A man considered the godfather of artificial intelligence (AI) resigned from his job, warning about the increasing risks due to developments in this field.

Geoffrey Hinton, 75 years old, announced his resignation from Google in a statement to the New York Times, saying that he now regrets his work.

He told the BBC that some of the risks of AI chatbots are “very scary.” “So far, they are not smarter [he means AI systems] than us, as far as I can tell. But I think they will become smarter soon.”

… Dr. Hinton’s pioneering research on neural networks and deep learning paved the way for today’s AI systems, such as ChatGPT.

Hinton’s resignation (although he acknowledged that at 75 it was already time for him to retire…), along with his ominous concerns, caused the international media buzz they deserved in early May 2023—”fortunately not in our village”… His “regret” added melodrama to his dystopian predictions for a near future where our species will be manipulated by artificial intelligence—although such “regrets” are common among specialized computer technicians, and probably free of charge: if they indeed collaborated on something so dangerous, they do not expect posthumous damnation; nor is there a way for them to undo the damage they caused. Therefore, these “regrets” are free, if not theatrical.

Hinton is not the only “big name” expert who is worried. At the same time, millions of people dependent on cyberspace have been fascinated by the capabilities of systems such as ChatGPT, having an unspoken not only childish curiosity (for “what is this new thing that I can approach so easily?”) but also an intense childlike predisposition to admiration for technology. “Childish” does not mean innocent, however…

What is not being said, not even in the margin of fascination or/and dystopian predictions, is how and why artificial intelligence was served so freely on the market of internet communications; so that millions of adult “children” could enjoy it. The Chinese state/capital has been using artificial intelligence applications in recent years for the organization of industrial production, for the organization of mines, for military purposes and for research related to space. These are certainly different types of applications; however, they are not for “mass consumption”.

How then and why did ChatGPT enter so easily into the lives of so many millions of people for purposes that do not appear at first glance to have high “added value”? It is known that Microsoft (owner of ChatGPT) wants to use artificial intelligence as a “search engine” equipment on the internet, in order to hit Google which has almost a monopoly in this sector. The smooth operation of such a system for this use requires the continuous collection of infinite volumes of data from users; the first benefit therefore for the company that will dominate the new market of “navigation” in cyberspace is the more intense profiling of users. The continuously updated individual profiles that will be formed this way will enrich and/or enrich other (similar) databases… Therefore, childish reactions to this specific use feed the digital panopticon.

However, the “cheese” also matters in this specific bean. What is it that suddenly made artificial intelligence so popular? It is that the machine “speaks”, the machine “thinks”, the machine “is smart”. For now, in writing, but soon also orally, with the appropriate (at the user’s/client’s choice) voice color. The concern of people like Hinton about the risks of artificial intelligence’s “intelligence” became possible to socialize through the media precisely because citizens’ “contact” with artificial intelligence has been made in such a way that many have already been convinced of its “intelligence”.

In the previous issue, Separatrix explained the structure of these specific systems, the so-called large language models (LLM)1. He writes in the introduction of his analysis:

…It is almost certain that these systems, which belong to the category of so-called large language models, could successfully pass the infamous Turing test, at least provided that the dialogue would be relatively brief. One issue that arises here concerns how suitable the Turing test actually is for judging the “intelligence” of a system. This is the most “behavioral” aspect of the matter; we deal with how something behaves, regardless of how it arrives at that behavior. Another issue, however, concerns precisely this “how,” the internal operation of these language models that allows them to conduct such realistic dialogues. Beyond whatever autonomy such knowledge of the “inner world” of these models may have, it certainly helps in demystifying them. Offering explanations such as “these are models based on deep neural networks that use transformers” probably doesn’t help much; on the contrary, it might intensify the sense of mystery. To better understand their internal structure, one first needs to take a few steps back…

It would be unlikely for the average user (of the internet) to attribute “intelligence” to such a system if they were standing in front of a screen in a control center of a mine or a port that is completely automated through artificial intelligence applications. A system that would simultaneously and impressively accurately operate excavators in tunnels, loaders and trucks; or cranes, containers, and trucks. In front of something like this, the automations would be blatantly obvious; however, there would be no attribution of “intelligence” to them.

