According to experts, we have a serious problem that needs to be addressed soon: the volume of data is continuously increasing, to a point where the infrastructures for its mass processing and storage are insufficient. They talk about megabytes with many zeros, which are multiplying. Thus, processors with traditional silicon electronic circuits have reached their limits regarding miniaturization, which provides analogously greater processing power. Hard drives, magnetic tapes, and CDs/DVDs also reach their limits in storage density, while being worn out medium to long-term. And data centers as “farms” for mass storage and processing consume a lot of energy.

Among the various solutions – such as quantum computers, storage in glass, diamonds or other chemical elements – the one that seems to stand out is the use of genetic material which, according to experts, constitutes the “code of life”: DNA. And, since it is a “code”, why not put it to do the job it corresponds to? That is, to store and process data. The advantages are “unmatched”: it performs parallel processing faster than the best supercomputer, stores with such density that the data of data centers fit in a few ml of DNA and consumes minimal to zero energy.

The applications for which these new techniques are intended, although they resemble the applications of traditional computers, have a broader scope and often a different field. For example, the use of DNA as a processor for classical computer problems is limited to certain intractable problems that require parallel computations. It is more focused on processing and computations within biological systems, where electronic circuits cannot reach – or if they do, they won’t do such a good job. Similarly, the use of DNA as a data storage medium, while taking the path – and now commercially – of utilizing synthetic DNA produced in laboratories and stored in vials, is also intended and tested simultaneously for the use of genetic material in living organisms.

Although so far the applications of DNA computers in living organisms are still at the laboratory testing level, we cannot be certain how quickly they can evolve. However, on one hand the speed of “technological progress” and on the other the recent example of the mass imposition of experimental genetic engineering technologies under the pretext of emergency need, has made us even more suspicious of the capabilities and intentions of the bosses. Experts speak of a depth of 10 or 20 years before they become practically applicable. And if many things – or even exaggerated things – are heard, perhaps it helps to remember the situation 20 years ago, when the Internet was just a few static websites with crude graphics and not Metaverse; when genetic engineering as medicine was a “distant dream” of biotechnologists and not “vaccines” of salvation.

In the case of synthetic DNA as a “hard disk”, the situation is quite different, as it has already entered commercial application and is expected to “explode” in the very near future. According to market forecasts1 “the market for DNA storage of digital data is expected to increase from $57.81 million in 2021 to $1,761.49 million by 2028. It is estimated that it will grow at an annual growth rate of 61.29% during the period 2021-2028. DNA products for digital data storage can change biological research and significantly affect human health, food security and environmental sustainability, as they are accurate, relatively cheap, easy to use and extremely powerful”.

The “players” who have entered (and) into this “game” are from start-up companies, companies with a heavier biography, national and international health organizations and military “arms”. The classic recipe, that is, which is necessary for every scientific progress….The link of the above research has a list of these companies and we would recommend you to see their corresponding sites, to get a taste of the developments.

Also, as “primary and secondary sources” of this research are mentioned: the World Health Organization (WHO), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the National Digital Health Service (ANHD) and the National Health Strategy (NHS). So do not worry; for our health’s sake it will be…

We will not delve into the concerns that arise from all this now. For the time being, we will present the views of specialists by copying from articles and publications of mainstream and “reputable” media, creating a collection of texts that indicatively traces the course of this field of genetic engineering over the last two decades.

Wintermute

DNA Computing2

Leonard Adleman asks for forgiveness. In an announcement he publishes to fend off journalists requesting interviews, the computer scientist at the University of Southern California and world-renowned cryptographer who invented the field of DNA computing admits that “DNA computers are unlikely to become autonomous competitors to electronic computers.” He continues, somewhat apologetically: “We simply cannot, at this moment, control molecules with the skill that electrical engineers and physicists control electrons.”

It was in 1994 that Adleman first used DNA, the molecule from which our genes are made, to solve a simple version of the “traveling salesman” problem. In this classic puzzle, the goal is to find the most efficient route through many cities, and given that there are numerous cities, the puzzle can stump even a supercomputer. Adleman showed that the billions of molecules in a drop of DNA contained raw computing power that could—perhaps could—surpass that of silicon. But since then, scientists have faced tough practical and theoretical obstacles. As Adleman and others in the field have realized, there may never be a DNA-based computer that directly competes with today’s silicon-based microelectronics.

But this does not mean they abandoned it. On the contrary. Although computer scientists have not found a clear path from the test tube to the computer, what they found surprises and inspires them. Digital memory in the form of DNA and proteins. Highly efficient processing machines that navigate inside the cell, cutting and pasting molecular data into the material of life. Moreover, nature packages all this molecular equipment in a bacterium not much larger than a transistor. In the eyes of computer scientists, evolution has created the smallest, most efficient computers in the world.

As Adleman now sees it, DNA computing is a field that concerns less about beating silicon and more about the amazing new combinations of biology and computer science that push the boundaries in both fields—sometimes in unexpected directions. Scientists continue to work hard on new ways to exploit DNA’s amazing ability to process numbers for specialized types of applications, such as cryptography. But beyond that, the inherent intelligence embedded in DNA molecules could help build microscopic, highly complex structures; essentially using computer logic not to calculate numbers but to build things.

A glimpse into the future of DNA: The doctor inside the body3

Scientists have developed what they say could be the smallest medical kit in the world: a computer, made from DNA, that can diagnose disease and automatically administer drugs for its treatment.

The computer, so small that a trillion of them would fit in a drop of water, now operates only in a test tube and decades may pass before it is ready for practical use. But it offers an intriguing glimpse into a future where molecular machines operate inside humans, detecting diseases and treating them before any obvious symptoms even appear.

“Finally, we have this vision of a doctor inside the cells,” said Dr. Ehud Shapiro of the Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot, Israel, who led the work published online yesterday by the journal Nature.

The role of DNA is to store and process information, the genetic code. Therefore, it is no surprise that it can be used for other computational tasks, and scientists have actually used it to solve various mathematical problems. But the Israeli scientists said that their own was the first DNA computer that could have medical use.

The computer, a liquid solution of DNA and enzymes, was programmed to detect the type of RNA that would exist if specific genes associated with a disease were active.

In one example, the computer determined that two specific genes were active and two others inactive, and accordingly diagnosed prostate cancer. A piece of DNA, designed to function as a drug by interfering with the action of a different gene, was then automatically released from the end of the DNA computer.

