industrial and pharmaceutical applications.

The study concludes that EU legislation on genetically modified organisms faces clear implementation challenges and that legal uncertainties exist regarding new techniques and new applications. The Commission says it will discuss the study’s outcome with the Council, the Parliament, and stakeholders, in order to gather their views on the proposed way forward. What the EU decides to do will also have implications for international trade. Diverging regulatory requirements for NGTs could create technical barriers to trade and, consequently, lead to differences between the EU and its trading partners, within the framework of the ‘farm to fork’ strategy.

The study in a few words

Framework

The EU’s definition of GMOs is contained in Directive 2001/18/EC and reflects the scientific and technical knowledge at the time of its adoption in 2001. Since then, biotechnologies and new techniques, such as the aforementioned CRISPR-Cas technique, have evolved at a rapid pace. This has led to uncertainty as to whether the techniques and products developed through them fall within the definition of GMOs and are therefore subject to the obligations imposed by the directive, such as prior authorization, labeling and traceability rules.

In July 2018, the EU Court issued a decision ruling that organisms obtained through new mutagenesis techniques are GMOs and fall within the scope of EU GMO legislation. The Commission’s study emphasizes that the decision concerns only mutagenesis techniques and not other new genome techniques2.

While the ECJ’s decision focused on new mutagenesis technologies, the Council’s request for the Commission to prepare an explanatory study was broader and referred to NGTs in general. Since there is no definition for NGTs, for the purposes of the study they were defined as technologies capable of altering the genetic material of an organism and which have emerged or have been developed mainly since 2001.

Study methodology; consultations conducted prior to the study

To prepare the study, the Commission conducted a targeted consultation with the competent authorities of the EU-27 and stakeholders at EU level (sectors of the food chain, animal and plant health and pharmaceutical products, cosmetics and the environment). Of the 107 stakeholders invited to participate, 58 responded. The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) provided an overview of risk assessment and the Commission’s Joint Research Centre (JRC) delivered two reports: on scientific and technological developments and on current and future applications of NGTs in the market. In addition, the study took into account the views submitted by the Scientific Advice Group and the European Network of GMO Laboratories, as well as an opinion on the Ethics of Genome Processing by the European Group on Ethics in Science and New Technologies (EGE).

Current status of new genome technologies

The study presents the current state of affairs regarding new genomic technologies, referring to the scientific advisors’ opinion and the JRC reports. The Commission notes that the scientific advisors acknowledged the heterogeneity of NGTs and the fact that this is reflected in the variety of NGT products. Consequently, it may not be ideal to group NGTs into a single category. Furthermore, the scientific advisors highlighted similarities between certain NGTs and certain conventional breeding techniques and established genomic techniques. The advisors concluded that while genome editing can produce “off-target” effects3, the frequency of these effects is generally much lower than in the context of conventional breeding techniques and established genomic techniques4. The scientific advisors also considered that, due to the precision and efficiency of certain NGTs, they constitute the only realistic means of obtaining certain products. According to the scientific advisors, the safety of these products can only be assessed on a case-by-case basis and depends on the characteristics of the products, the use for which they are intended, and the receiving environment. Moreover, it is generally not possible to determine whether changes result from natural causes or the use of any breeding technique.

The JRC overview on scientific and technological developments notes that the development of these techniques is expected to increase across various biological fields. Further improvements of current and next-generation NGTs in the coming years in various organisms will likely expand opportunities for agricultural breeding, industrial biotechnology, and human gene therapies and vaccines. The most significant set of NGTs, according to the JRC, is based on CRISPR-Cas technology, which has exponentially expanded the opportunities for modifying many genomic targets in various organisms.

The JRC review of market applications covers applications in plants, mushrooms, animals, microorganisms and human cells in the fields of agri-food, industry and pharmaceutical biotechnology. The review notes that most NGT applications have been developed in the United States and China. In the EU, Germany has filed the largest number of applications. Due to the flexibility and cost-effectiveness of NGTs (particularly CRISPR), several developing countries are also active in the field. Both private and public/academic entities are actively developing NGT products.