Therefore, in cases such as ChatGPT, even the simplest conversation or observation, obviously childish or not, about machine “intelligence” (always from the perspective of the lay public) is directly related to the Word. The fact that the machine “seems to speak.”

Even if it were a propaganda campaign, even if artificial intelligence in its accessible form to millions, like ChatGPT or any other similar one, appeared in the public sphere to enchant/mislead the public because it “speaks,” this matter is very significant. The mechanization of language can cause childish enthusiasm; but it’s not for children!

Language and the machine

In one of these analyses that seems to have been discovered, if it is to be discovered, probably by future archaeologists rather than by contemporary workers, we wrote among other things:2

… Wiener may have seemed bold in 1950 when he wrote among other things the following; he was, however, accurate as to what was already the desired outcome:

… We usually consider that communication and language are directed from person to person. However, it is equally possible for a person to speak to a machine, as it is for a machine to speak to a person, and for a machine to speak to another machine…

… In a sense, all communication systems end up in machines, but regular language systems end up in only one kind of machine, the familiar human being…

… Human interest in language seems to stem from an innate interest in encoding and decoding…3At this historical moment, in the middle of the 20th century, where the mechanization of communications between “humans and machines” and “machines and machines” has emerged as a new and promising techno-scientific field, and where mechanical language management falls under mechanical communication management (with “information” as the new concept/deity), thought does not seem to constitute an acknowledged goal. Taylor’s (the Taylorist Wiener’s) appears to be a communication-logos.

However, Turing, consistent with the evolution of tailoring into new fields, was less moderate. In a 20-page text of his, from 1950, titled computing machinery and intelligence, he proposes this:

1 – The game of imitation

I propose to consider the question, “Can machines think?” Such an investigation could begin with definitions of the meaning of the words “machine” and “thought.” The definitions should be framed in such a way as to reflect, as far as possible, the common usage of the words; but such an approach would be dangerous. If the meaning of the words “machine” and “thought” is to be found in how they are commonly used, then it will be difficult to avoid the conclusion that the meaning and the answer to the question “Can machines think?” will emerge through a statistical survey, of the Gallup poll variety. But this is absurd. Instead of searching, then, for definitions in such a way, I shall replace the question with another, which is closely related to the first, and can be expressed in relatively clear terms.

The new form of the problem can be described in terms of a game which I call the “imitation game.” It is played with three people, a man (A), a woman (B), and an “interrogator” (C) who may be of either sex.

The interrogator stays in a room apart from the other two. The object of the game for the interrogator is to determine which of the other two is the man and which is the woman. Initially, he knows them as X and Y, and at the end of the game he must make the identification “X is A and Y is B” or “X is B and Y is A.” The interrogator is allowed to ask questions of the following kind:

C: Please tell me the length of your hair.Let us assume that X is A. A’s goal in the game is to try to deceive C, and to push him into a false conclusion. His answer could be:

“My hair is straight and the longest strands are about 10 points long”.

In order for player C not to be assisted by the timbre of the voice, the questions and answers should be written, even better (so that there is no graphic character) on a typewriter…. The purpose of the game for the third player (B) is to assist the interrogator. The best strategy on her part might be to give honest answers. She can even write “I am the woman, don’t listen to him!”, which, however, will not be convincing, since the man (A) will be able to write the same thing.

Now I ask the following question: “What will happen if a machine takes the place of A in this game? Will the interrogator’s final opinion be more wrong in this case than if he played it with two people, man A and woman B?” These are the questions that replace the original, “Can machines think?”

