“You are not healthy… you should behave like sick people”.

Greek (and not only) state and experts – 2020

“The new model that is person-centered, behavior-oriented and not disease-oriented – to lead to a sustained behavior change”… “Instead of assuming that individuals are ‘fully rational’, it recognizes that decision-making is influenced by biases, habits and social norms”… “and could result in a 10% to 15% reduction in medical costs, combined with greater productivity gains and better quality of life”

McKinsey (and not only) – 2012

The report we are translating below was published in 2012 by McKinsey, the largest and oldest consulting firm. The term “consulting” is rather mild to describe the work of companies like McKinsey, which have more to do with strategic planning than with “advising those interested.”

This does not imply that they “pull the strings,” but rather that with their “volume” and expertise (unlimited access to information/data and a huge “fleet” of graduates, specialists, executives, etc.), they are able to assess the past and estimate trends—at least in the language of statistics. And thus, subsequently, to “advise” interested parties (companies, organizations, states, and leaders) on the correct path they should follow in order to be among the winners of the next round. In this particular case, the winners will be (they say) those who focus on the patient. Not in order to understand the illness, its causes, and possible treatment. But in order to understand the barriers to changing his behavior1.

Changing patient behavior: the next frontier in healthcare

Changing individual behavior is at the heart of healthcare. The old model of healthcare – a reactive system that treats diseases after they occur – is evolving into a patient-centered model focused on prevention and continuous management of chronic conditions.

This development is necessary. Across the globe, health risks are increasing, driven by population aging and the growing prevalence of chronic diseases. Health systems are innovating in the area of care delivery to respond to this challenge, through increased emphasis on primary care, integrated care models, and performance-based reimbursements.

Nevertheless, much more needs to be done to reorient health systems toward prevention and the long-term management of chronic conditions. In an analysis we conducted on the cost of healthcare in the US (which now approaches $3 trillion annually), 31% of these expenditures could be directly attributed to behaviorally influenced chronic conditions. 69% of the total cost is significantly affected by consumer behaviors. Poor medication adherence alone costs the US more than $100 billion annually in avoidable healthcare expenditures. The burden (on costs) that consumer choices impose in low- and middle-income countries is equally striking: Harvard and the World Economic Forum have estimated that non-communicable diseases result in economic losses for developing economies equivalent to 4% or 5% of their GDP annually. If health systems fail to find ways to make people change their behavior—both in choosing a healthy lifestyle and in seeking and receiving appropriate preventive and primary care for managing their health conditions—they will fail to curb healthcare costs without harming the quality of or access to care.

Designing and implementing programs for sustainable behavior change is difficult. Of the programs tested in the past, only a few had a lasting impact. However, many of these interventions had their roots in the old model of healthcare, focusing on treating clinical problems after the event. Very often, the interventions had poor design, insufficient measurement rigor, and implementation problems. The failures led many healthcare system leaders to be skeptical about whether any behavior change program can have a long-term impact.

We believe that behavior change programs can succeed, but only if we reconsider their design model. This article describes an emerging approach – a person-centered, behavior-oriented model rather than disease-oriented, to lead to sustainable behavior change. Instead of assuming that individuals are “fully rational”, it recognizes that decision-making is influenced by biases, habits, and social norms. Rather than focusing exclusively on the doctor-patient relationship, it seeks to create a “supportive ecosystem” that engages individuals and their closest people.

Our perspectives are based on the analysis of global trends, our extensive experience collaborating with clients across the healthcare industry, and interviews with leading experts. They are grounded in emerging insights from behavioral sciences that shed light on how individuals make decisions, as well as on new technological developments. Leveraging this knowledge, we have developed a comprehensive framework to help healthcare organizations understand the new paradigm and how they can design and implement high-impact, patient-centered interventions.

Elements of the new paradigm

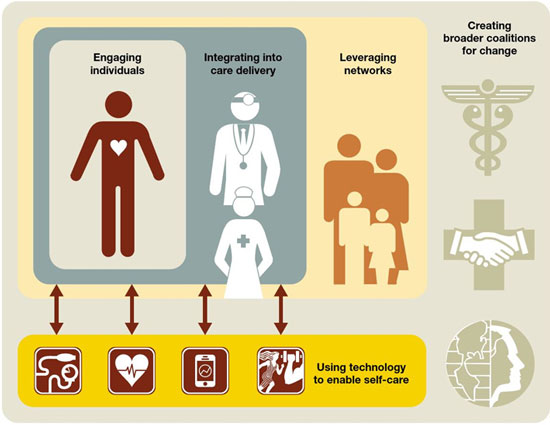

The new model focusing on the individual for behavior change has five key elements:

- The effective engagement of individuals by utilizing new knowledge from behavioral psychology and behavioral economics.