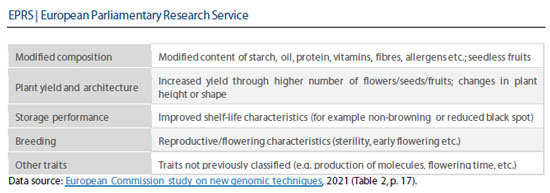

The JRC review identifies two plant applications already on the market: a soybean variety with high oleic acid content featuring a healthier fatty acid profile, and a tomato variety enhanced with gamma-aminobutyric acid. Another 15 plant applications are at the pre-commercial stage5. Some of these are similar to plant/trait combinations already developed using established genetic techniques (e.g. corn, soybean, rice, and potato with herbicide tolerance, fungal resistance, modified oil or starch composition, and non-browning properties), while others have not been previously reported (e.g. herbicide-tolerant peas and flax, cardamom, and cameline with modified oil content). A type of white mushroom that does not brown, created using CRISPR-Cas9, is on the horizon.

In the medium term (by 2030), JRC foresees the creation of plants resistant to drought, alkalinity, and heat, while applications are now in an advanced or early stage of R&D. Improving the nutritional profile of crops (for example, fiber, vitamins), reducing gluten or harmful substances (toxins, allergens, acrylamide precursors), or achieving higher and more stable yields and larger fruit and grain sizes are among the further possible applications.

Regarding animals, the Commission’s study notes that research on NGTs focuses mainly on the animal sector for food production purposes: cattle, pigs, chickens, and various fish species, with desired traits such as resistance to bacteria, viruses, and other pathogens, resistance to high or low temperatures, hypoallergenic properties, higher and faster meat production, or modification of meat quality. The study also mentions gene drive technology, which aims to pass a genetic modification to entire future generations, usually to eliminate pathogen-carrying insects (such as mosquitoes that spread the Zika virus) or to control invasive species.

According to the study, no NGT animal has yet been released into the market, but there are four examples at the pre-commercial stage: tilapia (cultivated freshwater fish) with improved performance/fast growth, disease-resistant pigs, hornless cattle, and heat-resistant cattle. The study points out that a specific use of NGTs in animals is “research and development” work on human diseases: that is, the use of animals as disease models for gene therapy studies or for transplants. For example, mice are used in human gene therapy studies for cancer and genetic diseases, and pigs for creating organs that do not cause transplant rejection in humans.

The study states that in industrial biotechnology, NGT microorganisms already appear to be a reality. Facilitated by the limited use of microorganisms6, the industrial biotechnology sector “rapidly applies technological innovation and NGTs are used alone or in combination with established genetic techniques to improve specific strains.” More commonly, CRISPR is used to eliminate undesirable genes that affect toxins, antibiotic resistance, or unwanted byproducts. Examples of applications include food enzymes (for baking, plant-based proteins, dairy products), probiotics for animal and human health, and bio-control alternatives to pesticides.

Regarding human health, the study observes that NGTs are widely used for the development of pharmaceutical products for human use. NGT applications were identified in 64 clinical trials and there is “extensive activity” in early-stage R&D. Cancer was found to be the main target of therapeutic NGT applications, followed by genetic diseases and viral diseases. The largest group of pharmaceutical products under development is based on genetic modification of T-cells, followed by stem cells and cancer cells.

The study concludes that in the short term, approximately 30 applications in plants, animals and microorganisms are in pre-commercial stage and could reach the market in the next five years. In the medium term, over 100 plants, several dozen animals and medical applications that are now in advanced R&D stage could reach the market by 2030.

The legal framework of organisms developed through new genome technologies

The study reminds that EU legislation on GMOs has two main objectives: i) to protect human and animal health and the environment in accordance with the precautionary principle, ii) and to ensure the effective functioning of the internal market. Therefore, there are strict procedures for safety assessment, risk assessment and authorization for genetically modified organisms before they are placed on the market. In order for consumers as well as professionals (farmers, food chain operators, etc.) to make informed choices, labeling and traceability must be ensured.