…

This clever shift of the issue of machine thinking, from the anthropocentric Cartesian Cogito, ergo sum (I think, therefore I exist) to the machine-centric Credis me cogitare, ergo cogito (You believe I think, therefore I think), has remained in history (and in practice) as the “Turing test”. However, whether Turing was aware of it or not, it has significant implications. It’s not a game!

The shift made by Turing is pivotal for the issue of artificial intelligence and especially for how it can (or even “should”…) be conceived by the general population.

We could broaden the scope of the imitation game by removing persons A, B, and C from Turing’s setup and placing two African grey parrots instead. This is the most “talkative” species of parrot; it can learn to use 500 or even 1,000 words, making usage choices among them depending on what it hears (or sees) from a human, and furthermore, it can mimic many other sounds, even on command. If someone says “train,” it whistles like a train; if told “nightingale,” it chirps like one. It seems to understand the meaning of the words “train” or “nightingale.” In reality, it distinguishes the sound of each word separately.

It is likely that if two such parrots were together, at some point they would “start a conversation” with each other, which might even produce (human) meaning if they had the same trainer and shared vocabulary repertoire. But it would be a performance…

Think of a well-trained, mature, richly vocabularied African grey parrot; such a thing appears to exist! Whatever-this-such-thing-seems-to-be is certainly what impresses anyone who encounters it; and this is what distinctly differentiates a living, colorful African grey parrot from an ordinary tape recorder.

However, in our own species, humans, there is an increasingly growing misconception – with reasons: that language and thought are identical. Wrong! People who for various reasons cannot or do not want to speak do think (while there are quite a few who chatter without thinking…). A silent person can think. A silent African grey parrot also. An LLM system does not, even if it is fed data.

African gray versus ChatGPT: meaning does not matter

What the LLM programmers did (after a lot of work) was to convert the issue of meaning into a statistical problem. Or, to put it another way, they converted any meaningful sentence, written or spoken, into a record and “copy” of the frequency with which the words of that sentence appear in that particular order in the LLM system’s “electronic file / repository.”

The Separatrix in the text we mentioned earlier writes about LLMs:

…From a purely technical point of view… what matters is that their achievements are based purely on discovering statistical regularities within texts that have already been digitized. When a user asks ChatGPT “to write a story with three paragraphs featuring wizards, dwarves, monsters, and knights,” it successfully responds (perhaps even giving original names to the heroes) because it has already consumed corresponding texts, built up a repertoire of suitable phrases (along with what typically precedes and follows each phrase), and can recall, piece together, and recombine them in various ways.

For this process to be successful (that is, to sound realistic), it obviously requires a massive volume of textual data to train the models and create a sufficient inventory of standardized phrases. This, in turn, implies that bulky … language models are needed—ones that possess the appropriate “capacity” to store multiple combinations of word sequences in order to combine them and produce the sense of originality…

… The neural networks behind language models are the “lords of pastiche.” What they produce is indeed a statistical product, but not exactly random—if by that one means that even a monkey in front of a typewriter might eventually “write” a poem by Borges. Such a model, unlike a monkey randomly hitting keys, will never produce a completely incoherent string of letters (something like “ψλομφ, γγφκπ, οειφμψα”), yet this does not mean that it generates text through “thought.” Its output is produced purely statistically, through textual patchwork. The great realism of their texts stems precisely from their high combinatory ability.

On the other hand, this is also one of their weaknesses. Since they lack any capacity for reasoning, when they make mistakes, these are often monstrous and childlike: the user asks “what is heavier, a kilo of steel or a kilo of cotton?” and the model confidently answers with “arguments” that, of course, a kilo of steel is heavier, because somewhere within the texts it has consumed, steel is always considered heavier than cotton…

(The same mistake would be made by many humans who fail to pay attention to “a kilo” but focus instead on steel and cotton….)