Experts described the work as clever but emphasized that it had been done in a test tube, to which RNA corresponding to the disease genes was added. It is unclear, they said, whether such a computer could function inside cells, where there would be many pieces of DNA, RNA and chemical substances that could interfere.

“I think it’s very elegant – it’s almost like a beautiful mathematical proof,” said Dr. George Church, professor of genetics at Harvard Medical School, “but it doesn’t work yet in human cells.”

The DNA computer of the Weizmann institute encodes both the software and the data with the four letters of the genetic code, A, C, G and T. The hardware, the part of the computer that does not change, is an enzyme that cuts the DNA helix in a specific way.

The computer is constructed from double-stranded DNA, with ends that are single-stranded. These so-called sticky ends can bind to specific other DNA or RNA strands in the solution, according to the usual rules of DNA base pairing. If binding occurs, the enzyme cuts the DNA at a specific distance, exposing new sticky ends. If these ends find something to bind to, the enzyme cuts at another location, and so on. If the chain reaction proceeds in a specific manner, the enzyme eventually cleaves off the piece of DNA that functions as the drug.

Once the DNA encoding the problem is created and placed in the test tube, the computer operates automatically and reaches the answer within a few minutes.

“Basically,” says Dr. Shapiro, “we just throw everything into the solution and see what happens.”

DNA computers put bacteria to work4

It is not a regular, silicon-based electronic machine, but the scientists created a computer from a small piece of DNA, then introduced it into a living bacterial cell and released the microbe to solve a mathematical sorting problem.

“A computer is any system that can read some input and give some readable output,” says Karmella Haynes, a biologist at Davidson College in North Carolina and co-author of a new study published in the Journal of Biological Engineering. Haynes and her team attempted to harness the power of DNA recombination to solve the so-called “burned pancake problem”: a puzzle about how burnt pancakes of different sizes, burned on one side and perfectly fried on the other, can be stacked using the fewest number of flips, so that the largest ones are at the bottom and all have the good side up.

“This work is the first job I have encountered that uses living cells to solve a specific computer science problem,” says Tom Ran, a graduate student in computer scientist Ehud Shapiro’s lab at the Weizmann Institute in Rehovot, Israel.

By demonstrating that DNA functioning as a computer could solve “the burnt pancake problem,” Haynes and her team proved that if their system could be scaled up, it could find answers to complex problems such as the most efficient flight paths between Chicago and Singapore or the optimal way to route telephone calls across the U.S.—puzzles that companies like FedEx and AT&T have been grappling with for years—in a fraction of the time required by conventional computers. Researchers have envisioned using DNA computers for many other applications, such as a way to detect changes in living systems—like cancer within the body or the spread of pollutants in a lake.

“DNA computers may be able to achieve things that electronic computers cannot,” says Len Adleman, a molecular scientist at the University of Southern California. “For example, it’s very difficult to imagine how a silicon-based electronic computer could be inserted into a bacterial cell.”

DNA: The absolute hard drive5

As for storing information, hard drives don’t even come close to DNA. Our genetic code packs billions of gigabytes into just one gram. A mere milligram of the molecule could encode the complete text of every book in the Library of Congress and still have plenty of room to spare. All of this was mostly theoretical—until now. In a new study, researchers stored an entire genetics textbook in less than a picogram of DNA—one trillionth of a gram—a breakthrough that could revolutionize our ability to store data.

Some groups have tried writing data into the genomes of living cells. But this approach has several drawbacks. First, cells die—not a great way to lose your work. Also, they reproduce, introducing new mutations over time that can corrupt the data.