EU legislation applies to GMOs as defined in Article 2 paragraph 2 of Directive 2001/18/EC on the deliberate release of GMOs into the environment: “genetically modified organism (GMO)” means “an organism, with the exception of humans, whose genetic material has been altered in a way that does not occur naturally through mating and/or natural recombination.” The definition of GMOs is further refined by a list of genetic modification techniques (set out in Part 1 of Annex IA of the directive), excluding certain techniques (listed in Part 2 of Annex IA) that are not considered to result in genetic modification. Moreover, the directive excludes genetically modified organisms that result from certain techniques/methods (mutagenesis and cell fusion), based on the fact that these techniques/methods have a long history of safe use.

In its July 2018 decision in Case C-528/16 (Confédération paysanne and Others), the Court of Justice of the EU ruled that “Article 3 paragraph 1 of Directive 2001/18/EC, in combination with point 1 of Annex IB of that directive and in the light of recital 17, must be interpreted to mean that only organisms obtained through mutagenesis techniques/methods that have conventionally been used in many applications and have a long history of safety are excluded from the scope of that directive (paragraph 54).” According to the Commission’s study, this decision clarifies that organisms obtained through new mutagenesis techniques that have emerged or have been developed mainly after the issuance of Directive 2001/18/EC are GMOs subject to the provisions of that directive7.

For the purposes of its study, the Commission also examined legislation on GMOs and new genomic technologies in 31 countries outside the EU, concluding that approximately two-thirds do not have specific legislation for NGTs and/or their products, as these are regulated in the same way as conventional GMOs. However, half of these countries are discussing whether they will adapt their legislation specifically to NGTs.

Detectability of new genome technologies

The EU Reference Laboratory (EURL) and the European Network of GMO Laboratories (ENGL) have prepared a report regarding the difficulties of detecting NGT products. The report considers it would be very difficult for laboratories to detect the presence of non-approved genome-edited plant products entering the EU market without prior notification of altered DNA sequences. According to the report, the selection methods based on polymerase chain reaction (PCR) commonly used for detecting conventional GMOs cannot be applied to genome-edited plant products, nor can they be developed for such a purpose. This is because they target common sequences that are generally present in transgenic organisms, which do not appear in plants that have undergone genome editing. DNA sequencing may be able to detect specific alterations of the DNA in a product, but this would not necessarily confirm genome editing, as the same change could have been achieved through conventional breeding or traditional random mutagenesis techniques.

Security assessment of new genome technologies

The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) provided an overview of the risk assessment of plants developed using NGT, based on its previous scientific opinions and those of the competent authorities of the Member States8 from 2012 onwards. The Commission did not ask EFSA to develop new opinions on plants developed through specific NGT.

For NGT applications in plants, EFSA concluded that there are no new risks specifically associated with targeted mutagenesis9 and cisgenesis10 compared to conventional breeding. EFSA also concluded that the unintended effects of modification through targeted mutagenesis are of the same type and fewer than the unintended effects that occur with conventional non-GM breeding techniques. The Commission notes that the types of modifications introduced through targeted mutagenesis and cisgenesis can also occur naturally in the environment without human intervention. No safety assessment has yet been made beyond plant applications.

The Commission states that some Member States expressed concern regarding the likelihood of unintended, off-target effects on the genome of the edited organism and their potential negative consequences for human, animal and plant health, as well as for the environment. The main safety concern expressed was the risk of unintended effects associated with the intended genetic modification: for example, the production of new toxins or allergens. The study recalls that EFSA has noted that random changes in the genome occur independently of the breeding methodology: insertions, deletions or rearrangements of genetic material also arise in conventional breeding and possible new proteins are randomly created also during conventional breeding.

Some stakeholders also emphasized possible negative environmental consequences, such as the introduction of new traits, interactions with wild species, impact on food chains and plant-pollinator interactions; and the potential uncontrolled spread into the environment. Most NGOs, as the Commission emphasized, are particularly concerned about NGT animals and their welfare: some mentioned the potential cancer risk in animals. Others emphasized that animal experiments often cause unnecessary pain and death of animals and that genetically modified animals often have health problems at birth. Concerns were also expressed about genetically modified organisms, particularly regarding their impact on the environment, ecosystems and biodiversity conservation.