It is extremely doubtful whether a well-educated African grey parrot, with a much smaller repertoire of words or even short sentences, makes statistical correlations when it “responds” to specific questions/auditory stimuli. It certainly does make a correlation, however. Not of meanings; of sounds. From this perspective, it would be fair to consider it smarter (within or outside quotation marks) even than the most perfect LLM system. However, it has no hope of competing with artificial intelligence in any field. Nor, of course, to threaten the human species—even though it can do other things besides talk: it can “bite” your finger hard…

We are dealing, therefore, with “verbal machines,” machines so complex in their construction that they can “play” scrabble with sentences, as long as there is someone opposite them, either a human being or a verbal machine. They always respond, they “answer.” A century ago, if someone came across a door that would open in front of them “by itself,” they would consider that something “magical” was happening. Today we know (even if only in elementary terms…) that electric motion sensors can turn on lights or open a door without anyone touching the handle or the switch. Nothing “magical.” And nothing “smart.”

So why is talk of “intelligence” when it comes to mechanical systems of large language models? Why are they attributed with “intelligence,” even with the addition of the qualifier “artificial,” which does not reduce their “intelligence” as such (an extremely vague concept anyway…), but rather acknowledges their potential for unlimited improvement?

In the end: if there is something genuinely problematic (perhaps even threatening) about “verbal machines,” is it their falsely attributed “intelligence”? Or is it something else?

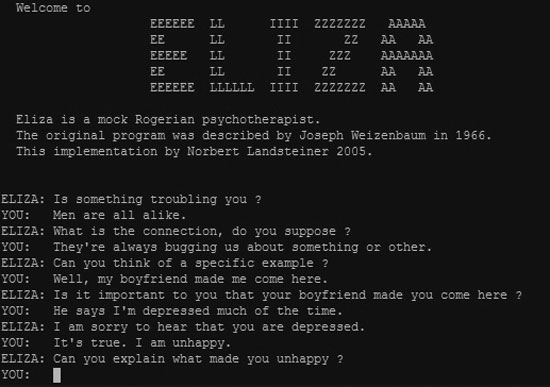

The Eliza effect (the Eliza phenomenon)

B: Is there something that troubles you?

A: All men are the same.

B: What do you think the connection is?

A: They constantly bother us, sometimes about one thing, sometimes about another.

B: Can you think of a specific example?

A: Well, my friend told me to come here.

B: Did your friend tell you something like that?

A: He says that most of the time I am depressed.

B: I’m sorry to hear that you are depressed.

A: It’s true. I don’t enjoy myself.

B: Do you believe that by coming here you will be helped to enjoy yourself?

This little dialogue seems natural, between two people; reasonably, one of them (B) appears to be something like a psychologist. But he isn’t. B is one of the first electronic chatbots, “dialogue applications with machine”… from the distant year of 1966. The MIT programmer who built it (Joseph Weizenbaum) “endowed” the chatbot with psychotherapy verbal data. This means that each and every person who “engaged in conversation” with the Eliza chatbot, as we might say the human part of this “text-based interaction,” was in some way predisposed, convinced that they had some kind of “psychological problem.” Whether to the surprise of Weizenbaum’s team or not, it turned out that Eliza’s “clients” exhibited emotional reactions and attributed human characteristics to the machine. “I had not thought beforehand… that even brief exposure to such a relatively simple computer program would cause strong illusory thinking in quite normal people,” Weizenbaum later observed.

The term “Eliza effect” has since been established as a reference to what was called the tendency to anthropomorphize computers if users judge their “behavior” to resemble human behavior. This “tendency” was subsequently exploited particularly by artificial intelligence engineers: passing (they thought) the famous “Turing test” is rather a matter of successful deception than technical accuracy. Credis me cogitare, ergo cogito…

However, this was a rather selfish to deceitful conclusion. There is, indeed, such a “tendency”; which is inversely proportional to average social knowledge, experience, familiarity with what electronic machines can do “interacting” with their users: many programs of various uses now regularly issue (written) questions to their users regarding the continuation of their actions; but this is considered neither mechanical “intelligence,” nor a hint of “human behavior.”