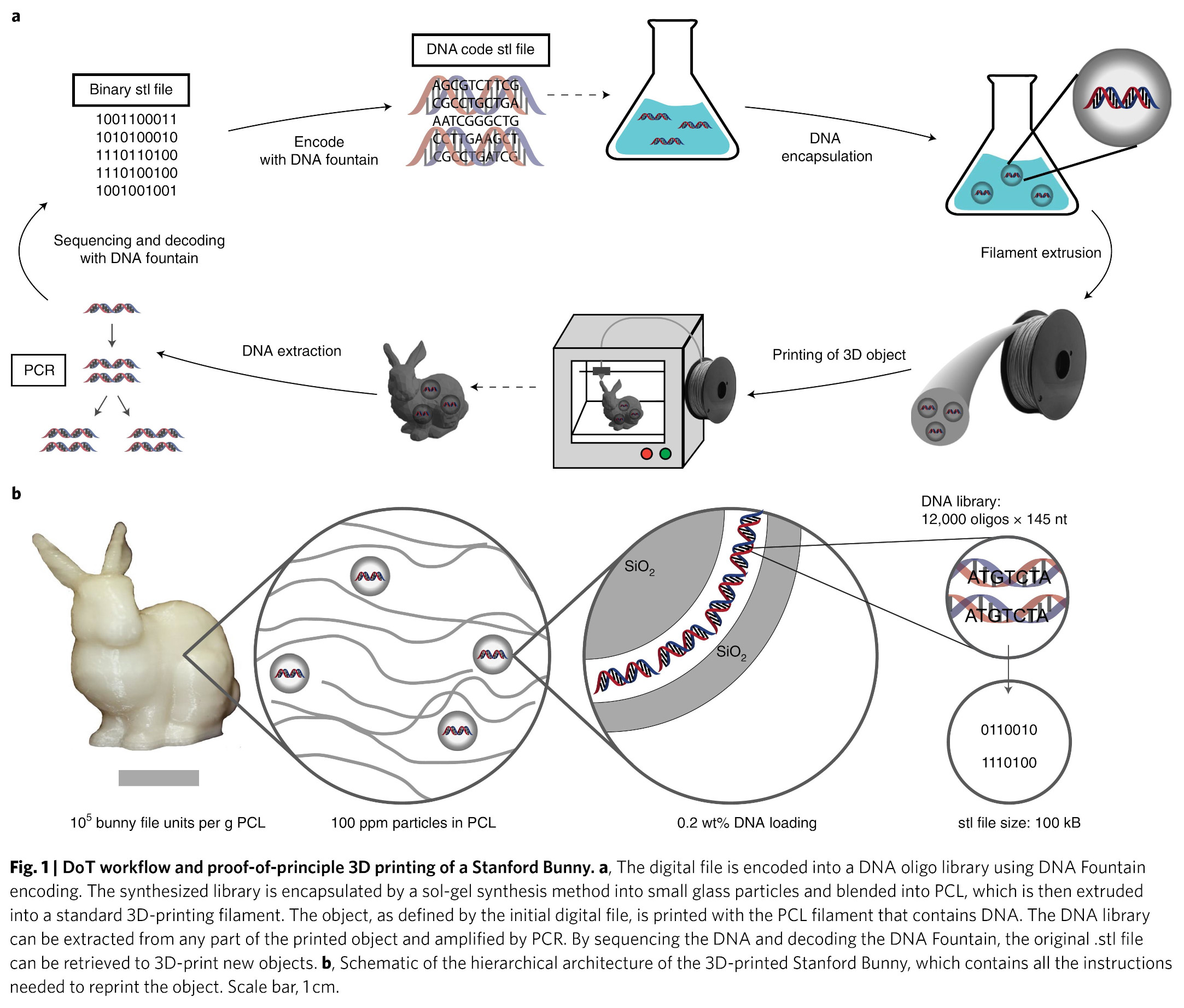

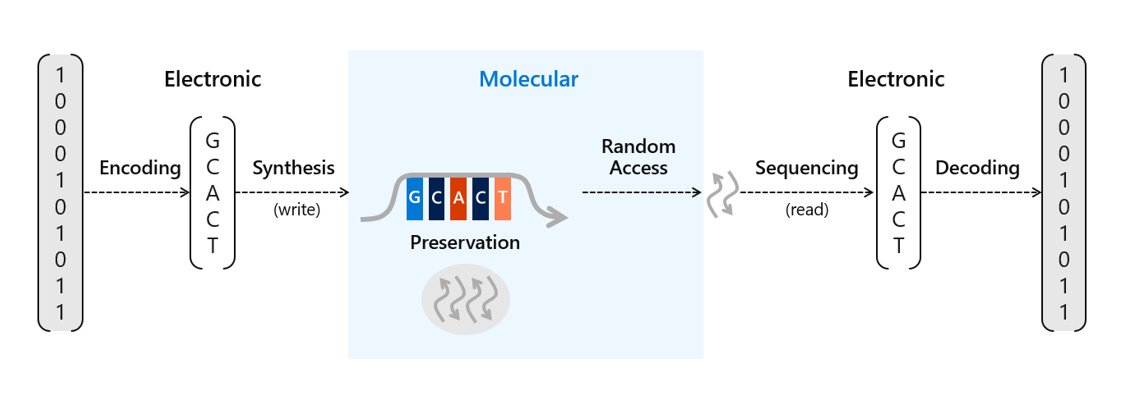

To overcome these problems, a team led by George Church, a synthetic biologist at Harvard Medical School in Boston, created a DNA information archiving system that doesn’t use any cells at all. Instead, an inkjet printer embeds tiny fragments of chemically synthesized DNA onto the surface of a microscopic glass chip. To encode a digital file, the researchers break it into microscopic data blocks and convert that data—not into the 1s and 0s of standard digital storage media, but into the alphabet of DNA’s four letters: A, C, G, and T. Each DNA piece also contains a digital barcode that records its location in the original file. Reading the data requires a DNA sequencer and a computer to reassemble all the pieces in order and convert them back into digital form. The computer also corrects errors. Each data block is reproduced thousands of times, so that it can be detected and corrected by comparing it with the other copies.

To demonstrate their system in action, the team used DNA chips to encode a genetics book that Church had written. It worked. After converting the book to DNA and translating it back to digital form, the team’s system had a record-low error rate of just two errors per million bits, equivalent to a few typographical errors in a letter. This is on par with DVDs and much better than magnetic hard drives. And because of their microscopic size, DNA chips are now the storage medium with the highest known information density, the researchers report online today in Science.

However, don’t replace your hard drive with genetic material just yet. The cost of the DNA sequencer and other equipment “makes it currently impractical for general use…”, says Daniel Gibson, a synthetic biologist at the J. Craig Venter Institute in Rockville, Maryland, “…but the field is moving fast and the technology will soon be cheaper, faster and smaller”.

What can DNA computers do?6

For more than 20 years, researchers have been exploring how DNA could be used as a material for computers. It sounds very promising due to the incredible data density in DNA: it stores all the information and instructions needed to build and operate a human body. Some researchers have managed to encode large texts into DNA. Others have used the molecule to create simple logic gates and circuits, the basic building blocks of computers. But using DNA in this way is unjustifiably slow for the kinds of tasks we expect computers to perform. Most likely, DNA computing will be utilized to function within living cells and combine with their existing mechanisms, enabling new methods for detecting and treating diseases.

Traditional computers use a series of logic gates that convert different inputs into predictable outputs. For example, a transistor is turned on or off by a high or low voltage input. With DNA, the way molecules can be activated to bind to each other can be used to create a circuit of logic gates in test tubes. In one method, called DNA strand displacement, the DNA input that binds to a DNA logic gate displaces a DNA strand that serves as the output. Multiple gates can be combined into a circuit: each DNA output will bind to the next logic gate until a predictable terminal output strand is released. (Scientists can make the terminal strand fluoresce so that it can be easily read.)

In another method, the DNA input can bind to a DNA logic gate and activate naturally occurring enzymes, such as polymerases and nucleases, to cut DNA strands. These can then bind to other strands in a continuous series of reactions or display a fluorescent output signal.

Researchers in Israel showed last year that DNA logic gates can also function inside living organisms—specifically in cockroaches. The researchers created DNA folded like origami to make what they called nanoscale robots. The nanorobots act as the input helix in the computational sequence: they connect with DNA logic gates, a process that changes the shape of the robots so that they expose their useful payload. The payload can be a molecule such as a short DNA sequence, an antibody, or an enzyme. If the payload can activate or deactivate a second robot, this will create a circuit inside a living cell.

Other researchers have also shown, in early work, how DNA computers can be used for extremely accurate cancer detection. They would do this by creating a specific output if a cell expresses too much of a particular gene or has specific microRNA sequences.

DNA-based computing requires something like a new programming language. In the initial experiments, models of the reactions occurring with a given set of components were used. Microsoft subsequently developed a language called “DNA Strand Displacement Tool,” which can be used to design the DNA sequences required to execute circuits and to model how reactions will occur in each circuit.

DNA computing technology is unlikely to replace conventional silicon computers. However, within five to ten years, DNA-based computers could be controlled for medical applications.