According to the Commission, many member states consider that the current risk assessment procedures and guidelines need to be adapted for NGTs. Most NGOs and organic food business operators state that NGT products require risk assessment based on existing GMO legislation or that they require stricter risk assessment, while other stakeholders believe that risk assessment requirements should be decided on a case-by-case basis.

Research activities

The study confirms that there is significant interest in research on new genomic technologies in the EU, but development is taking place mainly outside the EU. The EU, as well as member states and stakeholders, are increasingly funding research related to NGTs: EU funding under the FP7 (2007-2014) and Horizon 2020 (2014-2020) research programs amounted to 3.2 billion euros, distributed across 1,021 projects. Health and medical-oriented research represented the largest portion of the funding. The remainder was bioeconomy research, which includes agri-food applications.

Many member states reported that the current regulatory framework presents challenges for NGT research, placing EU academics and public and private research institutions at a competitive disadvantage internationally. Furthermore, there is a risk of NGT research shifting to locations outside the EU. Many member states highlighted the need for developing reliable detection and traceability methods.

Challenges and concerns regarding new genome technologies

The study points out that some stakeholders are not enthusiastic about the opportunities offered by NGTs. They do not believe that NGTs will bring particular benefits to the agri-food sector: any benefits, in their view, can also be achieved through other forms of agriculture. They also argue that the benefits of NGTs are largely hypothetical and that so far there is no evidence of their ability to contribute to the sustainability of the agri-food system. Finally, they point out that there is insufficient knowledge about the impacts of NGTs on health, the environment, the economy, and society.

The Commission states that the most common concerns of Member States relate to the negative public perception of NGTs in the agri-food sector; difficulties with the effective detection, identification and traceability of NGT products; safety issues; and potential negative environmental impacts. Diverging legal requirements of the EU’s trading partners also cause concern: this could lead to the entry of non-approved products into the EU, and EU farmers and businesses to face unfair competitive conditions. Several Member States also express concern about the ethical aspects of using NGTs.

Many stakeholders consider NGT products to be a significant threat to the sustainability of organic and genetically modified-free species, due to difficulties with controls and certification, the potentially unavoidable presence of NGT products in their supply chains, and the possible loss of consumer confidence.

Those interested in the pharmaceutical sector are concerned about the application of GMO legislation to medicines: since GMO legislation has not been specifically designed for medicines, it hinders the conduct of clinical trials, delaying patients’ access to them and affecting the EU’s competitiveness as a place where advanced therapy medicinal products are developed.

Labeling of new genome technology products

Several stakeholders note that the lack of reliable methods for detecting or differentiating NGT product labeling creates not only a challenge and a legally uncertain situation for operators but also problems in dealing with imports from countries that regulate NGTs differently or not at all. Others emphasize that NGT labeling is crucial for organic and GMO-free farmers and value chains, and that consumers have a right to information according to EU food and Treaty legislation.

Other issues in the Commission’s study

This update provides an overview of the study’s content and issues likely to arise during the upcoming public discussion on what steps should be taken. Among the topics examined in the study but not detailed here (due to their technical complexity) are different types of new genomic techniques and characteristics of genetic modifications (Section 4.1.2 of the study), the application of EU GMO legislation to organisms developed through different technologies (Sections 4.2.2 to 4.2.5 and Chapter 4.3 of the study), and intellectual property rights and patents (Chapter 4.8 of the study). The study also provides a brief overview of the principles guiding the regulation of NGTs in non-EU countries (Section 4.2.6).

The study also summarizes a March 2021 opinion from the European Group on Ethics regarding genome editing. Regarding NGTs in factories, the opinion recommends that regulation should be proportionate to the risk. Milder regulations should be used when the change in the plant could have been achieved naturally or where genetic material has been introduced from sexually compatible plants. Where genes have been introduced from sexually incompatible organisms or multiple changes have been made, there should be a comprehensive risk assessment. The views of Member States and stakeholders on the ethical aspects are further presented in Chapter 4.11 of the study.

Main findings of the study

The Commission concludes that there are challenges regarding the ability of EU legislation to keep pace with scientific developments. According to the Commission, there is strong evidence that the current legislation on GMOs is not suitable for certain NGTs and their products and that it needs to be adapted to scientific and technological progress.