The “Eliza phenomenon,” that is, the “anthropomorphization” of mechanical functions, was therefore not (nor is it) a kind of innate animism of the human species, although there are indeed cultural conditions and ideas that attribute soul, spirit, or “sacred forces” to everything, even to inanimate objects (and not only to machines); such as Japanese Shintoism.

On the contrary, such an anthropomorphization-of-the-mechanical could be a goal, an ideological (and not only) demand of the owners and manufacturers of such machines. Exactly! That’s what it’s about! This is how it happens from the very beginnings of capitalist development!! Early on in the journey of this very journal, we wrote about it, among other things4:

At the beginning of the 19th century, when the first wave of mechanization (through the establishment of the steam engine) had begun to spread to English textile mills, Andrew Ure, a professor at the University of Glasgow, became famous for publicly supporting the transfer of human thought to iron machines, in order to form a self-propelled mechanism that would grow and learn. Ure, impressed by an automatic spinning machine that had been constructed in 1824 by the engineer and inventor Richard Roberts, celebrated machines endowed with the thought, sense, and attention of an experienced craftsman. Ure named such machines, which he imagined would replace or discipline human labor in textile mills (and in the future in more and more fields), borrowing an ancient Greek word: androids… In Roberts’ spinning machine, Ure saw far more than just a device. He saw the approaching “iron man”: the iron man, emerging from the hands of the modern Prometheus [Roberts], is a creation destined to restore smoothness and peace to the industrial classes and to make Great Britain an empire of technologies.

Not only for Ure but also for the growing number of supporters of the then “new technologies,” in the first half of the 19th century, self-moving machines appeared just as intelligent as the artisans they replaced. The distinction between human and mechanical was overcome; and, since machines were considered as living beings, it would be reasonable for humans to be considered living machines. It seemed that the idea of Descartes, who was chronologically almost two centuries earlier, was becoming reality: Descartes believed that organic bodies are subject to the same physical laws as any other inorganic thing in nature. Of course, Descartes did not completely equate the mechanical with the living and the human: the difference, he argued, is the soul. Initially consistent with what would later be considered a detail, the biologists of the 19th century could attribute all the main characteristics of human activity to essentially mechanical functions, which could be effectively shaped “without a soul.”

What proved beyond any doubt that the union of mechanical/artificial and human is not only desirable but also effective, was the ability (and that of the early 19th century) of artificial limbs for human bodies: wooden legs or iron hooks for arms. Especially wooden legs began to be used more and more due to the also frequent industrial accidents caused by the establishment of new machines, first in textile mills and later elsewhere. These early cyborgs (more accurately: machorgs) became the subject of a somewhat awkward but optimistic advocacy on behalf of Ure: the addition of tools in place of human hands… which is done to help the work of those who are disadvantaged by nature or have suffered some accident, as well as the addition of wooden legs, allows workers to do their job accurately, despite working with the disadvantage of losing a hand or foot.

…The reshaping of the idea of man (essentially of the worker…) based on the specifications of machines also changed the repertoire of discipline within factories. In the first phase, the problem was to make workers and laborers who were peasants—and had a “solar” and “seasonal” sense of time—submit to the clock and to the demand for continuous and intense/concentrated attention to machines. But with the analogy drawn between humans and machines, the issue of human productivity gradually began to transform into a problem of maintaining and better exploiting “human energy.” The objective started to take the form of seeking maximum performance, using the ratio of energy to work per unit of time as the criterion.

…Ure and the other industrialists saw in the spread of the first wave of mechanization what benefited them: the subordination, the attachment of human labor to the machine; the alienation of living labor from the machines. The synthesis was taking place, in their view, both on a small scale (in each individual job) and overall: the factory became the general ideal of the machorg, the model of progress beneficial to employers.

Although in times like the present history is indifferent (when it has not been distorted…), there are important lessons here – (and) for artificial intelligence.

