It is presented as one of the ambitious (often monstrous) “solutions to the climate crisis”… But its advocates talk about anything else except the “climate crisis” and how this plan will address it. Logical, yet insidious: the “15-minute cities” plan aims to intensively control the daily lives of those living in them; behind its promotional facade, it is a scheme for digital public order. And (it couldn’t be otherwise…) it is promoted as making use of the experience of health restrictions and house arrests from 2020 onward – repackaged as care for “quality of life”…

What is this about? The “15-minute cities” plan, at this stage, provides for the prohibition of private vehicle traffic within cities, through the creation of digital technology blocks on various streets. Apart from the prohibition, what is presupposed is that the location of each vehicle will be digitally controlled. On the other hand, the plan provides for the “coverage of all basic needs of citizens” at a short distance from their homes; and their movement on foot or by bicycle (except, where needed, by public transport). This short distance is determined at 1 kilometer, perhaps a little more: this is what someone can cover by walking for 15 minutes.

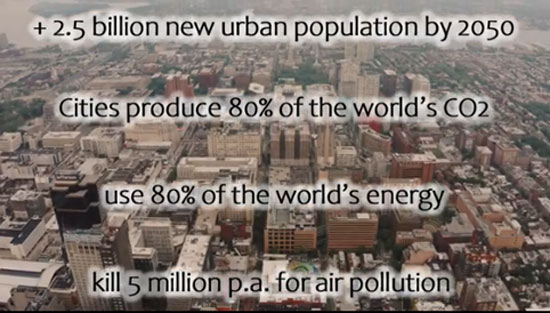

Seen from the perspective of carbon dioxide emissions from internal combustion engines (and this is all there is to “addressing climate change”…), the plan is outright misleading. Electric vehicles are not just around the corner, but already on the market (initially electric vehicles, or EVs), and the trend is clearly in their favor. Consequently, the sins of internal combustion engines are set to disappear within the next decade—not only in cities, but outside them as well. Everywhere. So, what exactly is the contribution of “15-minute cities” to reducing emissions? Essentially, none! Moreover, even the circulation of electric vehicles within cities will be restricted under this plan! Here is the first key observation: the “15-minute city” plan is a fraud when it comes to addressing the “climate crisis”!

What purposes does it serve?

Whether unexpectedly or not, while the “15-minute” initiatives and methodologies of various authorities in western capitalist metropolises cite as their origin an Italian futurist academic, professor of urban planning/design at the Polytechnic of Turin (Luca S. D’Acci), and a French-Colombian also futurist urban planner (Carlos Moreno), the actual design and implementation of this specific spatial planning began by the Chinese state/capital already in 2016. The specifications for the design of urban residential areas (standard for urban residential area planning and design) were incorporated into Chinese national legislation on standards (something like the western ISO) in 2018 as mandatory for both “new cities” and old ones (code GB 50180-2018). Where the real innovation in the implementation of the idea of “15-minute cities” can be found, any interested party can discover, without disorientation and unnecessary fairy tales with climate dragons, the real goals of this plan.

In the December 2016 study titled The Construction of Life Circles in China under the Idea of Collaborative Governance: A Comparative Study of Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou1 the authors introduce the logic of the matter:

The model of social governance in China has entirely different characteristics from Western society due to the unique development and perceptions of a Traditional Eastern Society with a history of several thousand years. However, since the era of reforms and opening-up in 1978, China’s traditional rural society has dissolved and transformed due to the influence of modernization and urbanization, forming a new order of spatial development and various governance models in the mainland country. In recent years, along with the construction of modern high-speed transportation systems and the development of communication technologies, the daily behavior of urban residents, especially those living in metropolitan areas, has followed a trend toward greater diversification.

On one hand, the rapid expansion of urban areas makes the relationship between cities and surrounding regions under the existing governance system particularly complex; the government, as well as city administrators, continues to seek more effective means of managing urban societies. On the other hand, citizens’ behaviors are no longer confined by administrative boundaries, as both the driving force of citizens’ economic capabilities and their strong desire to achieve a higher quality of life lead to a wide range of cross-regional behaviors.These two types of phenomena create new problems for city administrators. The resources of a city are limited in terms of quality and quantity, especially regarding social services. Limited resources do not meet the demands for better quality of life for all citizens, and the constraints of managing inter-regional resources are difficult to operate.