- The integration of behavior change as a core component of new care delivery models.

- The use of the power of “influencers” and (social) networks to promote behavioral change.

- The use of self-care oriented technologies to support individuals and connect them with doctors and other influential people.

- The adoption of a multi-stakeholder approach, which will include public-private partnerships, to support high-impact social and primary prevention interventions.

Commitment of individuals

Knowledge from the behavioral sciences is widely used in financial services, retail, and other sectors to influence what we buy, how we save, and other aspects of our behavior. However, the design of most health-related products, services, and interventions remains remarkably unaffected by these insights into how people make decisions. For example, traditional, clinically guided interventions assume that individuals understand their health-related issues and that they usually act rationally to address them. However, this often deviates significantly from reality.

In a recent survey we conducted, 76% of participants with high-risk clinical conditions described their health as excellent, very good, or good. Programs that fail to take into account this gap between individuals’ actual health status and the way they understand and experience their health on a daily basis (and therefore how willing they are to change their behavior) are “missing the train” from a design perspective. Often, these programs simply attract individuals who are already “activated” to change their behavior, rather than reaching out to those who need help before they can take preventive measures to improve their health.

What does a good design look like? Regarding behavioral change interventions, three innovations seem to be the most important.

Behavioral segmentation should be used to deepen information in specific groups. Current approaches to patient classification and predictive modeling tend to focus on clinical conditions. However, change interventions are more likely to be successful if they take into account additional factors, such as an individual’s behavioral profile or motivation for change. This information allows for more targeted focus on groups of individuals who are more likely to achieve impact. It also enables the design of programs that more effectively address practical barriers to change.

For example, most programs targeting individuals with high hospital admission rates focus on patients through retrospective reports of high-cost episodes based on risk and illness. Incorporating additional behavioral insights allows for a more differentiated approach. In a recent project for a large client in the US, we used demographic data, family status data, and purchasing data to create a “social isolation” index (an index intended to measure the sociability of each individual) for the target population. When combined with the remaining data, this index allowed us to more effectively predict, among groups with equivalent chronic conditions risk, which individuals would be more likely to have a high-cost emergency admission or some other nursing care episode.

We found, for example, that the cost of hospitalization was 24% higher for socially isolated individuals compared to ‘social individuals’ with equivalent levels of clinical risk, and that socially isolated individuals also had lower use of prescribed medications. Such insights can help identify key patient subgroups before high-cost episodes occur, ‘stratifying’ individuals based on specified predictive factors. Interventions targeting these subgroups can then be designed with the appropriate focus (e.g., medication adherence interventions for socially isolated individuals).

Person-focused pathways should be followed to support people trying to change their behavior. Most disease management programs remain rooted in a clinical view of the world. For example, they may correctly identify a patient with diabetes or another chronic condition, but they do not fully address the fact that the same patient may also be overweight, suffer from heart disease, have mild to moderate depression, not trust their doctor, and be socially isolated2.

Clinical knowledge is critical, but our experience shows that program designs are more effective when they directly address the root causes and barriers to behavior change and provide interactions with the right timing and frequency to ensure impact. Essentially, these designs translate clinical knowledge into “individual-focused pathways” that support individuals from the point they decide to make changes until the point where new behaviors are sustained.

A simple example demonstrates the impact of guiding patients to behavior change interventions that best fit their needs. In England, we collaborated with a regional client to improve diabetes care by defining different patient behavior groups and then matching the appropriate support program to each group. General practitioners were trained to identify which group patients belonged to by asking a few simple questions and then to direct them to the behavior change intervention that best met their needs. This simple change led to a ninefold increase in program enrollments (from 7% to 63%) within six months and, most importantly, to a higher program completion rate. Similarly, even very simple defaults, such as automatically mailing orders for prescription refills, can help address patient compliance barriers.