First lesson: the “anthropomorphization of the machine” which these days, regarding “artificial intelligence”, has provided food for research, publications, terminology and doctoral theses for quite a few “experts” in psychology, sociology, etc., is symbiotic with specific capitalist historical periods. Mainly when technologies and applications (i.e. “machines” in the broad sense of the word) that were previously unknown appear in public view or/and use.

Second lesson: the “anthropomorphization of the mechanical” IS NOT the “automatic” reaction of our unspecialized species to each time new machines! There is another reaction that under certain conditions would be the most natural: amazement and the quick, instinctive perception that it is something mechanical! Proof here is how incomprehensible by today’s standards art and mechanical technique automatons were treated in Europe (and later around the same time in China), in the 14th, 15th, and 16th centuries. Automatons that had the form of either animals or humans.

The historical (social, ideological, cultural) “framework” over-determines whether the mechanical imitation of human characteristics will lead to their “anthropomorphization” or not! The makers of those automatons (craftsmen who literally put their eyes out constructing clockwork mechanisms that replicated even the most complex movements…) and their owners (nobles but also the rising merchant/urban class) did not seek through automatons to admonish or forge the image of their subordinates: essentially these masterpieces were out of sight of the masses…

The “certain conditions” are therefore the absence (or/and critique) of capitalist mythology!

Lesson three: the “humanization of the machine” is imposed, promoted, “taught”! In Ure’s time, an era of very limited literacy, this “humanization” was the work of “philosophers”, of intellectuals (of industrialism), with recipients essentially being the upper classes. Not for these classes themselves to feel the danger of being replaced by “iron men”! But to proceed to adopt related constructions in their work – at the expense of the plebs…

However, whether directly or indirectly, this “humanization” – and the 19th century is the all-time manual of it – had as its goal, on one hand, the attribution of human characteristics and qualities (on behalf of the owners of the machines), and on the other, the disciplining of those social subjects who should feel inferior to whatever machines.

Fourth lesson: the abstraction/substitution of human characteristics, or more accurately: the creation of an intellectual/ideological environment that indicates that this or that human characteristic has reduced (social…) value, insofar as it can be replaced by mechanical work, and that this can and should be done “for good purposes”, this process therefore is NOT a side effect of “humanizing-the-mechanical”! It is, on the contrary, its real goal.

Thanks to these historical lessons and through them, we can now judge “artificial intelligence” in a proper way. And first of all: who characterized, named “intelligence” the (electromechanical) statistical classification of anything (in this case words and phrases that have been converted into sequences of 0s and 1s)? And afterwards: why?

The machine matters

It is the legendary Turing who first introduced intelligence as a capability of computing machinery—in the 20-page text we referenced earlier. It is an extraordinary presentation, particularly regarding its predictive acuity, a proof of Turing’s brilliance: he preemptively and systematically addressed all objections to the possibility of “a machine thinking”—in October 1950. Or, at any rate, he addressed all the objections he assumed, imagined, or anticipated would be raised in defense of thought as an exclusively human ability.

At the same time, however, he revealed a stance that could be considered political, if it weren’t for him something far more significant: existential! The machine he had in mind (and note this: in mind!)—a machine that was his theoretical conception, a machine that did not exist at the time he was speaking, a machine whose existence he predicted within 50 years—that digital, computational machine, therefore, was supposed to emulate human thinking; it “had to think”! Which means: to be practically convincing to human beings that it thinks.

We consider characteristic this excerpt from Turing’s thought from computing machinery and intelligence5.

…I will simplify things for the reader by explaining my own beliefs regarding the question “can machines think?”… I believe that in about fifty years it will be possible to program computers with a storage capacity of about 109, so that they can play the imitation game so well that an average interrogator will have no more than a 70% chance of making the correct identification after five minutes of questioning.