The Commission says that it will soon launch a policy action specifically focusing on plants derived from targeted mutagenesis and cisgenesis. An impact assessment, including public consultation, will be conducted to examine possible policy options. Regarding other NGTs and their use in animals and microorganisms, the Commission says it will “continue to gather scientific knowledge.”

The study also notes that, in general, the use of NGTs in the pharmaceutical sector is viewed more positively than in other sectors: NGTs can be used to develop therapies for serious, debilitating, and life-threatening diseases, as well as for vaccines and treatments to control zoonoses. The Commission clarifies that the use of NGTs in pharmaceutical products will be examined within the framework of the pharmaceutical strategy11.

The Commission also concludes that NGT products have the potential to contribute to sustainable agrifood systems in line with the objectives of the European Green Deal12 and the “from farm to fork” strategy. Both aim to improve the sustainability of the food system, while also highlighting the challenges of climate change and noting that biotechnology can play a role, for example, in reducing dependence on pesticides, in developing crops that are more resilient to climatic conditions, as well as in contributing to food security and a more sustainable food chain.

However, the study points out that NGT safety is the key, and that as both new techniques and new NGT products vary significantly, drawing generalized conclusions regarding their safety is impossible. Case-by-case assessment, the study supports, is widely recognized as the most appropriate approach. Furthermore, as EFSA concluded, similar products with similar risk profiles can be produced either through conventional breeding or through certain genome editing techniques and cisgenesis: meaning that applying different regulatory oversight to similar products with similar risk levels may not be justified.

Regarding the legal framework of NGTs, the study points out that, while the EU Court’s decision has provided significant elements of legal clarity, open questions remain: for example, developments in biotechnology, combined with the lack of definitions (or clarity regarding the meaning) of key terms in the legislation, create ambiguities in interpreting certain concepts, potentially leading to regulatory uncertainty. As examples of definitional gaps, the study refers to basic concepts such as “mutagenesis” (whether EU legislation covers all mutagenesis techniques or only conventional ones); “long history of safe use”; and “altered” genetic material.

The interested parties, as the study notes, are divided on whether the current legislation should be maintained and its application strengthened, or whether the legislation should be adapted to scientific and technological progress and the risk level of NGT products.

European Parliament and Council

Parliament

On 10 May 2021, the Committee on the Environment, Public Health and Food Safety (ENVI) held a public hearing where experts from academic, European and other institutions as well as consumer organisations discussed the potential risks and impacts of NGTs. When presenting the study at the event, the Commission noted that there is strong evidence indicating that the current regulation on genetically modified organisms is not suitable for certain new genomic techniques. It then explained that current risk assessments are too rigid and that “the application of different levels of regulatory oversight to similar products with a similar level of risk may not be justified.” At the same time, new techniques should not undermine other aspects of sustainable food production, such as organic farming13. The Commission also recalled that new techniques can help develop vaccines and treat diseases, and confirmed that it will initiate policy action for plants derived from targeted mutagenesis and cisgenesis. The study was also presented at the meeting of the Committee on Agriculture and Rural Development (AGRI) on 22 June 2021. In December 2015, during the previous Parliament’s term, AGRI had already organised a hearing on new techniques for plant breeding and, together with ENVI, a hearing in May 2018. In its resolutions of January 2020 and June 202114, Parliament called for a global moratorium on the release of gene drive organisms into the environment, including field trials.

The Parliament outlined its initial views on NGTs in its resolution on the ‘farm to fork’ strategy, within the framework of the joint procedure between AGRI and ENVI. A joint committee meeting for voting on the draft report of the initiative took place in September 2021, and the vote in plenary was held in October 2021. Regarding NGTs, the adopted compromise amendment states that Parliament notes the Commission’s plans to initiate a regulatory policy action on plants derived from certain new genomic techniques, aiming to maintain a high level of protection of human and animal health and the environment, while potentially benefiting from science and innovation, particularly to contribute to the sustainability goals of the European Green Deal. Parliament “stresses the precautionary principle and the need to ensure transparency and freedom of choice for farmers, processors, and consumers, and stresses that this policy action should include risk assessments and a comprehensive review and evaluation of traceability and labelling options in order to achieve appropriate regulatory oversight and to provide consumers with relevant information, including on products from third countries, in order to ensure fair competition conditions”.