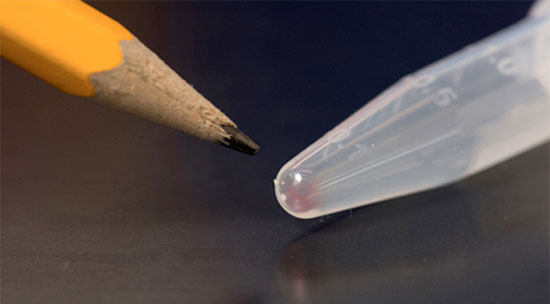

Big leap from Microsoft7

It looks like a test tube with dried salt at the bottom, but Microsoft says it could be the future of data storage. The company said today that it had written about 200 megabytes of data, including “War and Peace” and 99 other classic literary works, into DNA. Researchers have proven that digital data can be stored in DNA in the past, but Microsoft says no one has written so much data into DNA at once.

«The company is interested in learning whether we can create a system that stores information, is automated and can be used for commercial use, based on DNA», says Karin Strauss, Microsoft’s lead researcher on the project, which also includes researchers from the University of Washington.

IDC predicts that the total amount of stored digital data worldwide will reach 16 trillion gigabytes next year, most of which will be housed in massive data centers. Strauss estimates that a shoebox-sized DNA storage device could hold the equivalent of approximately 100 data centers.

Reinhard Heckel, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of California, Berkeley, who has worked on DNA data storage, calls this “impressive.” But he says the biggest obstacle to making DNA data storage useful is cost, because creating custom DNA molecules is expensive. “For people to actually use it, it needs to become cheaper than magnetic tape, and that will be difficult.”

Microsoft does not disclose details about how much it spent to create the 200-megabyte DNA data storage, which required approximately 1.5 billion bases. But Twist Bioscience, which synthesized the DNA, typically charges 10 cents per base. Commercially available DNA synthesis can cost as little as 0.04 cents per base. Reading one million DNA bases costs about 1 cent.

H Strauss is convinced that the cost of DNA sequencing and writing will decrease significantly in the coming years. She says there are already indications that it is decreasing faster than the cost of manufacturing transistors over the past 50 years, a trend that has been the driving force behind many innovations in computers. It cost about $10 million to sequence a human genome in 2007, but close to $1,000 in 2015.

“You can become your medical history”8

Instead of a continuously increasing number of massive data centers, each consuming large amounts of energy, it’s nice to imagine a small number of diamond or DNA data centers. It is literally possible that each of us could someday carry our own data center with us.

It seems very likely that, in the foreseeable future, you will be able to sequence your DNA in near real-time, analyze it for defects/mutations, and have treatments specifically tailored to your results – possibly even edit your genes/DNA. This, after all, is the goal of “personalized medicine” (Precision Medicine).

What would make it even cooler is that, as we read your DNA, your entire medical history is also being read – perhaps from the cloud, but perhaps also from synthetic DNA that you will have implanted, or even from your own DNA, if we start writing directly into it. And of course, these DNA files will also be updated in near real-time.

This and if it is possession of your own data!

DNA computers against viruses9

Don’t take it the wrong way, but you are simply data. Your genes built you, from the tips of your feet to the top of your head. In this sense, you are no different from a computer: The code produces the output that is your body.

In fact, over the past two decades, scientists have used actual DNA as if it were literal code, a process called DNA computing, to do things like calculate square roots. Today, researchers report in the journal Nature Communications that they have developed DNA that detects antibodies – the soldiers your body produces to fight viruses and related threats – by executing a sequence of molecular instructions. Someday, the same computations could automatically release drugs in response to infections.

[…]Certainly, you can do blood tests for antibodies. This is the old-fashioned way. The idea here is to use DNA computing as a permanent control device for antibodies one day. You could use this setup to create DNA nanocapsules that would deliver drugs. “The DNA produced by our DNA computer can be used to unlock this nanocapsule,” says Maarten Merkx (a biochemist at the Eindhoven University of Technology in the Netherlands and the main author of the new research). His team specifically examined viruses such as the flu and HIV, so perhaps the “package” could carry more antiviral antibodies.

The study also represents a leap in the way DNA computing generally works. “It certainly offers another tool in the toolkit for those who want to design complex computational strategies,” says Philip Santangelo, a biomedical engineer at Georgia Tech who was not involved in the research. “You could use proteins and enzymes to create computer architectures that use many biomolecules, not just DNA.” More complexity means greater accuracy and quality in the types of programs scientists can run.

Sure, you might just be data. But in the right hands, this data could one day work wonders for medicine.

DARPA “explores opportunities”10

As the complexity and volume of global digital data increases, so does the need for more capable and compact data processing and storage media. To address this challenge, DARPA announced the Molecular Informatics program, which seeks a new paradigm for data storage, retrieval, and processing. Instead of relying on the binary digital logic of computers based on Von Neumann architecture, Molecular Informatics aims to explore and exploit the broad spectrum of structural characteristics and properties of molecules for encoding and manipulating data.

“Chemistry offers a rich set of properties that we may be able to exploit for fast, scalable information storage and processing,” said Anne Fischer, program manager at DARPA’s Defense Sciences Office. “Millions of molecules exist, and each molecule has a unique three-dimensional atomic structure as well as variables such as shape, size, or even color. This wealth provides a vast design space for exploring innovative and multiple ways of encoding and processing data beyond the 0s and 1s of today’s digital architectures.”

CRISPR “takes cells to the movies”11

Researchers are developing ways to use DNA, the blueprint of biological life, as a synthetic raw material for storing large amounts of digital information outside living cells, using expensive machinery. But what if they could force living cells, such as large populations of bacteria, to use their own genome as a biological hard drive that can be used to record information and then retrieve it at any time? Such an approach could not only open up entirely new data storage possibilities, but also build upon an efficient memory device that can chronologically record the molecular experiences cells undergo during development or exposure to stress and pathogens.

In 2016, a team from the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering and Harvard Medical School (HMS), led by George Church, a member of the Wyss Core Faculty, built the first molecular recorder based on the CRISPR system, which allows cells to acquire DNA information in chronological order, creating a memory of it in the bacterial genome as a cellular model. The information, stored as a series of sequences in CRISPR, can be retrieved and used to reconstruct a timeline of events. However, “as promising as this was, we didn’t know what would happen when we tried to track about a hundred sequences simultaneously or if it would ultimately work. This was critical, since we aim to use this system to record complex biological events,” said Seth Shipman, a postdoctoral fellow working with Church.