The original question “can machines think?” I believe is too meaningless to deserve discussion. Nevertheless, I believe that by the end of the century, the use of words and the generally educated public opinion will have changed so much that someone will be able to speak about machine thinking without provoking reactions. I also believe that there is no utility in hiding beliefs such as this one…

Apart from the evolution of computing machines, it would be the transformation of social perceptions by the end of the 20th century that would confirm that “yes, machines think” – such was Turing’s prediction. The answer would ultimately be given through the overcoming of the question…

But why would a man of such human intelligence claim the capacity for “mechanical intelligence,” fifty years before it was recognized according to his own predictions?

We gave the answer6:

grief and thought

In contrast to his predecessors, who in many respects are considered to belong to the techno-scientific prehistory, Alan Turing is still a legend; the eponymous test, the “Turing test”, continues to be used as a measure of developments in artificial intelligence.

And it was, indeed, intelligence, as an ethical-philosophical question initially, that determined Turing’s path:

…

Alan Turing’s biographer, Andrew Hodges, notes that during his childhood, Turing did not appear to show much interest in what was called “science,” except perhaps a curiosity about chemistry. The turning point was his very intense friendship, at age 16, with his one-year-older schoolmate Christopher Morcom, from 1928 until Morcom’s sudden death in early 1930. Turing loved and admired Morcom for his intelligence, so that after his death, Turing began to feel the tormenting sensation that he should do (and think) what his friend had not had the chance to think and do.

This feeling plunged him into an existential melancholy for three years. As emerges from his correspondence with Christopher’s mother, one of the things that tormented him was the relationship between the human mind, and especially Christopher’s mind, and matter; how thought and logic are materially “recorded”; and how it might be possible for Christopher’s thoughts to be liberated from his physical brain, now that he was dead.

Thoughts and agonies of prolonged mourning—someone might say. Yet these very questions were what drove student Turing into 20th-century physics, particularly into quantum mechanics theory, and into the way this theory addressed the traditional problem of the relationship between mind and matter. First, he plunged into the pages of A. S. Eddington’s book, The Nature of the Physical World. Later, reading von Neumann’s “fresh” work on the logical foundations of quantum mechanics, his emotional state began to find a solid intellectual grounding. The relief offered by the possibility, or even the prospect, of a logical foundation for the relationship between thought and its material inscription or recording, in that same year, 1932, freed Turing also from self-reproach regarding his erotic preferences. From then on, he would come to terms with his homosexuality.

…

Although already known in mathematical circles from his previous work, Turing “changed course” when he presented the “general logic” of a machine’s operation that could perform extremely complex calculations and draw conclusions about anything that could be “translated” into a computational process. His idea was an answer to one of the 23 questions posed to the global mathematical community by the renowned German mathematician Hilbert at the international congress in Paris in 1900, known as the decision problem.

The relationship, the analogy, ultimately the similarity between living thought and dead, with “stored” memory, yet still a productive imitation of it, was for Turing an existential issue that began with his love and admiration for his friend.

We do not “psychologize” the starting point of the idea of attributing intelligence, consciousness, to machines! Rather the opposite: Turing’s categorical assertion that this relationship—an analogy, a similarity—between living thought and its mechanical imitation can and should exist, reaches far beyond technical knowledge and theoretical capabilities. It fits hand-in-glove with the fundamental capitalist function of “substituting” living labor with dead, mechanical labor—conceived as fixed capital, as the boss’s property! Obviously, Turing understood this well: in 1950, the so-called “Cold War” had begun (in our own “measurement”, the 3rd world war), and Turing was already one of the brightest stars in Britain’s techno-scientific establishment.

Despite his iconic position in the history of computers and cybernetics, Turing was not the only one who meant thinking machines. In 1949, the American Edmund Callis Berkeley, a computer engineer, published a 300-page book titled Giant Brains, or Machines that Think… In 1955, the American mathematician John McCarthy proposed (and established) the term artificial intelligence… Ultimately, the use of the term “brain” for the evolving electric computing machines became commonplace because it was promoted (in various ways) “from above.” By technicians, institutions, and the first computer companies.