Council

The Council of Georgia and Agriculture held a discussion regarding the conclusions of the study at its meeting on May 26-27, 2021. The ministers responded positively to the study and assessed the need to modernize the current legislation, while recognizing the particular challenges such modernization presents. They discussed the significance of incorporating recent scientific developments when conducting risk assessments for new genetic techniques, as well as the need for awareness-raising and providing education on these issues.

Stakeholder Reactions

EuropaBio, the European association for the biotechnology industry, considers the NGT study a positive step. The association notes that the current legislation on GMOs does not reflect technological progress and has affected Europe’s global competitiveness. “New genomic techniques are significantly innovative tools in the field of biotechnology and can offer innovative solutions for a healthy planet,” says EuropaBio. Euroseeds, which represents European plant breeders, supports in its statement that the Commission’s study confirms the urgent need for policy change: “urgent action is required from the Commission and member states to allow a differentiated approach to products derived from innovative plant breeding methods.”

In May 2021, more than 20 trade groups for agricultural food products called on EU agriculture ministers to support the study’s findings. They insisted that “a differentiated regulatory approach is needed,” saying it is important to address the issue from a global perspective, also taking into account trade-related challenges. Although they warmly welcomed the prospect of policy action in the plant sector, they also encouraged the Commission to initiate discussions on revising the regulatory approach in other areas. “These techniques have great potential for the livestock sector and for developing new/further evolution and improvement of existing microbial strains to support the transition to more sustainable food systems,” the groups stated.

With a different perspective, in March 2021, the IFOAM group of organic farmers, in alliance with 162 civil society organizations, farmers, and business organizations, sent a letter to Frans Timmermans, Vice-President of the Commission, urging him to ensure that all new genetic engineering techniques continue to be regulated according to the existing EU GMO standards. “There are no scientific or legal reasons for excluding new genomic techniques from risk assessment, traceability, and labeling,” the alliance asserts, warning that weakening the regulation of these powerful techniques would undermine the goals of the EU’s Green Deal, “from farm to fork,” and biodiversity strategies. According to the alliance, the new genetic modification techniques can cause a series of unintended genetic modifications that may result in the production of new toxins or allergens, the transfer of antibiotic resistance genes, or characteristics that could raise concerns regarding food safety, the environment, or animal welfare.

Environmental groups insist on the need for strict application of existing regulations for GMOs in new techniques. The organization Friends of the Earth Europe supports in its briefing from December 2020 that these new forms of genetic modification, although presented as a magical solution, will not make the agricultural system more resilient to extreme weather conditions nor lead to healthier food. “So far, neither the new nor the old generation of GMO technologies have managed to produce crops with significant health benefits,” observes the NGO. Moreover, many studies have shown that gene editing can have unintended “off-target” effects. Additionally, because cellular DNA repair mechanisms play a significant role in the process and involve a certain degree of randomness, it is impossible to reliably predict the exact outcome, even for targeted genes. Friends of the Earth also reminds that biotech companies are legally required to provide a testing method for any GMO approved in the EU, so that unauthorized imported GMOs can be detected.

Environmental supporters also highlight issues regarding the patenting of plants and plant genetic material, warning that patenting a plant or the characteristics of a plant restricts farmers from sowing, planting, harvesting, or reproducing the variety without permission. This threatens farmers’ rights to store, use, and sell seeds from their own harvest and increases their dependence on a few large seed producers.

In a press release from April 2021, the environmental monitoring organization Test Biotech emphasizes that general exemptions from the mandatory approval process cannot be justified, as there are no scientific criteria that allow certain categories of new gene editing applications to be declared safe. “The safety of specific organisms can only be concluded after a case-by-case risk assessment – but not a priori or taking into account only the intended characteristics of genetically modified organisms,” says Test Biotech. The organization also refers to an EFSA opinion from February 2021 on the evaluation of existing guidance lines for conducting risk assessments of plants obtained through synthetic biology. The EFSA opinion evaluates, among other things, the risk assessment of a low-gluten wheat produced through CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing. Test Biotech supports that the EFSA opinion shows that detailed risk assessment must be carried out even if no additional genes have been introduced. According to Test Biotech, EFSA correctly concludes that complex patterns of genetic change exceed what has been achieved so far in genetic engineering and conventional breeding.