Now, in a new study published in Nature, the same team demonstrates in fundamental proof-of-concept experiments that the CRISPR system, developed further as a first-of-its-kind approach, is capable of encoding information as complex as a digitized image of a human hand and one of the first motion pictures ever made, that of a galloping horse, into living cells.

“In this study, we show that two CRISPR system proteins, Cas1 and Cas2, which we have converted into a molecular recording tool, together with a new understanding of sequence requirements for optimal spacers, allow a significantly increased ability to acquire ‘memories’ and deposit them in the genome – as information that can be provided externally by researchers or that in the future could be created by the ‘natural experiences’ of cells,” said Church, who is also a professor of genetics at Harvard Medical School and Professor of Health Sciences and Technology at Harvard and MIT. “When further exploited, this approach could present a way to prompt different types of living cells in their natural environments to record the formative changes they undergo, in a synthetically created memory space in their genome.”

[…]In future work, the team will focus on installing molecular recording devices in other types of cells and further engineering the system so that it can memorize biological information. “One day, perhaps we could track all the developmental decisions a differentiating neuron makes, from the early blastocyst stage to that of an extremely specialized cell type in the brain. This would lead us to a better understanding of how fundamental biological and developmental processes are ‘choreographed’,” said Shipman, who, in addition to Church, also has as advisor the neurobiologist and co-author Jeffrey Macklis, Professor of Life Sciences and Professor of Stem Cell and Regenerative Biology at Harvard University. Once adapted to specific examples, this approach could also lead to better methods for creating cells for regenerative therapy, disease modeling, and drug testing.

“This cutting-edge technology advances the field of DNA-based information storage by leveraging the biological mechanism of living cells to record, archive, and propagate this information, while also providing a new way to study the dynamics of biological and developmental processes within the living body. It is yet another example of bio-inspired engineering at its finest,” declared Donald Ingber, Founding Director of the Wyss Institute, who is also the Judah Folkman Professor of Vascular Biology at HMS and the Vascular Biology Program at Boston Children’s Hospital, as well as Professor of Bioengineering at SEAS.

Can we encode medical records in our DNA?12

In 1878, a series of photographs of a rider on his galloping horse was transformed into the first motion picture titled “The Galloping Horse.” Recently, researchers at Harvard University were able to recreate this classic moving image in the DNA of E. coli bacteria. Correct. They encoded a film into bacteria.

Images and other information have already been encoded into bacteria for years. However, Harvard researchers took it a step further with the CRISPR-Cas gene editing tool. This process allows cells to collect information encoded from DNA, in chronological order, so that they can create a memory or an image, just like a movie camera does. […] Their work changes the way complex systems in biology can be studied. Researchers hope that over time, these recorders will become the standard in all experimental biology.

[…]Jeff Nivala, a researcher in the genetics department at Harvard Medical School, believes that researchers can now look for new ways to use the technology, such as programming gut bacteria to record information about your diet or health. “Your doctor could use this data to diagnose and monitor a disease,” Nivala said.

While Nivala believes that microscopic cameras that will “surf” through our body and brain will become a reality in the future, he says this may be a bit far off. Especially given that building machines at the molecular scale is a challenge. “Realistically, we are probably far from being able to record every cell in the brain’s synaptic activity,” he said. “The CRISPR-Cas system is prokaryotic, which means there are certain challenges that must be overcome when transferring these genes to mammalian cells, particularly when we don’t exactly know how every part of the CRISPR-Cas system works in bacteria.”

However, he believes that when this happens, it will be due to the convergence of biology and technology. “How small can we make a digital recording device using conventional materials such as metal, plastic, and silicon? The answer is that we are not even close to achieving the accuracy and precision with which biology can construct nanoscale devices,” Nivala said. But we shouldn’t feel bad about that, he added. “Nature had only a few billion years’ head start. That’s why engineers are now turning to biology for new ways to build things at the molecular scale. And when you build technology from biology, it’s much easier to interface and connect with natural biological systems,” Nivala said. He is confident that this current work lays the foundation for a cell-based biological recording system that can be combined with sensors, allowing the system to detect any relevant biomolecule.

Could all this lead to encoding information in our DNA, such as our medical records or Social Security number or our credit card details?

To some extent, this is already happening at the vending machine company Three Square Market in Wisconsin. About 50 of the company’s employees accepted their employer’s offer to implant an electromagnetic microchip in their hands. They can use it to buy food at work, log into their computers, and operate the printer. It is the size of a grain of rice and is similar to chips implanted in pets for identification and tracking purposes. However, this chip has an operating distance of only 6 inches. BioHax International, the Swedish manufacturer of the chip, wants to eventually use the chip for broader commercial applications.

This is just the beginning of the possibilities, according to Nivala, who believes that one day our most important data will be stored in our cellular DNA. “In a way, some of it already is. Our genome is very important. But imagine if we could store all our family medical history, photos and family videos in reproductive sequence cells, which could then be passed on to our children within their genome,” said Nivala. “You might even be able to store your mother’s amazing lasagna recipe. I bet future generations would be very grateful for that.”

DARPA wants to create a DNA image search engine13

Most people use Google’s image search feature either to investigate potential copyright infringement or for shopping. Did you see some shoes you like on Instagram? A subsequent search will then display all matching images, including websites that will sell you the same pair. To make this possible, Google’s computer vision algorithms had to be trained to extract recognition features such as colors, textures, and shapes from a vast catalog of images. Luis Ceze, a computer scientist at the University of Washington (UW), wants to encode this same process directly into DNA, making the molecules themselves perform this computer vision function. And he wants to do it using your photos.

On Wednesday, Ceze’s team at UW launched a social media campaign to collect 10,000 images from around the world and store their pixels in A, T, C, and G, which are the building blocks of life. They have done something similar in the past. In 2016, they encoded an entire music video, setting the record for the largest amount of data stored in DNA. But this time, they decided to collect the data by creating a site where anyone can upload their photos and encouraging users to share their images on social media with the hashtag #MemoriesInDNA. “DNA can last thousands of years,” says Ceze. “So this is essentially a time capsule. What would you like to preserve forever?”

The #MemoriesInDNA campaign by UW might be a small trick—there are many available, high-quality image databases that can be used to train a molecular search engine. But the science behind it is a real effort to overturn the last six decades of computing. DNA-based storage so far has only been good for this: encoding pixels and “locking” them into DNA helices invisible to the human eye. Until now, no one has figured out how to retrieve and process data stored in DNA—a necessary first step to creating any kind of serious molecular computing platform.

Who would want this though? Well then, DARPA certainly would.