Active communication throughout the journey is also crucial, as frequent feedback encourages behavior change. A study on weight loss that we conducted with leading behavioral economists shows that sending frequent, automated messages (about their progress) helps in weight loss efforts. Written messages are increasingly being used to support patients with diabetes or other chronic conditions, to send educational material, medication reminders, and advice on disease management. The preliminary results are encouraging.

Incentives based on behavior should be used to encourage change. Incentives are an important part of the toolkit for achieving behavior change. Two-thirds of American companies, for example, now offer financial incentives to employees to encourage healthy behaviors.

Well-designed incentive programs have shown results. Discovery’s Vitality program, for example, informs its members about their health status, encourages them to set behavior-dependent health goals, and then rewards them for achieving those goals. Members earn points for behaviors ranging from diabetes monitoring to healthy grocery shopping at supermarkets, and in turn receive various rewards, including movie tickets and discounted flights. Discovery estimates that the program reduced participants’ overall healthcare costs by approximately 15%.

The structure of incentives matters. Incentives that take into account people’s biases (e.g., loss aversion, regret aversion, optimism, and present-biased preferences) are more effective than direct monetary rewards. We recently tested behavior-based incentives using a “regret lottery” design. The goal was to persuade employees of a company to complete a health risk assessment. Half of the workers were given direct cash incentives, while the others were divided into small groups that then entered a lottery. Each week, one group won the lottery, but rewards were distributed only to members of the group who had completed the assessment. Winning groups were widely publicized to leverage anticipated regret (i.e., people’s reluctance to miss out on the chance to win the big prize in the week their group was selected). The result: 69% of workers in the lottery completed their assessments, compared to 43% of those who received direct incentives.

Integration of behavior change into new care delivery models.

Many health systems place increased emphasis on primary care, especially through the use of integrated care delivery models designed to improve population health. To be successful, new models must extend their reach beyond the four walls of a clinician’s office, so they can support patient behavior change beyond traditional clinician-patient interactions. This requires new capabilities, such as clinical assessment tools for targeting patients, care notifications sent to both clinicians and patients, enhanced communication and care management support for patients, and remote monitoring. More fundamentally, clinicians must adopt a patient-centered approach when interacting with patients, one that focuses on understanding the whole person and their barriers to change.

A good example of this type of model is CareMore, a provider from California that focuses on the elderly. One of its main goals is to encourage behavior changes that are vital for the effective management of chronic conditions. CareMore combines technological innovations, such as electronic medical records and remote monitoring, with a wide range of non-traditional services (e.g. caregiver support, preventive podiatry, free transportation to its offices, home visits by doctors and nurses, specially adapted fitness centers, and a team that goes to patients’ homes to investigate non-clinical problems).

CareMore reports that its risk-adjusted cost is 15% lower than the regional average for similar patients and that its clinical outcomes are above average. For example, the amputation rate among diabetic patients with wounds is 78% below the national average, and the rate of hospitalization for end-stage renal disease is 42% below that average.

Using the power of influencers and (social) networks

Health choices do not happen in a vacuum. Our research shows that when people are faced with a health issue, they follow the therapeutic advice of their friends and family 86% of the time. Some efforts to promote health issues have already recognized the importance of these influences. For example, smoking cessation programs for adults in the United Kingdom and elsewhere increasingly target children, because smoking parents are more likely to respond to their children’s concerns than to the prospect of their own ill health.

Those who pay for healthcare expenses and providers have also begun to appreciate the power of influencers in supporting behavior change and have used programs with significant success. In Philadelphia, for example, the VA medical center created a program to encourage better diabetes self-management among African Americans (a group with higher than average diabetes prevalence and significantly increased risk for complications).

The program initially identified “mentors” – other diabetic patients who were already maintaining their glucose levels under good control – and trained them. Subsequently, program participants were assigned mentors with the same demographic background (gender, age, etc.). Participants and mentors interacted on a weekly basis, mostly by phone. After six months, participants had achieved an 11% reduction in their average glucose levels (from 9.8% to 8.7%), a change sufficient to reduce the risk of complications. In contrast, a group of patients who did not have mentors showed no improvement in their glucose levels during the study. Nearly two-thirds of participants said that having a mentor who also had diabetes was important in helping them control their own glucose levels.

As the above program demonstrates, peer-based (social) networks can be relatively easy to implement. Provided that peer matching is done in a way that resonates with participants, these networks can provide an additional support system that will help maintain behavioral change.