The European Network of Scientists for Social and Environmental Responsibility (ENSSER) warns in its press release that the relative ease of use and low cost of CRISPR components, the most well-known and widely used genome editing tool, significantly increase the likelihood of dual use, misuse, and accidental harmful use. It also criticizes the claim that this technology would be crucial in combating hunger by increasing food crop yields, pointing out that the deeper causes of hunger are related to social and economic problems (poverty, conflicts, and exclusion) and not yields. The precautionary principle requires that genome editing remain strictly regulated, says ENSSER, especially since there is no history of safe use for any of these new techniques.

Some academics point out that a key element of the discussion has been and remains the phrase that is part of the definition of GMOs in Directive 2001/18, “altered in a way that does not occur naturally through mating and/or natural recombination.” The main debate concerns whether this refers to the technique used, the genetic modifications that result, or both. Academics emphasize that in its 2018 ruling, the EU Court of Justice addressed only the scope of the mutagenesis exemption. Therefore, the challenge remains to determine the precise scope of the GMO definition itself, say academics, arguing that according to the existing definition, requirements concerning both the process (the genomic techniques used) and the product (the genetic modification that has been made) must cumulatively be met.

Researchers also warn about the economic and environmental consequences of the choices the EU will make, pointing out that, given that in some cases it is impossible to distinguish plants that have undergone genome editing, EU importers may fear that they would risk violating EU legislation. They may choose not to import products based on crops for which genome-edited varieties are available. Consequently, plant products that the EU is currently a net importer of (such as soybeans) will become more expensive in the EU. Intense substitution of products that are covered or not covered by genome editing will occur in consumption, production, and trade, researchers say, resulting in dramatic impacts on the prices of agricultural products and food, as well as on farm income.

Some academics have expressed the hope that the coronavirus pandemic could change the game in GMO regulation—given the contribution of modern biotechnology to the development of a vaccine against the disease—as well as regarding the capacity to address food shortages caused by pandemics or other threats of similar magnitude.

Developments in other international organizations

The OECD organized a conference on the applications of genetic engineering in agriculture in June 2018. A genetic engineering hub was established by the OECD as a result of the work of the OECD Working Group on Biotechnology, Nanotechnology and Converging Technologies. The OECD Working Group on Harmonizing Regulatory Oversight in Biotechnology aims to help countries assess the potential risks from genetically modified organisms.

The Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety to the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) is an international agreement that aims to ensure the safe handling and use of living modified organisms (LMOs) arising from modern biotechnology. International discussions within the framework of the Nagoya Protocol include, among others, the regulatory regime of genome editing techniques. A peer review process for the CBD Technical Series on Synthetic Biology continued from May to July 2021. A revised draft will be made available for the 15th meeting of the Conference of the Parties (COP15), to be held in October 2021 and April-May 2022.

Since the beginning of 2021, WHO has developed a Global Framework for the Responsible Use of Life Sciences, aiming to update guidance in light of advances in the life sciences since 2010. The goal is to promote the responsible use of the life sciences and protect against potential risks arising from accidents and misuse. In May 2021, WHO issued new guidance on research involving genetically modified mosquitoes for combating malaria and other vector-borne diseases. In July 2021, WHO published global recommendations for human genome editing.

In November 2018, the United States expressed concerns to the WTO’s Committee on Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures regarding the European Court of Justice’s decision on organisms obtained through mutagenesis. The United States stated that applying this decision “would create unjustified barriers to trade in genome-edited products and would stifle the agricultural research and innovation necessary to prevent hunger and undernourishment in the coming decades, while ensuring the environmental sustainability of agricultural activities.” Delegations from 10 countries15 also signed a statement regarding the agricultural applications of precision biotechnology, supporting that varieties derived from genome editing should be regulated similarly to conventional varieties due to the significant similarity between the two. The statement warns that different regulatory approaches for products derived from precision biotechnology may create potential trade issues that could hinder innovation.