Over the past few months, the service of the Department of Defense that has taken on the task of funding some of science’s most ambitious hopes has begun investing millions in discovering radical, non-binary ways of working with data. “Molecules offer a very different approach to ‘computing’ compared to the 0s and 1s of our existing digital systems,” says Anne Fischer, program manager for the Molecular Informatics program at Darpa, which so far has allocated $15.3 million to corresponding projects at Harvard, Brown, the University of Illinois, and the University of Washington. “The global community is generating data at an enormous rate, and developing new approaches to access and process this information is crucial for addressing emerging shortages in storage capacity and computational speed.”

The digital age began with a simple act of delegation: man assigns memory to the machine. First in vacuum tubes, then in transistors and magnetic disks. After more than 60 years, the basic architecture based on the logic described by John von Neumann continues to underlie modern computer infrastructures. And by all measures, it has served humanity well. However, its limitations are becoming apparent as people create increasingly complex data.

“Moore’s Law has to do with the miniaturization of devices,” says Karin Strauss, senior scientist at Microsoft and collaborator on the University of Washington project. “Electronics are great and will continue to exist naturally, but molecules are the final frontier when it comes to miniaturization.” Chemistry offers an untapped palette of molecular diversity – properties such as structure, size, charge, and polarity – that could be exploited for information processing.

DNA is not the only molecule that interests DARPA. Brenda Rubenstein is a theoretical chemist at Brown, where she worked on quantum computing—encoding pieces of information either as atoms, ions, photons, or electrons. But now she is extending this idea to organic compounds, especially those that have multiple sites for R-groups (R-groups: the variable parts of molecules that give them different physical and chemical properties) to attach. Performing different reactions modifies these R-groups in predictable ways, making them good for computing basic linear algebra equations, says Rubenstein. “They have so many properties, there is an incredible capacity for storing and processing information,” she says. “I think small molecules are almost an obvious choice for expanding the field of computing.”

DNA: The datacenter of nature14

IARPA is seeking molecular information storage technologies (MIST) that can retain vast amounts of data in a small footprint for long periods without degradation and that are advanced enough in the research process to be commercially viable within 10 years. DNA could meet all these requirements, according to an announcement from the agency that was released this week.

The storage of molecular information has been a theoretical idea for decades, but it has recently reached some significant milestones. In 2016, researchers at the University of Washington and Microsoft Research were able to encode four digital images into DNA and then successfully retrieve them without data loss. If these molecular storage methods are perfected, they could offer information storage densities 10 million times greater than current technologies. They could also preserve data intact for hundreds of years, significantly reducing operational and maintenance costs, according to IARPA.

IARPA met with interested parties in 2016 and 2017, but now wants to make the technology a reality, therefore it plans to develop the MIST program. “The fundamental goal of the MIST program is to develop storage technologies that can ultimately be scaled to the exabyte regime and beyond, with reduced physical footprint, power, and cost requirements compared to conventional storage technologies,” the solicitation states.

The service is seeking solutions from a number of fields – including chemistry, molecular biology and microfluidics – that could feed into MIST. Its goal is to be able to store and retrieve data from a MIST storage solution and to have an operating system that helps facilitate the process. The MIST program, which will consist of two two-year phases, is expected to launch later this year with a two-day workshop in the Washington area.

DNA-based reprogrammable computer15

DNA is supposed to save us from the morass of computers. With advances using silicon weakening, DNA-based computers promise massive parallel computer architectures that are impossible today.

But there is a problem: The molecular circuits that have been built so far have no flexibility at all. Today, using DNA for computations is “like needing to build a new computer from new hardware, just to run new software,” says computer scientist David Doty. So, Doty, a professor at UC Davis, and his colleagues began to explore what would be needed to implement a DNA computer that is actually reprogrammable.

As described in detail in a paper published this week in Nature, Doty and his colleagues from Caltech and Maynooth University proved exactly this. They showed that it is possible to use a simple “trigger” to “convince” the same basic set of DNA molecules to apply many different algorithms. Although this research is still exploratory, reprogrammable molecular algorithms could be used in the future to program DNA robots, which have already been successfully used to deliver drugs to cancer cells.

[…]This experiment was “basic science” in its purest form, a proof of concept that produced beautiful, albeit useless, results. However, according to Petr Sulc, an assistant professor at the Biodesign Institute of Arizona State University who was not involved in the research, the development of reprogrammable molecular algorithms for nanoscale assembly opens the door to a wide range of potential applications. Sulc suggested that this technique could one day be useful for creating nanoscale factories that would assemble molecules or molecular robots for drug delivery. He said it could also contribute to the development of nanophotonic materials that could pave the way for computers based on light rather than electrons.

“With these types of molecular algorithms, one day we may be able to assemble any complex object at the nanoscale level, using a general programmable set of “building blocks,” just as living cells can come together into a bone cell or a neuron cell simply by selecting which proteins are expressed,” says Sulc.

IARPA invests in DNA data storage16

The Intelligence Advanced Research Projects Activity awarded a total of $48 million to two groups seeking to develop digital data storage using synthetic DNA.

The Molecular Encoding Consortium, led by Robert Nicol of the Broad Institute, announced on Wednesday a $23 million award from IARPA’s Molecular Information Storage Program (MIST). The consortium also includes Donhee Ham’s research group at Harvard University and DNA Script, a French synthetic DNA startup. In a statement, the consortium members said they planned to collaborate with Illumina to decode data stored in DNA using next-generation sequencing analysis.

IARPA also awarded $25 million to the Georgia Tech Research Institute for the Scalable Molecular Archival Software and Hardware (SMASH) project. Twist Bioscience announced on Wednesday that it will synthesize DNA for the SMASH project as a subcontractor. SMASH will also include teams from the University of Washington (UW), Microsoft, and Roswell Biotechnologies.

IARPA launched the MIST program in 2018 with the goal of developing data storage technologies that will scale to 1 billion gigabytes or more in capacity, with reduced physical footprint and energy consumption. The program, which IARPA expects to last four years, will investigate technologies in three technical areas: storage, retrieval, and operating systems.

As part of the SMASH award, $5.5 million is designated for a new CMOS chip project that will enable DNA recording using the efficiency of current semiconductor technology. Georgia Tech will conduct this research, but Twist said it will commercially apply the project. Researchers from UW and Microsoft will contribute to the system’s architecture, data analysis, and expertise in software development. Roswell Biotechnologies will also provide a chip and a high-performance DNA data reading platform.