Use of remote technologies, focused on self-care

Frequent communication and real-time interaction are very important for supporting behavior change efforts. Traditional care delivery models have at their core face-to-face interactions between clinicians and patients. New technologies, however, enhance this interaction model and fundamentally transform the ways in which clinicians provide—and individuals, friends, and family consume—medical care. Mobile apps, for example, can facilitate monitoring. Wireless devices can transmit information directly from pillboxes, scales, or even “smart pills” that have been ingested. Cameras enable remote consultations. Ultimately, these remote and self-care-oriented technologies can help create a truly interactive healthcare ecosystem.

Many of these new technologies are gaining ground, especially in developing countries, where access remains an issue. However, they are also increasingly used in more developed countries. In the United Kingdom, for example, a large trial of telehealth devices was conducted for patients with social care needs and chronic conditions, which yielded positive results. Participants were given either home monitoring equipment or a decoder that could connect to their televisions. These devices allowed patients to ask questions about their symptoms, provided visual or audio reminders when measurements were due, showed educational videos, and plotted a graphical history of recent clinical measurements. In this trial, the use of telehealth devices appeared to reduce the number of emergency visits and hospital admissions, as well as mortality rates within a year. Several other studies have also shown that telehealth devices reduce the use of healthcare services and that the use of these devices led to savings of up to 13%.

Adopting a multilateral approach

It is becoming increasingly known that if health systems are to address the full spectrum of issues that negatively affect patients’ health, healthcare leaders must collaborate with a broader set of stakeholders to create an environment that will promote guidance toward healthier behaviors and the achievement of results. We have worked closely with clients who are trying to create such broad alliances, which we believe are vital to achieving strong and lasting behavioral changes.

For example, we collaborated with major retailers and food manufacturers in a country to address the rise in obesity by creating a “movement” to raise awareness and encourage consumers, employers, children, communities, and organizations to take action. With the support of a multi-stakeholder alliance, a plan was developed in which the CEOs of participating retailers and food manufacturers committed their organizations to specific goals and actions. These ranged from school health programs, workplace fitness and nutrition programs, and joint manufacturer/retailer initiatives to reduce caloric intake. Although the economic impact and health outcomes of these efforts are difficult to quantify, they are critical for creating an environment that supports more direct interventions. Direct impact can be achieved through appropriately targeted government interventions and public-private partnerships. A classic example is increased taxation on cigarettes, but more creative interventions are also possible. In Argentina, for example, a government-funded program aims to reduce average sodium intake. Thus, bakers were asked to reduce the amount of salt in their bread, but they would be directly compensated for their lost revenue from lower sales.

Impact and Implementation

We believe that the new person-centered model described here is likely to yield stronger results than traditional behavior change programs have produced so far. Disease management programs rooted in the old healthcare model typically achieve savings of 2% to 5% of medical costs. Based on our experience and studies published to date, we estimate that programs designed according to the new model could bring about a 10% to 15% reduction in these costs, combined with greater productivity gains and improved quality of life.

However, the implementation of the new paradigm poses a challenge. A significant issue is scalability: while many of the necessary elements are ready, there are few cases where the entire design is applied at scale. The cost of creating the underlying infrastructure (e.g., platforms for managing incentives and electronic medical record systems) is also an issue – although, in most cases, there are low-tech economic solutions, while continuous innovation simplifies and reduces the cost of many technologies.

The biggest obstacle, however, is the mindset of healthcare leaders and clinical physicians. Most remain rooted in the old model of healthcare. Many are very skeptical about behavior change programs. Some don’t even consider behavior change as part of a health system’s mission. These attitudes hinder the evaluation of behavior change programs based on facts and the adoption of proven successes.

The realignment of health systems around a model focused on prevention, long-term management, and patient-centered care will require leadership and advocacy from the top down. This leadership is necessary if health systems are to address the upcoming wave of challenges in the field of healthcare.

translation/adaptation: Wintermute

- Listen also, regarding the issue of behavior in the new paradigm, to podcast #24 of the red scarves, titled “Behave”, at redscarves.net ↩︎

- Stm: If we are not mistaken, the reverse is true. The clinical picture is exactly this general picture of the symptoms as well as the other parameters of the patient’s condition. ↩︎