New ideas have emerged from collaborative governance to address such problems… The Life Cycle has emerged as such an idea, aiming to cover the deficiencies of various sectors through their cooperation…. The concept of the Life Cycle is closely related to Behavioral Geography and is extensively used in East Asia, such as in Japan, Korea, and Taiwan… The first focus point is the spatial model of the Life Cycle. Xu introduced the concept of the Life Cycle into the daily lives of residents, and in this sense, the essence of the Life Cycle is sustainability, so that we can create an analytical system composed of the living environment, the ecological environment, culture, leisure, and relationships…

According to Chinese standardization, there are (must be created) 4 scales of urban areas: the 15-minute walking neighborhood; the 10-minute walking neighborhood; the 5-minute neighborhood, and the residential block. The 15-minute neighborhood means “a residential area divided based on the principle that residents can meet their daily living and cultural needs by walking for 15 minutes; the area will be surrounded by expressways or boundaries, with a population of 50,000 to 100,000 people (17,000 to 32,000 households) and complete supporting infrastructure.”

It is clear what problems the detailed zoning model with distance terms (15, 10, 5 minutes) must solve from the Chinese prototype. Firstly, the very rapid urbanization, the concentration in cities not just of thousands but millions of new residents from China’s vast rural interior, creates particularly severe pressure on infrastructure (housing, schools, healthcare, cultural centers, parks, entertainment) and supplies (networks) from the side of the state, regional and municipal administrations. Moreover, however, the dissolution of traditional, rural forms of shaping and controlling behaviors, and their “liberation” in a way within the megalopolises and their anonymity, makes the issue of controlling behaviors in urban conditions central; even more so if these new “anonymous” urban environments happen to exhibit deficiencies (from unemployment to various social infrastructures). In other words, public order problems in megalopolises were not addressed by the Chinese state as a theoretical, possible future issue manageable with more police; but rather as an issue of daily life formation, both from the perspective of basic infrastructure and supplies, and from the perspective of behaviors and the use of these infrastructures and supplies.

We will not dispute that such problems are real and serious for China’s rapidly developing capitalism. It is logical that the regime would not want its megacities to acquire either the French banlieue or the American ghetto. But precisely for this reason, the organization of urban zoning as a “life circle” with a diameter of 1 kilometer or slightly more, and subsequently the conception of a social organization in “life circles” of smaller diameter, reaching down to the residential block, is initially and ultimately an answer to the question of public order, understood in a Chinese social-democratic capitalist way: we (as state, as administration) will properly organize the infrastructure and services in each such “cell,” but you (as citizens, as residents) will be careful, productive, and law-abiding in certain ways, since (or: because) the traditional forms of shaping and controlling your behaviors no longer apply.

The behavioral geography mentioned by the authors of the aforementioned study could be understood as the “sociology of relationships, choices, and behaviors in relation to each particular environment.” From this perspective, the idea of “life cycles” in urban conditions suggests, shapes, theorizes, and normalizes a behavioral urban planning / spatial organization that goes far beyond conventional rules (e.g., traffic or common tranquility), proposing the “middle scale of urban housing” as the pattern of balance and control.

And while the causes of Chinese provocations and “solutions” are clear, what are the causes of the adoption of the “15-minute cities” model by Western states/Western capitalisms?

An unsigned praise on this model from the ohe2 site dated February 26, 2021, insists (not at all convincingly) that the root cause is the “climate crisis,” exposing something of the sort of “cities without vehicles” (indifferent to how they move…), however making the toxic correlation:

… The covid-19 pandemic [we are at the beginning of 2021, at the start of the generalization of platformization, therefore the previous phase with general and undifferentiated restrictions on movement and house arrests is beginning to recede… leaving the field to «travel passports»…] reinforced questions regarding traditional ways of life [sic] with many workers having now gotten used to working remotely and, at times, being required to move within just a few kilometers from their homes due to public health measures. Consequently, can life change the way we think about our neighborhoods and cities and ultimately achieve the goal of the Paris Agreement, which is to keep the increase in average global temperature as close as possible to 1.5 degrees Celsius?