How to store all data in DNA17

[…] Besides cost, the other major problem with using DNA for data storage is the difficulty of selecting the file we want from all the others. «If we assume that DNA writing technologies reach a point where it’s economically efficient to write an exabyte or zettabyte of data to DNA, then what? We’ll have a pile of DNA, countless files, images, movies and other things, among which we’ll have to find that one photograph or movie we’re looking for», says Bathe. «It’s like trying to find a needle in a haystack».Currently, DNA files are conventionally retrieved using PCR (polymerase chain reaction). Each DNA data file includes a sequence linked to a specific PCR identifier. To find a particular file, this identifier is added to the sample so that the desired sequence can be found and amplified. However, a disadvantage of this approach is that there can be interaction between the identifier and other DNA sequences off-target, resulting in different files being “retrieved” from the desired ones. Also, the PCR retrieval process requires enzymes and ends up consuming most of the DNA that existed in the pool. “We burn the haystack to find the needle, because all the remaining DNA is not used and essentially thrown away,” says Bathe.

As an alternative approach, the MIT team developed a new retrieval technique involving encapsulating each DNA file into a small silicon particle. Each capsule carries a label with single-stranded DNA “barcodes” that correspond to the contents of the file. To demonstrate this approach in a cost-effective manner, the researchers encoded 20 different images into DNA pieces of about 3,000 nucleotides, equivalent to approximately 100 bytes. (They also showed that the capsules could accommodate DNA files up to one gigabyte in size.)

Each file carried barcodes corresponding to labels such as “cat” or “airplane.” When researchers want to retrieve a specific image, they take a sample of the DNA and add identifiers that match the labels they are searching for — for example, “cat,” “orange,” and “wild” for an image of a tiger, or “cat,” “orange,” and “domestic” for a house cat. The identifiers are labeled with fluorescent or magnetic particles, making it easy to remove and detect any matches from the sample. This allows the removal of the desired file while leaving the rest of the DNA intact for storage again. This retrieval process allows the use of Boolean logic statements, such as “president AND 18th century” resulting in George Washington, similar to that found in Google image searches.

[…] George Church, professor of genetics at Harvard Medical School, describes the technique as “a giant leap forward for knowledge management and search technology.” “The rapid progress in writing, copying, reading, and storing low-energy archival data in DNA form has outpaced the minimally explored opportunities for accurate file retrieval from massive databases,” says Church, who was not involved in the study. “The new study dramatically addresses this problem by using a completely independent external DNA layer and leveraging different properties of DNA—hybridization instead of sequencing—and furthermore, using existing instruments and chemicals.”MIT biological engineering professor Mark Bathe envisions that this type of DNA encapsulation could be useful for storing “cold” data, meaning data that is archived in a database and not accessed very frequently. His lab is creating a startup, Cache DNA, which is now developing technology for long-term DNA storage, both for storing DNA data long-term and for clinical and other existing DNA samples short-term. “Although it may be some time before DNA becomes a viable data storage medium, there is already a pressing need today for low-cost bulk storage solutions for existing DNA and RNA samples from Covid-19 tests, human genome sequencing, and other areas of genomics,” says Bathe.

(The research was funded by the Naval Research Office, the National Science Foundation, and the Office of Naval Research of the USA.)

The first data recorder in DNA18

CATALOG, based in Boston, is the leader in DNA-based digital data storage and has just secured $35 million in funding to proceed with the development of a computational platform where both data management and computing are carried out through synthetic DNA. DNA computer systems based on chemistry offer air-gap protection, are immune to traditional electronic security vulnerabilities, have a low physical footprint, and consume little—or in some cases zero—energy for data storage and handling.

The proprietary data encoding scheme of CATALOG and the new approach to automation aims to unlock the means for integrating DNA into algorithms and applications with potential widespread commercial use. Expected application areas include artificial intelligence, machine learning, data analysis, and security. Additionally, initial use cases are expected to include fraud detection in financial services, image processing for defect discovery in industry, and digital signal processing in the energy sector.

“The simple storage of data in DNA is not our end goal,” stated Hyunjun Park, founding member and CEO of CATALOG. “CATALOG will fundamentally change the data economy by enabling businesses to securely analyze and create business value from data that would have otherwise been discarded or archived in cold storage. The possibility of an extremely scalable, low-energy, and potentially portable DNA-based computing platform is within our capabilities.”

CATALOG’s first DNA writer, Shannon, was named in honor of the father of information theory, Claude Shannon. It is capable of performing hundreds of thousands of chemical reactions per second. Currently, it only provides storage, but future versions of the automated DNA-based data platform will introduce computational capabilities. This will be the first commercially viable and automated platform for DNA storage and computing, for enterprise use.

The Yottabyte Era19

A kilobyte is 1000 bytes and a zettabyte is 1000⁷ bytes. Between kilobyte and zettabyte, with powers of 1000, there are megabyte, gigabyte, terabyte, petabyte and exabyte. After zettabytes come yottabytes. In 2016, Cisco announced that we are in the Zettabyte era, with global Internet traffic reaching 1.2 zettabytes. We will be in the Yottabyte era before the decade ends.

People have been working on DNA storage for many years. I first wrote about it in 2016, when I speculated that it might mean we could literally be our own medical record. We’re not yet at the stage of practical storage in DNA and probably won’t be for many more years, but it’s hard to believe we won’t get there eventually. Unlike any other form of storage we have, DNA can last almost indefinitely and as long as there are intelligent species based on DNA, they will want to read it. Most importantly, DNA can store vast amounts of data. As MIT professor Mark Bathe said: “All the data in the world could fit in the coffee cup you drink in the morning, if it were stored in DNA.”

What prompted me to write about this now was an announcement from Microsoft. In collaboration with researchers from the Molecular Information Laboratory at the University of Washington, their work presented a “proof of concept” for a molecular controller that allowed them to write to DNA up to “three orders of magnitude” – that is, 1000 times – more densely. As the announcement stated: “Ultimately, we were able to use the system to encode a message into four helices of synthetic DNA, and this is a proof that DNA recording at the nanoscale is possible in dimensions necessary for practical DNA data storage.”

The publication concludes: “…we predict that the technology will scale further to billions of features per square centimeter, allowing the synthesis throughput to reach megabyte-per-second levels in a single recording unit, which will be competitive with the recording throughput of other storage devices. We predict that these ‘assemblers’ will be used in other fields such as materials science, synthetic biology, diagnostics, and molecular biology experimental assays.”