Opinion

On September 24, 2021, the Commission published its roadmap for legislation on plants produced by certain new genomic techniques, stating that the regulation it intends to propose will concern a legal framework for plants derived from targeted mutagenesis and cisgenesis and for their food and feed products. Comments could be submitted until October 22, 2021, and the Commission should approve its proposal in the second quarter of 2023. On November 29, 2021, the Commission organizes a high-level event on NGTs to discuss the continuation of the NGT study. Gene-edited crops in the EU currently occur only in trial plots, for example in Belgium, Spain and Sweden. The United Kingdom recently approved the first field trials for CRISPR-Cas created wheat, where the aim is to reduce levels of the carcinogenic acrylamide in cereal products. On September 29, 2021, the United Kingdom government published plans to facilitate research and testing requirements for gene-edited crops in England16. The next step, according to the press release, will be the revision of regulatory definitions, “to exclude organisms produced by gene editing.” There were already indications that the United Kingdom wishes to deviate from EU legislation on this issue after Brexit: in January 2021, the United Kingdom launched a public consultation on gene editing. According to the press release of Environment Secretary George Eustice, the potential of gene editing “has been blocked by a decision of the European Court of Justice in 2018, which is erroneous and stifles scientific progress. Now that we have left the EU, we are free to make coherent policy decisions based on science and evidence.”

- The French microbiologist Emmanuelle Charpentier and the American biochemist Jennifer A. Doudna. ↩︎

- For a detailed description of the legislation see ‘Annex E – EU regulation on GMOs’ in the Commission’s study. ↩︎

- “Off-target mutations” are DNA mutations that occur at unintended positions in the genome (see Annex A – ‘Glossary of scientific terminology’ in the Commission’s study). ↩︎

- With the term “established genome techniques” the Commission refers to genome intervention techniques that had been developed before 2001, when the legislation on genetically modified organisms (GMOs) was adopted. ↩︎

- Applications ready for commercialization in at least one country, which have not yet entered the market. ↩︎

- Limited use of microorganisms as bio-factories, and the fact that the final product is usually not the goal of genetic modification/mutation. ↩︎

- However, the Commission’s study concludes that micro-organisms developed through new modification techniques are genetically modified micro-organisms (GMMs) subject to the provisions of Directive 2009/41/EC on the contained use of genetically modified micro-organisms, if used under containment; and to Directive 2001/18/EC if they are deliberately released or placed on the market. ↩︎

- 16 scientific opinions, originating from 8 Member States (AT, BE, DE, DK, ES, FR, LT and NL). ↩︎

- “Targeted mutagenesis” or “techniques of locally oriented mutagenesis” are terms/umbrella terms used to describe newer mutagenesis techniques that cause mutation/mutations at selected positions/targets in the genome, without the introduction of genetic material. The process usually results in a “knockout” (i.e. disruption of the function) of a gene that is considered responsible for an undesirable outcome. (See Annex A – ‘Glossary of scientific terminology’ in the Commission’s study). ↩︎

- “Cisgenesis” means the introduction of foreign genetic material (e.g. a gene) into a recipient organism from a donor that is sexually compatible (crossable). The foreign genetic material is introduced without modifications or rearrangements. ↩︎

- The Commission adopted a pharmaceutical strategy for Europe in November 2020. ↩︎

- The Commission’s position regarding the European Green Deal is that “the EU must develop innovative ways to protect crops from pests and diseases and take into account the role of new innovative techniques to improve the sustainability of the food system, while ensuring that these techniques are safe”. ↩︎

- The position on the “from farm to fork” strategy is that “new innovative techniques, including biotechnologies and the development of bio-based products, can play a role in increasing sustainability, provided they are safe for consumers and the environment, while simultaneously bringing benefits to society as a whole. They can also accelerate the process of reducing dependence on pesticides.” ↩︎

- Resolution on the COP15 of the Convention on Biological Diversity and resolution on the EU biodiversity strategy for 2030. ↩︎

- Australia, Argentina, Brazil, Canada, Dominican Republic, Guatemala, Honduras, Paraguay, USA and Uruguay. ↩︎

- After the announcement, the governments of Wales and Scotland declared that they do not plan to relax their rules regarding genetically modified crops. ↩︎