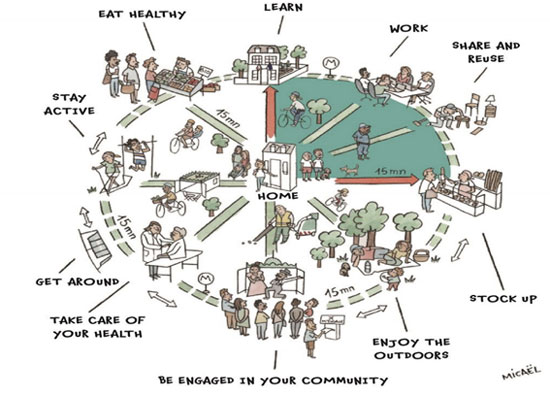

Here is the 15-minute city, a concept developed by professor at the Sorbonne Carlos Moreno. It’s a relatively simple idea: wherever anything we need – jobs, shops, parks, schools – could be within a fifteen-minute walk or bike ride.

This would make the city more decentralized, resulting in less need for cars and the reimagining of public space so that it has fewer roads, more green spaces, bike lanes, sports and recreation infrastructure…

Rather a roughly hewn attempt at idealizing an idea without references to its practical aspects of application, yet with a crucial connection: the urban prohibitions and compulsions of the sanitarian terror campaign.

The ambitious spirit within the cynicism of those it represents (now in decline…) «global economic forum», a year later, on March 15, 2022, under the title «the surprising stickiness of the ’15-minute city’»3 could say (or imply) somewhat more. Our emphasis:

… For traditional urban planners, the 15-minute city simply resembled a new packaging of the historical process of urban development: areas with multiple uses, pedestrian-friendly. As the saying goes, old wine in a new bottle. But in order to create a new framework capable of triggering a global urbanization movement, it is clear that more is at play.

The obvious, albeit not yet complete, answer is the pandemic. Could Paris Mayor Anne Hidalgo have pushed for a progressive urban design without the context of the pandemic? Undoubtedly, yes. But with covid-19 and its variants keeping everyone confined to their homes (or closer to it than usual), the 15-minute city went from being a “nice-to-have” to a rallying cry for convergence. Suddenly, being able to meet all one’s needs within walking or cycling distance became a matter of life and death. The pandemic created an urgent need for equitable urbanization that transcended long-standing community debates about bike lanes and other “amenities.”

When the moment for a new framework arrives, something more than a trend occurs. Before the pandemic, few urban planners would have taken seriously the idea that “home” could become the central organizing factor of all urban planning. Despite predictions about increasing “telecommunications,” working from home remained marginal. Indeed, work and commerce have always been the central organizing factors of urbanization, from the post-agricultural revolution through the industrial and technological ages…

And journalist Lisa Chamberlain continues on behalf of the World Economic Forum under the rather shameless subtitle “the creative destruction of cities”:

COVID-19 can now turn all this upside down, and this explains why the 15-minute city concept is now being reinforced in a way that couldn’t have happened before the pandemic. As shown in the image below, the 15-minute city places the home at the center of urban spatial relationships. The point is not to have every cultural amenity and satisfaction of human desire just outside one’s door. New York can only have one Broadway district. But there is no doubt that Midtown Manhattan should follow a recovery path similar to that taken by Lower Manhattan after the 9/11 terrorist attacks: diversification. And this also applies to the suburbs, which are significantly further along the diversification curve than they were before.

Indeed, the decentralization of work will not kill the city, it will save it. It will take a lot of creative destruction on this journey, but that’s the way the city renews itself: from within. Cities that do not decentralize work will struggle in ways both familiar and unimaginable.

As climate change and global conflicts cause shocks and pressures at a faster rate and with increasing intensity, the 15-minute city can become even more critical… Specifically, communities that promote and maintain social and economic relationships do not need to be wealthy, but they need to be walkable and safe, with residential buildings and commercial centers untouched…. Thus, it will become possible for neighbors to know and understand each other: as local business owners, workers, colleagues, social service providers, educators, and friends. These are the people who come together when such a thing is needed. The mutual aid groups that emerged during the pandemic serve as an example of the importance of social cohesion in a crisis, and this works only when needs are within reasonable distance from where people live…

Very humanistic is this interest of the global social forum in (handcrafted) “social solidarity” (an interest which, without a second thought, means transferring to the plebeians themselves a good portion of the cost of their social reproduction). However, no matter how many times the “amen” of green capitalism (the “climate crisis”) is said, IT IS NOT this the cause of the institutional push (experimental at this stage) for urban enclosures of the “15-minute city” type. And this is not hidden. The cause lies in the easier (for the regimes) “crisis management,” whatever those crises may be. Including… all of them. From wars and semi-wars, to uprisings. The “pandemic” is only (not a small thing!) the allegory of health zones in every sense of the term. We learned (from where else?) from China, during the (paranoid from a health perspective but completely rational from the viewpoint of biological warfare exercises) mass house arrests from mid-2021 onwards: the design and implementation of those exclusions was done, precisely, based on the “15, 10, 5-minute city / residential complex” model. The trials, the organization of care but also of discipline, were conducted through this urban zoning. The assessment of the population’s capabilities, disabilities, and limits was done “in rolling urban slices.”