Similarly, the announcement concludes: “We predict that technology will reach arrays containing billions of electrodes capable of storing megabytes of data per second in DNA. This will bring the performance of DNA data storage and cost much closer to magnetic tape.”

So that no one thinks that only Microsoft is working on this, there have been many other promising developments in recent weeks. Interesting Engineering highlighted some of these:

Researchers at the Georgia Tech Research Institute have developed a microchip that allows faster DNA sequencing and expect it to be 100 times faster than current technologies. Lead researcher Nicholas Guise told the BBC that, since DNA can survive so long, “the cost of ownership falls to almost zero.”

Scientists at Northwestern University have demonstrated a new “enzymatic system” that encodes three bits of data per hour. The university’s announcement explains: “Our method is much cheaper for recording information, because the enzyme that synthesizes the DNA can be directly manipulated.” The researchers believe that the technique could be used to install “molecular recorders” inside cells to function as biosensors. The possibilities are amazing.

A team at China’s Southeast University used a new process to split data content into sequences, rather than one large single chain, while “reducing” the tools used. TechRadar speculates that it could lead to the first DNA storage device for the mass market. Professor Liu Hong told Global Times: “Now we aim to combine information electronics and biology, which can be used in various aspects, including data storage and nucleic acid testing for viruses.”

Interesting Engineering may have lost the most interesting use so far: Business Insider India reports that Roddenberry Entertainment created an NFT of Gene Roddenberry’s signature on the first Star Trek contract and stored it in DNA embedded in bacteria – “the first living eco-friendly NFT.” The bacteria are currently dormant, but if revived, they will copy the NFT as they reproduce.

It is possible that DNA storage may never become fast enough or cheap enough to replace existing storage methods. It is possible that some other new technique will emerge that is even better than DNA storage. But we are DNA-based beings, and the ability to use the technique with which nature builds us to store and handle the data we produce is unbeatable.

There are already “robots” based on DNA and computers based on DNA, so honestly, DNA storage does not surprise me at all. We should expect molecular DNA recorders – and try to predict how we would and would not want them to be used.

In the 21st century, biology is informatics and vice versa. DNA is not only our genetic history and future, but information that we can read and write. We call it “synthetic biology” now, but as the field grows, we are likely to forget the “synthetic” part, just as “digital health” may simply become “health” or “cryptocurrency” may simply become “currency”.

Life in the Yottabyte era will be very interesting.

- DNA Digital Data Storage Market Forecast to 2028 – https://www.researchandmarkets.com/reports/5557873 ↩︎

- DNA Computing – DNA-based PCs? Doubtful. But DNA might do some computing-while assembling nanostructures.1/5/2000 – https://www.technologyreview.com/2000/05/01/236306/dna-computing ↩︎

- A Glimpse at the Future of DNA: M.D.’s Inside the Body. 29/4/2004 – https://www.nytimes.com/2004/04/29/us/a-glimpse-at-the-future-of-dna-md-s-inside-the-body.html ↩︎

- DNA Computer Puts Microbes to Work as Number Crunchers. 30/05/2008 – https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/dna-computer-puts-microbe ↩︎

- DNA: The Ultimate Hard Drive – Researchers have stored an entire genetics textbook in less than a picogram of DNA, or one trillionth of a gram. 17/8/2012 – https://www.wired.com/2012/08/dna-data-storage ↩︎

- What Can DNA-Based Computers Do? Biological computing is most promising for novel medical applications. 4/2/2015 – https://www.technologyreview.com/2015/02/04/169455/what-can-dna-based-computers-do ↩︎

- Microsoft Reports a Big Leap Forward for DNA Data Storage. 7/7/2016 – https://www.technologyreview.com/2016/07/07/158934/microsoft-reports-a-big-leap-forward-for-dna-data-storage ↩︎

- You May Become Your Own Medical Record. 3/11/2016 – https://tincture.io/you-may-become-your-own-medical-record-a0a0d7169ef2 ↩︎

- Running DNA Like a Computer Could Help You Fight Viruses One Day. 17/2/2017 – https://www.wired.com/2017/02/running-dna-like-computer-help-fight-viruses-one-day ↩︎

- Turning to Chemistry for New “Computing” Concepts – DARPA explores approaches to store and process vast amounts of data using encoded molecules. 23/2/2017 – https://www.darpa.mil/news-events/2017-03-23 ↩︎

- Taking cells out to the movies with new CRISPR technology – Genome engineering technology transforms living cells into archival data storage devices that capture, store, and propagate information over time. 12/7/2017 – https://wyss.harvard.edu/news/taking-cells-out-to-the-movies-with-new-crispr-technology ↩︎

- Can We Encode Medical Records Into Our DNA? 13/8/2017 – https://www.healthline.com/health-news/can-we-encode-medical-records-into-our-dna#Encoding-personal-information-into-our-DNA ↩︎

- Darpa Wants to Build an Image Search Engine out of DNA. And your photos could end up in its database. 24/1/2018 – https://www.wired.com/story/darpa-wants-to-build-an-image-search-engine-out-of-dna ↩︎

- DNA: Nature’s data center – The Intelligence Advanced Research Projects Activity is looking for a new storage medium that can hold more data within a smaller footprint. Is DNA the answer? 28/2/2018 – https://gcn.com/data-analytics/2018/02/dna-natures-data-center/296110 ↩︎

- Finally! A DNA Computer That Can Actually Be Reprogrammed. DNA computers have to date only been able to run one algorithm, but a new design shows how these machines can be made more flexible – and useful. 21/3/2019 – https://www.wired.com/story/finally-a-dna-computer-that-can-actually-be-reprogrammed ↩︎

- IARPA Commits $48M to DNA Data Storage. 15/1/2020 – https://www.genomeweb.com/informatics/iarpa-commits-48m-dna-data-storage ↩︎

- Could all your digital photos be stored as DNA? – World Economic Forum & MIT. 16/7/2021 – https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2021/06/research-shows-dna-could-be-a-solution-to-the-world-s-data-storage-problem ↩︎

- DNA-based chemical computing could revolutionize the IT industry. 30/9/2021 – https://betanews.com/2021/09/30/dna-based-computing-revolutionize-it ↩︎

- DNA Storage in the Yottabyte Era. Demand for data storage is skyrocketing. 7/12/2021 – https://onezero.medium.com/dna-storage-in-the-yottabyte-era-76c87235ced5 ↩︎