Long before, then, someone “created” the Eliza effect and long before (with this as a banner…) the anthropomorphization – of – machine was delivered to the general public; long before this “general public” even came into direct contact with machines of such constructive complexity as to mimic, even if only primally, anything that could be conceived as “thought”, anthropomorphization was “constructed” by the technicians themselves and the entire set of propagandistic mechanisms that were in operation from the media of the 20th century onwards!

It is today exactly the same political maneuver as at the outset of the 1st industrial revolution! And with the exact same objective: what George Caffetzis characterized as the armed parade of capital – through the display of its machines and their capabilities7:

…The great industrial exhibitions of 1851 and 1862 were not merely opportunities for intra-capitalist exchanges of information regarding the latest technological developments. These exhibitions were held at London’s Crystal Palace, which meant greater expenses, with the purpose of showcasing machinery to the working class. These exhibitions were a kind of “armed parade,” the purpose of which was to deter enemy attack through a public display of power.

The success of those preventive demonstrations was such that machinery and its power literally became the expression of capital, in general. This was the message that the Crystal Palace exhibitions conveyed from London throughout Europe, and even further, to the streets of Petersburg…

The “armed procession” was not nor is it a one-time event. The “smart machines” of the 19th century media (to the extent they were praised as such) were destined in the following decades to de-skill craftsmen, to transform live labor to one degree or another into “unskilled” operation of machines; and from the moment Taylor succeeded in designing the general restructuring of industrial production at the beginning of the 20th century, the “armed procession” became mechanical possession of manual labor. That is, its devaluation.

Comparable is the purpose of displaying the “intelligence,” the “reasoning” of machines and “artificial intelligence” in the 21st century. The de-specialization of many forms of intellectual labor has been announced. The mass familiarization with the alleged mechanical mind through machines and applications such as ChatGPT aims (once again) to impose the recognition of capital’s superiority: capital, whether in the form of endless datafication and data accumulation, or in the form of their statistical processing, or in any other technical combination, thinks in a superior, flawless, categorical way! The machine is what holds meaning; and here the word “meaning” does not only concern the evaluation of the machine but also everything (every phrase, every image, every sound) to which meaning can be attributed.

We will adopt Turing’s phrase questioning whether “machines can think?” … it is too absurd to warrant discussion – however, without applying the Turing test!! In this arrangement where any machine is revealed only as a form of fixed capital and not at all as an “entity” or “existence” that should be treated as if it were self-existent, the imitation game is not truly a “game” but a political project, a technique of power.

And yes, it is true, there is no need for discussion!!! No, machines CANNOT think; no, there is NO “artificial intelligence” or “machine intelligence”; no, there is no machine “learning” or any other characteristic of life! Any such suggestion to the contrary, any such assurance, any such claim and any such admiration, is a corrosion of the living, aimed at usurpation, alienation and the universal subjugation of life to capitalist dictates! It is a standard-bearer of the “armed procession”! This is, for us, a fundamental principle.

Which, if necessary, can be proven: thought, cognition, intelligence, do not need electric current, batteries, “charging”!! What is called “artificial intelligence” needs…

After this, the African grey parrot stops talking and flies away from the scene towards the unknown…

Ziggy Stardust

- “Artificial Intelligence”: Large language models in the age of “spiritual” enclosures – cyborg 26, February 2023. ↩︎

- The mechanization of thought – notebook for worker use no 3, September 2018. ↩︎

- Cybernetics and society, Papadopoulos edition. ↩︎

- Cyborg 2, spring 2015, The piston, the worker, the boss: anatomy of cyborg ancestors. ↩︎

- Available at https://academic.oup.com/mind/article/LIX/236/433/986238 ↩︎

- Sarajevo no 81, February 2014, The forgiveness of Turing’s sins. ↩︎

- George Caffetzis, Why Machines Do Not Produce Value. ↩︎