A movement titled Reconnecting Oxford has already been created (photos below), with an open public campaign as well as sabotage actions against roadblocks…

Even in its Chinese version, the “15-minute city” plan seems to favor permanent and stable residence. More or less those who live in privately owned houses. What consequences could this have for the nomads of cities (renters) or for foreigners (visitors, tourists)? The former, for example, would have to constantly change schools for their children in order to move within each new urban “life cycle”? (No, if “distance education” becomes generalized!…) The latter would be forced to move around the urban concentration of hotels? (No, if “virtual tourism” becomes generalized!…)

Depending on the city, the above are not exceptions! And the question becomes stronger, causing even greater suspicion if we are talking about historical cities, where social infrastructure has been located for decades, and where daily life has been organized for generations around the specific spatial layout. The Chinese logic of covering all basic needs—health, education, entertainment, work, commerce, leisure—within circles of a radius of one or two kilometers cannot be applied to already structured environments. What remains is a brutal demand for discipline, condensed into the “lesson of quarantine”: “non-essential movements” are prohibited (or made significantly difficult)! In short: all movements are controlled.

From this perspective, the “15-minute city” plan has specific dimensions. First, the ideological: the incorporation of mass surveillance, obviously (also) through digital means. Immediately after comes the urban planning aspect. A combination of factors has already caused, since 2020, a “flight trend” from large Western cities (primarily, though not exclusively, in the U.S.), a trend toward relocation to smaller ones. Some theorists of capitalist crises (and of “creative destruction”…) could hope (or even orchestrate) the strengthening of this trend and its exploitation.

What does this mean? It means new cities. There is an old futuristic plan under the general name “technopolises,” which envisioned the construction of entirely new cities “dedicated” to research and applications of new (from the 1970s) technologies: a combination of a “technology park” and an urban unit. Despite the ambitions, very few such “technopolises” were built from scratch globally by the beginning of the 21st century. One of the most well-known is the French Sophia Antipolis, near the Mediterranean border with Italy. With approximately 200,000 residents (significantly larger than a “15-minute city”), Sophia Antipolis hosts 15 specialized universities, technology institutes, and research centers, as well as 2,500 companies (mainly in computing, telecommunications, pharmacology, and biotechnology). Needless to say, it is a “clean / shiny / green” city, a kind of techno-oasis, with all the social and commercial infrastructure and activities one would expect for residents working in “good positions” at such companies and institutions: from schools and playgrounds to churches and bus lines.

This old plan seems to have started being refreshed on a much larger scale, with less emphasis on the campus/park of techno-enterprises, and more on the new kinds of technologically “augmented” housing/daily life. Augmented life… It is not only the Chinese state/capital that, due to mass urbanization, is obliged to build new cities, where the “15-minute” model can be applied from the foundations. It is also many other states/capitals with goals and interests directly aimed at the technological/ digital transformation of life as a whole, towards the “new normalities” (including the reorganization of both work and public order), and of course towards universal control/datafication. The pink cloud for cities of pedestrians and cyclists is also cities “without crime,” cities of social credit. Perhaps also cities “only for renters” (with class-stratified “life cycles…”), that is, cities owned by large companies.

As for car-free cities? They are (we assume with certainty) the plan/dream of sharing corporate-owned flying vehicles for short and medium-distance travel within or outside these cities.

The list of plans for building cities from scratch is literally enormous, on all continents, in dozens of countries. Even if 1/10 of these plans are implemented in the coming decades, it will be a literal “construction orgasm” on the planet, without (necessarily…) having been preceded by the complete destructiveness of an extensive 4th world war.

(Or will it have been preceded?)

Ziggy Stardust

- Accessible in pdf format here ↩︎

- Accessible at https://unfccc.int/blog/the-15-minute-city ↩︎

- Accessible at https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2022/03/15-minute-city-stickiness/ ↩︎